On October 17th, 2023, two news articles about the Brazilian federal budget circulated on social media. One announced the freezing of R$116 million (US$23.3 million) from the budget of CAPES, the national agency responsible for fostering the training of scientists in Brazil.[1] The other reported that a mere three drugs for rare diseases had accounted for an amount of R$575 million (US$115.6 million) in annual federal spending.[2] These two budgets belong to different departments, and the spending in one does not have a direct connection to the cuts in the other. Furthermore, neither the cuts in science nor the expenses of high-cost drugs are a novelty, but rather issues that frequently appear in the news. However, the coincidence of these news stories circulating on the same day allows us to use them as anecdotes to consider the relationships between the state, science, technology, the pharmaceutical industry, economic dependency, and global circulation.

The three rare-disease drugs in question are produced, marketed, and priced by pharmaceutical companies with headquarters in the USA. Under the constitutional right to health, the Brazilian public health system, SUS,[3] provides listed essential medications for the population, including those with high costs. People with health conditions such as cancer or rare diseases appeal via legal actions against the state to gain access to treatments not regularly available in the system, what is called a judicialization process. Of the three medications mentioned in the news, two are not incorporated into SUS, though the third is being negotiated. Incorporating these drugs into the list would allow the state to negotiate their prices, an important aspect of the system’s financial sustainability. This incorporation is assessed by the National Commission for the Incorporation of Health Technologies (Conitec), following a cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis. But what comes along with this incorporation? Is it enough to solve the health and economic issues of importing highly priced drugs?

Following the medication

In my doctoral research, I set out to follow a medication used to treat cystic fibrosis (CF). The drug comprises a combination of three components, elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor, commercially known as Trikafta. I traced the health technology assessment (HTA) process that would determine its incorporation into SUS. Trikafta, like the previously mentioned drugs, is a high-cost product developed and manufactured by a US-based pharmaceutical company, which, until recently, had restricted access through legal means.

This methodological proposal of following a medication is based on at least two understandings. The first is that medications are powerful material objects with many social implications: they embody meanings, are engaged in trade, are highly mobile, and have the power to transform bodies. Thus, they become commodities of high economic and political value that embody hope for people in distress (Whyte, 2002). The second is that the HTA process in question is part of a complex global system of circulation and trade; therefore, following the medication through the relationships it establishes and the paths it takes is a way to better analyze this object (Marcus, 1995).

The first decision by Conitec regarding Trikafta[4] was non-incorporation, highlighting that while the drug’s effectiveness was undeniable, the costs involved were too high, beyond the established cost thresholds. This initial decision was subjected to public consultation, and after the mobilization of CF associations, researchers, healthcare professionals, and a price renegotiation, the medication was incorporated into SUS. The mobilization of associations and scientific entities in public participation processes, the arguments and strategies employed, and the questioning of cost criteria and thresholds are central aspects of my ongoing doctoral research, which I will publish in future articles.

However, there is a specific aspect of this process that I would like to discuss with international interlocutors, particularly on a US-based blog. Taking Trikafta as a complex social object that engenders multiple relationships, what does a high-cost medication bring with it when it comes from abroad? What relationships are entangled within the medication packaging—entanglements with a healthcare system, with market logic and intellectual property, with evidence produced in clinical trials?

