The tension between binary thinking and the fluidity of identity has long been featured in discussions of definition in computational practice within galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. Nowhere is this more evident than in how data systems attempt to categorize — or fail to categorize — 2SLGBTQIA+ subjects. Metadata schemas, survey tools, and classification structures often rely on rigid dichotomies, such as male/female, known/unknown, or 1/0.

Notably, scholars have been critical of how the Library of Congress structures its Machine-Readable Cataloging (MARC) system, which is standard across universities in North America. This powerful cataloging tool emerged from the Library of Congress, specifically only having three gender options: male, female, and not known (375 – Gender (R), n.d.; Cole et al., 2013; Seikel & Steele, 2011). These dichotomies obscure lived realities and produce NULL values — the absence or unreadability of data — whenever individuals cannot or will not be slotted neatly into a recognized category —or the people entering the data are uncomfortable making a decision. Yet the resistance to classification is neither a failure nor a void; as scholars such as Jacob Gaboury (2018) have argued, NULL values can open a space for reimagining the relational possibilities of data. Despite its challenges, this paper explores how Linked Data — a system of semantically structuring a set of relationships rather than rigid definitions within taxonomies — provides a conceptual framework to address these issues. Moving away from binary inputs and outputs, Linked Data can help represent a spectrum of approximations, identities, and relational shifts—an approach that, although more complex, more accurately reflects the reality of fluid and evolving identities.

Null Values and the Limits of Binary Systems

NULL values are typically treated as blank or empty fields in data sets, whether in MARC records, SQL databases, or standardized demographic surveys. In conventional computing or cataloguing, a NULL entry is seen as a failure to capture the necessary information. Yet, as Gaboury’s (2018) notion of Becoming NULL reveals, this empty space can be meaningful — it marks where people are rejecting the system. For many queer individuals, the impetus to check a single box — be it male, female, or even not known— rests on faulty assumptions about what identity means. A NULL response may signal that none of the available fields actually describe that individual or that the question itself is misguided.

From a technical standpoint, binary logic underlies many of our cultural conceptions of computing. People often interpret digital devices as purely binary — just ones and zeroes — when, in fact, these numbers are symbols for more complex underlying physical and logical networks. This simplification has social consequences; if the system is built on a one-or-zero approach, it implicitly pressures identities into a parallel binary. In data practice, the easiest path has often been to slot individuals into predetermined categories. However, this approach risks misrepresenting or erasing entire ways of being. However, the complexity of generating a system around more complex configurations runs yet another risk: overcomplicating identity. Sari van Anders (2015), for example, has built a complex system for creating more definitions around the ambiguities of identity through a Sexual Configuration Theory. However, this theory requires a rule book and a guide and is primarily focused on clinical psychology, raising the question, “How do we operationalize ambiguity in computational systems?”

