This post explores the surveillance of letters across two time-periods in postcolonial India: mail letter interception immediately following India’s independence in 1947, and the contemporary use of letters as incriminating evidence against human rights activists in the ongoing Bhima Koregaon-16 (BK-16) case.[1] The BK-16 is a group of activists including academics, journalists, lawyers, artists, poets, and dissenters who were imprisoned through a series of coordinated arrests by the police in different parts of India June 2018 onwards. They were arrested under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), India’s anti-terror law that empowers the government to arrest citizens without any judicial process. Many of them are Dalits, representing India’s most marginalized caste. The BK-16 advocate for the human rights of India’s poorest and most oppressed communities, and overtly oppose the ideology of Hindutva, a Hindu supremacist nationalism espoused by the ruling Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) since 2014.

In June 2018, the Pune Police arrested Rona Wilson, a notable activist among the BK-16 who worked with the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners before he was arrested from his residence in Delhi. Pivotal evidence used in the BK-16 case consists of ten letters that were discovered on Wilson’s computer, which purportedly establish connections between the group and a banned militant organization. These letters also allegedly disclose a conspiracy to assassinate the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. However, prior to the arrest, the letters were fabricated and planted on Wilson’s computer during a sustained twenty-two-month attack using commercially available malware called NetWire.[2]

Through a heuristic juxtaposition of paper letter interception in the aftermath of India’s independence, and the planting of fake digital letters on Wilson’s computer, this post focuses on a shift in the political mediations that characterize targeted surveillance and imprisonment in India. While letter interception in the earlier decades of postcolonial India was a means to incriminate people based on evidence of “objectionable behaviour” and ideas, the BK-16 case shows how surveillance in contemporary India is a premeditated and pre-mediated endeavor to incarcerate activists, journalists, lawyers, artists, and academics.

I refer to the various surveillance media practices that underpin the technological and legal procedures of targeted political imprisonment—from recording and observing to hacking and planting “evidence”—as premediations of carcerality.[3] Such premediations vary between mass and targeted surveillance and, in the case of the BK-16, have changed from surveillance as passive observation to surveillance as orchestrating incarceration. This change denotes a shift where the ‘medial a priori of carcerality’ (surveillance media leading to incarceration) turns into the ‘carceral a priori of media’ (incarceration as the objective of surveillance media). Catalyzed by the easy availability of mercenary spyware like Pegasus (developed by the Israeli firm NSO), and a shift from analog to digital technologies, it highlights multiple facets of how politics and media intersect in contemporary India. The political rationale behind the fabrication and planting of letters on Wilson’s computer was not just incarceration but also the mediatization of such “evidence” through news and social media to shape public opinion and discourse regarding activists and dissenters in India.[4] Premediations of carcerality thereby encompass both the digital mediations of hacking and planting “evidence” with an objective to incarcerate, as well as a statist anticipation of the mediatizations of such “evidence” and arrests through various channels of media circulation.

