In late 2022, I was enjoying my last semester in the United States, before I headed to Brazil to conduct ethnographic fieldwork. I spent the fall break in New York City and used my free time to head downtown and browse bookstores. I was specifically looking for books on psychoanalysis in perhaps the most (only?) Freudian city in the country. After all, NYC remains to this day a Freudian oasis within a USA that had largely moved past psychoanalysis and replaced it with cognitive-behavioral therapy, pharmacology, neuro-disciplines, and self-help.

Following the publication of the DSM-III (1980s) and the Decade of the Brain (1990s), American psychoanalysis was buried –according to many– ‘where it had always belonged, in the lumber-room of pre-scientific obscurantist quests for hidden meanings, alongside religious confessors and dream-readers’ (Zizek 2007:1). Humanities departments, once viewed as safe places for psychoanalysis after it was expelled from psychology schools, also began regarding it as a scientific imposture (kudos dear Sokal), a phallogocentric discourse (thank you cher Derrida) and a bad hermeneutic device (thanks Mr. Harold Bloom) that –adding salt to injury– was ultimately nothing more than a mere secularized extension of the Catholic confessionary (merci beaucoup Dr. Foucault).

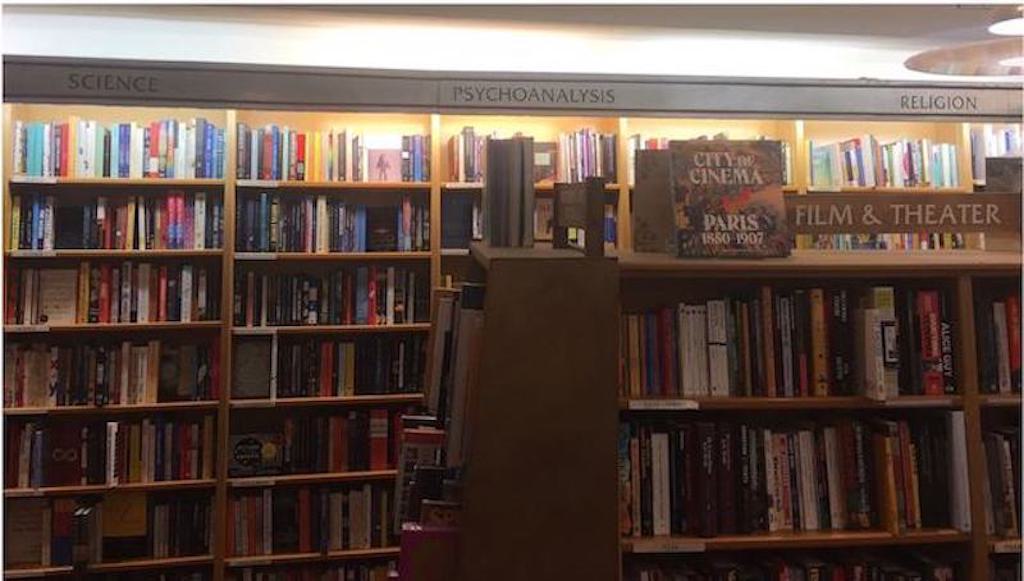

I entered a large independent bookstore after wandering the City for three hours. I was already exhausted from repeatedly asking for ‘books on psychoanalysis’ and clarifying ‘no, not psychology but psycho-anal-ysis’. A store clerk asked if he could help me, to which I only mumbled ‘Psychoanalysis…?’. He paused for a few seconds, ‘oh psychoanalysis, sure, between science and religion’. ‘That’s what I call good service’, I thought, ‘I came looking for books and got a demarcation!’. To my disappointment, the clerk’s response was more about physical location than about knowledge taxonomies, as the bookshelf for Psychoanalysis was indeed placed between the bookshelves of Science and Religion.

Life imitates art, but in NYC bookstores, shelves imitate demarcation (Image by author).

II

Psychoanalysis enjoys a different status in Latin America. It is not a marginal practice, despite the rising influence (and influx) of American psychology and psychiatry. Go to most Latin American major cities and you will find psychoanalysts at public hospitals, research groups, clinics, and universities. You will see them blended among humanists –literary scholars, linguists, philosophers, even mathematicians– but chances are, you may also find them teaching psychopathology, techniques on clinical interviewing, developmental psychology, or supervising clinical residencies.

