Every Thursday at 9 o’ clock in the morning, housewives from a residential neighborhood on the outskirt of Jakarta gather at their usual spot at the “Love Earth” waste bank (bank sampah).[1] It is a small lot in the corner with a humble setup with a hut, a shed, and sacks of recyclables. Whoever arrives first begins sweeping the area and wiping the table, often damp from the last night’s rain and scattered with fallen leaves. One after the other, more women trickle in, each carrying a bag of recyclable waste from their households on foot, on motorcycles, or, more rarely, in cars. At times, items left by their neighbors—bundles of empty water gallons, piles of flattened cardboard boxes, or bottles of used cooking oil—wait to be weighed and sorted. The volume and the types of recyclables gathered each week may vary; yet food, tea, and chatter are invariably shared among those present.

Love Earth waste bank, like many others, comes into its most visible form in its weekly collection, sorting, and documentation of waste. In examining the financialization of recycling and the making of urban community, as particularly experienced by women, waste banks have become key sites for my research. Common narratives around waste banks position the idea of ‘community’ on the assumed linear trajectory of waste that it facilitates recycling from households (“source”) and thus diverts waste from landfills (“end”). In this essay, I explore the possibility of viewing recycling as a space of women’s labor, ethics, and livelihood, the dimension often falls outside the scope of this blueprint.

Figure 1. A fieldnote sketch from a morning at a waste bank. Clockwise: ‘Most common plastic beverage bottles,’ ‘Clean knob,’ ‘Cutting the chicken,’ ‘Coffee left by a guest last night,’ ‘Waste bank savings book,’ and ‘Weighing the waste.’

Banking on Waste

In recent years, waste banks in Indonesia have gained traction as a community-driven recycling initiative. Customers of these banks, typically individual households or groups of immediate neighbors, deposit the monetary value of their recyclables which are then sold to intermediaries. The government of Jakarta, among other municipalities, aspiringly mandates one or more waste bank per Rukun Warga, the second lowest administrative units. There is an unequivocally paternalistic discourse, echoed by the government, media, and academics. In this view, as exemplified in a recent article, a waste bank is where “orderly, disciplined, cooperative, and actively participating residents” are rewarded with “economic benefits and incentives” (translated by author) (Sasoko, 2022, p. 22). Yet, anthropological accounts of waste banks offer a more critical take, flagging a familiar usage of moral ideologies underpinning the New Order developmentalist state. Schlehe and Yulianto (2020) observe gotong royong, the Javanese ethos of non-monetized reciprocal assistance—a tradition often invoked to justify the mobilization of village labor (Bowen, 1986)—serves as an ideological resource. Pakasi et al. (2024) argue that ibuism, which incorporates women into the state developmentalist project through their expected role in creating healthy family and household, remains central in the recent feminization of environmental responsibility (Suryakusuma, 2011). Indeed, these ideological apparatuses seem instrumental in addressing a contemporary crisis: the ‘waste emergency (darurat sampah),’ as expressed by the current Prabowo administration, that has grown chronic in its cities (Yaputra, 2025).

Whether celebratory or critical, these voices tend to take the significance of waste banks granted. The sentiment I encountered in the field, however, told a different story. Some were puzzled by my interest in waste banks. Environmental activists and industry professionals were hesitant to view them more than “housewives’ plaything (main-mainan).” The quantity of waste banks’ contribution to handling household waste pale in comparison to that of the informal waste pickers. Meanwhile, the members of waste banks themselves often describe their activity as “just social (sosial),” implying its communal nature is predicated on the absence of economic aspirations. This essay is an attempt to create a generative interval between them—one that pauses before settling into any singular narrative, allowing the complexity of waste bank practices to surface. In ethnographic observations at the Love Earth waste bank, I tried to achieve this by describing the nuanced details of their daily practices.

