Over the past decade, the concept of the gig economy has gained momentum in academic discourse. Often linked to temporary employment created by multinational technological corporations through digital platforms, the gig economy has transformed conventional discourses of labor and economy. It brought to the fore the increased precarity in employment, transformed modes of mobilization, fueled workers’ unionizing efforts, and produced new vocabularies (Vallas and Schor 2020; Khreiche 2018). In India’s dynamic economic landscape, these changes are particularly visible. One can argue that the use of digital technologies has reached a new peak in the ongoing global pandemic–as we have observed the changes in techno-bio-political regimes associated with COVID-19-tracking and increased reliance on mobile applications (Battin 2020; Segata 2020). In this light, focusing on India in the times of the COVID-19 pandemic becomes especially useful considering the narratives of hegemony and precarity often associated with gig labor within this geographical context, now exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Adams and Dickey 2000; Cruz-Del Rosario and Rigg 2019, 517-527). More specifically, in this post, I pay attention to India’s food delivery infrastructure (with the scene being dominated by two domestic companies, Swiggy and Zomato) and engagements with it on social media, as I reflect on them against the backdrop of the global pandemic in a densely populated and economically fraught country such as India.

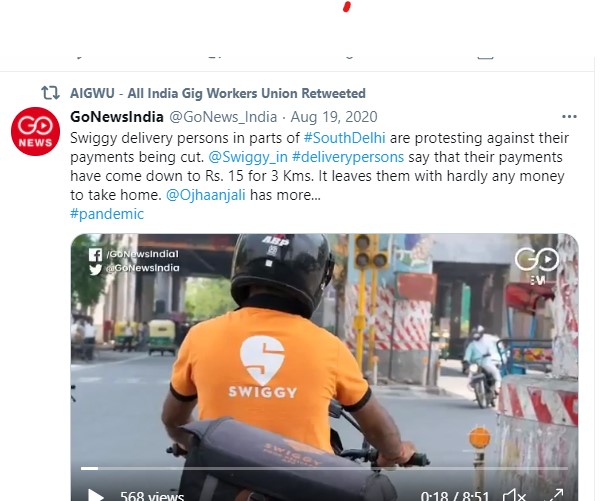

Screenshot from Twitter [1]

Redefining essential infrastructures digitally in a global pandemic

Joseph Masco defines crisis as a permanent narrative reinforced by news and mass media and argues that it is hard to reimagine a world without crisis (Masco 2018). Against this notion of crisis, considering the spread of COVID-19, the media narrative has constructed the pandemic as affecting all sections of the populations though with differences wrought by factors such as geography, class, access to mobility, etc. Thus, it is important to think about how political agency is constructed in this global pandemic and how existing infrastructures aid or hinder this process.

During the early days of the pandemic, the Indian state pursued the strategy of relying on science and technology, using the new social-distancing norms to govern the bodies of its citizens. At the same time, the state still gave way to the opportunities for big business: one illustrative example of which is the new government initiative to protect food delivery services. However, the Indian state’s governance of its citizens was also based on who it saw as legitimate citizens. This becomes evident when considering migrant laborers stranded in the early days of the nation-wide lockdown with nowhere to be in the large metropolitan cities that employed them and no way to get home when public transport shut down (Narayan 2020).

One approach to redefining essential infrastructures is to unpack the use of infrastructures during the pandemic and the framing of the term “essential” (Narayan 2020). Nikhil Anand argues that the legitimacy of the modern state and its technopolitical regime is ensured through infrastructures. The maintenance of these infrastructures as technologically advanced and “non-leaking” ensures their efficient mass use by its citizens (Anand 2019). Hence, adding the descriptor “essential” to infrastructures during the pandemic is a significant measure that takes place at the intersection of capital and state power that reimagines these laborers and infrastructures as essential (rather than precarious). Such a reframing leads one to wonder if this could be a “status accreditation” that constructs a narrative of praise and gratitude for these workers, while not supporting them through any other means. The idea of “status accreditation” is a play on the “status degradation ceremonies” that are observed in communication as tactics that work towards denouncing the status of specific people (Rouse 1996; Garfinkel 1956; Cavender et al. 2010). Thus, one can argue that resilience awards these abject bodies the nomenclature of essential workers. This, in turn, connects back to the Swiggy delivery workers’ strike in the Indian cities of Chennai, Hyderabad, and Noida in June 2020 (Swiggy is the largest food delivery platform in India, currently)–a strike organized in response to a lack of protective gear. At the time, the government did not step in; it was consumers who ended up sharing posts about this strike on social media instead. Hence, these laboring bodies, united by the disembodied platform that provided the gigs, were able to mobilize through social media, increasing visibility and opening up their actions to surveillance of the inter-consuming Indians.