Intercepted Letters, Suspect Lists, and Police Reports

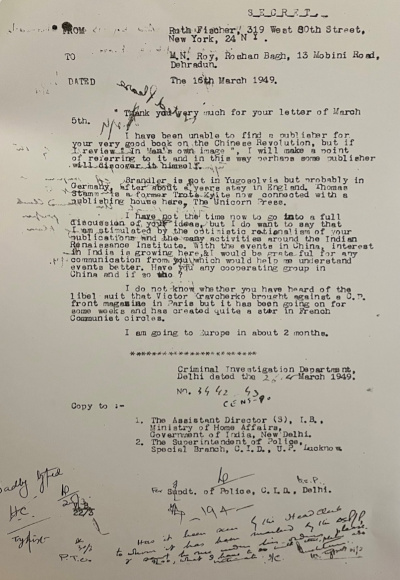

During the summer of 2022, while working at the archives in Delhi, I was immersed in reading hundreds of intercepted letters dating back to the 1940s and 50s. The experience was an uncomfortable one as I could not shake the feeling of being an intruder rather than a scholarly observer. Among the intercepted missives were heartfelt expressions of lament addressed to family members who had migrated to Pakistan, clandestine directives on smuggling money and gold that was being confiscated at the newly demarcated India-Pakistan border, poignant love letters intercepted as encrypted communication, and politically charged exchanges ranging from the self-determination of Kashmir to the complexities of the Korean and Cold Wars. A letter addressed to the Indian Marxist revolutionary MN Roy, who was surveilled and tracked across the world, also appeared in the archival records (Figure 1).[5] The letter was from Ruth Fischer, founder of the Austrian Communist Party, who was unable to find a publisher for Roy’s book on the Chinese Revolution, and had news about comrades and communism in other parts of the world.

Figure 1. Intercepted letter from Ruth Fischer, New York, to MN Roy, Dehradun, Criminal Investigation Department (CID), March 1949, image by Author[6]

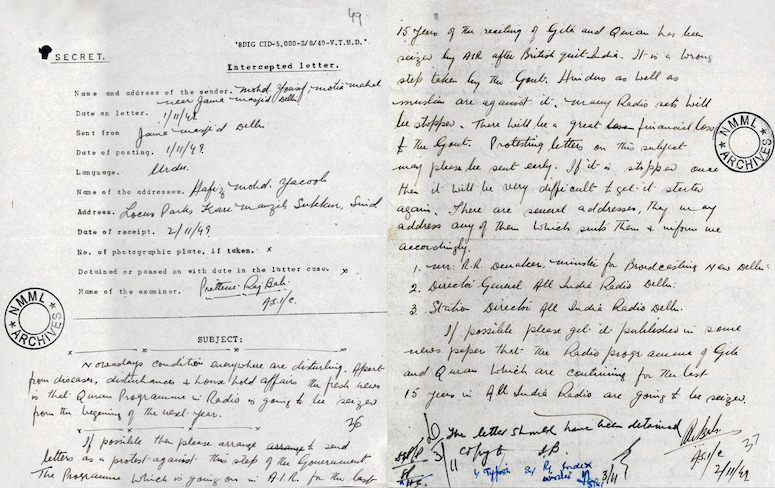

By examining the signatures on these intercepted letters, it became apparent that a police official sifted through the letters at the General Headquarters of the Post Office in Delhi before they were allowed to be posted. For instance, Figure 2 features a letter outlining plans for a protest after the Gita and Quran recitation programmes on All India Radio were discontinued following India’s independence. This particular letter was copied on a standardized form for intercepted letters by a police official. The hand-written or typed letters were then ratified by senior officers who decided whether they should be dispatched or detained. Copies were routinely forwarded to other law enforcement agencies, and in many instances, to the Intelligence Bureau (IB), now one of India’s internal security agencies. The remark at the end states, “The letter should have been detained. Copy to IB.” As is evident from the multiple official annotations that these letters bear, paper was not only a medium of recording and storage, but a tool of bureaucratic decision making, as Cornelia Vismann’s (2008) and Matthew Hull’s (2012) work has astutely shown.

Figure 2. Intercepted letter, Criminal Investigation Department (CID), August 1949, image by Author[7]

