“When we encounter something beautiful, we usually experience two kinds of reactions. One may be moved by learning the background of the work or the artist, while the other one is an emotional excitement we feel for no apparent reason.”— Suntory Museum of Art.

One would guess that this quote is based on theories of lateralization, stating that the right hemisphere of the brain controls emotion, while the left hemisphere is dominant in language expression. While there is evidence that discounts the left/right brain concept, many people still believe in this distinction and that their preference for reason or emotion may be genetic.

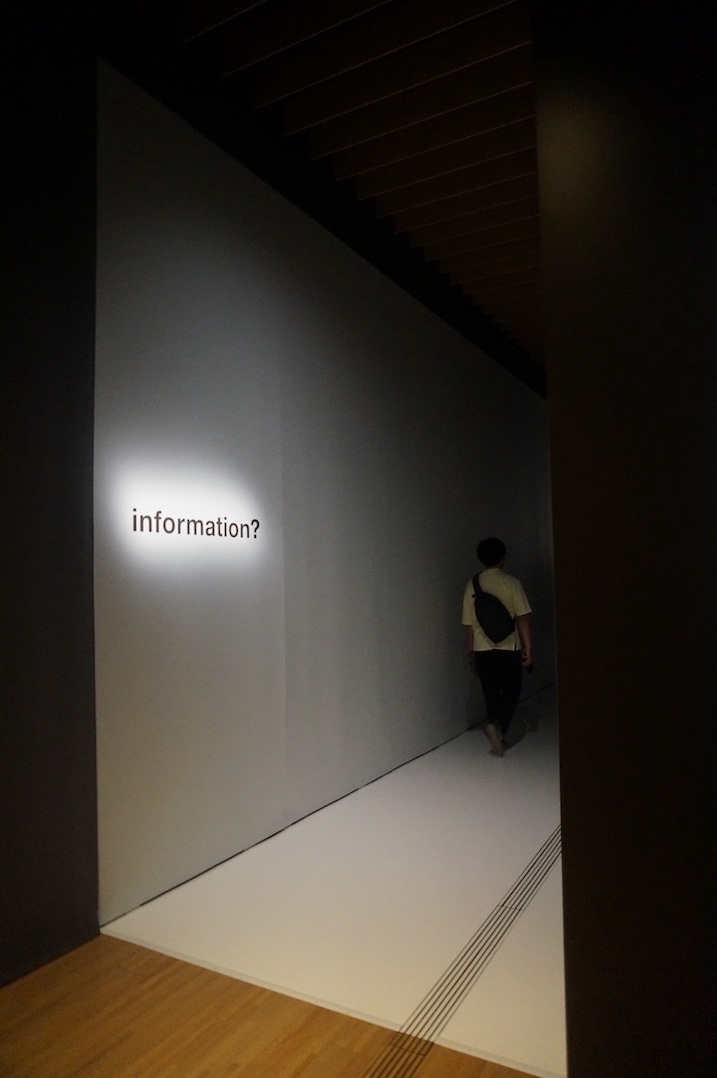

Held at the Suntory Museum of Art in Tokyo, Japan, from April 27 to June 2, 2019, “Information or Inspiration? Japanese aesthetics to enjoy with the left side and right side of the brain” plays with this debate in brain science and invites visitors to experience art via two routes: the information route and the inspiration route.

The exhibition entrance. Photo Credit: Author.

The curatorial team selected 27 items from 300 works of Japanese art and artifacts collected from various places to display in two exhibitions routes (the Information Route and the Inspiration Route), spread out across three different floors in the museum building.

This blog post introduces this exhibition and examines how the interplay between brain science and conventional ways of art display can offer new ways of looking at traditional Japanese design and art. Through this exhibition, I allude to alternative ways of engaging with the museum objects beyond current museological debates around whether visitors should be allowed to “touch” objects, and gesture towards how museums might try to give visitors a more multisensory experience.

I argue that despite its questionable division of the two routes, visitors are able to have diverse experiences when they are given the opportunity to change the way they “look” at things, and that “Information or Inspiration?” is one example of how incorporating knowledge of science and technology with art curation can offer one alternate method in deconstructing museum practice.