Technologies of surveillance and techno-biopolitics

Neil Smith’s idea of legibility as the main concern of statecraft, shaped by a state mandate that followed a high modernist ideology drawing legitimacy from government power in the face of no resistance, is observable in countries like India, especially during the pandemic (Smith 2010; Scott 1998). By introducing mobile apps that help monitor the spread and presence of the coronavirus, the government identifies those citizens who have access to such mobile devices as worthy and attempts to govern their bodies through this techno-bio-politics. The government’s response to the lack of infrastructure at the moment when the migrant laborers were stranded at the beginning of the national lockdown across Indian metropolitan cities is key to understanding the state’s definition of legitimacy. It shows how the latter is rooted in documentation-based legibility, which was not available to most of these laborers (Narayan 2020).

Digital-space making and disembodiments

A sense of disembodiment experienced by both gig workers and consumers marks the operations of gig economies (Gray and Suri 2019). Gig workers are occupationally vulnerable due to the temporary nature of their jobs, workers’ sense of precarity, and platform-based vulnerabilities that speak to the disembodied space of work (Bajwa et al. 2018). The neoliberal context of gig economy also dictates the specific socio-political context in which workers take up these gigs. In a pandemic, such processes become further complicated. Workers’ sense of precarity is compounded by the need to produce, in order to survive on the platforms that employ them, since many platforms utilize rating systems that further alienate these workers from their workspace and products (Petroglieri et al 2018).

In a global pandemic that is remaking physical spaces by introducing social distancing measures, the move to online-education/workspaces serves to both bring together people and alienate them from their pre-existing offline networks. Through the complexity imposed by the digitalization of this delivery process, a sense of digital disembodiment is heightened by the alienation enforced by the pandemic – as seen through no-contact deliveries and curbside pickup, rather than in-person dining.

Questioning labor conditions through precarity and resilience

While the food delivery systems across the world have been affected, the Indian case is of particular interest because of the pervading precarity of labor and life for the employees. This precarity is, in turn, heightened by the construction of particular aesthetics of poverty and vulnerability by mediated narratives. It is only when these narratives are further amplified by the consumerist middle class through social media that the precarity of the workers gains legitimacy in the eyes of the state.

In October 2020, #babakadhaba was a trending hashtag on Indian news media and social media. The story of an old couple who owns a small roadside eatery that saw a huge drop in customers during the pandemic, in Western Delhi, captured the attention of the Indian public. Hailed as a story of the underdog and catapulted into national narratives through social media influencers and primetime news channels, the story of #babakadhaba signals hope and optimism in times of the global pandemic. As a result, customers now throng the dhaba; one of India’s biggest food delivery platforms, Zomato has listed them on their platform. Another offshoot of this incident has been the launching of a Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Urban and Housing Affairs with another important food delivery platform, Swiggy, to ensure a digital delivery platform for roadside food vendors across the country.

Caste and class dynamics have also played into the media narratives that are on display – while the consumers (of food and online media) are usually part of the middle class, the food delivery people are members of the working class, forced to become “essential workers” during the pandemic. The concept of caste, while not openly discussed in the news, is signaled through terms like hygiene and sanitation. On the one hand, these terms mask the narratives of contagion associated with caste pollution. On the other, they are currently being globally legitimized through pandemic practices. The caste narrative in the pandemic is also complicated by the fact that people belonging to “lower” castes are often poorer and hence forced into vulnerable positions that require them to take up these “essential” yet dangerous jobs. These workers lack access to protective gear while working jobs where employers advertised “complete adherence to WHO norms and safety precautions during COVID-19 pandemic” (Lalvani, Seetharaman 2020).

The flagrant disregard of the national government to the plight of millions of migrant workers stranded early on during the pandemic when metropolitan cities shut down, forcing them to walk thousands of kilometers to reach their home states, is further evidence of how laborers of the lower caste were the first target of a pandemic, not viewed as legitimate citizens worthy of state protection (Bansal 2021, Narayan 2020). Considered against the backdrop of a state that rushed to declare a national lockdown, creating categories of essential workers forged by poverty, enforced through police violence most often inflicted upon these very delivery workers, the narratives of precarity and resilience sewn into the fabric of the food delivery infrastructure are worth unpacking.

Class aesthetics and re-making social reproductions

Abjection as a visual aesthetic is the way this precarity is hailed and rewarded, as well as consumed, by the “legitimate” citizenry, where legitimacy is derived from class, caste, and documentation. This is observed in the reproduction and sharing of the information and social media posts that validate the struggles of certain gig workers which gain media traction – observed in the strike of the delivery people employed by one of India’s leading food delivery services as well as the case of the old couple in Delhi who owns a street-side eatery. However, these aesthetics of sharing can also be seen as reflective of the emancipatory power of hope, similar to those technocultural practices observed in the online engagements of Black Americans through political strategies and tactics for liberation, fueling social movements, observed during the widespread social media usage for mobilizing supporters during the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020 (Winstead 2019). The aesthetics of online sharing is observed through Twitter handles that seek to amplify the voices of the precarious that have emerged during the pandemic.

