In this text, we intend to revisit the well-known case of the Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Souza Santos, following its unfolding since the accusations that surfaced after the publication of this book “Sexual Misconduct in Academia” in 2023. We summarize the main events since then, focusing on developing a counter-manual that didactically organizes the regrettable way in which the intellectual responded to the accusations and systematically retaliated against the victims. We hope that this will contribute to ensuring that future reactions to such situations are guided by genuine desires for reparation and feminist transformation.

There is no birth in 1940 that excuses the situation Isabella describes; there is no cultural context that justifies a professional “deconstructor” of power relations claiming to have only now realized that he may have been “the protagonist of inappropriate behavior.” There is no mea culpa without admission of guilt. And there is certainly no self-criticism without criticism.

Câncio, Fernanda. Diário de Notícias 06/05/2023

Today’s text, inspired by organized anger, as Audre Lorde[1] says, is a kind of counter-manual for people who may eventually be accused of harassment, racism, or other forms of violence that, more recently, have been named, denounced, and constitute crimes under the law. Considering that these accusations have reverberated, to a greater or lesser extent, in institutional efforts to organize and respond to the accusations and complaints presented, we think that perhaps it is a contribution from the field of feminist anthropology to systematize examples of what NOT to do if this happens to you. We wrote this text out of absolute dissatisfaction with the fact that Boaventura de Souza Santos, a former professor at the University of Coimbra, accused of sexual harassment in 2023, returned to the headlines in 2025 after suing the women who denounced him for slander and defamation – a recurring behavior in cases involving harassment allegations[2] .

The image shows a university environment, with a poster prominently displayed that reads “I want to study without fear and harassment”. Photograph taken on the campus of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, by Fabiene Gama.

