This piece is about the unforeseen and sometimes overlooked connection between (i) birds living in the forests of Colombia’s high tropical Andes, (ii) local biologists supporting an anti-mining coalition by conducting an alternative baseline study, and (iii) the undertheorized production of upward vertical territories.

They are entwined around the work of territorial and water defenders in Tolima, Colombia, to disrupt a large-scale gold mining project. During 2018 and 2019, I lived in Tolima, an area in the country’s center that includes elevated humid Andean forests and fertile lowlands irrigated by the Magdalena River. I went to this area to explore how a diverse coalition of anti-large-mining activists stopped Anglo Gold Ashanti Company’s La Colosa project. Since it is a story about a suspended project, the “case” has received varied public and scholarly attention. However, scholars circumscribe “the case” to the pair of consultas populares[1] (popular consultations) that the members of the anti-mining coalition —who call themselves territorial and water defenders— organized in Piedras in 2013 and Cajamarca in 2017. In the two events, approximately 90% of each town’s electorate rejected the La Colosa. The consultas populares are vital to fathom the anti-mining coalition’s functioning and are a kind of collective action “easily” legible as political. However, scholars’ excessive focus on them has downplayed the role of “acts of refusal” that do not look like a “big no” to the mining project. The decade-long articulations between biologists, avian fauna, and anti-mining activists are one of these acts. The connections deeply shaped the process of territorial defense that arose in Tolima, but its story has not been fully told. What emerged from those unexpected links informed biologists’ posterior epistemic production and scientific practice. Those relationships also infused anti-mining activists’ actions with political, legal, scientific, and emotional practices grounded in the idea of an upward verticality to protect the montane forests where the company intended to install the mine.

“Yes to the parrot, not to the gold”

In July 2019, Tolima defenders invited me to go alongside them to Salento to attend a street demonstration against the Anglo Gold Ashanti Company (AGA). Salento and Cajamarca (the municipality where the company intended to establish the open pit mine) were adjacent. Their municipal border is a very high area of the Central Mountain Range (11.500 ft above sea level) in what researchers call the Northwestern Andes. Cajamarca and Salento have similar landscapes: steep slopes covered by many types of tall and medium trees forming dense, foggy, and massive clusters of vegetation that people call either High Tropical Forests or Cloud Forests (Bosques de niebla). A few years before, the Colombian government granted the La Colosa project mining titles over mountainous areas of Cajamarca, Ibagué, and Salento. Due to Cajamarca’s popular consultation results, the titles in this town are questioned. However, the titles in Salento are still valid. This circumstance encouraged Tolima’s anti-mining coalition to expand the geographical scope of their oppositional practices. Defenders used to visit other towns to support actions against the La Colosa mining project.

Photo 1. “Not to the mine” Demonstration in Salento, Colombia. 2019

Photo by the author

As I walked alongside hundreds of demonstrators on Salento’s streets, I paid attention to their banners and chants. From afar, the march seemed like a vibrant line of flapping colors (Photo 1). A white flag displaying the image of a Yellow-eared parrot or Loro orejiamarillo (Ognorhynchus icterotis[2]) stood out among the signs.

Photo 2. Flag of yellow-eared parrot in Salento, Colombia. 2019

Photo by the author

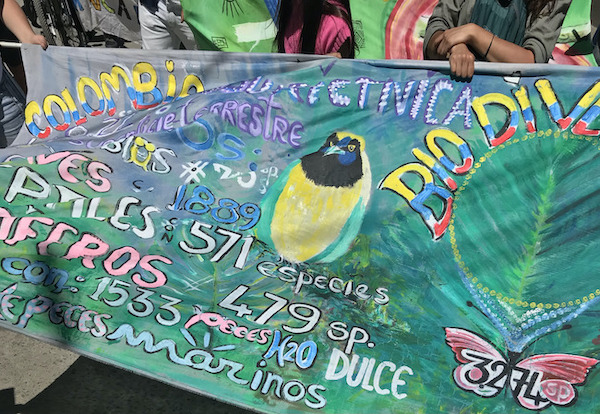

Next to it, a poster (Photo 3) featured a bird, probably an Andean motmot or Barranquero (Momotus aequatorialis), and the word “biodiversity.” Under this term, somebody had written different classes of animals and their number of species in Colombia: “1.889 birds, 571 reptiles, and 3.274 butterflies”. The numbers seemed to substantiate the assertion about the country’s biological diversity, while the butterfly and the bird seemed to embody it. This was not a surprising fact. In Colombia’s history, birds have played an epitomizing role for various purposes. In different moments of the 20th century, politicians and scientists used the country’s bird diversity to fashion sentiments of national identity.

