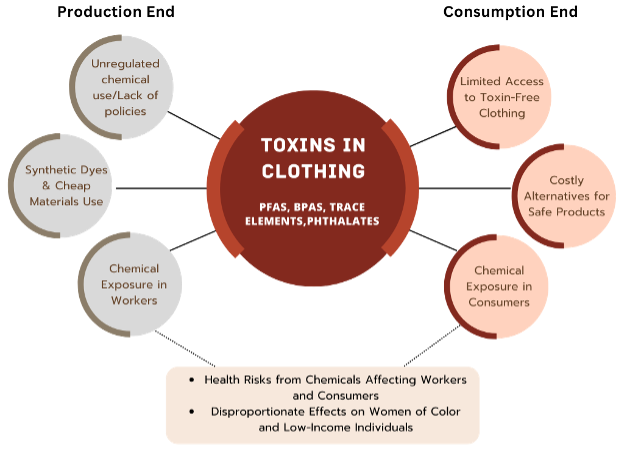

The interaction of toxins on the production end and consumer end of fashion consumption.

Have we ever considered how our clothes could impact our health? Could something as simple as underwear influence our fertility? Can our clothing choices be detrimental to our wellbeing?

These questions might be surprising, but recent studies have shown that the chemicals in our clothes can cause skin irritation, allergies, cancer, neurodevelopment disorders, reproductive toxicity, and much more (Cohen et al. 2023; Cowley et al. 2021; International Labor Organization 2021). And the fast fashion industry is at the center of this issue because of the cheap raw materials used in production (Pointing 2024). Fast fashion here mainly refers to a business model that focuses on quick and cheap production of trendy clothing (Sull and Turconi 2008).

The health concerns related to fast fashion primarily stem from chemicals in synthetic dyes and other low-quality raw materials used by manufacturers to keep the prices low. Exposure to these chemicals can be through the wastewater generated during manufacturing, and from direct contact with clothing itself.

Over the last decade, multiple studies and reports have documented how workers in the fashion industry faced health problems because of direct contact with chemicals in dyes (Mathews 2018; Rajan 2012; Regan 2020; Soyinka et al. 2024). However, we are now seeing that these chemicals are impacting the consumers who wear it as well (L. Nguyen 2022; Wolfe 2024). Wicker (2023) in her book highlights ethnographic accounts of people using mass-market brands and illustrates the struggles many face in their everyday lives due to the presence of chemicals in fabrics. Wicker (2023) described how Hiser, a nurse from Michigan, witnessed her child suffer from severe eczema flare-ups, due to the chemicals in the inexpensive polyester clothing he wore. Jaclyn, a former fashion production manager, developed rashes on her hands and arms after exposure to synthetic chemicals in clothing samples (ibid). The growing concern over chemicals in clothing is inevitable given the rising popularity of fast fashion in recent years and the reality that these chemically infused garments are in constant contact with the wearer’s skin.

Although the United States (US) and European Union (EU), the largest consumers of fast fashion, have policies that regulate the use of chemicals in consumer goods, the effectiveness of these regulations is often limited when it comes to the fast fashion industry (Durosko 2023). This is because the majority of these garments are produced outside their territories, in regions with less stringent laws, causing many production units to operate beyond the reach of strict regulatory oversight (ibid).

A Closer Look at the Impact of Chemicals

The chemical usage in our garments raises significant alarm, especially with harmful substances like Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)–popularly known as “forever chemicals”–along with bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and heavy metals found in garments from leading fast fashion brands (Carnevale 2023; Carrington 2023; Cobbing et al. 2024; Cowley et al. 2021; T. Nguyen and Saleh 2017). There is a mounting body of evidence linking exposure to forever chemicals, BPAs, and other substances with significant reproductive health impacts in women, including infertility, reduced fecundability, elevated pregnancy risks, and increased cancer risk (Cohen et al. 2023; Gillam 2023; NYU Langone Health 2020; Perkins 2024).

