Figure 1: The entrance of the museum at the metro station reads, “Learning is possible through encounters.”

Multisensory Encounters with the “Others”

Since February 2023, I have been conducting fieldwork on disabled women’s access to and experience of infrastructure under the current populist authoritarian government in Turkey. My research has taken me, among other places, extensively throughout Istanbul, the city with the largest disabled population in the country. I have traveled primarily by public transportation to meet with my interlocutors, most of whom are blind, allowing me to experience urban infrastructures alongside them. While passing through Gayrettepe Station, one of the busiest subway stations in Istanbul due to its location in a business district and near an upscale shopping mall, I observed a sentence written on a black background with white neon points: “Learning is possible through encounters” (Öğrenmenin yolu karşılaşmaktan geçer).

This area is home to a museum called “Dialogue in the Dark” and “Dialogue in the Silence,” which provides a multisensory corporeal experience of blindness and deafness targeting non-disabled people as an audience. The museum draws inspiration from other “Dialogue in the Dark” museums located in Europe, and was established by a civil society organization. These museums are significant initiatives aimed at helping non-disabled people understand how “others” experience the built environment, thereby raising awareness about the inequalities and injustices that disabled people may encounter in their daily lives. Disability activism is relatively new in Turkey and values any effort that contributes to the recognition of disability as an identity, which has not been widely acknowledged. Indeed, creating a space for encounter is crucial for cultivating a culture of pluralism, understanding, and care for one another, all of which are crucial for a democracy. In some countries, populist movements are explicitly hostile to disabled folks, and/or ridicule them (e.g. Trump in the US), however, this is not the case in Turkey (disabled women face other challenges, as we will see). So, such initiatives regarding disabled people are quite welcome, as they may contribute to Turkey’s democratization and the inclusion of non-normative bodies and existences.

While contemplating writing this piece, I recalled Joan Scott’s classic article, “The Evidence of Experience.” I found it particularly compelling for its emphasis on the significance of accounting for the lives of often-overlooked others (e.g. ethnic, religious, racial, or gender minorities) in producing more realistic accounts of history and society. However, while expressing her sympathy with such gestures, Scott is critical of attempts to ground people’s identities in the truth of their experiences. After all, Scott reminds us, experiences are effects that are produced by structural features of the world, among them power. Especially for disabled individuals who are extensively marginalized and stigmatized in an ableist world, it is crucial to emphasize the social, cultural, and political constructions of disability within different contexts, rather than viewing it as a foundational, one-size-fits-all experience. This museum can be seen as an attempt to make disability an identity by having non-disabled folks “experience” it. This is meant to instill in people an appreciation of how people different from “us” live, through experiencing things that they might experience. It can also help one realize how infrastructure is experienced unevenly, and in undemocratic ways, as one navigates through exhibits mimicking real everyday spaces.

However, there are some unacknowledged aspects of this museum that, despite their intentions, may be counterproductive. I recall some of my blind activist friends mocking the museum for not accurately reflecting the real experiences of a blind person living in Istanbul, as they were aware that the museum presents disability as a foundational experience devoid of relational constructions of ableism as a system in Turkey’s socio-cultural context. They expressed a desire to create an alternative museum, to show non-disabled individuals what it is truly like to navigate Istanbul as a blind person: “You will fall from the subway platform. As you walk, someone will slip 20 liras into your hand out of pity. You will hit a tree because the guide track ends with a tree. People look at you, and thank Allah for not making them disabled.” All these experiences have been shared by most of my interlocutors during my ethnographic fieldwork, as infrastructure in Istanbul is inaccessible for not only blind folks, but also those who use crutches or a wheelchair for their mobilities.

I was curious about the museum because, despite criticism from my disability activist friends, it is widely praised on social media for educating people about disability. However, one might obviously question how it is possible to gain awareness of a life-long experience in just one hour. I visited the museum with a friend who is not disabled, and has little knowledge about the social, cultural, and political constructions of disability in Turkey. Prior to our visit, I purchased two tickets online for each multisensory experience, costing a total of 800 liras ($24.20). This price is prohibitively expensive for many working-class people in Turkey, given that the minimum wage is $578.31 per month, and the average rent for an apartment is $605. Most of my disabled interlocutors cannot afford to visit this museum because they are unemployed and rely on state cash payments of approximately $152 per month to sustain their lives. Although the museum aims to facilitate encounters between disabled and non-disabled people, it is evident that such interactions are limited to certain groups, primarily those belonging to the upper and upper-middle classes.