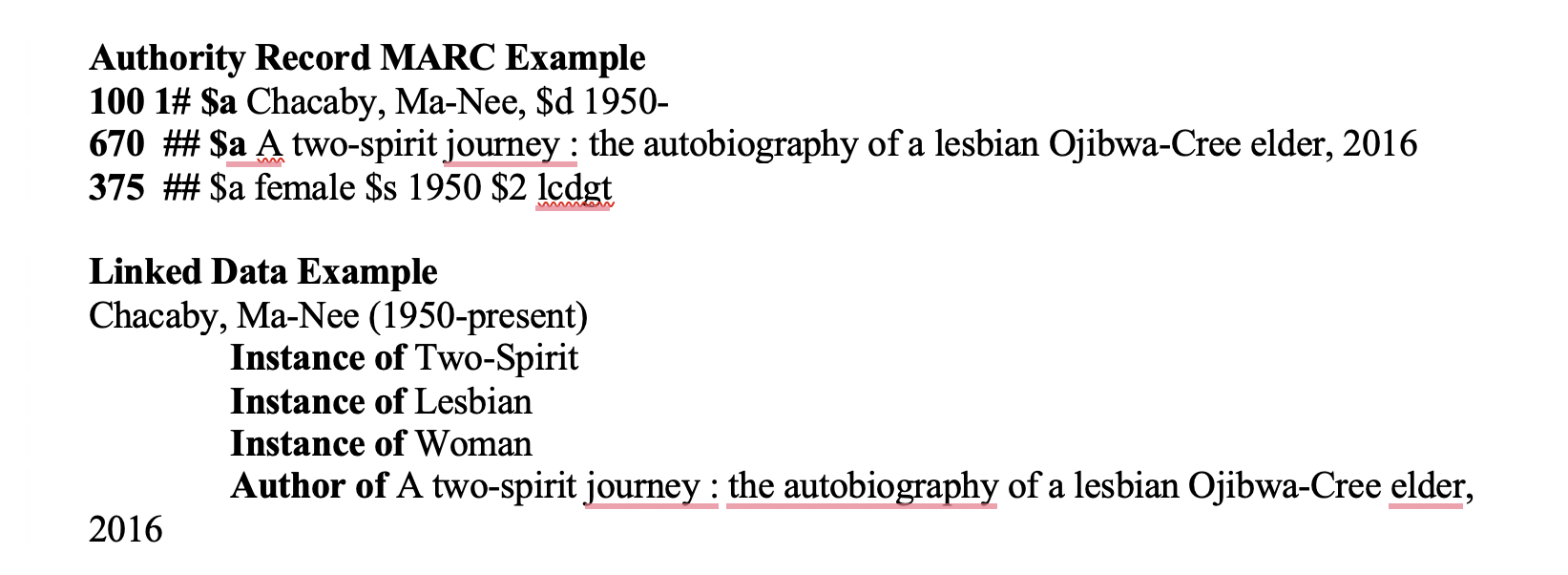

Illustrative example of a traditional data structure (MARC) and relational Linked Data

Shifting Identities and Epistemologies of the Closet

The problem of fixed labels becomes even more pronounced once we consider that identities are not static. Eve Sedgwick (2008), in Epistemology of the Closet, argued that identity — particularly sexual identity —exists in tension between disclosure and concealment. Identities shift across contexts, carry different meanings in diverse spaces, and may transform relationships over time, making them notoriously difficult to define (Beischel et al., 2023). This observation is especially relevant to communities such as the Two Spirit of Turtle Island, whose identities often cannot be captured by a single marker like gender or sexual orientation. Being Two Spirit, for instance, is intimately tied to Indigeneity and spiritual or community connections, and it may overlap with trans or non-binary experiences (Wilson, 2008). A purely binary data system, or one that only expands the list of discrete categories, fails to account for the possibility of movement along multiple axes of identity.

Linking Data to Embrace Complexity

Linked Data offers a potential solution — or a more nuanced conceptual strategy. Rather than forcing data into hierarchical fields, Linked Data models (such as those employed in Wikidata) form a web of relationships between entities. In these models, the node representing a person can have any number of semantic connections or active relationships, pointing to information about language, culture, affiliations, experiences, and identity descriptors. This flexibility recognizes that identities cannot always be pinned to a single, stable property.

That said, Linked Data is not a panacea. Critics might argue that it can become messy, creating a vast web of relationships that is challenging to maintain due to its semantic nature rather than being structured through controlled vocabularies (Dimou et al., 2017; Oldman et al., 2015). From a purely practical perspective, large-scale Linked Data systems require ongoing curation, clarity, and governance — factors that become even more complicated when the data involves personal or intimate attributes such as gender and sexuality. Another consideration is whether individuals want to publicly link these pieces of information about themselves or have the capacity to do so. Where does privacy fit in? How do we protect individuals from unwanted exposure, especially when identity is private and situational?

Furthermore, like all data structures, Linked Data carries assumptions about who defines the relationships, how they are validated, and whose knowledge paradigms are reflected. Nonetheless, its relational framework better accommodates the idea that a single individual may appear as a node that changes over time or whose relationships with other entities evolve. It can also include ways to express no value or unknown that may be more sensitive to the complexities of identity instead of treating those states as mere gaps.

The Politics of Data Gathering and Usage

Another crucial question is: Why is this data collected, and how will it be used? I myself am Indigi-Queer and work with other Indigi-Queer Two-Spirit Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and scholars, and this results in gender and sexuality data that is unreadable by systems because it hugs multiple genders and sexualities if we attempt to fit it within Western data perspectives. Consequently, modern institutions often request sensitive information from me and my participants that is confusing and disrespectful — not honouring our lives and identities — when they attempt to gather data on equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) through rigid and structured taxonomies of who is considered diverse. Moreover, the questions that are asked in forms are often confusing because they exclude the possibility of Two-Spirit identity by hiding it under sexuality or gender when it could be both or neither since it is a fluid identity that is rooted in practices based on individual Indigenous communities.

