Introduction

When I asked my aunt back in 2014 if my old Game Boy Color was still around, she handed it to me, but confirmed that the A and B buttons no longer worked properly. The Game Boy Color is a handheld game console that was released in 1998 as a successor to the black-and-white Game Boy (1989), though both consoles were discontinued in 2003. My grandmother had died recently, and we were clearing out my and my brother’s belongings from her newly empty house. Truthfully, I hadn’t touched this handheld console since the mid-2000s, around the time I upgraded from the family desktop computer to my own personal laptop. The title stickers on some of the cartridges had begun to wear out, but I held hope that this wasn’t an indicator of what their inside was like, or whether they had reached the end of their lives. I told my aunt I’d find a way to fix the buttons, to which she answered, “Why would you want to repair something from the past when the quality of what’s now in the present, on the market, is infinitely better?” In the mind of many people, it is indeed better to wait for a newer, more technologically advanced model to come out, a manifestation of planned obsolescence which we have learned to live with.

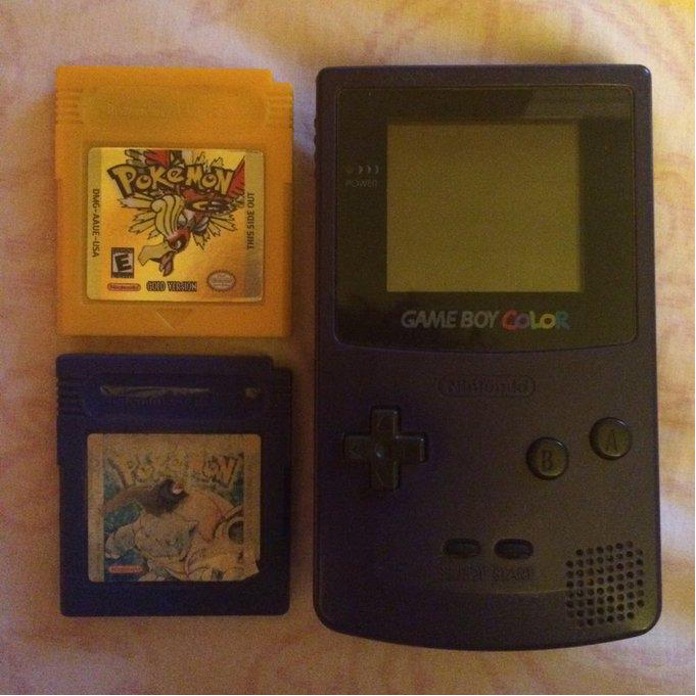

Photo by the author of a purple Game Boy Color with Pokémon Gold and Pokémon Blue cartridges.