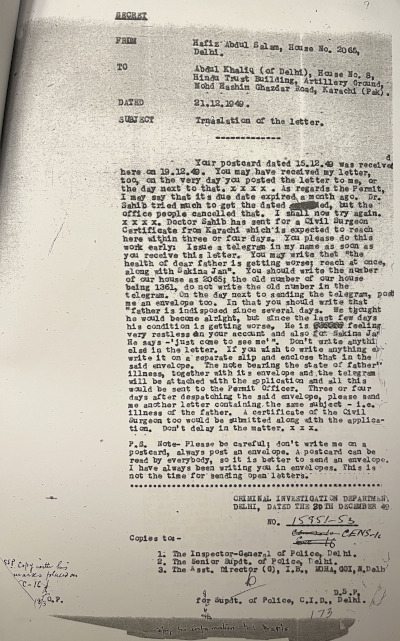

Letter writers, in response, were devising their own tactics to evade surveillance. One person in Delhi corresponded with a family member in Karachi discussing a plan to cross the border under the pretext of his father’s ailing health. He warns the recipient to send envelops instead of postcards because the former was less likely to be scrutinized (Figure 3): “P.S. Note – Please be careful; don’t write me on a postcard, always post an envelope. A postcard can be read by everybody, so it is better to send an envelope. I have always been writing to you in envelopes. This is not the time for sending open letters.”

Figure 3. Intercepted Letter, Criminal Investigation Department (CID), December 1949, image by Author[8]

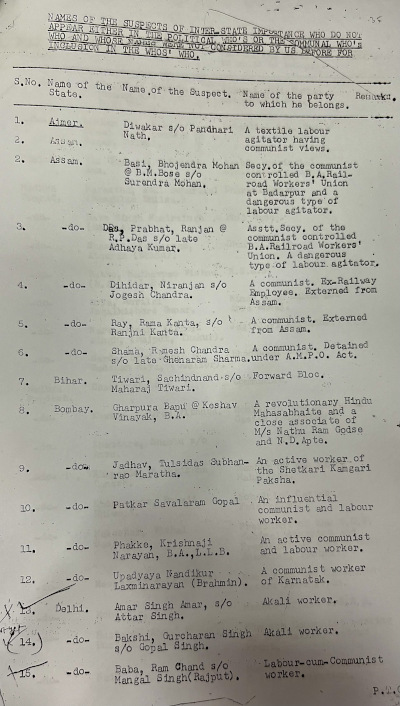

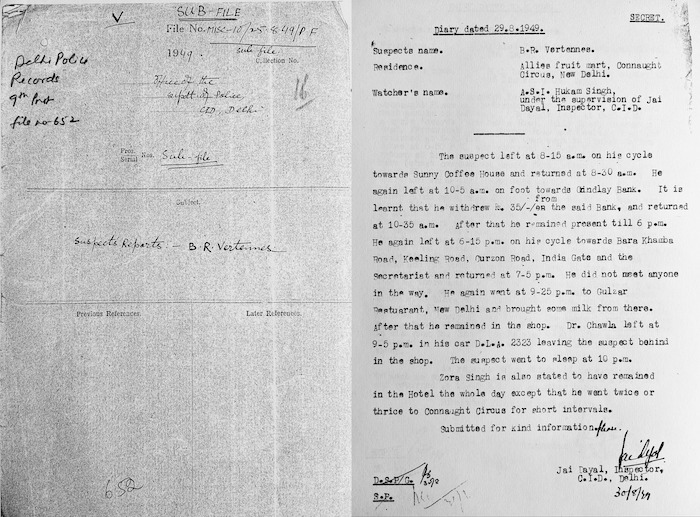

While letter interception served as a method of mass surveillance, it was accompanied by other scribal and paper-based forms of targeted surveillance such as suspect lists, directories, history sheets and police journals. In a police department file from 1953, I came across “suspect lists,” one of which had a rather elaborate title (Figure 4): “Names of the suspects of inter-state importance who do not appear either in the Political Who’s Who or the Communal Who’s Who and whose names were not considered by us before for inclusion in the Who’s Who.” These suspect lists and Who’s Who directories were continuations of colonial surveillance practices after India’s independence. The suspect lists contained the names of various suspects and the reasons for surveilling them, some of which included “a textile labour agitator having communist views,” “Staunch anti-Indian and pro-Pak spy,” and “Member of the Scheduled Castes Federation,” among others. Suspect lists also had corresponding history sheets or reports, which were detailed dossiers prepared by the police documenting the profiles, whereabouts and everyday activities of the suspects being surveilled (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Suspect List, Delhi Police Records, 1953, image by Author[9]

