Publishing is confusing and complicated. There are often barriers to understanding it fully. And the process is very rarely fully transparent. So, I’m sharing my experiences of the publishing process, how I got my agent, and discuss whether or not academics need agents. “Do Academics Need Agents?” is Part 1 of a series on publishing in academia. In Part 2 of this series, I talk about why I, as a PhD student in STS, chose to go with a trade publisher over an academic one when my book went to auction.

I spent the COVID-19 pandemic buried deep in “the querying trenches.” Querying is the first stage of the publishing process. After a manuscript or book proposal is complete, an author submits to literary agents, via querying, in the hope that they might gain representation. This process is extensive and can often take months if not years with little reward. Websites like Querytracker, Querymanager, and Publisher’s Marketplace have been designed to assist with querying and make the process more transparent, allowing authors to see data on queries and sales, though less than one percent of authors will go on to be represented.

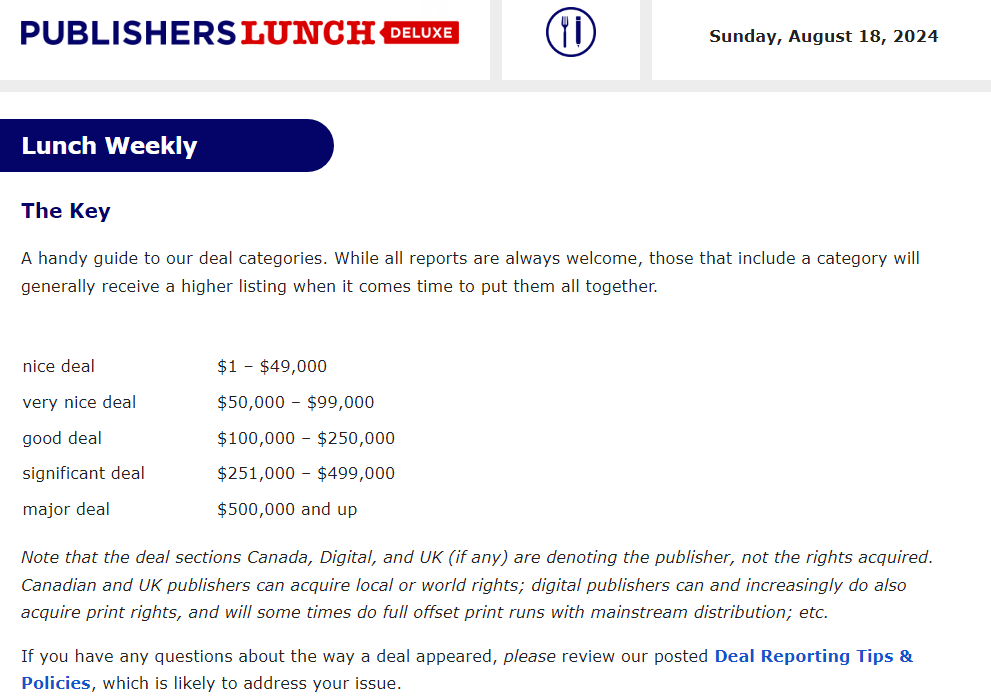

In its earliest stages, the publishing process is time consuming and confusing. Even with the help of websites such as these, as I queried agents I was met with paywalls, non-specific data, coded language, and industry-specific information that was difficult to understand. Years later, as a now-published author, I still require the help of my agent to understand the niche complexities of the publishing process.

Most academics will never engage with an agent, and if you’re asking yourself as an academic, Do I need an agent?, the simple answer is no—not if you intend on only publishing with academic presses, such as MIT Press, Yale University Press, Berkeley University Press, etc. You also don’t need an agent if your primary motivations for publication are academic. However, if you hope to someday publish with a trade press such as Penguin, Harper Collins, or Simon & Schuster, or are interested in having stronger public representation for your work or developing your research in a more commercial style, you’ll need to acquire an agent.

An agent’s role is to act as a mediator and negotiator between publisher and author. They assist with early editing and negotiations throughout processing, and most importantly, help an author sell their books to publishers. In exchange, they receive a percentage of sales from the author’s works and advances (typically around fifteen percent). Most trade publishers will not communicate with authors unless they have an agent, while academic publishers will often communicate with authors who are unrepresented.

Whether or not you need an agent as an academic is ultimately a question of how firmly your career falls within the realm of academia, the audience you hope to reach, and the style in which your nonfiction research is written.