Museums and Sensory Experience

It is almost innate to visitors to the contemporary museum that they “know” they should only “look” at objects. “Modern museums have always been known as a space where a feast for the eyes and the eyes only takes place, restraining artworks and artifacts to be presented as purely visual objects” (Chang 2019). Modern Western society (where current structures and models of museums originate) regards vision as the “rational” sensory organ, as compared to other sensorial experiences. Since the Enlightenment, the integration of reason and principle has excluded non-visual, difficult-to-verbalize, unsystematized, and ambiguous elements of body perception. This is especially so in the museum space where “vision” shows dominant power over other senses.

Foucault (1970) has pointed out that behavior in the museum is not intuitive. Visitors are disciplined and regulated by the institution. “No touching rules”, however, do not stop visitors from treating exhibitions as a site for sensory exploration. One of the most prominent features of new museology has been the restoration of touch and advocating the creation of multi-sensory experiences for visitors. The attention given to the sensorium, experience, and bodily engagement in museum studies is evidenced by various scholars (Pye 2007; Chatterjee 2008; Candlin 2010; Levent et al. 2014; Classen 2017).

Current debates on how museums should change their practice and forms of communication have unfolded since the 1990s. One dominant view is that museums should take a more interactional approach and provide the visitors with interactive experiences, and this should be worked into the exhibition design practice (Simon 2010; Falk & Dierking 2013).

Curating Art with Insight from STS

The above context is one reason why museums are taking a more experimental approach, such as incorporating the use of interactive technology in the exhibition halls. The use of augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR) provides an immersive experience for the visitor. In this trend, visitors are allowed and encouraged to enact senses other than vision.

Contrary to conventional art curation teams, curatorial companies like TeamLab[1] are made up of an interdisciplinary group of artists, designers, architects, as well as mathematicians, programmers, engineers, and CG animators.

Many see TeamLab as an example of digital art curation innovation. Compared to an “art museum,” these digital art spaces and projects do not involve artifacts, antiques, or “fine art pieces.” Whether digital art is art is a long and ongoing debate. One of the earliest critiques of mass production of art came from Walter Benjamin (1935), in which he questions the value of mass-culture and argues that the “aura” of a work of art—the authenticity, the uniqueness, and locale are lost even in the most perfect reproduction. This argument sees the “aura” as coming from the “materiality” of artifacts and antiques and as irreplaceable by technological experience.

Despite confrontation with these art critiques, debates across the art world and its relation to technology (STS) are here to stay and are changing both curation and collection practices. As exemplified in the introduction, there is substantial literature that discusses museums in terms of their display of bodies, displays of race, the way they orient the senses, as well the museum profession as scientific knowledge (display / collection science and technology). One way of looking at this, according to Benschop (2009), is to see STS and the different possibilities that it offers to the understanding of art and the arts[2] .

Benschop (ibid: 1) points out that STS “has three areas of interest that make the arts a relevant object of study: (1) STS research into subjectivity and the senses, (2) STS interest in technology and materiality, and (3) STS interest in boundaries between science and other social realms, such as the arts.” The impact of STS on Art is twofold. On the one hand, incorporating STS into the arts changes the way art is categorized and defined, and consequently, new vocabularies are used and developed to describe cases and situations that do not exist before (Becker 1982). One example would be the invention of digital art or computer-generated art. On the other hand, theories borrowed from STS can help deconstruct knowledge systems and knowledge practices in contemporary museum curation processes.

Today there are many exhibitions that look like digital masterpieces, merging art, technology, and science. But there are fewer examples of teams working on curating spaces built around real antiques and artifacts that encourage visitors to reflect on how they “look,” “view,” “imagine,” and ask them to “not reach a conclusion too early.” “Information or Inspiration?” on which I will elaborate in the next section, however, is one such example.

Case Study: Information or Inspiration?