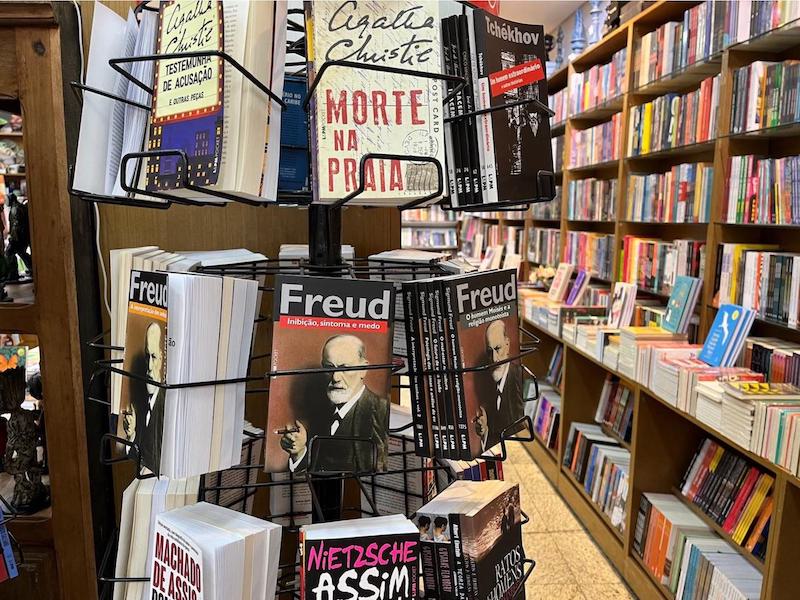

Newsstands sell paperback versions of Freud’s books, and high-profile publications have sections dedicated to psychoanalysis. In cities like Buenos Aires or Sao Paulo, psychoanalysts are regularly consulted, not only about subjectivity, mental health, or the love-life, but also about broader matters of public interest, ranging from the social impact of AI to cyber-bullying, from the war in Ukraine to climate change. They are regarded as experts on topics related to their craft, but also as intellectuals who ‘intervene in issues alien to their direct field of professional competence’ (Plotkin & Visacovsky 2008: 150).

Paperback section at a bus terminal bookstore in São Paulo (Image by author).

It is tempting to view Latin America as a psychoanalytic h(e)aven, but this picture is nuanced and ever-changing. Is Latin America just the last-man-standing of a dying paradigm, or is the region an alternative therapeutic and psy-landscape to the North-Atlantic one? The way we shape our response intertwines with our tacit geopolitics of knowledge. Is Latin America’s differential approach to psychoanalysis a historical anomaly in science’s natural progression? Is it a symptom of Latin American exotic exceptionalism? Can it be none of the above?

Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen, co-author of the Livre noir de la psychanalyse [1], clearly believes in the first option. For him, countries such as Brazil and Argentina today give the same credit to psychoanalysis as the United States in the ‘50s and ‘60s’. In 2005, Borch-Jacobsen predicted that ‘the disappearance of psychoanalysis is inevitable. Younger generations of specialists have other demands from a scientific point of view […] The days of Freud and his unearthly theories are numbered’ (Corradini 2005). 20 years later, neither Argentina nor Brazil have repeated the American path.

Borch-Jacobsen foresaw a decline caused by ‘the extraordinary advancement of neurosciences’ that demonstrate how, ‘in matters of the psyche, it is possible to achieve surprising short-term results with other therapies’ (Corradini 2005). While CBT and biopsychiatry have indeed gained greater public and institutional recognition, so have new-age therapies, self-help and Pentecostal religious healing. It would be more accurate to say that psychoanalysis is now sharing the podium. Unlike Borch-Jacobsen’s prophecy, the podium expanded on the side of science as much as it did on the side of religion, and even made room for magic and common sense (Csúri, Plotkin & Viotti 2022).

III

I landed in Brazil in 2023 to conduct an ethnography of the Psychoanalytic Clinic of the Genome, a unique space where psychoanalytic practitioners collaborate with genomic experts as part of a multidisciplinary approach to treat patients diagnosed with neuromuscular dystrophies [2]. This collaboration started after a contingent encounter in the early 2000s.

Almost at the same time when The Black Book of Psychoanalysis came out, a foundational moment was happening in Sao Paulo. A prestigious Brazilian cultural foundation had gathered prominent intellectual, scientific and cultural figures to discuss the challenges for Brazil in the 21st century. Dr. M, a renowned geneticist, and Dr. F, a prominent psychoanalyst, were seating next to each other at one of the roundtables.

The story, corroborated by both protagonists, goes as follows. Dr. M was mentioning the expected advances genetics would have in diagnosing and explaining diseases, which could lead to a new, predictive path for medicine. Dr. F, a physician himself, asked Dr. M if she believed in genetic determinism, ‘in the biunivocal relation between genotype and phenotype’, to which she responded ‘Absolutely no! Who told you such nonsense? There is no determinism between genotype the phenotype. Indeed, one of our big questions is to what extent are our genes affected by the experience of the environment’. The exchange continued. ‘In psychoanalysis, we don’t believe in determinism either’, said Dr. F, ‘between cause and effect, there’s always a split, a gap, and that’s where we intervene’. Then, Dr. M assented: ‘We are interested in how some people manage to protect themselves from the detrimental effects of a mutation. That’s where the environment can act and where psychoanalysis can play a role’.

Two decades after that mythical conversation, the Psychoanalytic Clinic of the Genome has co-treated almost 400 cases of Multiple Sclerosis, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, and many other conditions. It has endured political crises, a pandemic, a subsequent lockdown, the defunding of science during the Bolsonaro administration, and even low-key ‘science wars’. Lacanian psychoanalysts have participated in joint scientific studies, some of which even won important prizes at international medical and genetics conferences. Far from being a utopian assemblage doomed to a fleeting life, this collaboration became an enduring project reflective of Brazil’s post-neoliberal horizon of universal healthcare, state-funded science, and greater autonomy for Brazilian researchers when it comes to experimenting new scientific and therapeutic directions.

