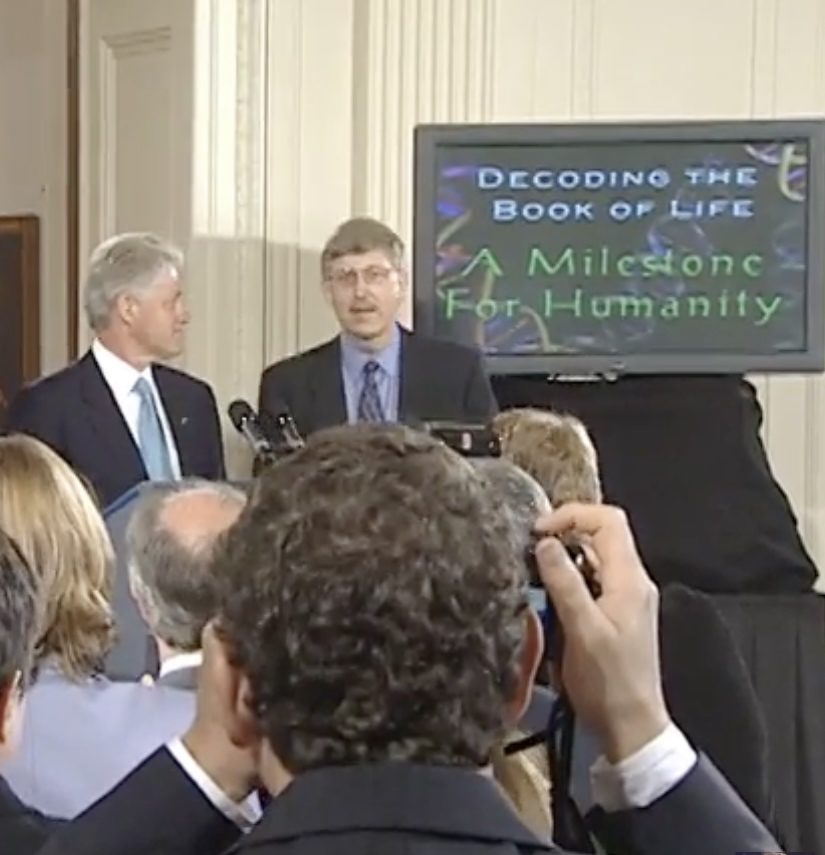

Next month marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first ever working draft of our species’ entire genetic code. It was a major milestone in the Human Genome Project (HGP), the ambitious international effort which began in 1990 and which remains one of the largest collaborative biology projects in history. The announcement was the subject of much fanfare, making the front page of the New York Times and the cover of TIME (headline: “Cracking the Code!”). In an offical ceremony marking the occasion, President Bill Clinton was joined in the East Room of the White House by NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins, the ambassadors of France, Germany, and Japan, and, via satellite, British Prime Minister Tony Blair. The President proudly summarized its top-line finding: race was indeed skin-deep, a trivial outer difference belying a profound biological sameness.

“… one of the great truths to emerge from this triumphant expedition inside the human genome is that in genetic terms, all human beings, regardless of race, are more than 99.9 percent the same. What that means is that modern science has confirmed what we first learned from ancient fates. The most important fact of life on this Earth is our common humanity. My greatest wish on this day for the ages is that this incandescent truth will always guide our actions as we continue to march forth in this, the greatest age of discovery ever known.”

Social morality had been validated at a molecular level with the tools of cutting-edge technoscience.

A High-Water Mark for the Subdiscipline

Encountering footage of this event as a new undergraduate anthropology student in the 2012-2013 schoolyear, the scene was not presented to me as a self-evident triumph of scientific and social progress. Instead, it was illustrative of a certain kind of complacent liberal scientism: 1990s colorblindness marked by a premature declaration of victory against racism, while failing to address the underlying material conditions. There were other trenchant critiques as well: this massively overpromised public expenditure had uncertain real-world applications to human health, but clear upside for the relatively small cadre of scientists involved. Writing in his 2012 essay on the state of capitalist innovation, “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit,” David Graeber singled out the HGP for this reason: “After spending almost three billion dollars and employing thousands of scientists and staff in five different countries, it has mainly served to establish that there isn’t very much to be learned from sequencing genes that’s of much use to anyone else” (Graeber 2012).

President Bill Clinton and NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins address a press pool during a ceremony at the White House. January 26, 2000. Image courtesy William J. Clinton Presidential Library.

Most notably, there was the question of that remaining 0.1%– the relentless focus of a “durable preoccupation with difference” (Pollock 2012) which used DNA to refashion a race science for the twenty-first century (Roberts 2012). Moreover, the entire affair lent authority to “genomic articulations of indigeneity” (Tallbear 2013)– a linking of racial identity to blood quantum via genetics with potentially calamitous implications for tribal belonging and anticolonial resistance. Under the guise of inclusion and diversity, the biological basis of race was being reified and reasserted (Fullwiley 2008; Montoya 2011).