Conclusion

I write this post as a foray into unpacking these instances of precarity, camouflaged by narratives of resilience and re-made into hero-figures through the reification of essential infrastructures. With the increased emphasis on digital technologies during the pandemic, these technologies also act as tools for surveillance, furthering a techno-bio-political governance of legitimate citizens and promoting ideas of digital space-making amongst all sections of the society. Finally, utilizing labor as a disembodied process, gig economies ascribe to a certain aesthetics of social reproduction, based on pre-existing social networks. However, the onset of the pandemic has masked individual stories that speak of the struggles of social reproduction, in the form of narratives of resilience and hope undergirded by practices pertaining to health and anxiety, at a global scale.

Notes

[1] Transcription of image text: Retweeted by Twitter handle: AIGWU – All India Gig Workers Union. Original tweet by Twitter Handle GoNewsIndia @GoNewsIndia on Aug 19, 2020. Text in tweet “Swiggy delivery persons in parts of #SouthDelhi are protesting against their payments being cut. @Swiggy-in #deliverypersons say that their payments have come down to Rs. 15 for 3kms. It leaves them with hardly any money to take home. @Ojhaanjali has more… #pandemic ”

Bibliography

Adams, Kathleen M., and Sara Ann Dickey. 2000. Home and Hegemony: Domestic Service and Identity Politics in South and Southeast Asia. University of Michigan Press.

Anand, Nikhil. 2019. “Leaking Lines.” In Infrastructure, Environment and Life in the Anthropocene, edited by Hetherington Kregg, 149-160. Duke University Press.

Bajwa, Uttam, Denise Gastaldo, Erica Di Ruggiero, and Lilian Knorr. 2018. “The Health of Workers in the Global Gig Economy.” Globalization and Health 14 (1): 1-4.

Bansal, Parul. 2021. “Big and Small Stories from India in the COVID19 Plot: Directions for a ‘Post Coronial’ Psychology.” Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 55(1): 47-72.

Battin, Justin Michael. 2020. Instagram as a Catalyst for Digital Gemeinschaft during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam. Boasblog: Witnessing Corona, May 10, 2020. https://boasblogs.org/witnessingcorona/instagram-as-a-catalyst-for-digital-gemeinschaft-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-vietnam/.

Cavender, Gray, Kishonna Gray, and Kenneth W. Miller. 2010. “Enron’s Perp Walk: Status Degradation Ceremonies as Narrative.” Crime, Media, Culture 6 (3): 251-266.

Cruz-Del Rosario, Teresita and Jonathan Rigg. 2019. “Living in an Age of Precarity in 21st Century Asia.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (4): 517-527.

Garfinkel, Harold. 1956. “Conditions of Successful Degradation Ceremonies.” American Journal of Sociology 61 (5): 420-424.

Gray, Mary L. and Siddharth Suri. 2019. Ghost Work how to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Khreiche, Mario. 2018. “Milieus in the Gig Economy.” PhD dissertation, Virginia Tech.

Lalvani, Simiran and Bhavani Seetharaman. 2020. “The Personal and Social Risks that India’s Food Delivery Workers are Taking during COVID-19 .” The Wire, April 12, 2020. https://thewire.in/business/covid-19-food-delivery-workers.

Masco, Joseph. 2019. “The Crisis in Crisis.” In Infrastructure, Environment and Life in the Anthropocene, edited by Kregg Hetherington, 236-260. Durham: Duke University Press.

Narayan, Badri. 2020. “Has the Pandemic Changed how Caste Hierarchies Play Out in India?” The Wire, June 20, 2020. https://thewire.in/caste/covid-19-pandemic-caste-discrimination.

Petriglieri, Gianpiero, Susan Ashford, and Amy Wrzesniewski. 2018. “Thriving in the Gig Economy.” Harvard Business Review, March-April 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/03/thriving-in-the-gig-economy.

Rouse, Timothy P. 1996. “Conditions for a Successful Status Elevation Ceremony.” Deviant Behavior 17 (1): 21-42.

Segata, Jean. 2020. “Covid-19, Crystal Balls, and the Epidemic Imagination.” American Anthropologist, July 2, 2020. http://www.americananthropologist.org/2020/07/02/covid-19-crystal-balls-and-the-epidemic-imagination/.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press.

Smith, Neil. 2010. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. University of Georgia Press.

Vallas, Steven and Juliet B. Schor. 2020. “What do Platforms do? Understanding the Gig Economy.” Annual Review of Sociology 46: 273-294.