…

I stared at James’s latest revisions of our proposal for Ground Control: An Argument for the End of Human Space Exploration, grumbled lightly to myself, and then set to work writing a new sample chapter. Printed out in a stack on the table beside me was a borrowed copy of a colleague’s book proposal to use as reference material. Fiction authors might have to write entire books prior to submitting to an agent, but nobody warned me that as a non-fiction author I would one day be neck deep in a hundred-page book proposal.

I met James McGowan, my agent, by accident. That doesn’t mean I wasn’t looking for an agent. Like I said, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, I was deep in the querying trenches. Between the years of 2014 (when I was eighteen) and 2021, I had been submitting my fiction manuscripts to agents non-stop. Writing had always been a serious part of my life and by the time I met James in 2021, I had a drawer full of completed novels that had been rejected many times over. In 2021, and the years prior, I wanted an agent because I wanted to be a fiction author. The prospect that I would become a non-fiction author, and have my academic work represented, was not one I seriously considered.

Some academics seek out an agent to represent research they know is meant for audiences beyond academia, while others might have an agent approach them for an academic book that is selling particularly well. My “how I got my agent” story exists on the fringes of these stories. James McGowan and his colleague at BookEnds Literary Agency, Jessica Faust, co-host a popular Youtube show on publishing processes. In my spare time, as a way of decompressing, I would watch the show while I cooked or did chores around the house, always interested in learning more about the industry. The co-hosts were approachable and often answered comments sent to them by viewers, so one day, setting nerves aside, I emailed Jessica for advice on my fiction manuscripts, but mentioned I had also written several articles and blog posts about space ethics related to my ethnographic research at Spaceport America. Rather than give me advice, Jessica wrote back immediately and introduced me to James.

Screenshot from the BookEnds Literary Agency Youtube Channel.

Did it make sense for me as an academic—hoping to stay in academia —to have an agent? Yes, because even though I aimed to work in academia, my research tended to move beyond academic audiences. Also, stylistically, the tone of my work was often more commercial than theoretical. Additionally, I hoped to one day be represented for my fiction and non-fiction. Because of this, acquiring an agent made sense for me.

By the end of autumn James had taken me on as his client and by the turn of the new year James and I went on submission with our proposal for Ground Control: An Argument for the End of Human Space Exploration. “Submission” meant that James took our seventy-two-page proposal, created a pitch for it, and sent it off to a “round” of about fifteen editors at various publishing companies. The editors would read the proposal and if they liked it, they would take the proposal to their acquisitions board and convince a whole slew of people why they should “buy” my book. We expected to hear back from them in about six to ten weeks.

The Publishers Marketplace key for understanding language used in sales announcements.

Submission was as exciting as it was grueling. We waited. We got rejections. We got in-depth feedback. Round one came and went with no luck, and I ticked off names of editors on my tracking sheet with a bright red marker. After round one ended, we edited our proposal, James created a new list, and by March of 2021 we went out on another round of submission. Within academic publishing, I had seen book proposals as short as five pages, but we intended to submit to both academic and trade publishers so our proposal included components beyond just a summary of the project. Our second round of submission included more medium sized presses, as well as some academic ones, and the feedback we heard back was more positive. About half of the publishers showed excitement for the book and took it to their board, but unfortunately we didn’t make it past acquisitions.

After the second round of rejections, I felt disheartened. But James, had (has!) so much faith in my work. The fact that so many editors took the book to their acquisitions team was a great sign. Of course, we would resubmit, and with very little edits to the proposal this time. With summer just around the corner, we went on a final round of submission. Our final pool of publishers included a wide range of large companies, indie presses, and academic presses.

We quickly got two offers.

…

I’ll save my conversation for why we went with the publisher we did for Part 2 of this series, but in the spring of 2022 we sold Ground Control to Chicago Review Press. Chicago Review Press had a vision for my book that very much matched my own. They had an impressive marketing plan. They offered me great royalties, retention of certain rights, and an advance of just under $10,000. And I could not have done it without James. But as an academic can you publish without an agent?

Yes!

And most academics will publish without an agent. Representation should work to your benefit and your agent’s. Most academics don’t need an agent because they intend to work primarily with academic presses and publish primarily for academic audiences. But if you’re an academic who hopes to reach a wider audience or enjoys writing in a more commercial style, then you might consider readying yourself for the querying trenches so you have access to a wider range of publishers and stronger marketing plans. That being said, more and more combination trade/academic presses are emerging that blur the lines between both worlds. Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series to learn more about trade versus academic presses.

1 Comment

Thanks for the tips! I’m working on my second book and the industry has undergone a revolution since my last one… Plus anyone that combines space, anthropology, and D &D (I’m currently a Warlock bound to Dendar the Night Serpent) is worth learning from!