The Vernacular of Sorting

A core group of six women in their 50s and 60s are staff members as well as the most enthusiastic customers at the Love Earth waste bank. Their tasks include weighing the recyclables; documenting the types, weights, and prices of these items in various forms; sorting and managing the recyclables; and handling the business relations with waste traders. During my visits, they began weighing and sorting work only after sharing food and conversations. Interestingly, even in basic sorting for recycling, materials are rarely referred to as “waste.” Customers sort their waste at home before bringing it to the waste bank where the core members further sort the recyclables, breaking down materials, literally and figuratively, into even more specific categories. The distinction of two levels of sorting is embedded in local terminology. General sorting (pilah) is conducted at the household level, where broad material categories (e.g., plastic, paper) are separated; detailed sorting (sortir) is carried out at the waste bank, where materials are subdivided into specific types (e.g., different grades of plastic). This distinction between pilah and sortir might appear an everyday linguistic convention. Yet, within the waste bank, this distinction reflects an assertion of its role in recycling, positioned between households and industry, with their technical expertise and labor.

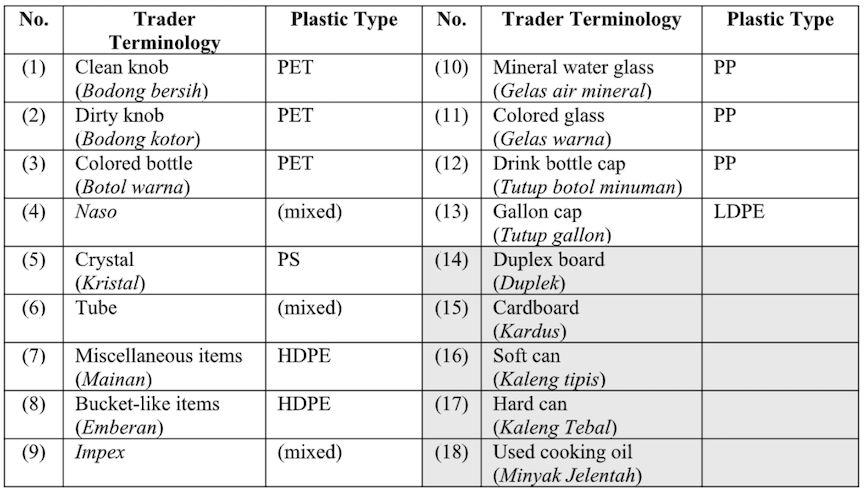

As I participated in sorting work and asking the staff members to teach me, I began to notice how the classification of materials is deeply tied to industry-specific terminology. Dewi, the founder and the current leader of the waste bank, described two distinct vocabularies: “waste trader’s vocabulary (bahasa pelapak)” and “plastic vocabulary (bahasa plastik).” The former refers to categories with different prices set by waste trader whereas the latter classifies materials based on plastic types, respectively represented in the columns in the table below.[2]

Figure 2. Categories of materials collected at the Love Earth waste bank.

These terminologies encode the level of labor applied in sorting and the price of its outcome. For instance, (1) and (2) from the table above are PET bottles for water and soft drinks are priced differently depending on their condition. “Clean knob” (bodong bersih) refers to a PET bottle with its label and cap removed, which is priced higher than “dirty knob,” (bodong kotor) bottles with label and cap remain attached. “Clean” (bersih) status refers to categorical purity—whether the bottle has been fully separated into its correct material type—than contamination by, such as, leftover liquids.

Similarly, “mineral water glass,” (gelas air mineral), a 220ml cup often served to guests at events, can be sorted further by removing the plastic lid, which increases their price. However, as this removal process is much more strenuous, requiring a knife, the workers at the waste bank have opted not to separate it—hence, this distinction does not appear in the categories I outlined earlier. As such, what falls outside these classifications remains as significant as what gets sorted. Items that middlemen refuse to buy—such as plastic sachets or the lids removed from gelas—become concerns for these women as they must decide what to do with what remains. Often, this residual waste is either burned or repurposed into handicrafts. This illustration, albeit cursory, suggests how sorting unfolds in practice at the waste bank. While following the middleman’s classification, it also lends itself to embodied knowledge of differentiation, the availability of tools and infrastructure, and economic incentives.

Beyond the Bin: Women’s Networks of Work and Care

Figure 3. A snapshot from the weekly staple-giving event. 80 to 100 bags of groceries are distributed weekly. Each bag is valued at around IDR 15,000 (approximately USD 0.94).

“Maybe she forgot her own self (lupa diri). We eat together, and whatever is left, we share it equally (rata-rata). Not all to yourself.”