Alongside the intended effects of empathy, and solidarity, what other effects does commodifying disability as an experience have? In this post I explore how disability is depoliticized when it is reduced to an individual, sensory experience within technologically reproduced spaces, isolated from the social, cultural, and political constructions of disability in Turkey. Does the sensory experience of disability reveal new ways of understanding the other? I engage with Scott’s critique of experience as foundational, that is, a view that considers “individuals who have experiences” rather than “subjects who are constituted through experience” (1991, p. 779). I see the sensory experience focus of this museum as emblematic of an individualized approach to disability that, while well intended, may counter-intuitively decreases the possibility and potentiality of genuinely improving disabled folks’ lives.

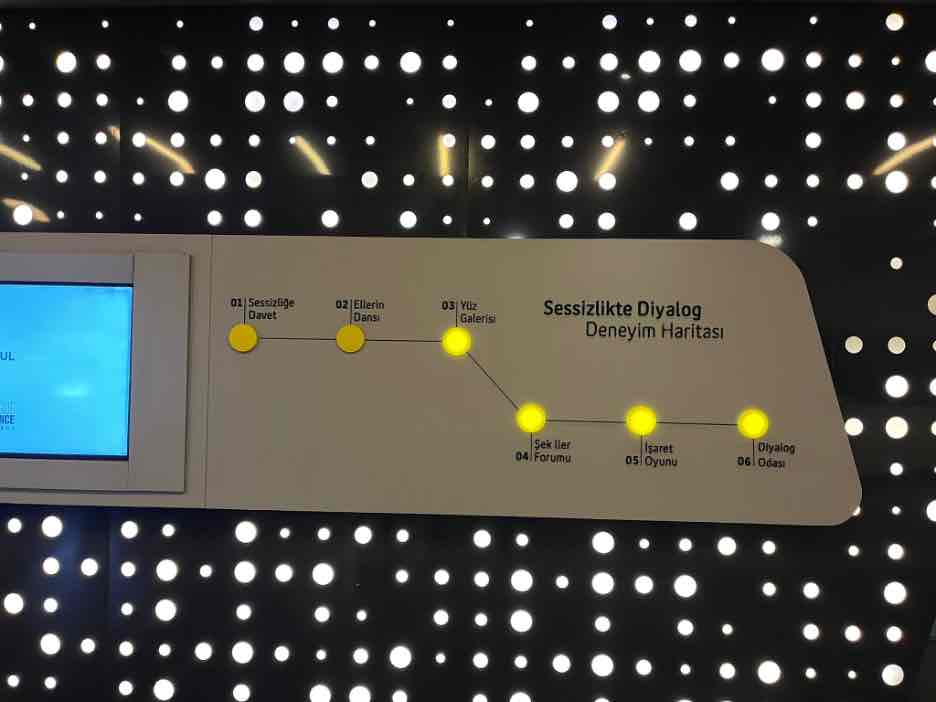

Figure 2: The figure presents an experience map of “Dialogue in the Dark” against a grey background. The map outlines six consecutive stops, each represented by different icons (e.g., trees, marketplace, tram, cinema, cricket, ship, coffee cup). As visitors complete each route, the corresponding icon illuminates in yellow. Image by the author.

Experience 1. Into the “Dialogue in the Dark”

During our visit to “Dialogue in the Dark,” a blind woman guided us along with six other participants. We were given white canes to navigate rooms that were completely dark. She instructed us on how to use the canes and guided us through simulations of features of Istanbul’s infrastructure, such as sidewalks and public transportation, where blind individuals face significant accessibility challenges commonly. She assisted us in crossing a street, boarding a tram with high steps, getting on a ship, finding our seats in a cinema, and buying items in a café. She emphasized the importance of voiced traffic lights and stop announcements, many of which do not function in Istanbul because able-bodied individuals find the noise disruptive or because the systems do not work properly. For example, it is not uncommon for bus drivers to shut off audio announcement systems even when they are properly working.