Figure 5 displays a segment from a 1949 suspect report where an individual named BR Vertennes and his friends were constantly under watch. In addition to documenting Vertennes’ daily activities, the report unveils a practice wherein not only the primary target but also their acquaintances, including friends and family, are subjected to continuous monitoring. More often than not, targeted surveillance exploits personal and intimate connections for political ends. An illustrative historical example of surveilling the intimate lives of targets are Las Carpetas (The Files), which encompassed extensive dossiers on more than 100,000 citizens in Puerto Rico spanning from the 1930s to the 1980s. These files served not merely as classification documents but as detailed records chronicling the most private aspects of individuals supporting the independence movement and considered politically dissenting by both the FBI and the Puerto Rican Police Department (Blanco-Rivera 2005).

Figure 5. Suspect Report of BR Vertennes, Delhi Police Records, August-September 1949, image by Author[10]

In contemporary India, paper documentation persists, with suspect dossiers encompassing extensive social media details and WhatsApp correspondences. A notable instance is the ongoing case against Umar Khalid, a student activist falsely charged for instigating communal violence in Delhi in 2020. The Delhi police compiled an excessively lengthy chargesheet of approximately 10,000 pages in the case and amassed around 1,100,000 pages of data, much of which relied on Khalid’s call records and WhatsApp exchanges.[11] During a conversation with a lower-ranking police official in India last year, I discovered the ease with which police departments can access WhatsApp communications of suspects. “Have you used WhatsApp on your computer? That’s how we can view all messages on our screens,” he explained. Furthermore, he revealed the existence of specialized IT units within Indian police departments, comprising non-governmental contract professionals tasked with cyber surveillance and hacking. While traditional methods like intercepted letters have historically been used for surveillance, Umar Khalid’s case underscores a shift where paper dossiers are used for intimidation, and surveillance activities are no longer shrouded in secrecy. Instead, there is a trend towards the mediatization of intelligence through interactions with mainstream media, journalists, and its circulation on social media platforms.

Fabricated Letters, Mercenary Spyware, and Cyberhacks

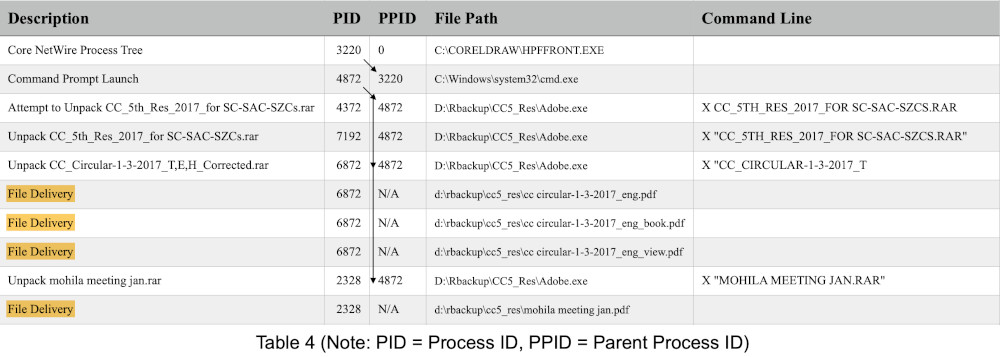

The letters planted on Rona Wilson’s computer mentioned the BK-16’s connections with a banned Maoist group, intentions to destabilize the BJP government, friendly ties with the opposition party, and a plot to assassinate the Indian Prime Minister. Subsequent investigations revealed that Wilson was being digitally surveilled and attacked since at least 2013 and his phone was also targeted with Pegasus (Hegel and Guerrero Saade 2022). Additionally, devices of other BK-16 activists were subjected to various spyware attacks. Both NetWire and Pegasus fall under the category of Remote Access Trojans (RATs), enabling remote administrative access to the compromised devices. In their analysis of Wilson’s computer, a Massachusetts-based digital forensics firm, Arsenal Consulting, has shown how at least 32 documents were planted in hidden folders on Wilson’s computer, including the ten incriminating letters.[12] A table included in one of their reports illustrates the “file delivery” of some additional documents (as PDFs and Microsoft Office files) on January 11, 2018 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Table from Report II by Arsenal Consulting, Submitted in the Court of Special Judge, National Investigation Agency (NIA), India, March 2021, image by Author[13]

