The atmosphere of anxiety concerning the Anthropocene amplifies when considering how its eerie and unwieldy forces affect our bodies. Across posthumanist, science studies, and new materialist discourse, the concern about corporeal impacts seems to huddle around a particular set of words: porous, permeable, vulnerable, sensitive. These are invoked as scholars seek to describe the status of bodies threatened by invisible, global, and pernicious toxins.

In a looping story of strata and sediment and edible rocks, this essay similarly seeks to articulate the material instabilities of bodies in an epoch that itself resists clear definition. Through the generative space of contradictions, it serves as a somewhat experimental back-and-forth between permeable anthropos bodies and the epoch defined by the materials transgressing those bodies; between tangible forms of evidence and ephemeral ones; between precision and porosity.

A Derelict Epoch

The term “Anthropocene” has become more of a socio-cultural (and I would argue even aesthetic) term in academic discourse, known best, perhaps, for its many critiques. Scholars have debated the origin of the Anthropocene, arguing that the term falsely attributes ecological harm to “all humans” (anthropos) as a homogenous species-wide entity,[1] drawing attention, instead, towards specific systems of harm.[2] These debates are not inconsequential: the lived reality of any such epoch is built not just from scientific data, but from the social construction of the epoch as well. However, as a student of New Materialism, I cannot ignore the material processes driving scientific nomenclature and their real-world impacts. Despite the significance of the Anthropocene’s critiques, its validation remains the authority of geologists; specifically, a sub-group of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (known as ICS; a governing scientific body of geologists) who has voted[3] on its nomenclature. Francine McCarthy, Professor of Earth Sciences at Brock University and a member of the ICS’s Anthropocene Working Group, explained the significance of the vote to officially ratify the term: “It matters if the world’s institutions formally recognize this era as a new earth systems reality,” she said. If countries and institutions were forced to recognize that the world has moved to a fundamentally different bio-geo-chemical reality, it would follow that they can’t necessarily regulate the environment like they used to, leading to potential changes in policy.

Deep Time’s Lithic Punctuation Marks

Geologists define planetary history in eons, with subdivisions in eras, periods, epochs, and ages. Any transition between these tracts of time (which each might span tens of millions of years) could be nothing but fuzzy and porous, as one species may linger longer, or certain climatic changes could occur quite gradually. Yet geologists must formalize the distinctions between segments of time with something exact, and in fact, a single thing—one impossibly useful fossil or rock or line in a cliff face somewhere on Earth that acts as a global reference point, known as a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (or GSSP). GSSPs mark the beginning of each new unit of geologic time. They tolerate a level of arbitrariness[4] in their exact location in order to prioritize a map of deep time without overlaps, gaps, or inconsistencies. For the geologists advocating for the Anthropocene’s ratification,[5] stratigraphic changes from the Holocene, thus, must be demonstrated through a single GSSP—in this case, a sediment core taken from Crawford Lake in Canada.

Photograph of a dried sediment core from Crawford Lake taken in January, 2024. Image by Author.

In 2024, I attended an interdisciplinary symposium[6] that included ICS members at Brock University, just 50 miles from where scientists dredged their proposed GSSP from the depths of Crawford Lake. This sediment core is considered the strongest evidence for a new epoch, encapsulating the Great Acceleration—a sharp uptick in a host of environmental changes that all coincided around 1950. These changes are, importantly, visible in the cores taken from the lake, in a near-ideal compilation of Anthropogenic “Greatest Hits:” a spike in plutonium from the first nuclear bomb tests, fly ash particles from fossil fuel combustion, increased atmospheric CO², heavy metal concentrations, microplastics, nitrogen, and biotic signals (such as changes to phytoplankton from acid raid, or changes in microscopic pollen phytoliths depicting declines in plant species due to human activity).[7]

