Introduction

When seen through the experiences and histories of experimentation and care, plants such as roses can bring new insights into the affective and material entanglements of more-than-human relations. My ethnographic encounter with Mr. Changa, a prominent figure in the world of horticulture and plant nurseries in Pakistan, gives us a glimpse on “seeing and being-with” (Haraway 1998) non-human others, such as roses, to foreground the making of social worlds through affect. These encounters show that even though colonial inscriptions on social understandings of nature were marked in influences over tastes and attitudes (Mintz 1985), an attention to nuanced affects, articulations, and values can disrupt the process of creating “authentic” relations with plants and singular legacies of expertise. Writing against the dominance of an object-oriented ontology in mainstream science and technology narratives, this post follows scholarship that emphasizes an “anthropology beyond the human” (Kohn 2013) to center the connections between plants and humans as not only metaphorical but literal (De La Cadena 2010).

“Mujhe gulab se ishq hai” (I am in love with the rose)

One of the varieties Mr. Changa cultivates is the Moonberry Rose that has a distinctive pink shade. While color, scent, texture, petal shapes, and stem features are some of the ways to distinguish the flowers, rose growers will also identify soil conditions, water quality, and climatic conditions as forms of care. Photo by Author.

When I entered the plant nursery, I saw an elderly man fervently engaged in talking to customers and meting out instructions to other assistants. Rows of ornamental trees, house plants, and various seasonal flowers were arranged in an eye-catching manner. The nursery was buzzing with activity. I was surprised to learn that some of the customers had traveled from as far as Karachi, more than seven hundred miles away, to Pattoki. The city is the hub of wholesale trading for plants in Pakistan, as well as home to more than a hundred private nurseries. While Pattoki is known as the “City of Flowers,” the Changa Nursery is famous for the most coveted flower, the rose. As Mr. Changa declared enthusiastically, “Yahan aam, shatoot ki nurseries tau baht thee’ magar mein pehlay din se gulab pe latoo tha (There were plenty of nurseries selling mango trees and Mulberry, but I was enamored by the rose from day one).”

As we sat down next to his personal rose garden to talk about the history of Pattoki and his work with roses, Mr. Changa was no longer holding a pen and sales slips. Instead, he had brought out some of his favorite books to show us the techniques and climatic zones for cultivating different varieties of roses. The first edition of David Austin’s English Rose, a sacred text for any serious rose grower according to Mr. Changa, was a cherished companion among his extensive collection of books. This book documented the journey of British horticulturalist David Austin who set a world standard for rose cultivation when he successfully created the English rose in 1969.[1] Mr. Changa’s admiration for David Austin’s devotion to the craft and care of roses was not a complacency with colonial systems of knowledge but rather the wonder of experimentation joined with care for the roses he was growing. As Archambault (2016) has proposed, affective encounters occur when “a meeting with someone or with something” can produce “some sort of effect; when it inspires, unsettles, troubles, moves, arouses, motivates, and/or impresses” (249). It was in the same state that Mr. Changa went over descriptions in the book. He took me through marked pages in his collection to show the process and types of pavandkari (grafting) and the potential results on the color, texture, and form of the rose plants.

Without any formal education in horticulture or botany, Mr. Changa’s journey on experiencing plants came from his schooling in the village. It was there that he learned of different planting practices and different types of soil such as the bhal mitti (clay soil), halki mitti (light soil), raet mitti (loamy soil), and khaalis raet (pure sand). He grew up as a farmer’s son in the fertile Indus plains and even as he marked a different path as a nursery business owner, he found that his roots in Pattoki could not be disengaged from his passion for roses.

Grafting is a botanical technique to cross-fertilize different varieties of plants. This allows for plants to evolve their apparent physical qualities as well as non-visible characteristics, such as resistance to disease. Grafting experiments have brought about new varieties of plants and extended plant networks all over the world. Photo by Author.

At the same time, Pattoki’s development as the hub of nurseries is entwined with a historical, political, and capitalist construction on the place of nature. The city is situated next to colonial-era railway tracks and postcolonial road infrastructure that expanded the possibilities of intra-country trade and promotion of Mr. Changa’s roses. Pattoki’s ability to physically sustain such a large number of nurseries and plant farms also comes from its proximity to Punjab’s rivers and the fertile Indus plain. Furthermore, the soil that nourished the roses came from riverbeds, mixed with ganay ki mael (sugarcane leftovers) and rice ash, from the adjoining agricultural fields. However, while the urban sprawl raises concerns on the availability of these agricultural residues and soil health, it has spurred the demand and circulation of nursery-grown plants and flowers. The Changa Nursery Farms “Rose Specialist” is one example of businesses that have taken to social media platforms to expand the potential and circulation of their roses and plants. In these transformative mediations, the roses’ beauty comes to be prized through its grower’s reputation and fame.