Spyware attacks in India and elsewhere are also human-intensive. A RAT operator, also known as a “ratter,” “interacts with each victim individually, scouring through the victim’s file system, spying on the victim through the webcam and microphone, or harassing the victim using the computer’s speakers and user interface” (Farinholt et al. 2020: 2109). Arsenal’s reports also stated that the attacker had access to extraordinary resources, including time, to execute the malware attacks. Beyond hackers-for-hire remotely infiltrating devices, there exists a thriving industry where hackers sell software vulnerabilities to the cyberweapons sector.[14] This enables the functioning of spyware like Pegasus, NetWire, or DarkComet.

The tampering of legal evidence is a commonplace occurrence in India. What makes the BK-16 case different is the extent of planning and time that was invested to premediate carcerality, with a probable assumption that traces of tampering are hard to detect in cyberspace. The fabrication of evidence also relies on the confiscation of devices such as computers and phones, which are consequently difficult to access by counter-forensic organizations across the world. An important reason for planting evidence comes forth in an observation made by the American Bar Association in one of their reports on the BK-16. Highlighting their concerns regarding prejudice against the imprisoned activists, they state that:

The Maharashtra police has repeatedly resorted to press conferences where baseless allegations that are not substantiated by the F.I.R. or evidence and are prejudicial to the accused, have been made…The police further released to the press several documents which they claimed were letters written by and to the arrested persons…Moreover, in trying to implicate a number of unrelated and prominent critics of the current regime in a plot to murder the Prime Minister, prosecuting agencies appear to be constructing a straw man in order to sensationalize the case.[15]

Repeated press conferences, leaking of (fake) evidence and documents, and attempts to sensationalize the case by the Maharashtra police signal how surveillance and policing in India anticipate the mediatization of arrests, and hence the shaping of public opinion in relation to dissent.

Conclusion

While this post traced how the premediations of carcerality changed from surveillance as passive observation to surveillance as orchestrating incarceration, I would like to conclude by reflecting on the nature of some of the material that makes surveillance research possible. The revelation of fabricated evidence and spyware attacks in India and globally owes much to the work of and collaboration amidst counter-forensic organizations such as Amnesty International, The Citizen Lab, SentinelOne, and others. Arsenal Consulting’s forensic analysis in the BK-16 case played a pivotal role in uncovering evidence of fabrication. Some of the surveillance files and intercepted letters I encountered in the archives had instructions about their destruction. I wondered how these files reached the archives despite orders of being destroyed, and realized the significance of reading something that was not supposed to be a part of any official record. Some of the other material I found explicitly stated how surveillance files were routinely destroyed by intelligence agencies. Recently, the Indian government implemented legal amendments permitting the destruction of surveillance reports on orders from Union and State secretaries within six months.[16] It is important to note that on many occasions, if not always, research on policing and surveillance requires either a serendipitous encounter with leaks and traces, risky revelations by whistleblowers and journalists, or counter-forensic work done by organizations to expose such practices across the world. The premediations of carcerality are thereby, more often than not, studied through the postmediations of leaks and traces that are left behind. Such postmediations by counter-forensics experts, activists, lawyers, and journalists are sometimes the only recourse to justice for the wrongly incarcerated.

Notes

[1] For more information on the Bhima Koregaon case, see Shah (2024). For a quick overview and timeline of the case, see: “Bhima Koregaon Case: A Timeline of What Has Happened So Far.”