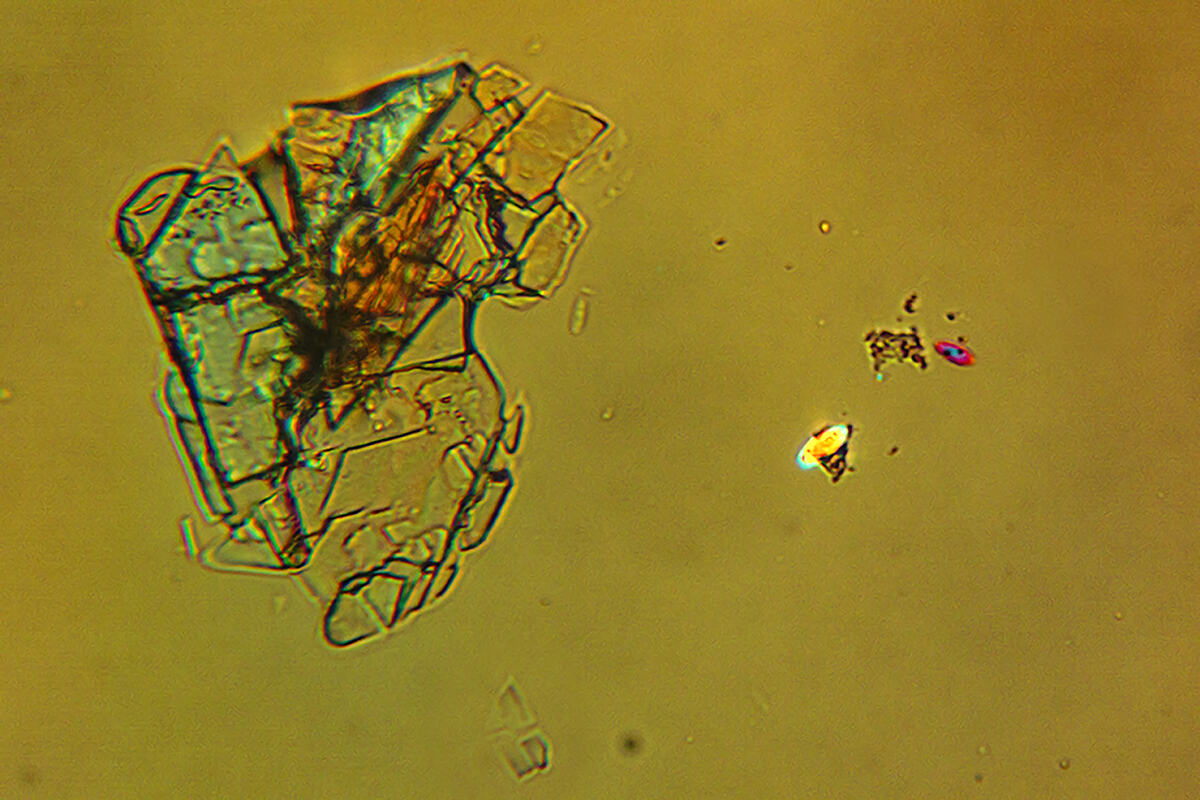

Microscopy image of a microplastic particle found in Troy, NY tap water in 2024. Image captured by Author in collaboration with Sarah Cadieux, Earth Science Professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, through a project supported by NATURE Lab and the Sanctuary for Independent Media.

Martin Head, the Chair of the ICS Sub-commission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, explained the Crawford Lake core as a “sensitive proxy” for the epoch. Perhaps because of my background in sensory experience and embodied art practice, I immediately pictured sensitive bodies—ones that could sense and feel the evidence of environmental changes. I realized that each of us, too, “sediment” Anthropogenic markers within our bodies, from elevated levels of lead to the pesticides, PFAS, and microplastics accumulating in our blood. If proxies are that which can take the place of something else,[8], in this case, then bodies are the place where materials are continually taking place(s) across entities, human and the more-than-human.

Our Bodies as Proxies for the Anthropocene

While certainly not reliable as a stratigraphic marker for the purposes of geologic science, bodies might make a more appropriate representation of the Anthropocene exactly for their lack of discrete boundaries—for their porosity and permeability to the same substances demarcated by the sediment core at Crawford Lake—which so characterizes eco-bio-chemical phenomena since the 1950s. We are similarly stratified by these material agents.

