This post is part of a series on the SEEKCommons project; read the Introduction to the series to learn more.

Rene Gomez was one of the most renowned potato curators at the International Potato Center (CIP, Centro Internacional de la Papa in Spanish). [1] Potato curators provide reliable advice in safeguarding the CIP collection, carrying out key activities such as the acquisition, registration, cleaning, storage, regeneration, and distribution of seeds and other planting materials. Gomez’s 35-year journey with CIP left a remarkable legacy among potato conservation experts. I met him in February 2023 during my dissertation field work in Peru. I spent many hours listening to his life story, during which I learned how his work was connected to CIP’s history and research, about his dedication to his work, and about his concern for the future of potato curation. “We are an endangered species, us taxonomists and curators,” he mentioned. Gomez was worried about the precarity of the field, particularly the lack of young people who would continue his work after his retirement.

The unexpected passing of Gomez (April 19, 2024) left a void in the world of potato conservation and among those who knew him. I had been coding and reviewing the interview transcripts I recorded during my field work when I learned about his death. Many people that I interviewed mentioned Gomez in one way or another. A passionate advocate for potato biodiversity, Gomez dedicated his life to preserving the rich heritage of potato varieties, knowing that his work at CIP genebank supported Andean farmers’ livelihoods and promoted sustainable practices. His commitment to mentorship fostered a culture of collaboration, inspiring colleagues and mentees alike. Public comments on the In Memoriam Rene Gomez Facebook Page (April 24, 2024) attest to his impact on colleagues, friends and research collaborators.

Gomez’s death represents, in a way, the end of a generation of genebank scientists that prioritized knowledge production and community engagement. This generation included Carlos Ochoa, perhaps one of the more renowned Peruvian scientists, who conducted several expeditions to collect potato varieties from many regions of the Andes, including Chile and Bolivia. Both Gomez and Ochoa spoke Quechua, came from Cusco, and had their own private potato collections before joining CIP. They also faced similar challenges regarding the preservation of CIP’s collection during the 1980s, when guerrillas made difficult expeditions in the Andes (Spooner et al. 1999, Huaman & Schmiediche 1999). Gomez developed terms and methods that influenced CIP’s conservation approach, including “repatriation” and “dynamic conservation.” [2] Ochoa published editions of The Potatoes of South America on Bolivia (Ochoa 2004) and Peru (Ochoa 1990), which have become foundational works for potato conservation experts. Gomez and Ochoa trained the next generations of potato conservation experts, but, as I discuss below, the participatory research at CIP at times seemed uncertain and fragmented (Thiele et al. 2001), even though it is still a core component of CIP research programs.

Andean farmers are also experiencing a generational change, as older generations of farmers look to younger generations for marketing potatoes to new regional markets. Smallholders in Peru have protected Andean biodiversity for centuries, and Andean potatoes are intimately connected with Andean culture and religion (Yin 2016) and have nutritional qualities that make them the basis of Andean diet (De Haan 2019). Most potatoes have Quechua names that represent the dynamic way Andean farmers interact with them, since the names represent customs, farming tools, local fauna and flora. During my field work, I observed how farmers have expanded the diversity of potato products through marketing to urban consumers, high-end restaurants, and food processing companies. At regional and national food fairs, potatoes are sold in the form of vodka, chips, and tubers. The Peruvian gastronomic boom has led to the promotion of Andean foods in different markets (Matta 2014, Garcia 2021), and projects focusing on rural infrastructure, the expansion of supermarkets, fostering strong relationships between producers and the urban gastronomic sector have contributed to this growth (Campos and Ortiz 2020).

While potato farmers have been referred to as “guardians” of agrobiodiversity in this context (Huanay 2023), little attention has been paid to the precarity of this continuing guardianship. The lack of youth and women farmers present at annual meetings and events puts into question who will be the agrodiversity guardians when the older generations of potato farmers pass on. In this post, I assess the future uncertainty of potato agrobiodiversity by exploring CIP’s participatory research and engagement, as well as the interaction between ex situ (lab) and in situ (farm) conservation.