Contemporaneous work coming out of the field armed me with powerful, sophisticated critiques. I cut my teeth in the classroom with these scholars, and my analytical framework is shaped in the image of their insights: about science as a site of culture, of competing interests, contested definitions, social meaning-making and the creation of discursive worlds with concrete impacts on peoples’ life-chances. My understanding of, and appreciation for, the anthropology of science and technology is inseparable from their contributions.

In retrospect, this intellectual moment was partly premised on the idea that the scientific enterprise was a mighty juggernaut– something that we in the interpretive social sciences could only hope to provide a running commentary for with the aim of steering it in a more just direction. It felt a little like an indestructible sparring partner, suitable for friendly intellectual roughhousing from the likes of philosopher-scientists like Donna Haraway and Karen Barad. But that reality is now seriously imperiled. The stability of the scientific enterprise – its public trust and support, its credibility and explanatory power, its role as a basic tool of governance and shared reality– is being significantly eroded. As science seemingly loses its epistemic monopoly, it becomes just another activity that some humans decide to get up to. Different modes of inquiry, whether lay Internet research, or highly credentialed professional science, are ‘flattened’ into different communities of roughly equivalent worthiness and explanatory value.

Towards the end of his life, Bruno Latour– a theoretical North Star for those of us engaged in the study of scientific knowledge-production – began to reckon publicly with how facticity ought to be treated in a ‘post-truth’ era. As he told the New York Times, “I think we were so happy to develop all this critique because we were so sure of the authority of science… and that the authority of science would be shared because there was a common world… Now we have people who no longer share the idea that there is a common world. And that of course changes everything” (Kofman 2018).

In recent years, asserting the ontological ‘realness’ of science has become a major fixture of liberal identity– and with good reason. Photo by author.

The intervening years have ushered in even more dramatic changes to the state of play of science and society, a metastasizing of Latour’s loss of a “common world.” The disturbing new contours of popular racial discourse serve as an instructive example: A media ecosystem of far-right “race realists” as likely to take an interest in craniometry as in genomics have shown that they do not need the velvet glove of liberal technoscience to wield the iron fist of white supremacy. A rotating cast of quack physicians and scientists are favorite thought leaders of rightwing ‘Zynternet’ podcasters and their audiences, who now seemingly set the agenda for popular discourse around health and medicine. Open white supremacists like Stephen Miller act as go-betweens, giving a direct line to the executive. Here, crowing from the ruling class that “the most important fact of life on this Earth is our common humanity” feels less like a spectacle of grotesque self-congratulation and more like a scene from some distant political horizon.

Covid Ends Science’s “Common World”

The Covid-19 pandemic was surely the greatest accelerant of this epistemic breakdown, an honest-to-goodness exogenous shock whose many unresolved questions remain the subject of both intense debate and numb repression. It spurred a spiritual and religious revival in the United States and accelerated deep distrust of medical-scientific authority. It saw QAnon go mainstream, syncretizing with new-age health movements and reaching vast numbers of the newly extremely online. Operation Warp Speed, arguably the singular achievement of the first Trump administration, has now been completely disappeared from public memory. Despite the vaccine’s success, more than half of all Americans who died of coronavirus did so under the presidency of Joe Biden. Positioning his administration as “following the science” while in fact prioritizing economic recovery, CDC director Dr. Rochelle Walensky rapidly slashed recommended isolation times, ignoring the agency’s own data about infectiousness (Jirmanus et al. 2024).

Pandemic upheaval also saw intellectual giants in the critical study of biomedicine fall from grace. Giorgio Agamben, whose critique of biology’s inherent authoritarianism has captivated students for decades (myself included), became an avowed antagonist of public health. Taking an extreme anti-lockdown position, he set alight his credibility as an expert on fascism, likening Zoom learning to concentration camps and the unvaccinated to Jews marked with Nazi ‘Juden’ stars (Bratton 2021). The physician-scientist Dr. John Ioannidis, whose landmark paper “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” (2005) garnered praise for drawing attention to the replicability crisis in science, made a similarly sharp fringe-ward turn. Once one of the most respected researchers in the world, Ioannidis published uncharacteristically flawed studies about the relative harmlessness of Covid-19, lending credence to the now-discredited “herd immunity” strategy (see Freedman 2020).

Along with fellow Stanford physician and “Covid contrarian” Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, Ioannidis sits on the editorial board of the newly founded Journal of the Academy of Public Health (JAPH)– a new kind of membership-based scientific outlet alarming mainstream scientists for its patina of respectability, lack of quality oversight, and preference for heterodoxy (see Offord 2025). This coincides with mainstream medical journals receiving threatening letters from DOJ attorneys about “competing viewpoints,” and is the clearest sign yet that the scientific enterprise no longer speaks with a univocal authority.