IV

A thick description of the conversation between Dr. M and Dr. F is a good starting point to understand science, genomics, health, and psychoanalysis at large in Brazil.

For starters, Dr. M and Dr. F, share a round table where none is given special authority. They speak as equals in a forum addressing public matters of national interest. Moreover, it is Dr. F, the psychoanalyst, who questions the geneticist, raising concern about (genetic) determinism. Conversely, it is the geneticist, Dr. M, who later agrees with the psychoanalytic stance by referring to ‘environmental factors’. Pushing further, their shared agreement on the existence of a gap within determinism foreshadowed the parameters of their son-to-come collaboration, based neither on their fusion nor the absorption of one by the other, but on maintaining their mutual dissonance.

Before psychoanalysts were invited to the project, the geneticists were working with cognitive-behavioral therapists, a more appropriate kind of partner glaring mutual epistemological and methodological affinities. However, this match, resting on epistemic consonance, did not bring results. One geneticist referred, ‘it didn’t work: patients were feeling much worse, and many interrupted their treatment’. This clearly contrasted with psychoanalysis: ‘I don’t even understand what the analysts do, but somehow it works, and you can see it on the patients’. Following Galison, treating neuromuscular dystrophies forces both disciplines to establish contact languages and systems of discourse that ‘hammer out a local coordination despite global differences’, even when they ‘disagree on the meaning of the exchange process itself’ (Galison 1997: 783).

V

How can we label this psychoanalytic incursion into genomic medicine? Is it even science?

Under Karl Popper’s stakes on scientific demarcation, psychoanalysis would not fulfill the minimum requirements of falsification of its own theory, hence it could not be a science. Up to this day, psychoanalysis is regarded, in many parts of the world, as a pseudo-science, a non-science, and even an anti-science; depending on who you ask.

At the Clinic, psychoanalysts are not attempting to recuperate their discipline’s lost scientific credibility by attaching themselves to a laboratory that carries ‘the official accolade of best science’ (Hacking 1988: 290). Neither are they seeking scientific validation, nor using a (more) legitimate form of scientific knowledge to confirm psychoanalytic theses; even less are they attempting to update their methods by borrowing from biomedicine. Rather, they view this as an opportunity to reinvent a psychoanalysis tied to the contemporary by breaking with what they see as widespread scholastic, exegetical, and ‘science-phobic’ psychoanalytic practices.

Instead of striving to reinscribe their discipline in the right side of the scientific demarcation, psychoanalysts are creating a tertiary terrain between the radical science/non-science separation. It is not about becoming a science or rebating the epithets of pseudo-science. Rather, “being with science”, “not being a non-science”, or “helping science” are the signifiers that circulate. This in-between space of indeterminacy has not prevented this hybrid assemblage from publishing peer-reviewed papers at top journals, winning scientific awards, getting grants, or structuring a multi-professional system of treatment and referral. In fact, their mutual epistemological dissonance (‘I don’t understand what they do …’) seems to be the condition of possibility for their pragmatic efficacy (‘… but somehow it works’).

Notes

[1] Edited by Catherine Meyer in 2005, The Black Book of Psychoanalysis: Living, Thinking and Being Better Without Freud (lit.) compiles more than 800 pages of archival and empirical studies aimed to demonstrate the fraudulent, unethical, and iatrogenic nature of psychoanalysis. The book immediately sold out in France and raised a series of controversies that even reached the higher spheres of French politics and legislation. Surprisingly, it was not translated into English perhaps, and among other reasons, because it was no longer necessary in Anglo-Saxon countries: by 2005, the Freud Wars were a thing of the past, especially in the US.

[2] Neuromuscular dystrophies are conditions that affect the nerve, muscle, or neuromuscular junction (where the nerve talks to the muscle) mostly by causing loss of strength, disability, and deformation. They primarily have a genetic basis, be it congenital or hereditary. Genetic testing is a crucial step for diagnosis, counseling and treatment.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Andra Sonia Petrutiu.

References

Corradini, L. (2005) ‘El psicoanálisis va a desaparecer’, dice Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen, La Nación (September 15). https://www.lanacion.com.ar/cultura/el-psicoanalisis-va-a-desaparecer-dice-mikkel-borch-jacobsen-nid738572/

Csúri, P.; M. Plotkin & N. Viotti (2022) Beyond Therapeutic Culture in Latin America: Hybrid Networks in Argentina and Brazil. Routledge.Galison, P. (1997) Image & Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics. The University of Chicago Press.Hacking, I. (1988) The Participant Irrealist at Large in the Laboratory, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 39(3): 277–294.Plotkin, M. & S. Visacovky (2008) Los psicoanalistas y la crisis, la crisis del psicoanálisis, Cahiers de LI.RI.CO 4: 149-163.Zizek, S. (2007) How to Read Lacan. W.W. Norton & Co.