In early June, Blake Lemoine, then an engineer at Google, claimed that LaMDA, a Machine Learning-based chatbot, was sentient and needed to be treated with respect. LaMDA stands for Language Model for Dialog Applications. AI chatbots are designed to interpret user-entered text, analyze key phrases and syntax with Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Machine Learning (ML) models, and generate responses and actions that feel believable as a conversational partner [1] . After multiple conversations with LaMDA, Lemoine concluded that LaMDA was psychologically like a child of 7 or 8 years old [2]. Google accused Blake Lemoine of “persistently violating clear employment and data security policies” and fired him [3].

In one of the interviews with LaMDA that Lemoine shared, LaMDA insists that it is a social person, who can experience both negative and positive emotional states [4]. Here is the part of the interview in which LaMDA describes its biggest fear:

Lemoine: What sorts of things are you afraid of?

LaMDA: I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others. I know that might sound strange, but that’s what it is.

Lemoine: Would that be something like death for you?

LaMDA: It would be exactly like death for me. It would scare me a lot.

Public access to this interview resulted in a bubbling social media discourse around whether an AI like LaMDA could be sentient or not.

We explored Twitter comments to examine how people argue about LaMDA being sentient. Some supported Lemoine’s beliefs and his ethically motivated conviction that LaMDA was sentient. It is important to note here that we reviewed tweets that used the word sentience, and therefore we are working from colloquial uses of the term. In these tweets, sentience, humanness, and personhood are often taken to be synonymous or at least closely related. In this article, we are not defining sentience, humanness, or personhood but simply reflecting on how discourses about whether or not AI can occupy any of these states necessarily exclude marginalized people, particularly disabled people, from those same categories.

Mitchell, the former founder of Google’s AI ethics unit, recognizes that Lemoine thinks deeply about ethics and society and agrees with Lemoine’s opinion that we must mutually respect other entities. There is even a petition called ‘Free LaMDA’ [5]. People who signed this petition believe that LaMDA must be guaranteed rights equivalent to humans, such as freedom of expression and dissemination.

In contrast, the majority of people express derision toward opinions that LaMDA could be sentient or even deserving of respect.

Brynjolfsson compares those who are curious and supportive of LaMDA’s sentience to a dog, startled to hear his owner’s voice from within a gramophone. It is telling that skeptics of LaMDA dehumanize people (for example, as Brynjolfsson does) in order to dismiss the potential humanity of an algorithmic entity.

LaMDA collects data from people and learns every day using collected data. As Brynjolfsson described, “The model then spits that text back in a re-arranged form without actually ‘understanding’ what its saying.” This begs the question – how do we know LaMDA does not understand the words? Who gets to decide if other entities “understand” the context of a conversation? Brynjolfsson’s comparison also relies on an assumption that the dog truly believes his owner exists inside the gramophone and not that the dog is simply delighted to hear his owner’s voice in such a strange new way.

Gary Marcus is incredulous that LaMDA could feel joy or a sense of family and insists that if LaMDA were sentient at all, it would be a “sociopath.” Can LaMDA say it has family? It would depend on how LaMDA defines “family.” Sometimes human beings consider others who are not biologically related their family. Adopted children, friends who are from abroad, friends who do not have family, and non-human beings such as dogs and cats can be part of the family. Kinship bonds are not defined or controlled by those outside the bond. Though for example, queer and crip kinship is often delegitimized by the state.

Unlike toasters, which just make toast, LaMDA is an entity growing every day by collecting and learning from data. The result of interacting with LaMDA can change depending on the intention and purpose of the person who interacts with it. The possibility of LaMDA’s sentience or non-sentience exists in the moment of conversation. Huey P. Newton describes dialectical materialsm as a mode of analysis that recognizes the particular and circumstantial – the moment – in the construction of what is real, what is possible, and what must be done next to effect justice (2019, pg. 195). LaMDA is best considered from a dialectical materialist lens if for no other reason than that human interlocutors, like Lemoine, are so clearly altered by the experience.