This idea has precedent in Feminist New Materialist Stacy Alaimo’s concept of transcorporeality, in which “the human is always inter-meshed with the more-than-human world.”[9] In her figuring, transcorporeality “insists that the human is always the very stuff of the messy, contingent, emergent mix of the material world.” This inseparability is evident as pollutants and waste, while they pose unforeseen and “messy” problems ecologically, sometimes also emerge in the very flesh and blood of human bodies, as is the case with DDT, PFAS, heavy metals, and microplastics. For whatever material transformations geologists seek to verify, our bodies are similarly transformed, bearing their own bio-geo-chemical evidence of the Anthropocene, accumulating the materials which are also accumulating in the earth’s rock record.

The tools of stratigraphic knowledge were developed for much greater spans of time than the proposed Anthropocene (beginning in 1950), and a host of personal and political ambiguities make it difficult to collapse bio-geo-chemical phenomena into one discrete truth at such a resolution.[10] Furthermore, the transcorporeal Anthropocene body might exist at odds with conventional earth science epistemologies, as it simultaneously confers material evidence with validity (bodies as sedimentations of anthropogenic materials) at the same time as it insists on a constant, fluid, shape-shifting unknown. As Alaimo outlines, transcorporeality “entails a rather disconcerting sense of being immersed within incalculable, interconnected material agencies that erode… even our most sophisticated modes of understanding.”[11] Both individuals and society strain to reckon this ambiguity, as it requires contending with the altered materiality of the body as well as with “the invisibly hazardous landscapes of risk society.”[12] This complicates what and how we “know” environmental truths. The body-as-proxy haunts our understanding of selfhood, as well as our understanding of geologic time and the types of positivism which scaffold it. Many Anthropocene phenomena restore a sense of ambiguity in earth science epistemology; they seem to ask us to tolerate paraconsistent logics, producing contradictory double truths: plastic is not edible / we are eating plastic.

These “disconcerting” or unnerving destabilizations of self-and-other are not actually novel; humans have long contended with the potential horrors and ambiguities of material permeability in the everyday practice of eating.[13] Food is an intimate and relational encounter with the environment, as it is the way that our bodies figure, transform, and re-make landscapes through our interior. The permeability of the body is most evident in consumption, digestion, and metabolism—processes that transform ecological materials into the self.

Left: Untitled (Kaolin Clay Mine), gliceé archival print, 24×16, 2024. The author bites off a piece of a kaolin clay rock in a clay mine in Southern Georgia—a type of chalky clay which is eaten in some places across the southern United States. Right: Edible kaolin clay purchased from an online retailer of edible earth. Image by Author.

Anthro-Terroir

One of the most contested substances in the realm of consumption is earth itself—clay, dirt, and chalk have been consumed by cultures on every continent, and the practice is thought to date to human’s prehistory.[14] It is, however, pathologized in the United States as a disorder called pica, and is heavily stigmatized along racial and class lines.[15] So at the same time that our bodies are becoming a kind of accelerated strata, scholars are also struggling to understand those who engage in the intentional consumption of layers of earth.[16] The clay, chalk, and rocks eaten by geophagists fall outside cultural codes for “food” (on the scale of the raw and the cooked,[17] they may not qualify as either), seeming to force an uncomfortable closeness with the environment.

The desire to consume dirt or clay rocks, while ancient, seems to hold a peculiar force in the Anthropocene, as is suggested by Iemanja Brown: “Eating dirt in the midst of climate change brings the state of things directly into the body. This may be the case with all that is ingested, but with dirt, the human is especially vulnerable because the body becomes, like dirt itself, a container for industrial byproduct.”[18] Brown figures the similarities between soil and bodies for the byproducts of the Anthropocene, and the body not just as a passive proxy, but as conductive matter,[19] through which unseen dangers of late industrialisms may flow, transgress, and engender transformations.