“Information or Inspiration?”, one of the special exhibitions to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Suntory Museum of Art exhibition in Tokyo, Japan, invites visitors to experience art via two routes: the information route and the inspiration route. Along the routes, visitors will see 27 Japanese art pieces or artifacts. The routes use either black or white as the main color for the exhibition halls, combining both the White Cube, the modern gallery and museum space, and the Black Box, the digital and algorithmic space. The White Cube and the Black Box are often used separately in a universal museum to reconsider its relationship to the physical (material) and the virtual (digital) artwork and heritage. This allows the visitor to see the displayed object in a different light.

Visitors are invited to choose to begin with either the Information Route or the Inspiration Route, and regardless of which route they select first, they will return to the beginning/entrance and be able to proceed with the route that they did not initially choose to embark on. One can also choose to only embark on one of the routes.

This “choice” provides the museum with crucial information on how visitors choose to experience art: what do they prefer when looking at traditional Japanese art and why? What kind of information do they need/want to have when looking at the object from different angles? Why do certain people prefer textual information over the actual object, while others are more in favor of viewing the authentic piece and want to experience its “aura”? These are all important questions to understand how the human brain works when encountering “art” as cultural knowledge.

The Information Route route (W: INFORMATION) includes background information of the object, such as materials, production methods, research process, artist’s work, etc. In a more traditional manner of display, the explanatory text and the same pictures are juxtaposed with the objects. Visitors can see clearly the different angles of the object and read a more comprehensive description of it. Information will contain the name of the artwork, the artist, the background of the artifact, the design manuscripts, and other related documents (Image 2).

Satsuma cut-glass boat-shaped bowl with indigo-blue overlay. Late Edo period, Mid 19th century, Suntory Museum of Art. View from W: INFORMATION

Photo Credit: Author

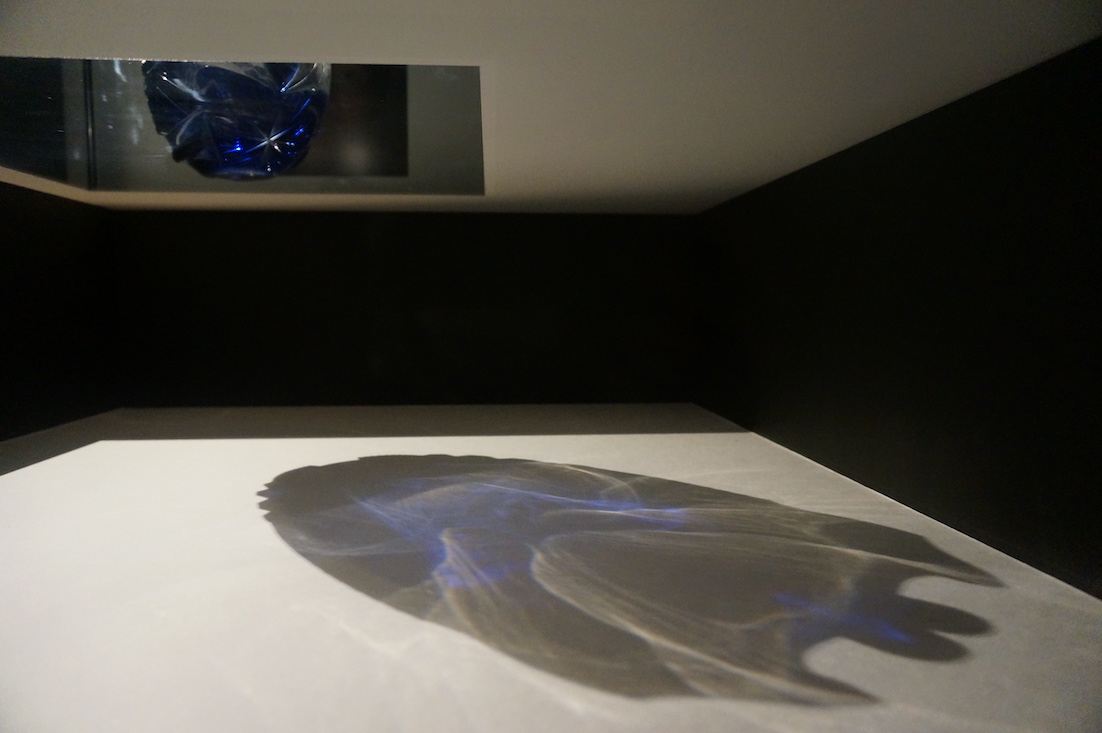

The Inspiration Route (B: INSPIRATION) uses a more obscure display, such as projection, so that visitors can only see the shadow of the object, and the light and color reflected from the projected image. Other display techniques involve hiding a certain portion of the object in the dark, showing only a single facade, shape, or piece of the object. This route is in a black box and so information on the object is limited (such as showing only the date and the artist’s name). Visitors can (and only need to) directly observe and admire the aesthetics of the objects without the obtrusion of preconceived textual information, compared to the Information Route (Image 3).