We have come full circle: As of April 1, 2025, Bhattacharya is the director of the National Institutes of Health. This is the same role once held by Dr. Francis Collins, prominently featured in that White House ceremony twenty-five years ago for his role in leading the Human Genome Project, and onetime target of anthropology classroom criticism. How much has changed since then: Collins, who recently stepped down from his longtime government post, now fears for his life amid the current political climate. Beyond individual animus, it is difficult to imagine any such massive international scientific cooperative happening today. Under the leadership of HHS secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., in coalition with evangelicals, vaccine and climate skeptics, and fringe scientists, the administrative state which has made American scientific progress possible since World War Two is being eviscerated. In short, “science has gone from being the bully to being the underdog” (Söderberg in Rommetveit 2021, 101).

Still “Against Health”?

Under such conditions, it becomes more difficult to neatly conceive of our anthropological work as being directed “up” at society’s most powerful institutions (Nader 1972; Gusterson 1997). Accordingly, I feel compelled to reevaluate my critical relationship to science. I am less comfortable taking an adversarial position– even a deeply sympathetic one– with regard to our colleagues in the hard sciences. It follows the same logic as insulting one’s siblings: it’s okay if I do it, because I know I have their best interests at heart.

Should we refrain from kicking science when it is down? Ought the level of our critique be calibrated to how vulnerable the scientific enterprise is in a given moment? Would we dare release a book called Against Health (Metzl & Kirkland 2010) in 2025, when being against health seems to explicitly be the order of the day? And how do we speak honestly about how much worse things have gotten without rehabilitating the tepid liberalism which got us here in the first place?

Back in my first ever anthropology classroom, the morality of critiquing science in the face of its obvious contributions to human flourishing was already a sticking point. Another first-time student in the class, who was concentrating in neuroscience, memorably summarized the argument from the technoscientific side: “well now you live longer so it’s like… ‘you’re welcome. Love, science.’” The comment produced laughter in the classroom, a delightfully blunt defense mounted in support of the enterprise and a way of dispatching interpretive handwringing and navel-gazing. Throughout my short career as an anthropologist of science I have often thought back to my classmate’s comment. Now, with that class closer in time to the original mapping of the human genome than to the present moment, I think back on her provocation with renewed appreciation. On the eve of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the postgenomic age, amid the gathering storm, I invite my fellow anthropologists of science to reflect: maybe it really is like that.

References

Bratton, Benjamin. 2021. “Agamben WTF, or How Philosophy Failed the Pandemic.” Verso. July 28, 2021. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/5125-agamben-wtf-or-how-philosophy-failed-the-pandemic.Freedman, David H. n.d. “A Prophet of Scientific Rigor—and a Covid Contrarian.” Wired. Accessed April 11, 2025. https://www.wired.com/story/prophet-of-scientific-rigor-and-a-covid-contrarian/.Fullwiley, Duana. 2008. “The Biologistical Construction of Race: ‘Admixture’ Technology and the New Genetic Medicine.” Social Studies of Science 38 (5): 695–735.Graeber, David. 2012. “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit.” The Baffler. March 12, 2012. https://thebaffler.com/salvos/of-flying-cars-and-the-declining-rate-of-profit.Gusterson, Hugh. 1997. “Studying Up Revisited.” Political and Legal Anthropology Review 20 (1): 114–19.Ioannidis, John P. A. 2005. “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.” PLOS Medicine 2 (8): e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124.Jirmanus, Lara Z., Rita M. Valenti, Eiryn A. Griest Schwartzman, Sophia A. Simon-Ortiz, Lauren I. Frey, Samuel R. Friedman, and Mindy T. Fullilove. 2024. “Too Many Deaths, Too Many Left Behind: A People’s External Review of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Pandemic Response.” AJPM Focus 3 (4): 100207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2024.100207.Kofman, Ava. 2018. “Bruno Latour, the Post-Truth Philosopher, Mounts a Defense of Science.” The New York Times, October 25, 2018, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/25/magazine/bruno-latour-post-truth-philosopher-science.html.Metzl, Jonathan M., and Anna Kirkland, eds. 2010. Against Health: How Health Became the New Morality. 1 edition. New York: NYU Press.Montoya, Michael. 2011. Making the Mexican Diabetic: Race, Science, and the Genetics of Inequality. University of California Press.Nader, Laura. 1972. “Up the Anthropologist: Perspectives Gained From Studying Up.” https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED065375.Offord, Catherine. 2025. “New Journal Co-Founded by NIH Nominee Raises Eyebrows, Misinformation Fears.” February 7, 2025. https://www.science.org/content/article/new-journal-co-founded-nih-nominee-raises-eyebrows-misinformation-fears.Pollock, Anne. 2012. Medicating Race: Heart Disease and Durable Preoccupations with Difference. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822395782.Roberts, Dorothy. 2012. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. New York; London: The New Press.Rommetveit, Kjetil. 2021. Post-Truth Imaginations: New Starting Points for Critique of Politics and Technoscience. Routledge.TallBear, Kim. 2013. “Genomic Articulations of Indigeneity.” Social Studies of Science 43 (4): 509–33.