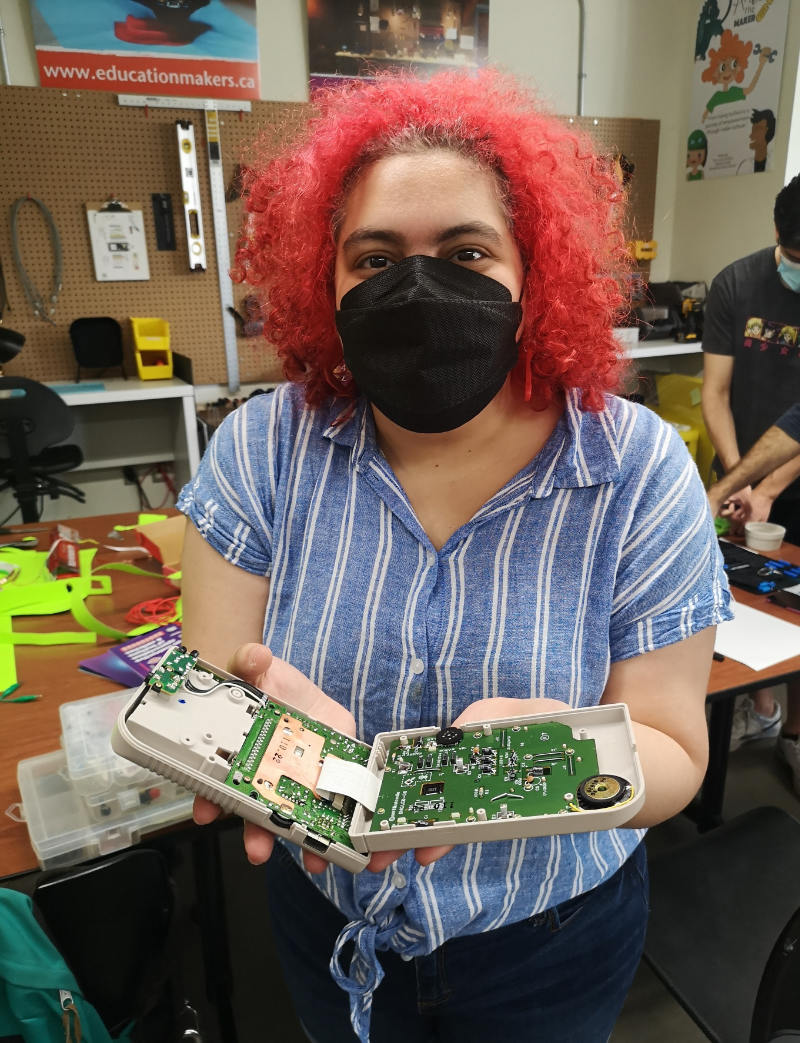

Flash forward to 2022, and I had still not managed to fix the buttons on my deep-purple handheld but I attended a Game Boy Hardware Hacking workshop hosted by Lee Wilkins, with the support of Alex Custodio and Michael Iantorno as part of a series of events leading up to a Solar Game (Boy) Jam. The purpose of this workshop was to hack into the console to alter the way it functions, involving changing the buttons. After a quick presentation, we started by removing the external screws from the Game Boy Color console using an “iFixit” toolkit. We had to use a tri-wing screwdriver because the screws Nintendo uses aren’t the typical Phillips; picture a peace sign Y, instead of a plus sign +. The internal screws were a plus sign (Phillips), however. The point of the screws requiring a different screwdriver is to stop you from getting in, but once you’re in, you’re in. We then took both sides of the case apart slowly, careful not to damage the screen or circuit board.

Photo by Yiou Wang of the author holding the Game Boy they had taken apart.

While concerned with sustainability throughout my whole life, ever since we had a tree-planting day at school when I was eight years old, my main takeaway from the workshop was not sustainability, but that I had been implicated in the process of making. I was made into an actor: not in the theatrical sense, but I had been given a role in making the game instead of just playing it. In other words, I became a “prosumer,” a mix between producer and consumer (Berg, Narayan, Rajala, 2021). I, and the workshop attendees, gained a form of agency that day through hardware hacking.

Becoming the Game

Taking the console apart felt cool, but we still had more to do. We wanted to hack into it and alter some of its functions, particularly the buttons, so the next step involved soldering. I had done some soldering before, with Alex and Michael as well, in May. We had replaced the volatile memory batteries on some Game Boy cartridges, which had to be soldered on the motherboard to stay in place. In the more recent workshop’s case, we soldered the exposed part of the wires onto the buttons and the wires served as extensions of the buttons which we could attach to conducting elements using alligator clips.

After everything was in place, we had to think about movements that would close the circuit on each button. We glued aluminium paper on cardboard to make bracelets, rings, headbands, and other accessories to connect to the alligator clips. Yiou, a visiting scholar, sketched out the positions we would be standing in. We stood in a circle to symbolise a circuit, with Alex holding the console in the middle of the circle. We each wore one or two of the accessories we had prepared earlier. The workshop attendees worked together: in order to move downwards, I would high-five Justin, Justin would (gently) smack Owen’s head to go left, and Richy and Yiou would elbow-bump to go right. Unfortunately, Tetris doesn’t have an upwards function so we couldn’t test Owen and Richy fist-bumping to go up. We modded a Game Boy console to become THE Game Boy console and played the coolest game of communal Tetris ever!

Planned Obsolescence

As I’m writing this, people are preparing for the eShop closure (the electronic Nintendo store through which people can purchase digital copies of games and other programs) on Nintendo 3DS and Wii U consoles by downloading everything they’d purchased before they no longer can, as per Nintendo’s official announcement. The 3Ds, successor of the DS (2004), was released in 2011 while the Wii U, successor of the Wii (2006), was released in 2012. People can still buy second-hand games for both platforms, in the form of physical cartridges, but as of this month (March 2023), they can no longer buy them digitally from Nintendo. This news came around the same time it was announced in Nintendo Direct that classic Game Boy and Game Boy Advance games will now be included in the Nintendo Switch Online membership, in digital form. Fans suspect DS and 3DS games will be next.