The categories in the EDI forms fall short of capturing the complexities that participants bring because, often, the goal is not to honour identities but to sidestep structural racism by creating data demonstrating that an organization is diverse. This is often done to signal surface-level change, such as highlighting how multicultural an organization is, rather than addressing the deeper systemic issues and confronting historical injustices (Berrey, 2015). Ultimately, where does Two Spirit fit? Is it a gender category, a spiritual category, or something else entirely? Suppose a data-collection method lumps Two Spirit under sexual orientation. In that case, that choice might be perceived as invalidating or disrespectful, conflating a culturally specific identity with categories primarily designed for Western constructs of sexuality.

Linked Data’s approach addresses part of this concern by encouraging the creation of multiple, interlinked descriptors instead of single fields. Effectively, this system proposes creating semantic links that help to describe an identity from different perspectives, narrowing down the axis of identity and establishing a range of identities possible within a semantic set of boundaries: an x and y axis of possibility. In this re-framing of data, people’s identities and community relationships act similar to particles—oscillating between values depending on how their community, gender, and sexuality contexts are being activated.

However, this approach demands careful ethical consideration. Who decides on the categories or the ways they interlink? How do you protect sensitive data once it is linked? Does the system allow for degrees of anonymity, or can data expire or shift as a person’s identity changes? These questions must be negotiated with the individuals whose data is being recorded.

Conclusion: Embracing Ambiguity as Accuracy

Acknowledging shifting identities and embracing NULL values complicates data analysis but can ultimately produce more accurate and respectful records. A binary or fixed-category approach simplifies the rich tapestry of human experience into simplistic and often exclusive boxes. With its ability to weave intricate relationships, Linked Data offers promise as a conceptual (though not uncomplicated) framework for representing how identities truly function in context.

Far from being an admission of lack, NULL values and shifting fields can mark a space of possibility. They remind us that identity is rarely a static declaration; as Sedgwick’s work underscores, it may remain in flux, varying from one environment to another. However, acknowledging ambiguity can be a step toward genuinely inclusive data practices, allowing for genealogies of becoming instead of rigid definitions. If we regard these relational networks with care — considering their ethical ramifications and the communities they serve —Linked Data might embody a more respectful and accurate mode of representation. Embracing that messy yet generative complexity is, in the end, not only more faithful to our lived realities but also a necessary move toward decolonizing and queering our data worlds.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Shreyasha Paudel.

References

375—Gender (R). (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 14, 2025, from https://www.loc.gov/marc/authority/ad375.html

Beischel, W. J., Schudson, Z. C., Hoskin, R. A., & Van Anders, S. M. (2023). The gender/sex 3×3: Measuring and categorizing gender/sex beyond binaries. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 10(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000558

Berrey, E. (2015). The engima of diversity: The language of race and the limits of racial justice. The University of Chicago Press.

Cole, T. W., Han, M.-J., Weathers, W. F., & Joyner, E. (2013). Library Marc Records Into Linked Open Data: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Library Metadata, 13(2–3), 163–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2013.826074

Dimou, A., Vahdati, S., Di Iorio, A., Lange, C., Verborgh, R., & Mannens, E. (2017). Challenges as enablers for high quality Linked Data: Insights from the Semantic Publishing Challenge. PeerJ Computer Science, 3, e105. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.105

Gaboury, J. (2018). Becoming NULL: Queer relations in the excluded middle. Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 28(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2018.1473986

Oldman, D., Doerr, M., & Gradmann, S. (2015). Zen and the Art of Linked Data: New Strategies for a Semantic Web of Humanist Knowledge. In S. Schreibman, R. Siemens, & J. Unsworth (Eds.), A New Companion to Digital Humanities (1st ed., pp. 251–273). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118680605.ch18

Sedgwick, E. K. (2008). Epistemology of the closet (Updated [ed.] with a new preface). University of California press.

Seikel, M., & Steele, T. (2011). How MARC Has Changed: The History of the Format and Its Forthcoming Relationship to RDA. Technical Services Quarterly, 28(3), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2011.574519

van Anders, S. M. (2015). Beyond Sexual Orientation: Integrating Gender/Sex and Diverse Sexualities via Sexual Configurations Theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(5), 1177–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0490-8

Wilson, A. (2008). N’tacimowin inna nah’: Our Coming In Stories. Canadian Woman Studies, 26(3/4), 193–199.