Photo 3. Colombia’s Biodiversity Banner, Salento, Colombia 2019

Photo by the author

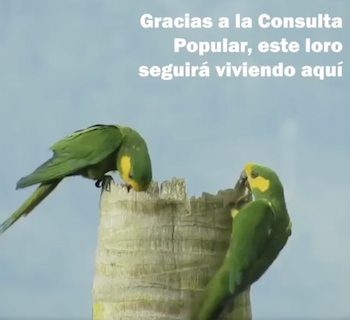

However, when protestors began to chant, “Yes to the parrot, not to the gold!”, which in Spanish is the catchy rhyme “Si al loro, no al oro,” I wondered if, besides biodiversity, birds were indexing something else. I paid attention to the lyrics of the upbeat slogan that activists intoned. It was whimsical and straightforward. It was about the Yellow-eared and other parrots (loros) living in the greenish montane forests that could be seen from Salento, but it was also about gold. Marchers used that term to denote Anglo Gold Ashanti Company’s (AGA) projects in the area. Instead of an enigmatic hostility against a substance, “No to gold” encapsulated the opposition against the La Colosa. This was not the first time I observed images of birds, allusions to them, or even physical avian populations entangled with the language and activities of territorial defenders. In 2021, social media accounts associated with the anti-mining coalitions posted images acknowledging that thanks to the popular consultation, endangered parrots living in Cajamarca’s mountains were protected (Photo 4).

Photo 4. Yellow-eared parrots and Cajamarca’s popular consultation. 2021

Source: Cajamarca La Inconquistable’s Facebook Account

Other organizations that were part of the anti-mining coalition did not use images of the birds but dressed up like them for several demonstrations. In 2019, Roncesvalles Environmental Committee’s young and adult members took the streets wearing parrot costumes.

Photo 4. Roncesvalles Environmental Committee Activity, Tolima. 2019.

Source: Roncesvalles Environmental Committee’s Facebook Account

Three months after Salento’s demonstration, I tried to see the parrots. Alongside my sister and friend, who was employed by the conservation program of the regional environmental agency and was also a human rights defender closely working with Tolima’s anti-mining coalition, we went to the Toche Forest (9.000 ft above sea level) in Cajamarca. This forest is known for its Quindio Wax Palms (Ceroxylon quindiuense – Palma de Cera del Quindío), one of the tallest plants in the high tropical Andes. Yellow-eared parrots live, nest, and rest among these trees. When we started approaching the palm groves to glimpse the birds, my friend told us: “Tolima has the country’s largest amount of wax palms. They are recognized as the national tree because they are beautiful and massive. However, they are also important because Yellow-eared parrots build their nests in the palms’ canopy, and they also eat the palms’ fruit.” Then, turning to my sister as if what he was going to say was too obvious for me, he added, “Do you imagine a gold mine here? We would lose the palms and the parrots.”

These avian encounters raised different questions: How did birds get to be part of the anti-mining coalition? Were these birds simply invoked to uphold claims about regional biological diversity? Which were the roles that montane birds played in territorial defenders’ activities?

How did birds get to be part of the anti-mining coalition? The alternative baseline and biologists’ vertical attunements

In 2019, the Anglo Gold Ashanti Company conducted a preliminary environmental baseline to request exploration permits for the La Colosa project in Cajamarca. The corporation conducted the study because it was a requirement to operate inside the Central Forest Reserve, an elevated protected forest area in Cajamarca. Baselines and EIAs’ primary purpose is arranging and presenting scientific advice in contexts where multiple forms of natural resources management coexist. Baselines should describe the environment of the area where the project will operate, which means that they “create a framework for environmental comparison,” ultimately “making a landscape legible for human use” (Barandiaran, 2020). Baselines are highly contentious. They could be a source of disagreement in the middle of disputes triggered by mining and infrastructure projects. If the reference point displayed by the report is inaccurate, the baseline, as affected communities and environmental advocates argue, will obscure rather than illuminate the ecological impacts of the industrial resource extraction (Barandiaran, 2018, 2020; Barandiaran & Rubiano, 2019).