[2] Forensic research by SentinelOne revealed that the attacks were taking place since at least 2013. See “Incriminating Letters Were ‘Planted’ on Rona Wilson’s Laptop: US Digital Forensics Firm.”

[3] I do not use premediations in Richard Grusin’s (2010, 2) sense of the perpetuation of a “constant, low-level fear or anxiety of another terrorist attack” post 9/11.

[4] For the mediatization of political events, see Cody (2023).

[5] For more on how MN Roy was chased across the world, see Gautam Pemmaraju, “The Dragnet,“ Fifty Two, 3 February 2022.

[6] Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Delhi: Delhi Police Records, 8th Installment, File No. 379.

[7] Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Delhi: Delhi Police Records, 2nd Installment, File No. 66, 1-15 November 1949.

[8] Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Delhi: Delhi Police Records, 2nd Installment, File No. 68.

[9] Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Delhi: Delhi Police Records, 8th Installment, File No. 379.

[10] Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Delhi: Delhi Police Records, 9th Installment, File No. 652.

[11] See “Delhi riots: Police file 10,000-page chargesheet against 15 accused under UAPA & other sections,” The Indian Express, 16 September 2020, and “Northeast Delhi violence: Have to confront Umar Khalid with ’11 lakh pages of data’,” The Times of India, 15 September 2020.

[12] See Neha Masih and Gerry Shih, “Indian activist charged with terrorism was targeted by hackers linked to prominent cyber espionage attacks, new report finds,” The Washington Post, 10 February 2022.

[13] Arsenal Consulting, “Report II: In the Court of Special Judge NIA, Mumbai, Special Case No. 414/2020, National Investigating Agency vs Sunil Pralhad Dhawale and others,” 27 March 2021.

[14] For related research on hacking, see The Citizen Lab’s report by John Scott-Railton et al, “Dark Basin: Uncovering a Massive Hack-for-Hire Operation,” (2020) and Illis and Stevens (2022).

[15] American Bar Association: Centre for Human Rights, “Preliminary Report: Arrest of Indian Attorneys and Activists in Apparent Retaliation for Human Rights Work,” (2019): 8.

[16] See Aditi Agrawal, “Interception and monitoring records to be deleted within 6 months: MeitY,” Hindustan Times, 27 February 2024.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Alex Rewegan, Paige Edmiston, and Katie Ulrich for their extremely helpful editorial engagement and comments on this post.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Alex Rewegan

References

Blanco-Rivera, Joel A. 2005. “The Forbidden Files: Creation and Use of Surveillance Files Against the Independence Movement in Puerto Rico,” The American Archivist 68: 297-311.

Cody, Frank. 2023. The News Event: Popular Sovereignty in the Age of Deep Mediatization (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2023).

Farinholt et al. 2020. “Dark Matter: Uncovering the DarkComet RAT Ecosystem,” Proceedings of The Web Conference 2020, Taipei, Taiwan. ACM, New York, NY, USA.

Grusin, Richard. 2010. Premediation: Affect and Mediality After 9/11 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

Hegel, Tom and Juan Andres Guerrero Saade. 2022. “Modified Elephant Apt and A Decade of Fabricating Evidence,” SentinelLABS: 1-19.

Hull, Matthew. 2012. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan (Oakland: University of California Press).

Illis Ryan and Yuan Stevens. 2022. “Bounty Everything: Hackers and the Making of the Global Bug Marketplace,” Data & Society: 1-87.

Shah, Alpa. 2024. The Incarcerations: BK-16 and the Search for Democracy in India (London: Harper Collins Publishers).

Shantha, Sukanya, “Incriminating Letters Were ‘Planted’ on Rona Wilson’s Laptop: US Digital Forensics Firm,” The Wire, 10 February 2021.

Vismann, Cornelia. 2008. Files: Law and Media Technology (Redwood City: Stanford University Press).