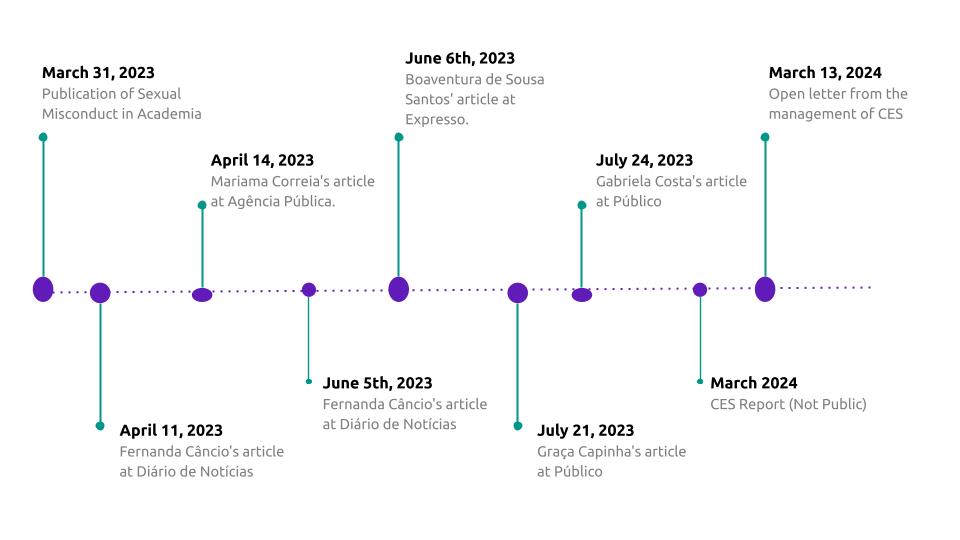

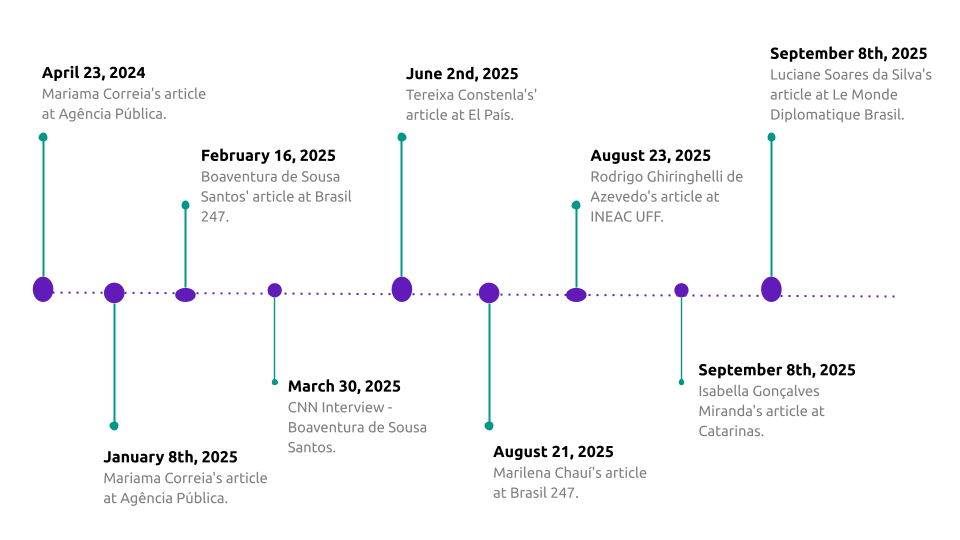

This text brings together some of what we have gathered about the chronology of this well-known case. For those who want to know more, the references we found are below. There are many, fortunately. In short, the case begins with the publication of an article in a collection by Routledge publishing house, entitled “Sexual Misconduct in Academia: Informing an Ethics of Care in the University“, organized by Erin Pritchard and Delyth Edwards. In it, three researchers wrote an article entitled “The walls spoke when no one else would: Autoethnographic notes on sexual-power gatekeeping within avant-garde academia”[3] , in which they did not explicitly name the intellectuals in question, but geopolitically situated these actors and their conduct. This quickly led to the Centre for Social Studies (CES) at the University of Coimbra and to researchers Boaventura de Souza Santos and other assistants and professors from the same research center.

The article narratively organized experiences that many of us women have already gone through in various situations and moments of life, especially in Latin American countries – and Brazil maintains an important colonial relationship with Portugal, which was at the center of this scandal. Practices and a daily work routine in which there is room for jokes, pranks, and friendships, and this informal atmosphere, so to speak, creates a kind of gray area where situations of abuse and sexual and moral harassment can occur. In this article, the authors recount a little about how this nebulous scheme between intimacy, friendship, and professional activities carried out outside the institutional context functioned.

The publication of this article triggered a series of other publications in newspapers, magazines, and news portals, which began to deconstruct (and humanize) the emblematic figure, supposedly above suspicion, of Boaventura de Souza Santos, a thinker who always defended “human rights, especially the rights of women, indigenous peoples, and the most disadvantaged minorities in the social, cultural, economic, or any other context” (Santos, 2023).

It was a kind of collective frustration and disappointment, perhaps equivalent to the also recent exposure of the harassment cases involving the jurist Sílvio Almeida in Brazil. These are male figures whom we, feminists who knew them “from afar,” considered potential political allies. But, through the courageous accusations made by women who decided to no longer remain silent, we learned that their daily practices did not correspond to the progressive ideas they defended in their writings. It is about this mismatch and incoherence between the intellectual work produced and the practical, everyday actions with the people we interact with at the university that we want to talk about.

To recover this long, well-documented history, we indicate the chronological sequence below. Much has been produced, and this is what we were able to gather; it is possible that other references exist as well. What we propose now is a practical, ironic, and angry exercise in presenting a counter-manual, that is, a manual of what NOT to do if you are ever accused of harassment.

The Counter-Manual for the Accused of Harassment

1. Don’t deny it

To deny it is cowardly, let’s face it. Several of Boaventura de Souza Santos’s reactions were more anchored in defending his own trajectory and greatness for the field of progressive left-wing thought than in recognizing that even a brilliant intellectual could be capable of being violent, aggressive, and acting in a way that makes women uncomfortable. So, if you are accused of harassment, stop and think if you didn’t actually act incorrectly. And own up to it. What may have been a joke to you, may have been embarrassment, inappropriate behavior, or violence to someone else.

2. Don’t justify it

Don’t say, “Oh, I’m sorry if you felt intimidated, that was normal in my time,” or “It’s a cultural thing, that’s always been normal for those born in 1940.” None of that justifies actions you may have taken in the past. It’s better to acknowledge the mistake, apologize, and actually make amends so that this type of situation is addressed. This is especially true if you are an intellectual who has included patriarchy and colonialism among the power structures you have analyzed. Recognizing that you are in a privileged position that can promote abuse of power should be at the heart of your conduct. This applies to white people and all other majority populations.

3. Do not condemn the women who denounced you

The retraction of the chapter, still inaccessible on the publisher’s website due to the legal process, establishes censorship over what was said. Not to mention the other developments, which can be seen in detail in the links below. Censorship only increases the likelihood that what is being said is true. If it were a lie, wouldn’t it be easier to refute? It’s important to remember that situations of sexual and moral harassment of this type are practically impossible to prove using the way evidence is currently required, unless the person is very suspicious and records their meetings without consent (something illegal according to our legislation and of an unlikely level of suspicion for ordinary people, although perhaps advisable for women in universities). It is very difficult to produce evidence against situations of harassment and misogyny. Often, these situations occur without witnesses and without the possibility of producing material evidence, which is the basis of the functioning of the legal system. In these situations, it is always the woman’s word that is confronted against the man’s. It is unacceptable that the words of 12 women (!!!!) are worth less than that of a single man, whoever he may be. The word of just one woman should be worth as much as that of a man, and even more so if the accusation in question is sexual harassment, considering the statistics, data, and knowledge we have about gender-based violence. It is unacceptable that, even in the case of a collective complaint, there are still people defending the character of the accused.