The situation is amplified by the fact that chemicals in textiles can penetrate the skin and enter the body (Iadaresta et al. 2018). Given that clothes are in constant contact with the body it is reasonable to conclude that clothing items significantly contribute to these health issues. Several studies have analyzed clothing samples from various brands, including fast fashion, and found high levels of PFAS and BPA in them (Cowley, Matteis, and Agro 2021; Difrisco 2022; Greenpeace International 2022; International Labor Organization 2021; Straková, Brosché, and Brabcová 2023). These findings underscore the widespread presence of chemical toxins in some of the most popular apparel brands with a devoted clientele like Shein, Patagonia, Under Armour, FILA, and more (Difrisco 2022; Greenpeace International 2022).

Studies have pointed out that PFAS, BPA, and phthalates are mainly endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can significantly impact the levels of reproductive hormones, leading to potential infertility and adverse pregnancy outcomes (Cohen et al. 2023; Durosko 2023; Karwacka et al. 2019; Qu et al. 2024). The endocrine system here refers to the network of glands and organs responsible for producing and regulating hormones, which also controls essential functions such as reproduction (National Cancer Institute 2011). In some cases, endocrine disruption due to PFAS exposure has also been linked to increased risk of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) related infertility (Wang et al. 2019).

The bad news is that many of these chemicals are found in all types of clothing items, including intimate apparel like underwear, which remains in constant contact with sensitive areas like the genitals, leading to prolonged periods of exposure and increasing the potential health risks. I shift the focus onto intimate wear in this post because it represents a fundamental clothing item that everyone should have access to without compromising their health. While much of the literature on chemical exposure addresses clothing in general, directing attention toward intimate wear can shed light on the unique risks posed by chemical exposure through such essential items.

A recent study examining around 120 women’s undergarments revealed high levels of heavy metals, including aluminum, zinc, and iron (T. Nguyen and Saleh 2017). Another study detected chemical additives containing heavy metals in women’s underwear and brassieres, which were found to carry carcinogenic risks (Chen et al. 2023). Reports have shown the presence of PFAS in menstrual underwear by Thinx, a popular female hygiene brand, highlighting its harmful impact on beneficial vaginal bacteria, increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases, and pregnancy complications (Choy 2020; Gupta 2023).

The presence of chemicals and heavy metals in intimate wear poses significant health risks. This issue also prompts consideration of the social dynamics that influence purchasing decisions for intimate wear and broader access to safe products and healthcare.

Social Dimensions of Health, Toxins, and Gender

A common factor among the brands where toxins were detected is that they are major fast fashion companies with significant market shares, often associated with widespread availability and affordability (Cowley et al. 2021; Difrisco 2022; Greenpeace International 2022). Returning to one of the most fundamental pieces of clothing, underwear from a fast fashion brand costs as low as $5, whereas underwear from brands that produce chemical-free alternatives typically range from $18 to $50 on average (Plell 2017; Tracy 2024). For an item as simple as underwear, spending up to ten times more on nontoxic underwear is simply not feasible for the average consumer. This also forces many to choose cheaper but potentially more harmful alternatives.

Fast fashion appeals to consumers across different socioeconomic levels, yet it is particularly attractive to those from lower income groups because of its affordability and availability (Ramirez 2023). This is particularly relevant to the discussion on intimate wear, because items like underwear cannot be thrifted due to hygiene concerns (Morais et al. 2020). Consequently, many consumers may choose intimate wear produced by fast fashion brands. Therefore, exposure to these chemicals poses a higher risk for people with lower socioeconomic status, who are more likely to rely solely on fast fashion.

Chemicals in clothing lead to poor health outcomes for women in general, but women of color may face even higher risk. In the US, women of color face compounded risks due to their lower income levels, which underscores the economic constrains influencing their purchasing decisions (Kochhar 2023; Social Security Administration 2023). These financial limitations might compel them to buy fast fashion clothing, particularly intimate wear. The risk is further exacerbated by inadequate healthcare access and insurance coverage, with approximately 9.5 million women aged 19-64 being uninsured in 2021 (KFF 2023). This situation highlights the intricate interplay between toxins, health disparities, and gender.