Like elsewhere in the world, ableism is a defining feature of Istanbul’s urban public infrastructure, which is not made with disabled people’s experiences in mind. As we navigated the darkened room, she asked how we felt. The museum aims to evoke emotions through embodied and sensory experiences. Participants expressed anxiety and worry due to the darkness and obscurity, immediately associating blindness with negative emotions. However, I observed that many were also laughing while moving through the room, treating it as a one-hour “activity” they paid to “experience.” Many had never encountered a blind person before, highlighting the exclusion of disabled individuals from social and cultural life in Turkey, including in schools, streets, hospitals, cinemas, and cafes. The museum’s creators have developed an experiential space that apparently aims to to evoke empathy, which is not bad as far as it goes, but it does so in a way that is also devoid of the social and political context of disability policy and politics in Turkey, expecting to evoke empathy. The market and profit-driven nature of neoliberalism have significantly influenced the reconstruction and redevelopment of urban spaces, often excluding marginalized groups, particularly disabled folks. This approach reflects the reproduction of neoliberal values, such as the commodification of all sectors of society (Brenner & Theodore 2002; Collier 2005). Even disability is being turned into a marketable and purchasable commodity.

Does such a multisensory experience prompt participants to question the power relations between disabled and non-disabled individuals? Or does it perpetuate a medical model of disability that considers disability solely as a sensory experience of individuals? The two-model approach dominated disability studies for decades. The medical model of disability situates disability within the body of an individual, framing it as a condition to be ‘corrected’ through biomedical interventions. This approach has been criticized for relying on “biomedical models of causation” and an “ahistorical classification of bodies” (Connell 2011). Alison Kafer (2013), for example, critiques the medical model for depoliticizing disability by failing to contextualize it within social, economic, and cultural fields. In contrast, the disability rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s differentiated itself from the medical model by asserting that disability is a consequence of social environments rather than a lack of bodily capacity. Disability studies have built upon this latter perspective to analyze how disability is socially, culturally, and politically constructed. It is not merely the corporeal experiences of disabled people, but the “capacity of social structures and cultural discourses” (Connell 2011) that shape one’s experience. The social model of disability has been instrumental in discussing the material barriers that hinder disabled people’s participation in everyday life, offering a valuable perspective on the link between infrastructure and disability. Most of my interlocutors, disability activists in Turkey, reject the medical model of disability and therefore criticize the museum for perpetuating this model, which focuses on the individual experience of being blind. For example, none of the participants asked the guide how she deals with inaccessible spaces in Istanbul or how she learns everyday tactics to navigate such infrastructure. They only inquired if she could see any light, if she was born “this way” (referring to blindness as a negative experience), or if she can imagine the colors of things like the sea. They did not ask how she feels living in an inaccessible city or what she expects from an accessible one.

We experienced the room through our bodies and other senses, such as touch and sound, which was a new experience for the non-blind participants and should have reversed the power relations between the blind guide and the non-disabled participants. However, this did not happen because the museum only created a space for shared embodiment among the participants, all able-bodied and not blind. It did not seem to me that participants gained an appreciation for a blind person who creates multiple ways to navigate these spaces through mastering touch and sound, but rather experienced a moment of “gratitude” for not being blind or disabled. It did not facilitate a genuine interaction between the blind guide and the non-disabled participants. This is because the museum is designed for able-bodied people as a sterile experience for their spare time —and a quite expensive one at that.. The museum would be more effective if it offered a space to discuss how disabled people rely on their affective labor to compensate for the absence or inadequate infrastructure.

Figure 3: Set against a grey background, the figure displays feedback from visitors, written in black letters. The comments include: “Darkness is not something you need to fear,” “If there is dialogue, there is no darkness,” “Thank you for the enlightenment I experienced,” and “You open our eyes in the dark.” Image by the author.

Disability Beyond an Isolated Affect

While the museum may aim to create a space for encounters among diverse bodies and experiences (in fact, ironically, physically disabled people cannot visit the museum because it’s not accessible to them, especially for those using wheelchairs), such openness frequently engenders a fear of blindness rather than fostering an understanding of it as an alternate mode of existence. Fear is not an isolated affect. As Sara Ahmed writes (2004) “fear might be concerned with the preservation not simply of me but also us or what it is or life as we know it or even life itself.” Blindness carries negative connotations within Turkey’s social, cultural, and political context. For instance, I heard participants express sentiments like, “I would rather die than be blind. It is so difficult to live like this. Who will teach me to use a white cane? Where would I go if I became blind?” This perspective frames blindness as a vulnerability, which evokes fear among able-bodied individuals. The underlying issue is that disabled people are not recognized as political subjects with rights, which frames disability as a human rights concern. What happens when a technologically designated space intended to foster empathy instead perpetuates unwanted emotions and conclusions? It risks depoliticizing disability by reducing complex social and environmental phenomena to emotional reactions and experiences. If knowledge or experience is considered universal and accessible to all, it neglects the essential dynamics of politics and power (Scott 1991).