4. Don’t recruit colleagues to defend you, especially women

The testimony of other people not involved in the case in question, even if they are women, does not present elements that could refute what happened. A man can be kind to one woman and abusive to another. What will happen to the women who support you is that, in fact, they will lose their feminist political capital and their credibility along with you. For them, it’s like being dragged down by a drowning person.

5. Don’t sue the people who are accusing you

Respond to the accusations with honesty and a genuine commitment to change. This will likely yield far more public recognition than denying them to the end.

6. Don’t seek exposure

As tempting as it may be to defend your own honor, don’t seek out your journalist friends, whether in widely circulated newspapers, television, or the media in general. Of course, because of your prior legitimacy, you will succeed, as you will find a supportive colleague who will guarantee you that space. And this will be used to place your voice on a higher level of legitimacy and, therefore, make your narrative more valuable than that of women. The horrific interview that Boaventura gave to CNN Portugal and his article in the Expresso newspaper and on the 247 portal are revolting examples of how his legitimacy is used to reiterate violence, revictimize women, and give a platform to a person who should be duly judged and punished, in addition to his institutional removal. It is embarrassing to try to defend the indefensible.

7. Don’t resort to the old argument that it’s opposition mudslinging

This is the lamest excuse in history. Just because you’re seen as a great thinker from the Global South, originating from a relatively peripheral but European country like Portugal, doesn’t mean you’re incapable of making mistakes. What you do, even if it supposedly contributes to social thought, can also be condemnable. Even if your theoretical work benefits minority populations, everything falls apart when you don’t put what you write into practice, disrespecting students, researchers, and colleagues. As we’ve said, there isn’t necessarily a convergence between thought, publications, and daily practice, and the Boaventura case only demonstrates this. We hope that in the future researchers will be more consistent. We fight for that.

8. Don’t try to diminish or delegitimize the women who accused you

Remember that, in a patriarchal society, there is a social hierarchy between men and women. And that there are different social mechanisms that hinder the professional advancement of women in academia, which go far beyond their intellectual competence, with harassment being one of the main ones. Thus, if the women who accused you are not occupying the same hierarchical position as you, perhaps it is not due to incompetence, but to the impacts of the various forms of violence they have experienced, such as intellectual appropriation, harassment, and others. Above all, do not call women who have the courage to denounce the violence they have experienced “trauma sellers.”

9. Don’t confuse harassment with “pickup lines” or flirting

Don’t justify your behavior by saying that “any man my age who says he didn’t compliment or flirt with a woman in the 60s or 70s is either a liar or a hypocrite.” And don’t confuse harassment with flirting. In flirting, the desire for interaction is mutual. In harassment, it is not.

The 21st-century university needs to learn from the mistakes made by our institutional ancestors and respond quickly, recognizing its violent arm, its articulation with the State, with capitalism, with colonialism, with patriarchy. It needs to produce solutions and structures that allow these violences to be effectively repaired, avoided, and prevented, not just superficially. There is no longer room for the egoistic concentration of individual trajectories as if they were luminaries who are above good and evil and who should, therefore, be spared from their mistakes. This is not about punitivism or cancellation, but about making what we think, write, and defend coherent with what we do, how we live, the kind of world we produce within the university.

We believe in a feminist university where this type of violence does not go unnoticed. People – especially academics of our generation – need to learn to reposition the references we had with our professors and with the intellectuals who preceded us, who benefited from an absolutely hierarchical, elitist, and authoritarian operating system.

In this scheme, as you climbed the career ladder, you gained the benefit of not having to do a number of things yourself, having a number of people working and doing the boring parts of the job for you. We think we have to learn to earn the right to have more time for creative work, yes, without exploiting any type of worker or student who is at another stage of their career, and also without becoming intoxicated by the power that professional growth brings, by the mana that emanates from that other place.

We don’t have many good role models to inspire us. We are learning much more from our students and social movements about what we DON’T want and, step by step, building strategies so that institutions can strengthen us in an effective response to the kind of problem posed by an accusation like this of harassment, or gender violence of any kind. These are new times and, in fact, certain things are no longer acceptable. No matter how big the names are, they will forever remain in the 20th century.

* Support the defense of the victims in the Boaventura case. Link to the crowdfunding campaign here. Also check the Podcast: The Boaventura Case.

Timeline of Publications

Notes

[1] Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press, 1984.

[2] Almeida, Tânia Mara Campos de; Zanello, Valeska (org). Panoramas da violência contra mulheres nas universidades brasileiras e latino- americanas, Brasília: OAB Editora, 2022.

[3] Yes, the link does not open because the chapter page was taken down after a legal dispute.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Clarissa Reche.