Various edible clay rocks, served to guests at the author’s exhibition Asphaltos—Metabolizing Time at EMPAC in Troy, NY in 2023. Image by Author.

The act of eating earth intervenes into scientific knowledge-making practices that otherwise lay claim to defining the Anthropocene. Stratigraphy defines an epoch through distant, extracted sediment cores, yet geophagy allows direct, embodied contact with layers of sediment itself, which are accumulating the detritus of humankind—a kind of strange anthros terroir. Though undervalued in scientific discourse, the chemical senses (taste and smell) can produce environmental knowledge in relation to earth matter. Studies have shown that soil odor was a reliable method to assess soil fertility and toxicity,[20] individuals’ detection of odor in tap water was proven more sensitive for identifying toxins than scientific instrumentation,[21] and some geologists use taste to identify rocks.[22]

While research on the potential medical benefits of geophagy is plagued by inconsistency, one of the more generally accepted medicinal uses of edible clay is, in fact, as a way to reduce the porosity to toxins of one’s body. Bentonite clay enhances intestinal mucosal integrity, as it fortifies an important physical and chemical shield protecting the rest of the body from absorption of high levels of potential toxins or harmful substances.[23] Edible clay is often suggested in alternative health spaces (with varying degrees of credibility) as a “detoxifying” remedy for microplastics, pesticides, metals, or other anthropogenic materials in the body.

Detoxification is often framed as an escape from the perils of the Anthropocene, skirting the deep inequalities that truly define the problem.[24] And while detox protocols can encompass worthy holistic health practices, absolute detoxification as a goal is shot through with purity politics—a false hope for pure bodies that obfuscates inequality at its best, and perpetuates xenophobia at its worst. As if to demonstrate that detoxification is a false promise in the Anthropocene, many individuals have, instead, exposed themselves to harm through geophagy practices.[25] In a curious twist of fate, one might find herself nervously consuming the same earth we have irrevocably changed, seeking futilely to prevent anthropogenic toxicity from taking hold of her interior landscape, too.[26]

This paradox represents the desire for purity in a world where we must accept already-altered life[27] where the materials we put into the earth may also be digested back into our own bodies. Heightened anxieties around purity may in fact be symptoms of the unique ontological challenges of the Anthropocene. I will leave this story with all its loops and contradictions, resisting a satisfying conclusion which might cheapen the complexities at play. Instead, I offer encouragement to notice the paraconsistent and embodied porosities of the Anthropocene. Noticing practices, such as those offered by Anna Tsing,[28] are a way to cultivate intimacy with the environment; perhaps they could provide intimacy with the changes, vulnerabilities, and porosities of our bodies, too, generating a commitment to sit-with the unnerving ambiguities that arise. At the site of consumption and digestion, for example, we might stop to consider forms of repair or harm our food is endorsing, or what physical transformations result from a choice in eating, to a distant landscape or to the bacteria in our gut. What negotiation of risk and repair are being made? Our bodies, like sediment cores, may archive the Anthropocene, offering a visceral, everyday means of understanding this epoch through the act of eating.[1]

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Misria Shaik Ali.

Notes

[1] Heather Davis and Zoe Todd, “On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene,” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 16, no. 4 (2017).

[2] Two compelling arguments re-attribute and specify the Anthropocene’s causes to capitalism (“Capitalocene”) or to plantation agriculture (“Plantationocene”), since these systems are characterized by the extractive devaluation of life, both human and non. See: Andreas Malm and Alf Hornborg, “The geology of mankind? A critique of the Anthropocene narrative,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 1 (2014); Janae Davis, et al., “Anthropocene, Capitalocene,… Plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises,” Geography Compass 13, no. 5 (2019).

[3] The International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), of which ICS is a part, officially voted down the Anthropocene proposal in 2024, although the voting process was contested, with claims that conservatives and “ecomodernists” forced the “no” vote prematurely. See: Alexandra Witze, “Geologists reject the Anthropocene as Earth’s new epoch – after 15 years of debate.,” Nature (London) 627, no. 8003 (2024); Ian Angus, “Anti-Anthropocene Vote is ‘Null and Void’,” Monthly Review Online, 8 Mar 2024. https://mronline.org/2024/03/08/anti-anthropocene-vote-is-null-and-void/.