While consumers are at risk, it’s important to point out that garment workers in manufacturing countries, such as India, also face similar health concerns due to chemical exposure in dyes (Rajan 2012). Approximately 94 million people work in the garment industry worldwide, with women making up 60% of the workforce globally and nearly 80% in some regions (International Labor Organization 2023). This further reveals the skewed burden this industry places on women workers in the Global South.

The complex relationship between toxins, socioeconomic status, gender and race highlights three important points:

- The sociotechnical system of fashion operates on an ethos that puts the health and wellness of users at risk. Within this system, fast fashion brands prioritize profits over quality, making it difficult for the average consumer to access safe, toxin-free clothing.

- This case highlights how health risks through chemical exposure in clothes is a systemic issue. The lack of regulation, transparency, and accountability in the fashion industry continue to marginalize those already faced with precarious social and economic conditions.

- The toxins in our clothes produce asymmetrical effects, putting women of color and people from lower socioeconomic status at a higher risk. This also includes garment workers in the Global South.

Call for Action

Through this article, I not only draw attention to the hidden side of fashion toxins that are impacting the health of consumers and garment workers, but also the relationship with social facets of the modern world. Given the disproportionate impact of this industry on female consumers and garment workers, a call for action becomes crucial. The asymmetric effect on women reflects the heightened vulnerability to the industry’s use of harmful chemicals leading to health risks.

It is imperative to not only advocate for systemic changes in this industry, but also ensure that we pay attention to the fact that the health risks are not the same for everyone. Policymakers, industry leaders, and advocacy groups must address these challenges effectively. Additionally, as we are only beginning to grasp how chemicals in garments affect overall human well-being, our understanding of their full impact on health remains limited. Therefore, there is a pressing need for researchers and scientists to thoroughly examine and unpack these effects. Social scientists should also examine the nuances of chemical exposure in fashion, including its impact on directly affected groups, vulnerable populations, and the systemic barriers to shifting towards a more sustainable fashion system.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Ziya Kaya

References

Carnevale, Sophie. 2023. “What You Need to Know About BPA in Clothing.” Center for Environmental Health. https://ceh.org/what-you-need-to-know-about-bpa-in-clothing/.

Carrington, Damian. 2023. “‘Forever Chemicals’ Linked to Infertility in Women, Study Shows.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/apr/06/forever-chemicals-infertility-women-pfas-blood (October 18, 2024).

Chen, Hanzhi, Jiali Cheng, Yuan Li, Yonghong Li, Jiayu Wang, and Zhenwu Tang. 2023. “Occurrence and Potential Release of Heavy Metals in Female Underwear Manufactured in China: Implication for Women’s Health.” Chemosphere 342: 140165. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140165.

Choy, Jessian. 2020. “My Menstrual Underwear Has Toxic Chemicals in It | Sierra Club.” https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/ask-ms-green/my-menstrual-underwear-has-toxic-chemicals-it (August 22, 2024).

Cobbing, Madeleine, Viola Wohlgemuth, and Lisa Panhuber. 2024. Taking the Shine off SHEIN: A Business Model Based on Hazardous Chemicals and Environmental Destruction. Germany: Greenpeace Germany.

Cohen, Nathan J., Meizhen Yao, Vishal Midya, Sandra India-Aldana, Tomer Mouzica, Syam S. Andra, Srinivasan Narasimhan, et al. 2023. “Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Women’s Fertility Outcomes in a Singaporean Population-Based Preconception Cohort.” The Science of the total environment 873: 162267. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162267.