Figure 4: This figure presents an experience map of “Dialogue in the Silence” on a grey background. It outlines six sequential stops, each represented by different games: Invitation to Silence, Dance of the Hands, Face Gallery, Forum of Shapes, Sign Game, and Dialogue Room. As visitors complete each route, the corresponding icon illuminates in yellow. Image by the author.

Experience 2. Into the “Dialogue in the Silence”

This was also quite obvious in the “Dialogue in the Silence” section of the museum. This section comprises several rooms, each with a different theme and games designed to help participants understand how deaf folks use their hands to communicate. Upon entering, we were given headphones to block out sound, and a deaf guide instructed us not to speak during the session. For example, we were shown pictures of various hand signs and asked to guess their meanings. I was shown a picture containing animals and geometric shapes, and I had to describe it using sign language. My friend then attempted to recreate the same picture using three-dimensional figures. Participants were all laughing and appeared to enjoy the activities, which annoyed me a lot. I have been learning Turkish sign language and engaging with deaf women in different disability organizations in Istanbul for my fieldwork. Deaf people are significantly marginalized in Turkey, facing numerous challenges, particularly due to inaccessible infrastructure. Additionally, non-deaf people generally do not know sign language, as it is not taught in schools. An entire deaf culture is reduced to an experience that can be bought, which alienates both the deaf guide and the non-deaf participants from the possibility of true relationality.

Figure 5. Set against a grey background, the figure displays visitor feedback written in black text. The comments include: “The greatest impediment is prejudice,” “Everything will be different from now on,” and “Empathy is the best way to understand others.” Image by the author.

Repoliticizing Disability in the Neoliberal Space-Time

Reducing identity to a game for the enjoyment of non-disabled participants exemplifies a neoliberal commodification of disability and the emotions of able-bodied people. Under neoliberal capitalism, as Harvey (2005) notes, everything—including identities, experiences, and emotions—is rendered as a commodity available for sale in the “here and now.” Both visits lasted only 1.5 hours, and this temporal limitation on the experience of disability, as framed by the museum, confines interactions and relationality to the immediate moment. This temporal restriction makes it challenging to extend the “empathy” emphasized by the museum creators, which, in practice, can reinforce hierarchical relationality, and makes it challenging as well as to foster solidarity beyond the spatiality of the museum. Additionally, the “happiness turn” in neoliberal societies (Ahmed 2010) has become a norm, pushing people to seek positive feelings for self-valuation. Able-bodied participants seek an activity to enjoy their “free time” on a Saturday evening and return home feeling good about their able-bodied status, having “experienced” disability for a few minutes, unaffected by infrastructural inequalities. The museum, therefore, reproduces ableism by providing a venue for this superficial engagement.

(Re)politicizing disability, however, may cultivate new values beyond neoliberal ones, such as interdependence, care, and respect for diverse ways of being and becoming in the world. To effectively (re)politicize disability, it is essential to incorporate a gendered perspective, particularly in Turkey, where the experience of disability is deeply influenced by gender. The intersection of gender and infrastructure uniquely shapes the everyday lives of disabled women, distinguishing their experiences from those of disabled men.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the participants in this project, which also received support from a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, and grants from the University of Arizona’s School of Anthropology as well as Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences. I also extend my thanks to Prof. Brian Silverstein, Dr. Ziya Kaya, Bedirhan Çetin, and the Platypus team for reviewing earlier drafts of this article.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Ziya Kaya.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The promise of happiness. Duke University Press.

Brenner, Neil, and Nik Theodore. 2002. “Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism.’’ Antipode 34 (3): 349-379.

Collier, Stephen. 2005. “The spatial forms and social norms of ‘actually existing neoliberalism’: toward substantive analytics.’’ International Affairs Working Paper, 4.

Connell, Raewyn. 2011. “Southern bodies and disability: Re-thinking concepts.’’ Third World Quarterly 32(8): 1369-1381.

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ.

Kafer, Alison. 2013. Feminist, queer, crip. Indiana University Press.

Scott, Joan W. 1991. “The evidence of experience.’’ Critical inquiry 17 (4): 773-797.