“Sonay se bhi Zaida” (More than gold)

Of the over two hundred hybrid varieties produced under his care and supervision, Mr. Changa had named several of them after prominent national figures or events. At the rose farm, he took us through several different ones. “This one is ‘Our Allama Iqbal’… this one is August 14… this one is Dr. Iqbal,” Mr Changa explained as he gently cupped the roses by holding them from the bottom center.

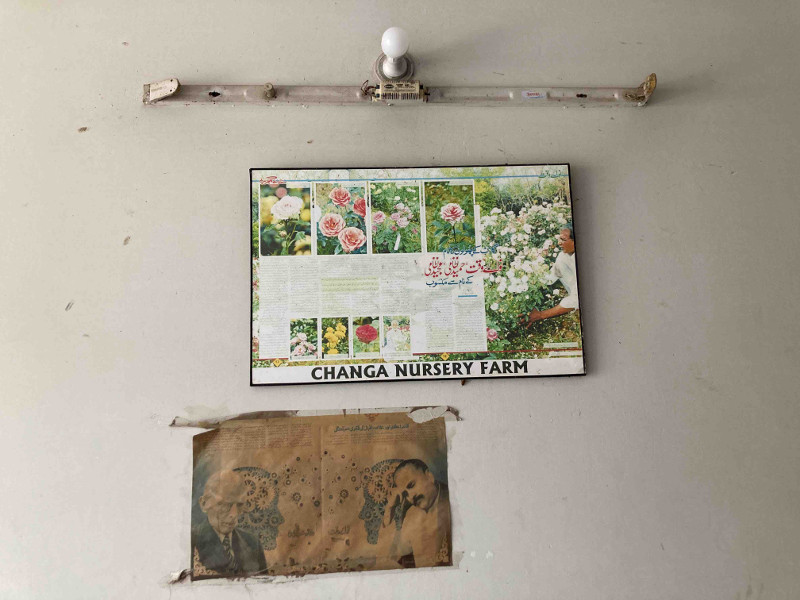

The image from Mr. Changa’s nursery shows a news paper article highlighting the work of Changa Nursery Farms juxtaposed to a newspaper page illustrated with the photos of Pakistan’s national icons, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founding father, and Allama Iqbal, the national poet. Photo by Author

Roses are widely acclaimed for their aesthetic appeal as well as their symbolic attribution with joy and love. The desi gulaab, a shocking pink wild rose, is a ubiquitous sight at Pakistani weddings as well as newly covered graves of cherished relatives and friends. Roses are not just visually attractive but an olfactory and gustatory delight for many. In fact, for cosmetic and beauty products, as well as beverage companies, these qualities of scent and taste alone can become the raison d’être for roses in their supply chains. Rose extracts can be sold for a couple thousand to several tens of thousands of Rupees, whereas rose oils are three times more expensive. “Soap companies will count each and every drop that goes into the mixture because the extracts can be more expensive than gold,” Mr. Changa explained. On the other hand, the state’s lack of interest and financial capacity on resourcing and encouraging local expertise has prompted a constant struggle to be seen. Without a patent, his roses and ideas will not travel the world with the same prestige and recognition that accompanied David Austin’s flowers to Pakistan.

Yet, somewhere between/beyond colonial inheritance of commoditizing relations with nonhuman others and neoliberal governance of globalization, Mr. Changa’s and the roses’ affective and material entanglements unsettle singular readings of human-plant relations. Analyzing his multi-decade association with caring for, experimenting with, promoting, and cultivating roses, along with the ecological history and constitution of Pattoki, shows that it is imperative to locate human and more-than-human social worlds through their “collaborative” (Smith 2016) making of the other.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Mr. Changa and Mr. Najeeb for their assistance with this project.

Footnote

[1] The English Rose, a hybrid variety of roses, are famous for their fragrance, form, and resistance to diseases.

References

Archambault, Julie Soleil. 2016. “Taking Love Seriously in Human-plant Relations in Mozambique: Toward an Anthropology of Affective Encounters.” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 2: 244-271.

De la Cadena, Marisol. 2010. “Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections Beyond ‘Politics.’” Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 2: 334–70.

Haraway, Donna J. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. University of California Press.

Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York, NY: Viking, 1985.

Smith, Mick. 2016. “On ‘Being’ Moved by Nature: Geography, Emotion and Environmental Ethics.” In Emotional Geographies, pp. 233-244. Routledge.