It was at a weekly staple-giving event, Jumat Berkah, when Lilis let slip her complaint over a customer at the waste bank. Lilis is among the core members at the waste bank who also join this charity activity every Friday, where staple groceries donated by the neighbors, such as cooking oil, rice, instant noodles, and eggs, are distributed to those in need. Amid the chatter following the event, gossip lingered over the behavior of a waste bank customer, Sri, their fellow neighbor. In the previous weekly waste bank activity, while the others were preoccupied with the sorting, Sri ate all the remaining cookies shared among everyone present. In their grumble, the unwritten ethics were explicitly registered to me for the first time: not only should food be shared, but any leftovers, too, must be distributed as equitably as possible. This incident directed my attention to the practices at the waste bank that were seemingly irrelevant to recycling. It might seem like an incidental episode or expression of an unmet expectation that equal contribution should be met with equal distribution. Situated in the broader web of economic exchanges among these women, however, it appears more than a mere coincidence.

I see this as indicative of how the waste bank blurs the line between making money and caregiving, as illustrated by the way saving accounts are managed. Most active savings accounts operate at the immediate neighborhood level, with modest profits distributed for various circumstances, such illness in the family or gift-giving during Ramadhan. Alongside providing care work for their household members, women who are the core members often piece together income from various sources for supporting each other and beyond. Food is the key medium through which aid extends beyond waste bank and even beyond their residential complex. It was the core members that initiated the Friday charity event distributing staples to less privileged neighbors and waste pickers living outside the complex. Similarly, the proposal for a micro-business, a food stall selling take-away meals on a commission basis (jas titip), were brewed during these “food and tea hours” at the waste bank. “We are always meeting often chatting at the waste bank,” to quote Dewi again, “then we were like, ‘Let’s not just be idling around (iseng-iseng).’” They soon realized other women in the neighborhood were interested in providing food for donation or a food stall. Despite their apparent dismissal of these moments as idle time, it provided openings where these housewives carve out greater foothold in the household economy so that they wouldn’t remain ‘silent (diam)’ or solely dependent on their husbands for cash.

Waste banks, in what I would heuristically call developmentalist and environmentalist perspectives, take on the role of diverting the household waste from landfills. This portrayal of the initiative echoes a familiar archetype in Indonesia: communities as morally cohesive and self-regulating units, seamlessly integrated into the state—an idea often reflected in how participants themselves speak about waste banks. Yet, the processes of establishing and operating waste banks that foreground community participation, particularly by women, might appear differently if viewed through how they engage in loose yet vital economic ties in the neighborhood. A wordplay I came across in the fieldwork humorously encapsulates this: “It is not a waste bin (bak sampah). It is a waste bank (bank sampah).” More than a pun, this contrasting imagery between the bin and the bank, hints at alternative trajectories of waste that do not fit neatly into the dominant narratives. Instead of waste passively accumulating in a bin, ‘banking’ transforms it into a currency in economic and ethical networks between these women. My observation at the Love Earth waste bank suggests how this transformation could take shape.

Notes

[1] All proper names appear in this essay are pseudonyms except for public figures.

[2] The classification presented in this table is based on the author’s observations and interviews with the staff members at the waste bank.

References

Bowen, J. R. (1986). On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Studies, 45(3), 545–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/2056530

Long, N. J. (2022). Afterlives and Alter-lives: How Competitions Produce (Neoliberal?) Subjects in Indonesia. Social Analysis, 66(4), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2022.660406

Pakasi, D. T., Hardon, A., & Hidayana, I. M. (2024). Gendered community-based waste management and the feminization of environmental responsibility in Gr. Gender, Technology and Development.

Schlehe, J., & Yulianto, V. I. (2020). An Anthropology of Waste: Morality and Social Mobilisation in Java. Indonesia and the Malay World, 48(140), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2019.1654225

Suryakusuma, J. I. (2011). State Ibuism: The Social Construction of Womanhood in New Order Indonesia. Komunitas Bambu.

Yaputra, H. (2025, March 12). Darurat Sampah, Presiden Prabowo Panggil Menko AHY dan Menteri PU Dody. Tempo. https://www.tempo.co/politik/darurat-sampah-presiden-prabowo-panggil-menko-ahy-dan-menteri-pu-dody-1218664

Acknowledgements

This piece was written in English by Jiwon Kim, and translated into Bahasa Indonesia by Muhammad Fahmi Ilyas. This post was curated by Contributing Editor Soojin Kim.