Conservation Assemblages: Participatory Research, Ex Situ and In Situ Andean Potato Conservation

For more than 50 years, CIP has been working alongside custodian farmers to increase potato agrobiodiversity conservation. Founded in 1971 as a research-for-development center, CIP is part of the CGIAR network, a global partnership of research centers that focus on subsistence crops such as corn, rice, and sweet potato. CIP provides plant genetic material to farmers, and researchers based in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. CIP’s research resonates beyond Peru, and farmers from neighboring countries have come to Peru to learn about conservation practices. Interactions among potato farmers, researchers, technicians, government agencies have shaped the potato value chain in Peru, due to promotional initiatives such as the International Potato Day (Ordinola 2023). With the development of strategies to improve smallholders’ access to markets, to include farmers in research, and to conduct nutrition related research (Ortiz et al. 2020), CIP has diversified its participatory research portfolio.

Gomez’s community-engaged work shaped CIP’s potato collection conservation and distribution protocols. Fluent in Quechua, Gomez conducted workshops with potato farmers from the Potato Park in Cusco, a conservation area dedicated to preserving the genetic diversity of Andean potatoes that was established in collaboration with Quechua Indigenous communities. These workshops were designed to help farmers reintroduce varieties that had been lost in previous years. CIP’s reintroduction activities, undertaken through its repatriation program, aim to return varieties collected by scientists years ago to protect agrobiodiversity against environmental and social factors, such as climate change and political violence (Lüttringhaus et al. 2021, Ellis et al. 2020).

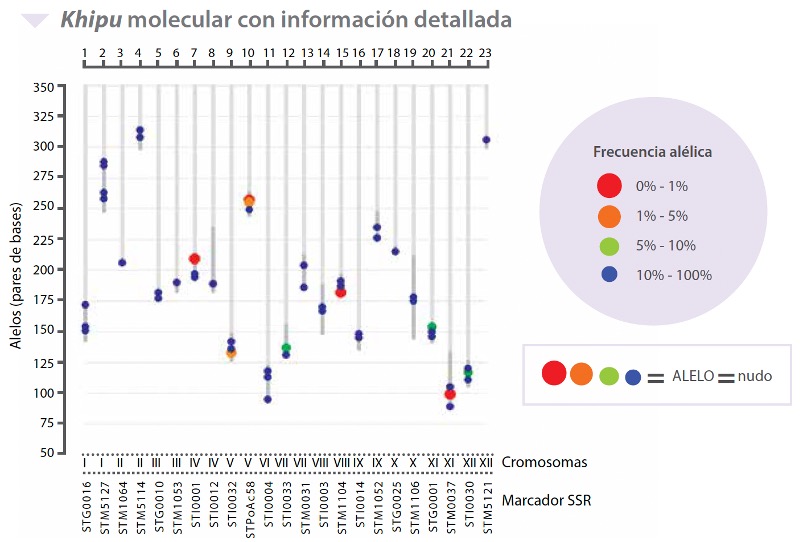

In order to communicate potato genetics to a non-scientific audience in the Andes, Gomez invented a tool that he called a “molecular quipu.” The tool represents plant genetics using the more culturally familiar form of the quipu, a recording device made from woven cords that has been used in the Andes for thousands of years. Gomez explained to me that the molecular quipu was intended to explain potato genetics to Quechua farmers and the public. Currently, it is featured in most regional potato agrobiodiversity catalogs, as a graphic that helps to explain each potato variety’s unique genetic traits. The molecular quipu is one example of participatory research developed by CIP staff and is the result of community engagement with Andean communities.

Molecular Quipu in Junin Potato Catalog. Source: Minagri et al. 2017. Catálogo de variedades de papa nativa del sureste del departamento de Junín – Perú. Lima (Perú). Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP).

Despite work by Gomez and others, in the past two decades, participatory research and community engagement at CIP had seemed at times fragmented and uncertain (Thiele et al. 2001). CIP is composed of many departments, among them CIP’s genebank, that receives, curates, preserves and distributes plant genetic material (CIP’s genebank website), and CIP’s Social and Nutritional Science Department, thay plays an important role in engaging policy makers, researchers, and the private sector with conservation. While it is not common for CIP’s genebank staff to interact with farmers, CIP’s Social and Nutritional Science Department staff conducts participatory research with farmers. Through the interviews during my field work, I learned that even though CIP’s genebank staff consider their work relevant for farmers, few of them had consistent interaction with them. However, CIP’s genebank plays a fundamental role in the distribution of pathogen free material to farming communities and food security. Since I started my fieldwork in 2022, I noticed a more active involvement of CIP’s genebank staff in farmers meetings and biodiversity monitoring activities, traveling with them outside Lima. Before I started my field work, CIP’s genebank staff played an important role in a biodiversity monitoring project that included interacting with farmers from Pasco and Sierra de Lima to identify gaps in CIP’s potato collection (CIP 2021).