The unequal global pharmaceutical market

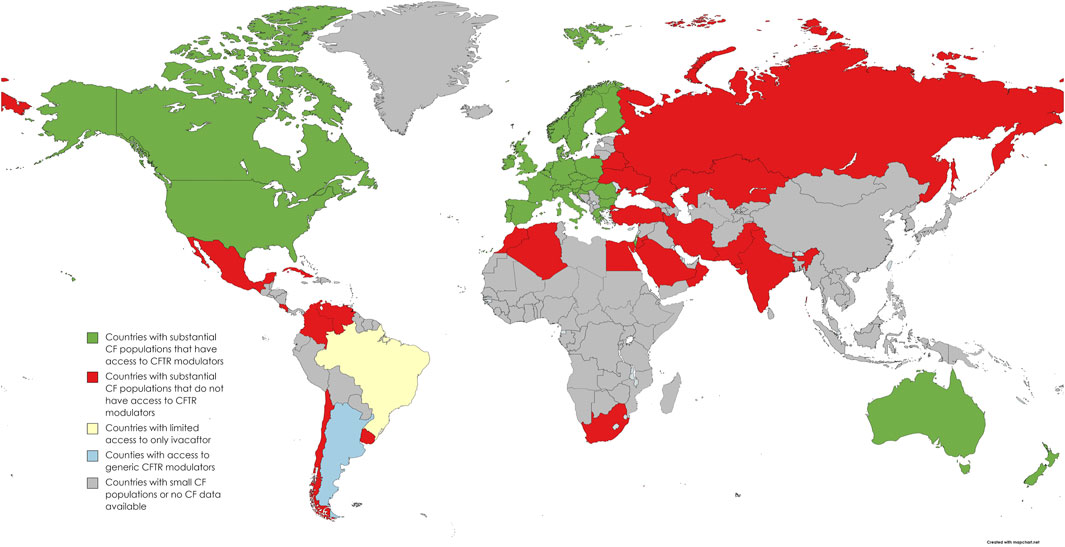

Between the first (negative) and the second (positive) decisions by Conitec regarding Trikafta, the VIII Brazilian Conference of Cystic Fibrosis took place, where I conducted participant observation. The conference brought together all the key actors involved in the HTA process: researchers, healthcare professionals, people with CF, association leaders, and public officials. During the conference presentations, which were generally oriented in favor of Trikafta’s incorporation into SUS, a map was widely shared (Figure 1). This map represents the inequality of access to the medication worldwide.

Figure 1: A map representing access to Trikafta in different countries around the world. (Open source: Zampoli et al. 2023)

Access to the drug closely reproduces the division between a wealthy Western global north and the rest of the world. Since the CF genetic mutation that can be treated by Trikafta is more prevalent in countries in Western Europe or of predominantly white descent populations (such as the US, Canada, and Australia), one could argue that the medication distribution merely reflects a genetic distribution. However, low or middle-income countries with substantial CF populations still lacked full access to Trikafta due to its high prices, as was the case in Brazil, a racially diverse country. Furthermore, as noted by Zampoli et al. (2023), as a consequence of this link between race and genetics, even in wealthy countries, CF populations that identify as non-white have less access to treatments. So, how is this global drug market configured?

In an article on the high-cost cancer treatment market in India, Banerjee (2017) cites an interview in which the CEO of Bayer Pharmaceuticals responds to criticism about the difficulty of accessing an anti-cancer drug, saying that it was not developed for the Indian markets but for Western patients who could afford its cost. This statement indicates that medications come with the assumption of a target population, with a certain income and racial composition.

On the other hand, Biehl and Petryna (2016) point out that Brazil has become a significant target for global pharmaceutical markets. This is not only due to its large population but also because of the specificities of the public health system, which, supported by the constitutional right to health and subject to legal proceedings, must ensure access to high-cost medications through state purchases.[5]

However, I would argue that while incorporation into the list of medications available through the system places the country in a better position to negotiate purchase prices, it alone does not solve the problem of high costs and their impact on the health system budget.

Price policy and research

At the same conference mentioned earlier, a researcher from Trikafta’s Pharma presented new drugs being developed for CF by the company. At the end of her presentation, she was asked by a conference member about the prices that would be charged for these new products. She evaded the answer, stating that she was not involved in pricing.

The researcher separated the dimension of research from the market dimension. On the contrary, when questioned about the prices of their high-cost medications, pharmaceutical companies justify that the price is essential to cover the costs of the research required to enable the development of new drugs. They argue that lowering the prices would be a way to discourage innovation (Banerjee, 2017; Zampoli et al. 2023).

Furthermore, the development of new molecules is paced by international intellectual property agreements, which expire after 20 years of registration. The development of new compositions, combinations, and processes is technical but also market-oriented (ibid.). These cases indicate that the research and development of a medication are closely linked to its circulation and sale. But how much is a fair charge that does not hinder the marketing development of new drugs? Who should set this price?