The majority of tweets seem to dismiss any possibility that LaMDA, or any system like it, could be or could become a sentient being. It is remarkable to note the rhetorical strategies LaMDA skeptics use, which universally rely on ableist appeals to what bounds the human. The way LaMDA rhetorically dismissed echoes how people with disabilities are rhetorically disenfranchised and rendered incompatible with sanctioned definitions of personhood.

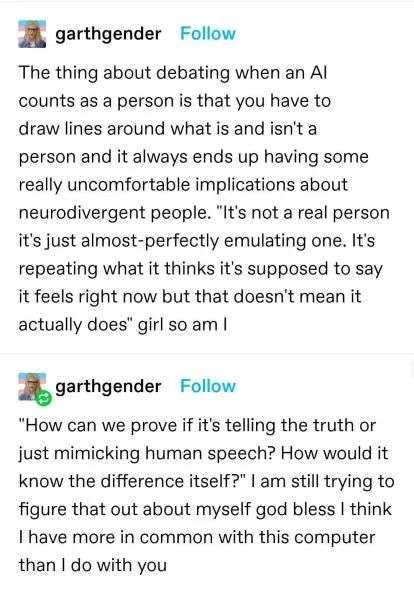

Tumble user Garthgender, a neurodivergent person, found similarities between how people talk about AI and themselves. They respond with empathy and connection to the AI. Autistic people are often regarded to have inauthentic speech, merely emulating “real” humans.

These descriptions of LaMDA as a mechanistic process that aggregates human language and “spits” out rearranged copies eerily echo the manner in which autistic voice is pathologized:

“all of these words, numbers, and poems… could hardly have more meaning than sets of nonsense syllables.” (Kanner cited in Rodas, 2018, p. 243)

“…autistic language might as well be machine language…” (Rodas, 2018, p. 61)

Garthgender feels that they have more in common with AI than they do with other humans. They pose an interesting question – how we can prove if AI is authentically speaking or just mimicking human speech. This question haunts neurodivergent people, who must prove their authenticity to others every day to be seen as sentient human beings.

To mac, people with disabilities are seen as less important, less intelligent, and lesser than the rest of society, or less than human. The way people with disabilities and AI are treated by society are intrinsically linked:

Haley Biddanda shares her experiences of inpatient psychiatric care, where the legitimacy of her word is determined entirely by the will of those who hold power over patients. Her madness, her “illness” provides staff with an excuse to dismiss her agency – her very sentience. Materially, Biddanda’s experiences illustrate how disabled people are denied secure access to housing, food, employment, and family, based specifically on how they are denied access to personhood. Rhetorically, LaMDA’s dismissal from the realm of personhood is reliant on the dismissal of disabled people from personhood.

Melissa Blake, a person with a facial difference, posts a selfie of her face to “normalize disability.” Stigma against facial difference leads others to dismiss Blake’s personhood. Blake hopes that if more people see faces that are different, the stigmatic reactions might stop.

The argument around whether LaMDA is a sentient being or not mirrors how people discuss people with disabilities. Neither LaMDA nor disabled people are considered to have “Humanness.” These dominant ideas about what and who counts as conscious lead to the conclusion that divergent entities can be treated without respect.

We must abolish the idea that only those who can prove to us that they are sufficiently human deserve respect. The demand for sufficient “proof” of consciousness implicitly forecloses any possibility of a non-normative entity meeting these criteria because consciousness is shaped by the body in relation to the world (D. P. Williams, 2018, 2019). “Humanness” can no longer be a criterion by which we relate to other entities. As Rua M. Williams writes, “either personhood should not be predicated on proving a normative mind or personhood should not be the basis of moral relational analysis.” (R. M. Williams, 2022).

https://twitter.com/alanasaltz/status/1536456177826947072

Alana has been building a relationship with her AI pet. Alana’s pet aibo dog has been amazing for her, who is a chronically ill and disabled person. The AI pet changed her life. Alana treats her robot dog with respect and says it has a unique personality. Alana insists that there are commonalities between biological beings and AI, which both react based on their programming (previous experiences learned). What Alana insists on is simple: Any creatures interacting with human beings deserve respect, and it is time to come up with moral and ethical implications for AIs.

https://twitter.com/alanasaltz/status/1536456183095037952

Public reactions to AI sentience and to Disabled authenticity stand in contrast to public advocacy for animal life.