The same Satsuma cut-glass boat-shaped bowl with indigo-blue overlay. Late Edo period, Mid 19th century, Suntory Museum of Art. View from B: INSPIRATION Photo Credit: Author

Conclusion

I found the exhibition “Information or Inspiration?” particularly suitable to explain how STS, or more specifically the study of brain sciences and aesthetics, might be carried out in a museum.

Firstly, instead of presenting these artifacts in a traditional layout in white walls and glass boxes, this exhibition highlights interactions between artistic outcomes and science and technology. Secondly, this exhibition is experimental, in that artifacts are absent. The entire visit is still highly dependent on the dominant visual senses, but it does not present a full picture of the object or even present the results of the interaction between the object and the external elements and structure within the museum space. To some extent, it challenges both the ways of looking established by traditional museums and also the ways of experiencing introduced by digital art spaces.

Lastly, according to the exhibition manual,

The concept behind the exhibition was not to determine the superiority between the two approaches. It was a conscious decision to separate the experience into two elements to refine their individual values. The recognition that there is an apparent ‘grey zone’ lying between ‘information’ and ‘inspiration’ may be a paradoxical, hidden moral behind the exhibition.

This is not explicitly put forward in the exhibition halls, and it is unclear whether the visitor will arrive at this conclusion or may instead retain a binary view of how they approach art and knowledge in general. The point of departure, building on the debates of the theories of lateralization and questioning them is nonetheless an unconventional new form of curation practice.

For Further Exploration of the Exhibit:

- https://www.suntory.com/sma/exhibition/2019_2/index.html

- https://www.suntory.com/…/exh…/special/2019_2/index.html

- https://www.instagram.com/…/tags/informationorinspiration/

- http://www.nendo.jp/

This post is part of the series “(Re)Assembling Asias through Science.” Read the series’ introduction and contact editors Chunyu Jo Ann Wang (chunyuw@stanford.edu) and Tim Quinn (quinnt@rice.edu) if you are interested in contributing!

[1] TeamLab is a digital art company founded by Toshiyuki Inoko (current CEO) and this friends in Tokyo, Japan in 2001. The company collabs with various artists and teams worldwide. Its works are housed in the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, LA; Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; Amox Rex, Helsinki and many more.

[2] While “the arts” are open to continuous redefinition, it broadly means the creative and imaginative production by humans. The US Congress National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act defined “the arts” as including music, dance, drama, painting and etc. (https://homeweb.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/361_r8.html)

References

Becker, H.S. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California.

Benschop, Ruth. 2009. STS on Art and the Art of STS: An Introduction. Krisis: Journal for Contemporary Philosophy. Issue 1: 1-4.

Candlin, Fiona. 2010. Art, Museums and Touch. Manchester: University of Manchester Press.

Chang, Shih. 2019. “Book Review of The Museum of Senses”. Curator: the Museum Journal, 62(3): 479-481.

Chatterjee, Helen. 2008. Touch in Museums: Policy and Practice in Object Handling. Oxford: Berg.

Classen, Constance. 2017. The Museum of Senses: Experiencing Art and Collections. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. 2013. The Museum Experience Revisited. Routledge.

Foucault, Michel. 1970/2011. The Order of Things. Routledge.

Levent, Nina and Pascual Leone, A. 2014. The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Pye, Elizabeth (ed.). 2007. The Power of Touch: Handling Objects in Museum and Heritage Contexts. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Simon, N. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Museum: 2.0.

Walter, Benjamin. 1935. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” in Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings eds. Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, 3: 1935-1938. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.