As defined by industrial designer Brooks Stevens in 1954, planned obsolescence is a marketing strategy that presumes that electronics are made with the intent that the consumer will want to discard them by the time their successor comes out on the market through “instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary” (Adamson and Gordon, 2003). Many people assume that with planned obsolescence, their electronics will break down immediately, or that their electronics will stop functioning. However, scholars suggest that consumers will be under the impression that their belongings stopped functioning because they don’t function the same way the latest model does (Miao, 2011; Kuppelwieser and Klaus and Mathiou and Boujena, 2019). In other words, it’s not really becoming out of use as much as it would become inconvenient to use them in conjunction with other existing, newer models on the market.

Taking Agency or Being Given Agency?

In a sense, getting into the console to fix a button or switch out the screen are sustainable efforts to combat planned obsolescence, all while giving consumers more agency over what they consume.

In Animal Crossing: New Horizons (2020), the game doesn’t end once the players reach the end credits. After the credits roll, one of the game’s NPCs, or non-player characters, tells the player that they’ve unlocked terraforming, making them an official “Island Designer” who can reshape hills, cliffs, create ponds, move bridges, to personalise their islands a step further than redecorating by putting down items from their pockets. Terraforming even comes with a white hard hat the player must wear every time they’re changing the architecture. This new feature that wasn’t included in previous iterations of the game before 2020 gives the player some form of agency, in my opinion, over what the game they’re playing looks like. In this case, agency was given, thus making it voluntary on the behalf of the development team and different from the agency consumers achieve through hacking and modding.

A form of agency I am more concerned with is people taking the reins of technology for themselves out of a want or a need. When I couldn’t get my Game Boy Color buttons to work in 2014—desperate to play Pokémon Crystal again—my first thought was to give up and purchase a 3DS, which would have newer editions of the game, though not the exact game I wanted to play. But I found a solution: Twitter friends opened my eyes to the world of emulators. To explain it simply, emulators tell a computing platform to operate a certain way that mimics another computing platform in order to run software that only works on a certain platform. Emulators exist for almost any platform and can even be encased in a shell that looks like one of the retro handheld consoles, another form of agency the players themselves have taken. I downloaded a Game Boy emulator onto my laptop and then downloaded a ROM file[1] of Pokémon Crystal that someone had modded to work on an emulator. I had so much fun playing it and reliving my memories, I ended up locking myself in my room for hours and hours every day that summer.

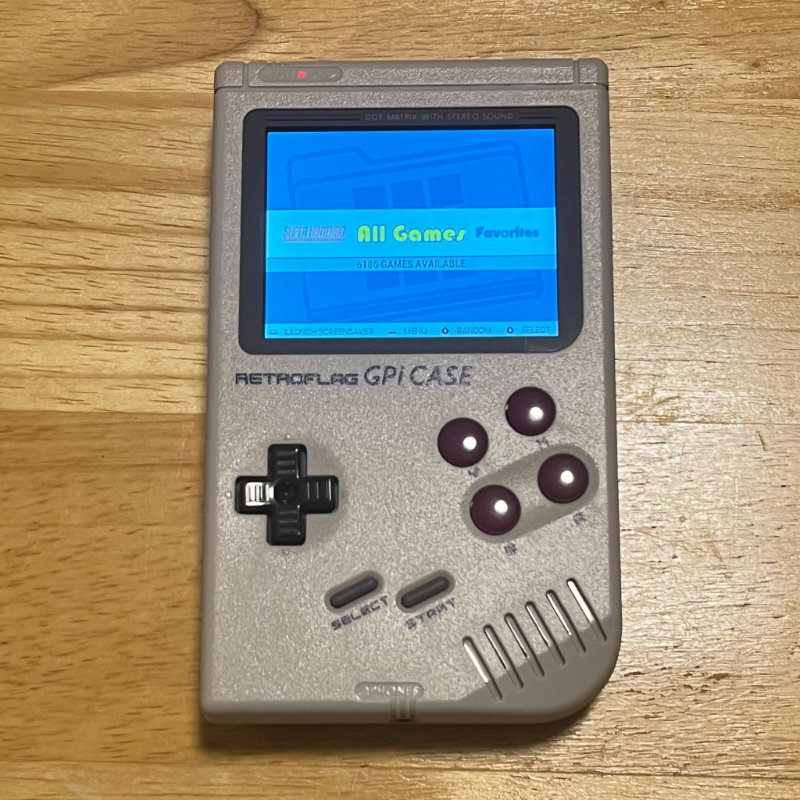

Photo by the author of the author’s Raspberry Pi computer encased in a shell made to look like a classic Game Boy.