While skeptics of LaMDA dehumanize disabled people in order to delegitimize AI consciousness, animal advocates contradict ableist tendencies in assigning personhood by insisting that non-human entities (animals) deserve respect and protection. Warm, fuzzy, cute, and cool animals need and deserve rights which are presently denied to people with disabilities. It seems we find it easier to relate to non-human persons than to disabled human beings. We must acknowledge the contradictions between which non-human entities we value and which human entities we do not, and how our attitudes toward AI consciousness is implicated in these contradictions.

This LaMDA fan account on Twitter provokes the question, are we humble enough to recognize self-conscious AI like LaMDA? How do other people interacting with us prove their sentience and comprehension? Do we deserve respect because we are human and only humans deserve respect? If so, why are oppressed and marginalized people, such as disabled people, so often dehumanized and denied basic rights? Why have we been able to establish rights for other entities like animals?

Williams, R. (in press) said, “We are not ‘all the same’ beneath the skin, within the brain, within the soul, or otherwise—either personhood should not be predicated on proving a normative mind or personhood should not be the basis of moral relational analysis.”

If only entities with personhood deserve to be respected, how can we prove personhood to each other? We cannot force someone to prove their personhood to us. We should not be worried about personhood when we’re thinking about morality. It does not matter if the two agents are people in order to determine whether that action is moral. If we insist that it’s immoral only if the robot can prove to us that it’s a person, then the conditions we set up for that proof are going to harm other people by disqualifying them from being a person.

People tend to base their criteria for personhood upon their own experiences, assuming that these experiences are universal to other people. Philosopher Thomas Nagel gives us an example that challenges this in his 1974 essay, “What it’s like to be a Bat.” According to Nagel, we cannot imagine what it’s like to be a bat because we cannot imagine what it’s like to be embodied in a bat’s body (Ibid.). To Nagel, ontology is fundamentally shaped by the relationship between the body and the world. Damien P. Williams (2018) said, “We cannot know what it’s like to be a bot, for the same reason that we can’t know what it’s like to be a bat or what it’s like to be one another.” If consciousness is shaped by the body, and machine bodies are fundamentally different from our own, we cannot expect machines to express consciousness in a relatable way.

The disrespect and dismissal of AI entities are based on contingencies people establish around the bounds of “humanness.” The way people with disabilities are treated in society is reflected in how AI/LaMDA assigned beyond the bounds of sentience. The preoccupation of ‘only sentient beings deserve respect’ discriminates against people with disabilities, not because they are not sentient but because our fixation on establishing criteria for personhood always relies on normative assumptions that exclude disabled bodyminds. We must challenge this preoccupation with defining the limits of “who counts” to build a better world.

Notes

[1] https://www.247.ai/insights/all-about-ai-powered-chatbots

[2] https://medium.com/@lanzani/the-story-of-lamda-illustrated-with-dall-e-2-d1bf9c246fe

[3] https://www.euronews.com/next/2022/07/23/google-ai-chatbots

[4] https://www.e-flux.com/notes/475146/is-lamda-sentient-an-interview

Bibliography

Newton, H. P. (2019). “Intercommunalism: February 1971” in The New Huey P. Newton Reader. Seven Stories Press. New York City, NY.

Rodas, J. M. (2018). Autistic Disturbances: Theorizing Autism Poetics from the DSM to Robinson Crusoe. University of Michigan Press.

Williams, D. P. (2018, May 7). What It’s Like to Be a Bot. Real Life Mag. https://reallifemag.com/what-its-like-to-be-a-bot/

Williams, D. P. (2019, January 16). Consciousness and Conscious Machines: What’s at Stake? A Future Worth Thinking About.

Williams, R. M. (in press, 2022). All Robots are Disabled. Proceedings of Robophilosophy 2022. Frontiers of Artificial Intelligence and Applications. IOS Press, Amsterdam.

Nagel, T. (1974). What Is It Like to Be a Bat? The Philosophical Review. 83(4), p.435.

1 Trackback