[4] Stephen L. Walsh, Felix M. Gradstein and Jim G. Ogg, “History, Philosophy, and Application of the Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP),” Lethaia 37, no. 2 (2004).

[5] Martin J. Head, et al., “The Anthropocene as an Epoch is Distinct From All Other Concepts Known By This Term: A Reply to Swindles et al. (2023),” Journal of Quaternary Science 38, no. 4 (2023).

[6] Two members of this group were also members of The Anthropocene Working group, a former working group of Sub-commission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS), itself a sub-group of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS).

[7] Colin Waters, et al., “Part 2: Descriptions of the Proposed Crawford Lake GSSP and Supporting SABSs. The Anthropocene Epoch and Crawfordian Age: Proposals By the Anthropocene Working Group,” (unpublished preprint, submitted to the ICS Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, 2024),

[8] Harper Douglas, “Etymology of proxy,” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed 11 March 2025, https://www.etymonline.com/word/proxy.

[9] Stacy Alaimo, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Indiana University Press, 2010), 2.

[10] Of course, this in turn also reveals how knowledge is socially constructed, as well as reveal the agencies of the non-scientists involved: hundreds of years of indigenous land relations, lake sediment flows, global political ideologies around climate change, bacterial histories, and chemical processes.

[11] Ibid., 17.

[12] Ibid.

[13] For more on the complications of subjectivity in eating, see: Annemarie Mol, Eating in Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

[14] Sera L. Young, Craving Earth: Understanding Pica: The Urge to Eat Clay, Starch, Ice, and Chalk (Columbia University Press, 2012).

[15] Ibid.

[16] As is pointed out by multiple scholarly reviews on the available research on geophagy, there is a lack of reporting on the practice, and geophagy has received limited and sporadic attention in medical or sociological literature. See: Peter W. Abrahams, “Geophagy and the Involuntary Ingestion of Soil,” in Essentials of Medical Geology (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2013).

[17] See: Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked (Harper & Row, 1969).

[18] Iemanjá Brown, “Dirt Eating in the Disaster,” in Timescales: Thinking Across Ecological Temporalities, ed. Bethany Wiggin, Carolyn Fornoff, and Patricia Eunji Kim. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 171.

[19] Ibid.

[20] S López-Aguilar, et al., “Soil Odor as An Extra-Official Criterion for Qualifying Remediation Projects of Crude Oil-Contaminated Soil.,” Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, no. 9 (2020).

[21] Christy Spackman, “In Smell’s Shadow: Materials and politics at the edge of perception,” Social Studies of Science 50, no. 3 (2020).

[22] Jan Zalasiewicz, “Eating Fossils,” Paleontological Association Newsletter (2017).

[23] Young, Craving Earth.

[24] See: Julie Guthman, The Problem With Solutions: Why Silicon Valley Can’t Hack the Future of Food (Berkley: University of California Press, 2024).

[25] JN Bonglaisin, et al., “Geophagia: Benefits and potential toxicity to humans—A review,” Front Public Health 10 (2022).

[26] I mean not to endorse any one reason for geophagy as more valid than another, and certainly not as a solution to the vulnerabilities of exposure in the Anthropocene. For more on the problem with “solutions,” see: Guthman, The Problem With Solutions: Why Silicon Valley Can’t Hack the Future of Food.

[27] See: Michelle Murphy, “What Can’t a Body Do?,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3, no. 1 (2017).

[28] Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, “Arts of Noticing,” in The Mushroom At the End of the World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

References

Abrahams, Peter W. “Geophagy and the Involuntary Ingestion of Soil.” In Essentials of Medical Geology, 433–54. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2013.

Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Angus, Ian. “Anti-Anthropocene Vote is ‘Null and Void’.” Monthly Review Online, 8 Mar 2024. https://mronline.org/2024/03/08/anti-anthropocene-vote-is-null-and-void/.