AGUAPAN 10th Annual Meeting in Paucartambo, Cusco. 5 August 2024. Image by author.

While collaboration between genebank scientists and farmers seems to be strengthening, the uncertainty of potato farming’s future is rising. While the gastronomic boom of potato products is celebrated (Matta 2014, Garcia 2021, few discussions have emerged about potato production as a precarious and a labor-demanding process (Scott 2011, De Haan 2009, Tobin et al. 2016). The current lack of youth and women farmers in decision making is likely a consequence of years of men having leading roles in conservation, agriculture and household decisions. AGUAPAN, a national association of potato guardians, has attempted to engage younger generations in conservation. It also elected its first woman president in July 2024. Yet, the majority of the board members are older men. The farmers that I met and interviewed were all at least 50 years old and all were men. Through participant observation and interviews in Cusco, La Libertad, Huancayo, and Lima, I learned that it is not clear if rural youth are willing to do the same work as their parents, or if, instead, young farmers are willing to support their parents in other ways, such as commercialization in food fairs. Based on participant observation during potato guardian annual meetings, young farmers seem to be leaning towards commercialization and marketing activities.

CIP staff, agriculturalists, and conservation experts at the Native Potato Festival in Lima. 26-28 May 2023. Image by author.

In the case of potato conservation, farmers and curators are actors in knowledge infrastructures consisting of research facilities, regional potato catalogs, and digital platforms such as biodiversity apps. Knowledge infrastructures remain invisible or taken for granted until they are examined from within (Edwards 2010, Hine 2020). Science and technology studies (STS) scholars have used the term invisible labor in science to signal the role of experts that sustain knowledge infrastructures (Bangham et al. 2022). As actors in Andean conservation infrastructures, potato farmers and curators at CIP’s genebank tend to remain invisible, even though their labor is complementary and sustains potato agrobiodiversity. Currently, farmers and CIP staff collaborate well, despite moments of uncertainty due to project decision making and funding as I observed during my field work.

Indigenous scholars have used the term Indigenous science to value the knowledge systems of Indigenous and rural smallholder communities (Hernandez 2022, Bang et al. 2018). The recognition of Indigenous and community knowledge systems as Indigenous science builds knowledge bridges between western and nonwestern science. This is exemplified by the case of Andean potatoes, since Quechua culture is embedded in potato taxonomy. At the same time, the work of Rene Gomez reminds us that there are interesting cases when the opposite happens and western science can promote Indigenous scientific understandings. For example, as the result of rural community engagement and applied conservation, tools such as the molecular quipu are created by scientists in order to bring western and non-western knowledge into conversation. The next generation of potato conservationists—from CIP researchers to Indigenous and other smallholder potato farmers—needs to foster these ties as well as build the foundations for sustainable agroecological practices and Andean food heritage.

Footnotes

[1] CIP protects potato and Andean tubers that are in danger of disappearing or that are no longer available (Westengen et al. 2018). For example, since 1997, 89 farming communities have received over 6000 samples of cultivated potato from the CIP genebanks, comprising almost 30% of CIPs collection of native landraces (Gomez 2019).

[2] Potato repatriation and dynamic conservation are concepts used by potato conservation and agriculture experts. While repatriation involves the reintroduction of landraces to Andean rural communities, dynamic conservation refers to the interactions between in situ (farm) and ex situ(lab) conservation strategies and how both complement each other. For more information, please see: Lüttringhaus, S., et al. 2021.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Cydney Seigerman.

References

Bang, M, et al. 2018. If Indigenous Peoples Stand with the Sciences, Will Scientists Stand with Us?. Daedalus 2018; 147 (2): 148–159. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00498

Bangham, J., Chacko, X., & Kaplan, J. (Eds.). (2022). Invisible Labor in Modern Science. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Campos, H., & Ortiz, O. (Eds.). (2020). The Potato Crop: Its Agricultural, Nutritional and Social Contribution to Humankind. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3- 030-28683-5

CIP 2021. Monitoreo de la diversidad in situ y análisis de brechas genéticas de papas nativas en Perú para la conservación complementaria ex situ. Centro Internacional de la Papa.