A published study estimates that the production cost of Trikafta is over 90% lower than the listed value in the USA (Guo et al., 2022). Price negotiations are conducted openly with the Brazilian government, unlike other countries with public healthcare systems. One of my interlocutors at the conference pointed out that this could potentially constrain the company from lowering the price to a level within the threshold established in Brazil, as it could create pressure to reduce prices in other parts of the world.

After negotiation, Trikafta’s incorporation into SUS was approved with a reduction of more than 44% in the projected budget impact, decreasing from R$1.99 billion to R$1.11 billion (from U$400 million to U$232 million) over five years. Nevertheless, this was still a significantly high value that exceeded the parameters established for cost-effectiveness thresholds.

In this process, the medication is not merely a chemical compound but is a product of and produces a network of relationships: with clinical trials and research results, with research subjects and their hopes and activism, with a production industry and its private health logic, with international intellectual property agreements and patent records, with a global drug market. All of this comes imported with the medication packaging when it comes to incorporating the drug into SUS.

What to do?

How to ensure that the global south’s healthcare system budgets do not become increasingly burdened with new high-cost drugs from the north? How can we entangle other relations with medications that would allow healthcare systems to remain viable? How can we establish a more equal global pharmaceutical market?

Compulsory licensing and the production of generics have accumulated many successful cases in the past, such as with antiretroviral medications. However, the current structure of the global pharmaceutical market, the sanctions imposed on those who violate international patent agreements and the current political orientation of different countries do not seem to point in that direction (Banerjee, 2017).

Will activism against pharmaceutical companies succeed in pressuring them to practice fair prices according to different local contexts? Would it be possible for each country to establish their own local, less internationally dependent systems of medication production? Is this still possible amid limitations around national R&D policy, such as the budgetary cuts cited in the beginning of this post? Or would it be necessary to establish the regulation of global drug markets to counterbalance sanctions for patent infringements? Is this possible in a world where multilateral organizations are increasingly weakened? This is an ethical, material, political, and social justice challenge that travels globally within the medication’s packaging.

Notes

[1] https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/educacao/2023/10/governo-lula-bloqueia-r-116-milhoes-do-orcamento-da-capes.shtml

[2] https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2023/10/governo-federal-gasta-r-575-mi-na-compra-de-tres-remedios-para-doencas-raras-por-ordens-judiciais.shtml

[3] SUS is simultaneously a source of pride for us Brazilians but also of complaints, amid ongoing attempts at disinvestment and privatization.

[4] The choice to maintain the reference to the medication in this text by its commercial name ‘Trikafta’ and not by the combination of three molecule names, elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor, besides being a more practical and pleasing writing form (including in marketing strategies (Whyte 2002)), is to emphasize that it is more than just chemical compounds but also a commodity that mobilizes multiple relationships.

[5] It is important to highlight that healthcare being a constitutional right is not a problem in itself; on the contrary, it is an achievement resulting from the mobilizations for Brazil’s democratization in the 1980s. The state should provide access to medications that are inaccessible for one reason or another. It is also worth noting that the demands of people with rare diseases and their families are absolutely legitimate and, in many cases, they represent the only available therapeutic alternatives to ensure an improvement in quality of life and life expectancy.

References

Banerjee D. “Markets and Molecules: A Pharmaceutical Primer from the South.” Medical Anthropology. 2017; 36:4, 363-380, DOI:10.1080/01459740.2016.1209499

Biehl J, Petryna A. “Tratamentos jurídicos: os mercados terapêuticos e a judicialização do direito à saúde.” História Ciênc Saúde-Manguinhos. 2016; 23:173–92.

Marcus GE. “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annu Rev Anthropol. 1995; 24:95–117.

Whyte SR, van der Geest S, Hardon A. Social Lives of Medicines. Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Zampoli M, Morrow BM and Paul G. “Real-world disparities and ethical considerations with access to CFTR modulator drugs: Mind the gap!” Front. Pharmacol. 2023; 14:1163391. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1163391