Not surprisingly, AGA’s baseline document created controversy among the anti-mining coalition. When a group of local biologists, who had started an alliance with the coalition, read the report, they noticed that the number of animal species registered in the baseline report was very low for the area. Ana, one of the biologists, told me during our interviews: “that the number of birds [in the company’s report] was especially misleading.” Small farmers in Cajamarca also rejected the report invoking this and other arguments. Ana and other life sciences professionals further claimed that the Anglo Gold Ashanti Company’s efforts to conceal the number of species in the project’s area of influence served the purpose of obscuring the mine’s long-term impacts. However, this assertion was difficult to prove. To demonstrate it, anti-mining activists in Cajamarca and biologists in Ibagué started to work together, thus consolidating the type of coalitional politics that characterizes Tolima’s process of territorial defense. After a few meetings weighing the best course of action, biologists and local organizations agreed on a more formal response to AGA’s baseline report.

In February 2010, in Conciencia Campesina’s blog, Marco, another biologist, authored a text explaining the upcoming initiatives they would undertake. Under the title of “Cajamarca, our biodiverse heritage,” he announced the creation of a group of researchers who would contest the company’s environmental study. Next year, in 2011, Ana, Marco, and nine additional researchers conducted an “in-solidarity” environmental baseline for Tolima’s anti-mining coalition to refute AGA’s first environmental baseline. The research team chose three sites in Cajamarca to conduct the alternative baseline report. Located inside or very close to the La Colosa project, the spots were examples of high tropical forests. The fieldwork was nerve-racking for researchers and their small-farmers companions because armed men in motorcycles regularly followed them. The guards wanted to prevent the team from collecting data and samples. However, small farmers came up with a solution to the impasse. Instead of roaming inside the La Colosa’s zone, the team would collect samples and conduct observations in the immediately adjacent plots over the borders. Thus, the study would be technically conducted in “the same area,” but without the risk of wandering inside the mining project’s perimeter.

The team monitored animals’ activities day and night, recorded in audio and visual formats, and collected insect and bird samples. Following the recommendations of small farmers who were members of the anti-mining coalition, they interviewed local dwellers to further understand the area’s biodiversity. Marco and Ana explained that birds got special attention because “they were the taxonomic group that was most problematically underrepresented in AGA’s baseline report.” The company’s study only registered thirty species of birds. The omission of well known and critically endangered birds, such as the Indigo-winged parrot (Hapalopsittaca fuertesi – Lorito de Fuertes), made the study’s avian component a crucial element. Montane birds are silent, elusive, or difficult-to-be-seen. To address those issues, researchers used “intensive search and audio recordings playback” and eight diurnal mist nets for nine days[3]. To include in the alternative report “those birds that use the forest’s upper layers” and therefore evade the mist nests, researchers carried out visual censuses aided by binoculars from 2:00 pm to 6:00 pm.

High Andean tropical forests are humid due to precipitation but also because they attract cloud belts that bring water in the form of a “fog drip.” In a montane or cloud forest, the conventional forest layers are not easy to identify since there are trees of very different heights. Thus, the inclusion of birds living in the canopy (upper layer of the forests) and the emergent layers result from the team’s techniques and researchers’ embodied dispositions to the area and its different elevations. As biologists expected, the results of the alternative study were different. Unlike AGA’s baseline, which reported 30 bird species, Ana and Marco’s group registered 157 species of birds in the La Colosa area. In his master thesis, Marco wrote: “It is clear for us that the AGA’s report does not account for the total of 224 species of birds (17 orders and 40 families) that have been reported for the area of influence of the La Colosa project.” Furthermore, “according to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), in the area, there are six “threatened” species of birds and not two like the company’s initial report registered.” After biologists conducted the alternative baseline, anti-mining advocates began to draw upon this research’s results to inform and strengthen their arguments against the La Colosa mining project.

Were these birds simply invoked to uphold claims about regional biological diversity?

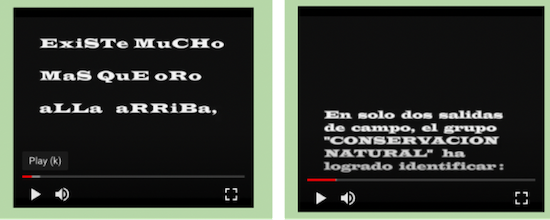

After biologists and Cajamarca’s small farmers publicly shared the alternative baseline’s results, anti-mining activists began to rely heavily on imageries about the mountain and the birds to explain their claims of territorial defense. For example, under the title “Starting to walk” (Empezando a caminar), a blog entry in which members of Consciencia Campesina reflect on the type of political actions they were doing, the organization included a rough-and-ready video mentioning how the mountain’s most elevated areas have been disregarded or not fully understood (Photo 5).