References

Azevedo, R. G. (n.d.). Entre a obra e os fatos: os limites da defesa de Boaventura por Marilena Chauí. INEAC UFF. Available at: https://ineac.uff.br/entre-a-obra-e-os-fatos-os-limites-da-defesa-de-boaventura-por-marilena-chaui-rodrigo-ghiringhelli-de-azevedo/. Accessed on: Oct. 21, 2025.

Câncio, F. (2023, April 11). “Todas sabemos”. Boaventura Sousa Santos entre acusados de assédio no CES. Diário de Notícias. Available at: https://www.dn.pt/arquivo/diario-de-noticias/todas-sabemos-boaventura-sousa-santos-entre-os-acusados-de-assedio-no-cesuniversidade-de-coimbra–16160057.html. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Câncio, F. (2023, June 5). O “mea culpa” sem culpa de Boaventura. Diário de Notícias. Available at: https://www.dn.pt/arquivo/diario-de-noticias/o-mea-culpa-sem-culpa-de-boaventura-16483279.html. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.Capinha, G. (2023, July 21). Disse “científico”?!. Público. Available at: https://www.publico.pt/2023/07/21/opiniao/opiniao/cientifico-2057394. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Centre for Social Studies. (2024). CES Report (Not public).

Centre for Social Studies. (2024, March 13). Carta Aberta da Direção e da Presidência do Conselho Científico do CES. Available at: https://www.ces.uc.pt/pt/agenda-noticias/destaques/2024/carta-aberta-da-direcao-do-ces. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Chauí, M. (2025, August 21). Contra a calúnia. Em defesa de Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Brasil 247. Available at: https://www.brasil247.com/blog/contra-a-calunia. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

CNN Portugal (2025, March 30). CNN Entrevista – Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Available at: https://tviplayer.iol.pt/programa/cnn-entrevista/6787cc9ad34e94b82909b7bd/video/67e9c0060cf2ba9f720eb841. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Constenla, T. (2025, June 2). Dos años de parálisis judicial del ‘caso Boaventura’: el sociólogo que denunció el

patriarcado acusado de abusos por 13 mujeres. El País. Available in: https://cbf35f1c-4055-48a1-84e6-b7c08b9b7dbe.filesusr.com/ugd/7539b0_9a043c91c5204f7ba2350539a5b4f7ea.pdf?fbclid=PAQ0xDSwKrMoJleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABpyUUFnuYtoPBvb5SqByLbgwBRtQEuGKBceg6YzWDNXWdV_68iYsMJ9RcjA-E_aem_KJexi4h7viPEuFc5-2ZuxQ. Access em: 21 out. 2025.

Correia, M. (2023). Deputada brasileira denuncia assédio sexual de Boaventura durante doutorado. Agência Pública. Available at: https://apublica.org/2023/04/deputada-brasileira-denuncia-assedio-sexual-de-boaventura-durante-doutorado/. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Correia, M. (2024). Pesquisadoras deixam anonimato e contam que sofreram assédio de Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Agência Pública. Available at: https://apublica.org/2024/05/pesquisadoras-deixam-anonimato-e-contam-que-sofreram-assedio-de-boaventura-de-sousa-santos/. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Correia, M. (2025). Mulheres que denunciaram Boaventura de Sousa Santos por assédio são processadas na Justiça. Agência Pública. Available at: https://apublica.org/2025/01/mulheres-que-denunciaram-boaventura-de-souza-santos-por-assedio-sao-processadas-na-justica/. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Costa, G. (2023). Sobre feminismos e a academia. Público. Available at: https://www.publico.pt/2023/07/24/opiniao/opiniao/feminismos-academia-2057855. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Edwards, D., & Pritchard, E. (Eds.).(2023). Sexual Misconduct in Academia: Informing an Ethics of Care in the University. London: Routledge.

Miranda, I. G. (2025, September 8). Chaui, a verdade não se divide entre o ‘Santo Boaventura’ e as denunciantes. Catarinas. Available at: https://catarinas.info/chaui-a-verdade-nao-se-divide-entre-o-santo-boaventura-e-as-denunciantes/. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Santos, B. S. (2023, June 4). Uma reflexão autocrítica: um compromisso para o futuro. Expresso. Available at: https://expresso.pt/opiniao/2023-06-04-Uma-reflexao-autocritica-um-compromisso-para-o-futuro-581f0dd4. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Santos, B. S. (2025, February 16). História de uma difamação. Brasil 247. Available at: https://www.brasil247.com/blog/historia-de-uma-difamacao. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.

Silva., L. S. (n.d.). Por que é preciso defender Boaventura de Sousa Santos?. Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil. Available at: https://diplomatique.org.br/por-que-e-preciso-defender-boaventura-de-sousa-santos/. Accessed on: October 21, 2025.