Cowley, Jenny, Stephanie Matteis, and Charlsie Agro. 2021. “Experts Warn of High Levels of Chemicals in Clothes by Some Fast-Fashion Retailers.” CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/marketplace-fast-fashion-chemicals-1.6193385 (October 29, 2024).

Difrisco, Emily. 2022. “New Testing Shows High Levels of BPA in Sports Bras and Athletic Shirts.” Center for Environmental Health. https://ceh.org/latest/press-releases/new-testing-shows-high-levels-of-bpa-in-sports-bras-and-athletic-shirts/ (October 30, 2024).

Durosko, Elizabeth. 2023. “Death by Fashion: Consumers Face Health Risks By Purchasing From Unregulated Fast Fashion Brands.” Loyola Consumer Law Review.

Gillam, Carey. 2023. “‘Forever Chemical’ Exposure Linked to Higher Cancer Odds in Women.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/sep/18/pfas-forever-chemicals-exposure-cancer-women (November 1, 2024).

Greenpeace International. 2022. “Taking the Shine off SHEIN: Hazardous Chemicals in SHEIN Products Break EU Regulations, New Report Finds.” Greenpeace International. https://www.greenpeace.org/international/press-release/56979/taking-the-shine-off-shein-hazardous-chemicals-in-shein-products-break-eu-regulations-new-report-finds/ (October 30, 2024).

Gupta, Alisha Haridasani. 2023. “What to Know About PFAS in Period Underwear.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/20/well/pfas-thinx-period-underwear.html (November 5, 2024).

Iadaresta, Francesco, Michele Dario Manniello, Conny Östman, Carlo Crescenzi, Jan Holmbäck, and Paola Russo. 2018. “Chemicals from Textiles to Skin: An in Vitro Permeation Study of Benzothiazole.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 25(25): 24629–38. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-2448-6.

International Labor Organization. 2021. Exposure to Hazardous Chemicals at Work and Resulting Health Impacts: A Global Review.

International Labor Organization. 2023. “How to Achieve Gender Equality in Global Garment Supply Chains.” https://webapps.ilo.org/infostories/en-GB/Stories/discrimination/garment-gender#introduction (November 10, 2024).

Karwacka, Anetta, Dorota Zamkowska, Michał Radwan, and Joanna Jurewicz. 2019. “Exposure to Modern, Widespread Environmental Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Their Effect on the Reproductive Potential of Women: An Overview of Current Epidemiological Evidence.” Human Fertility 22(1): 2–25. doi:10.1080/14647273.2017.1358828.

KFF. 2023. “Women’s Health Insurance Coverage.” KFF. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage/ (October 29, 2024).

Kochhar, Rakesh. 2023. “The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/03/01/the-enduring-grip-of-the-gender-pay-gap/ (November 9, 2024).

Mathews, Brett. 2018. “Chemical Exposure for Workers a ‘Global Health Crisis’ Says UN Briefing.” Apparel Insider. https://apparelinsider.com/chemical-exposure-for-workers-a-global-health-hazard-says-un-report/ (October 30, 2024).

Morais, Carla, Gianni Montagna, and Ana Sousa. 2020. “Underwear in Personal Wardrobe – A Study About Consumption and Disposal.” In Advances in Industrial Design, eds. Giuseppe Di Bucchianico, Cliff Sungsoo Shin, Scott Shim, Shuichi Fukuda, Gianni Montagna, and Cristina Carvalho. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 785–91. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-51194-4_102.

National Cancer Institute. 2011. “Definition of Endocrine System – NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms – NCI.” https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/endocrine-system (November 5, 2024).

Nguyen, Lei. 2022. “The Danger of Sweatshops.” Earth.Org. https://earth.org/sweatshops/ (October 31, 2024).

Nguyen, Thao, and Mahmoud A. Saleh. 2017. “Exposure of Women to Trace Elements through the Skin by Direct Contact with Underwear Clothing.” Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 52(1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/10934529.2016.1221212.