Photo 5. “Empezando a caminar” (Starting to walk). 2011 Source: Conciencia Campesina’s Blog

The first image of Photo 5 shows the message: “there are much more things than gold up there [Cajamarca’s mountains].” The second introduces the alternative baseline and findings, underscoring the large bird diversity the researchers disclosed: “in only two field trips, the research team identified more than one hundred species of birds.” This information is followed by approximately twenty photographs of montane birds taken by a forestry technician who participated in the alternative baseline. These images encapsulate and illustrate a central argument of the coalition: the mountain was unique due to its different species and was endangered by a potential large-scale mine.

In his study of environmental politics in Hong Kong, anthropologist Tim Choy explains that the fabrication of endangerment as a fact entails idioms of exceptionality, inscription devices, and different types of alliances. He argues that uniqueness results from practices of specification, which he defines as procedures to establish that animals in an area are not the same ones living in other (Choy, 2011). Drawing upon and expanding Choy’s ideas, I argue that in Tolima, members of the anti-mining coalition fashioned the mountain’s uniqueness by rendering politically and legally visible life forms with highland specificities. That is, animals or plants with the quality of relating distinctively to Tolima’s montane forests. Mobilizing and amplifying the information collected by biologists, activists emphasized that the region’s bird diversity results from its different altitudinal gradients. To make Cajamarca’s mountainous areas —which they simply call “the mountain” (la montaña)— a shared object of interest, anti-mining advocates heavily relied upon making visible and intelligible the mountain’s above-the-ground verticality.

Which were the roles that montane birds played in territorial defenders’ activities?

Tolima territorial defenders have given special prominence to birds to highlight the uniqueness of Cajamarca’s mountainous areas. In public hearings with state officials, research activities, street demonstrations, and audiovisual products, anti-mining advocates brought montane birds’ distinctiveness to the fore of their struggles to demonstrate that the mine’s impacts extend beyond the underground and earth’s surface. By organizing monitoring activities, making videos and posters about birds, and even dressing up like parrots and hummingbirds for rallies, activists connected their struggles and the protection of montane birds. These public articulations further consolidated defenders’ claim that large-scale gold mining affects the territory’s above-the-ground vertical dimension, not only its underground verticality.

To oppose mining authorization requests, activists underscored the potential mine’s long-term environmental impacts: the disappearance of the mountain and its “exceptional animal,” plant, and fungal species. They politically produced the mountain (la montaña) as a multispecies entanglement with unique social and ecological values.

Contributions beyond the case

Birds and mountains made me reflect on the renovated attention to geological studies in social sciences and, particularly, the concept of verticality. Many of these works suggest that space should be tackled as a volumetric realm, not a two-dimensional surface. These studies have demonstrated that geological knowledge and diverse artifacts, such as maps, surveys, diagrams, samples, and 3D data visualization tools, enable the visibility and legibility of landscapes in vertical axes (Braun, 2000). That is, these devices played a fundamental role in the vertical production of the space. Most of these works focus their vertical framework on the production of the underground as a commodity and an object of knowledge, intervention, and government (Marston & Himley, 2021). However, emphasizing what happens below the surface could leave undertheorized the above-the-surface vertical production of space. The second contribution goes along the same lines. Although recent studies explore the links between multispecies entanglements and the production of space and nature, not so many works are examining how animals and plants contribute to the volumetric intelligibility (production) of space and nature. This is especially true for sites disputed and, therefore, reconfigured amidst environmental struggles and produced as multispecies entanglements for territorial defense.

Notes

[1] Consultas populares are similar to referendums but not the same. Originated in the 1991 constitution, they are a type of legal-political technology oriented to guarantee citizens’ right to political participation. Tolima’s defenders deployed these legal tools to prevent La Colosa’s establishment.

[2] All birds’ names are presented in their English common names, followed by both the Scientific name and the Spanish common name.

[3] This technique is oriented to capture individuals but not necessarily to kill them.

References

Barandiaran, J. (2018). Science and Environment in Chile: The Politics of Expert Advice in a Neoliberal Democracy. The MIT Press

Barandiaran, J. (2020). Documenting rubble to shift baselines: Environmental assessments and damaged glaciers in Chile. Nature and Space E, 3(1), 58–75

Barandiaran, J., & Rubiano, S. (2019). An empirical study of EIA litigation involving energy facilities in Chile and Colombia. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 79, 1–10

Braun, B. (2000). Producing Vertical Territory: Geology and Governmentality in Late Victorian Canada. Ecumene, 7(1), 9–46

Marston, A., & Himley, M. (2021). Earth politics: Territory and the subterranean – Introduction to the special issue. Political Geography, 88, 102407