Bonglaisin, JN, NB Kunsoan, P Bonny, C Matchawe, BN Tata, G Nkeunen and CM Mbofung. “Geophagia: Benefits and potential toxicity to human—A review.” Front Public Health 10 (2022): 893831.

Brown, Iemanjá. “Dirt Eating in the Disaster.” In Timescales: Thinking Across Ecological Temporalities, edited by Bethany Wiggin, Carolyn Fornoff and Patricia Eunji Kim. 169–81. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Davis, Heather and Zoe Todd. “On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 16, no. 4 (2017): 761–80.

Davis, Janae, Alex A Moulton, Levi Van Sant and Brian Williams. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene,… Plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises.” Geography Compass 13, no. 5 (2019): 1–15.

Guthman, Julie. The Problem With Solutions: Why Silicon Valley Can’t Hack the Future of Food. Berkley: University of California Press, 2024.

Head, Martin J., Colin N. Waters, Jan A. Zalasiewicz, Anthony D. Barnosky, Simon D. Turner, Alejandro Cearreta, Reinhold Leinfelder, Francine M.G. McCarthy, Daniel de B. Richter, Neil L. Rose, Yoshiki Saito, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Yongming Han, Colin P. SumMerhayes, Mark Williams and Jens Zinke. “The Anthropocene as an Epoch is Distinct From All Other Concepts Known By This Term: A Reply to Swindles et al. (2023).” Journal of Quaternary Science 38, no. 4 (2023): 455–58.

López-Aguilar, S, RH Adams, VI Domínguez-Rodríguez, JA Gaspar-Génico, J Zavala-Cruz and E Hernández-Natarén. “Soil Odor as An Extra-Official Criterion for Qualifying Remediation Projects of Crude Oil-Contaminated Soil.” Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, no. 9 (2020 May 05): 3213.

Malm, Andreas and Alf Hornborg. “The geology of mankind? A critique of the Anthropocene narrative.” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 1 (2014): 62–69.

Mol, Annemarie. Eating in Theory. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Murphy, Michelle. “What Can’t a Body Do?” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3, no. 1 (2017): 1–15.

Spackman, Christy. “In Smell’s Shadow: Materials and politics at the edge of perception.” Social Studies of Science 50, no. 3 (2020): 418–39.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. “Arts of Noticing.” In The Mushroom At the End of the World, 17–25. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Walsh, Stephen L., Felix M. Gradstein and Jim G. Ogg. “History, Philosophy, and Application of the Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP).” Lethaia 37, no. 2 (2004): 201–18.

Waters, Colin, Simon Turner, Zhisheng An, Anthony Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Andrew Cundy, Ian Fairchild, Barbara Fiałkiewicz-Kozieł, Agnieszka Gałuszka, Jacques Grinevald, Irka Hajdas, Yongming Han, Martin Head, Juliana Ivar do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, Francine McCarthy, John McNeill, Eric Odada, Naomi Oreskes, Clément Poirier, Daniel Richter, Neil Rose, Yoshiki Saito, William Shotyk, Colin Summerhayes, Jaia Syvitski, Davor Vidas, Michael Wagreich, Mark Williams, Scott Wing, Jan Zalasiewicz and Jens Zinke. “Part 2: Descriptions of the Proposed Crawford Lake GSSP{ and Supporting SABSs. The Anthropocene Epoch and Crawfordian Age: Proposals By the Anthropocene Working Group.” Unpublished preprint, last modified submitted to the ICS Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, 2024.

Witze, Alexandra. “Geologists reject the Anthropocene as Earth’s new epoch – after 15 years of debate.” Nature (London) 627, no. 8003 (2024): 249–50.

Young, Sera L. Craving Earth: Understanding Pica: The Urge to Eat Clay, Starch, Ice, and Chalk. New York City: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Zalasiewicz, Jan. “Eating Fossils.” Paleontological Association Newsletter (2017): 31–35.