De Haan, S. (2009). Potato diversity at height: Multiple dimensions of farmer-driven in-situ conservation in the Andes. Wageningen University.

De Haan, S., Burgos, G., Liria, R. et al. (2019). The Nutritional Contribution of Potato Varietal Diversity in Andean Food Systems: a Case Study. Am. J. Potato Res. 96, 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-018-09707-2

Edwards, P. (2010). A vast machine: Computer models, climate data, and the politics of global warming. MIT Press.

Ellis, D., Salas, A., Chavez, O., Gomez, R., Anglin, N. (2020). Ex Situ Conservation of Potato [SolanumSection Petota (Solanaceae)] Genetic Resources in Genebanks. In: Campos, H., Ortiz, O. (eds) The Potato Crop. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28683-5_4

Garcia, M. E. (2021). Gastropolitics and the Specter of Race: Stories of Capital, Culture, and Coloniality in Peru. University of California Press.

Gomez, R. 2019. Conservación dinámica de germoplasma. In situ y ex situ. Curso de Capacitación Manejo Integrado del Cultivo de Papa, 1-5 Abril, 2019. Lima (Peru): Centro Internacional de la Papa. 51 p.

Hernandez, J. 2022. Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes thorough Indigenous Science. North Atlantic Books.

Hine, C. (2020). Knowledge infrastructures for citizen science. In P. Hetland, P. Pierroux, & L. Esborg, A History of Participation in Museums and Archives (1st ed., pp. 93–108). Routledge.

Huamán, Z., Schmiediche, P. (1999). The potato genetic resources held in trust by the International Potato Center (CIP) in Peru. Potato Res 42, 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02358158

Huanay, J. et al. (2023). Red de semillas de AGUAPAN para la conservación de la agrobiodiversidad de papa frente a factores socioecológicos cambiantes. Colaboraciones para la agrobiodiversidad. LEISA. Vol 38, N2, pp 19-23.

Lüttringhaus, S., et al. (2021). Dynamic guardianship of potato landraces by Andean communities and the genebank of the International Potato Center. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience, 2(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-021-00065-4

Matta, R. (2014). República gastronómica y país de cocineros: Comida, política, medios y una nueva idea de nación para el Perú. Revista Colombiana de Antropología, 50(2), 15–40. https://doi.org/10.22380/2539472X45

Minagri et al. (2017). Catálogo de variedades de papa nativa del sureste del departamento de Junín – Perú. Lima (Perú). Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP).

Ochoa, C. (1990). The Potatoes of South America: Bolivia. The International Potato Center.

Ochoa, C. (2004). The Potatoes of South America: Peru. The International Potato Center.

Ordinola. (2023). Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas adoptó el proyecto presentado por Perú. Día Internacional de la Papa: 30 de Mayo. Agencia Agraria de Noticias.

Ortiz, O., Thiele, G., Nelson, R., Bentley, J.W. (2020). Participatory Research (PR) at CIP with Potato Farming Systems in the Andes: Evolution and Prospects. In: Campos, H., Ortiz, O. (eds) The Potato Crop. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28683-5_13

Scott, G. J. (2011). Plants, People, and the Conservation of Biodiversity of Potatoes in Peru. Natureza & Conservação, 9(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.4322/natcon.2011.003

Spooner, D.M., et al. (1999). Wild potato collecting expedition in Southern Peru (Departments of Apurímac, Arequipa, Cusco, Moquegua Puno, Tacna in 1998: Taxonomy and new genetic resources. Am. J. Pot Res 76, 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02853575

Thiele G, van de Fliert E, & Campilan D. (2001) What happened to participatory research at the International Potato Center? Agric Human Values 18:429–446

Tobin, D., Glenna, L., & Devaux, A. (2016). Pro-poor? Inclusion and exclusion in native potato value chains in the central highlands of Peru. Journal of Rural Studies, 46, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.002

Westengen, O. T., Skarbø, K., Mulesa, T. H., & Berg, T. (2018). Access to genes: Linkages between genebanks and farmers’ seed systems. Food Security, 10(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0751-6

Yin, S. (2016). Who First Farmed Potatoes? Archaeologists in Andes Find Evidence. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/19/science/potato-domestication-andes.html