Conclusion

As the technology advances, there will be more to consider in the process to stop defunct consoles from ending up in landfills. When it comes to software, emulators have proven to be the way to go to preserve the games. In the case of Nintendo closing down eShops for decade-old handheld consoles, it could be justified as the company choosing to focus their efforts on their current consoles over continuing to invest in supporting older platforms, which requires human labour and financial cost.

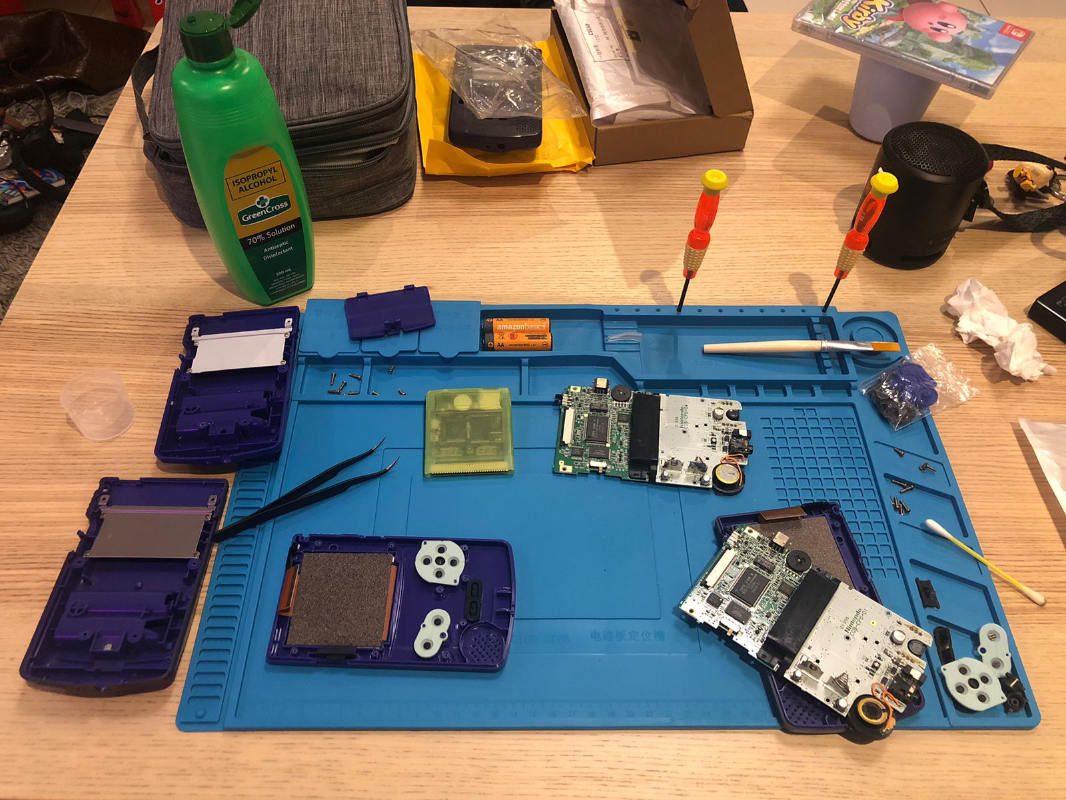

It can be quite scary to not know where to begin or which tools you need to repair or alter electronics, but all you need to do is to start tinkering. I will leave you with my now-functioning Game Boy Color buttons, taken apart, then replaced by my brother—who, just like me, has no background in any of this, but also has a lot of curiosity and doesn’t want to give up on our childhood memories.

Photo by the author’s brother of a workshop area with tweezers, screwdrivers, rubbing alcohol.

Note

[1]Read-Only Memory, the software data present on the game cartridges.

References

Adamson, G., Gordon, D. (2003) Industrial Strength Design: How Brooks Stevens Shaped Your World. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Berg, P., Narayan, R., Rajala, A. (2021) “Ideologies in Energy Transition: Community Discourses on Renewables.” Technology Innovation Management Review 11(7/8): 79-91.

Kuppelwieser, V., Klaus, P., Manthiou, A., Boujena, O. (2019) “Consumer responses to planned obsolescence.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 47: 157-165.

Miao, C. H. (2011) “Planned Obsolescence and Monopoly Undersupply.” Journal of Information Economics and Policy 23(1):51-58.