NYU Langone Health. 2020. “As Evidence of ‘Hormone Disruptor’ Chemical Threats Grows, Experts Call for Stricter Regulation.” NYU Langone News. https://nyulangone.org/news/evidence-hormone-disruptor-chemical-threats-grows-experts-call-stricter-regulation (November 1, 2024).

Perkins, Tom. 2024. “Women Exposed to ‘Forever Chemicals’ May Risk Shorter Breastfeeding Duration.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jun/26/women-breastfeeding-forever-chemicals (November 1, 2024).

Plell, Andrea Plell. 2017. “4 Truths Behind Fast Fashion Underwear — Remake.” https://remake.world/stories/style/4-truths-behind-fast-fashion-underwear/ (November 1, 2024).

Pointing, Charlotte. 2024. “Toxic Chemicals in Ultra Fast Fashion Could Be Harming Your Health.” Good On You. https://goodonyou.eco/chemicals-in-fast-fashion/ (October 4, 2024).

Qu, Rui, Jingxuan Wang, Xiaojie Li, Yan Zhang, Tailang Yin, and Pan Yang. 2024. “Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Affect Female Reproductive Health: Epidemiological Evidence and Underlying Mechanisms.” Toxics 12(9): 678. doi:10.3390/toxics12090678.

Rajan, M. c. 2012. “Water of Infertility: Polluted Noyyal River in Tamil Nadu Is Turning Land and People Barren.” Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/indiahome/indianews/article-2177320/Water-infertility-Polluted-Noyyal-river-Tamil-Nadu-turning-land-people-barren.html (October 18, 2024).

Ramirez, Izzie. 2023. “It’s Time to Break up with Fast Fashion.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/even-better/2023/11/14/23955673/fast-fashion-shein-hauls-environment-human-rights-violations (November 16, 2024).

Regan, Helen. 2020. “Asian Rivers Are Turning Black. And Our Colorful Closets Are to Blame.” CNN. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/dyeing-pollution-fashion-intl-hnk-dst-sept/index.html (April 25, 2023).

Social Security Administration. 2023. “Statistics at a Glance: Earnings of Women Aged 20–59, by Age Group and Race/Ethnicity.” https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/factsheets/at-a-glance/earnings-women-age-race-ethnicity.html (November 9, 2024).

Soyinka, Oluwatosin O., Akinwunmi F. Akinsanya, Festus A. Odeyemi, Adebayo A. Amballi, Kolawole S. Oritogun, and Omobola A. Ogundahunsi. 2024. “Effect of Occupational Exposure to Vat-Textile Dyes on Follicular and Luteal Hormones in Female Dye Workers in Abeokuta, Nigeria.” African Health Sciences 24(1): 135. doi:10.4314/ahs.v24i1.17.

Straková, Jitka, Sara Brosché, and Karolína Brabcová. 2023. Toxics in Our Clothing: Forever Chemicals in Jackets and Clothing from 13 Countries.

Sull, Donald, and Stefano Turconi. 2008. “Fast Fashion Lessons.” Business Strategy Review 19(2): 4–11. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8616.2008.00527.x.

Tracy, Teri. 2024. “Non-Toxic and Comfy Underwear for Sensitive Skin and Eczema.” Ecocult®. https://ecocult.com/eco-non-toxic-organic-comfortable-underwear/ (November 9, 2024).

Wang, Wei, Wei Zhou, Shaowei Wu, Fan Liang, Yan Li, Jun Zhang, Linlin Cui, Yan Feng, and Yan Wang. 2019. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances Exposure and Risk of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Related Infertility in Chinese Women.” Environmental Pollution 247: 824–31. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.039.

Wicker, Alden. 2023. To Dye For: How Toxic Fashion Is Making Us Sick–and How We Can Fight Back. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Wolfe, Isobella. 2024. “Textile Dyes Pollution: The Truth About Fashion’s Toxic Colours.” Good On You. https://goodonyou.eco/textile-dyes-pollution/ (October 18, 2024).