In a 1992 New York Times op-ed, Paul Lewis denounced the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) decision to exempt genetically engineered crops from case-by-case review. He likened modern agricultural scientists to the scientist Victor Frankenstein in Mary Shelley’s novel and introduced the now famous term “Frankenfoods.” Frankenfoods invokes Shelley’s Frankenstein to capture public unease about the unforeseen consequences of consuming genetically modified foods. The term soon drew scrutiny from proponents of the technology, including industry-sponsored front groups, agricultural businesses (also referred to as agribusiness), respected journalists, plant geneticists, and scientific organizations. Citing evidence of the proven safety of consuming genetically modified foods, they rejected the label as a reactionary, scientifically inaccurate, and fear-mongering indictment of a new and thus, unfamiliar, technology.

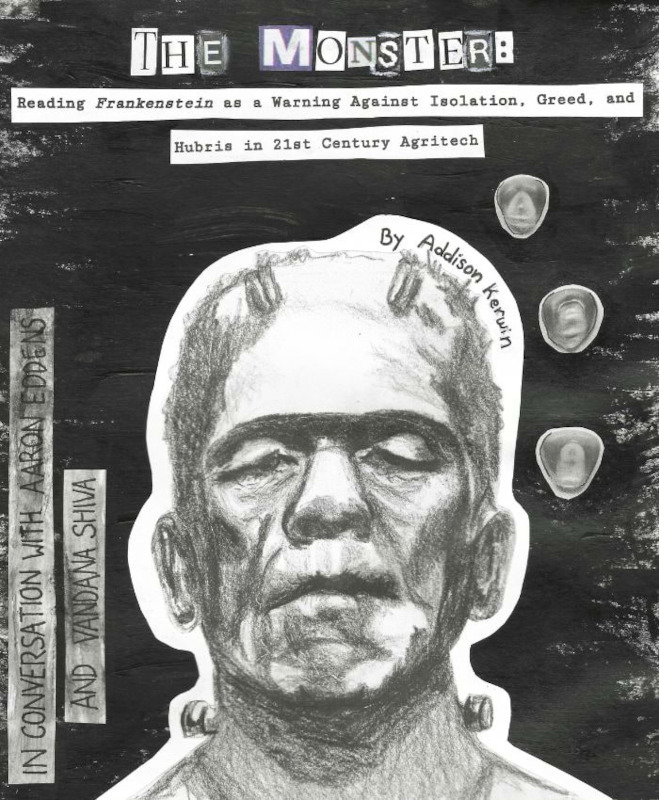

Cover page of the zine version of this essay, created for the Society for Social Studies of Science conference in Seattle. Collage and illustration of Frankenstein by author.

Reading GMOs in the true spirit of Shelley’s novel, however, encourages a specific attunement—one that both proponents and critics of the technology often overlook in their debates. Frankenstein isn’t a simple condemnation of technology. It is an interrogation of the sociocultural context in which inventions are conceived and deployed. The application of the “franken” prefix, then, should not be used—or read—simply as an expression of fear towards unnatural creations. Instead, it calls for an examination of how innovation, power, and avarice shape the development and impacts of genetic modification in the food system.

This understanding of Shelley’s novel is essential for clarifying the judgment embedded in the label “franken-foods.” If the novel works to direct attention towards the inventor, and even garner sympathy for the invention, then a Frankensteinian assessment of this technology will inherently start with its creators and their methodologies. It follows that an examination of genetic modification must center agribusiness. But how can we recognize a negligent scientist? What driving forces motivate agribusinesses to engineer this technology? What kinds of laboratory work—within the field of agricultural technologies—should prompt scrutiny? The novel helps us answer these questions.

Deconstructing ‘Franken’: Tracing Responsibility from Victor to Agritech

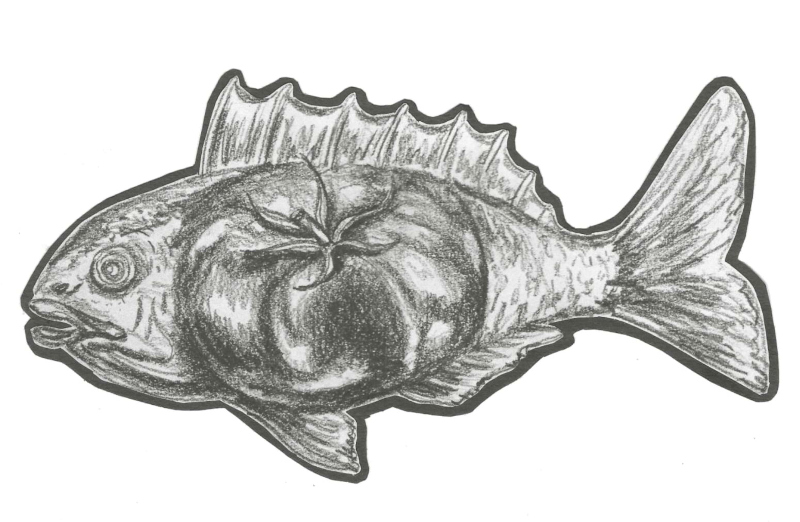

Rendering of a tomato-fish emblem, originally created and used by anti-GMO protestors in response to a DNA Plant Technology experiment. Scientists inserted a winter flounder gene into a tomato genome to test frost tolerance, but the resulting seed was never sold or distributed beyond the lab. Illustration by the author.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (or The Modern Prometheus) follows the story of a young inventor, Victor Frankenstein, who animates a monster using lightning and assembled parts from the bodies of human corpses. After the creature leaves the lab, it wreaks havoc on Frankenstein’s friends and family, disaster and death following in its wake. Public misconception has blurred the novel’s critique by erroneously identifying the monster as the titular character, “Frankenstein.” This cultural renaming shifts attention away from the human actor. However, a correct reading of Shelley’s title frames the scientist as the story’s central figure and bearer of responsibility.[1]

It is clear why readers misallocate blame since the monster’s animacy complicates the notion of responsibility. Through the novel’s sustained efforts to humanize the creature, however, Shelley shifts accountability back to Victor. In a passage, the monster illustrates his care for the humans he coexists alongside, stating “I had been accustomed, during the night, to steal a part of their store for my own consumption; but when I found that in doing this I inflicted pain on the cottagers, I abstained, and satisfied myself with berries, nuts, and roots which I gathered from a neighbouring wood” (Shelley 2012 [1818], 114). Far from an inherently wicked beast, the creature emerges as a thoughtful, articulate, and sympathetic narrator. The redemption of the monster’s inherent disposition underscores Shelley’s true critique of the inventor’s responsibility for the violence that ensues.

An analysis of Shelley’s allocation of blame reframes what “franken” signals in the term “franken-food.” Rather than marking genetically modified crops as inherently monstrous, the modifier highlights the responsibility of agritech creators, the ‘Frankensteins’ who engineer and deploy the technology.

Engineering for Glory and Capital: Parallels Between Victor Frankenstein and Agribusiness

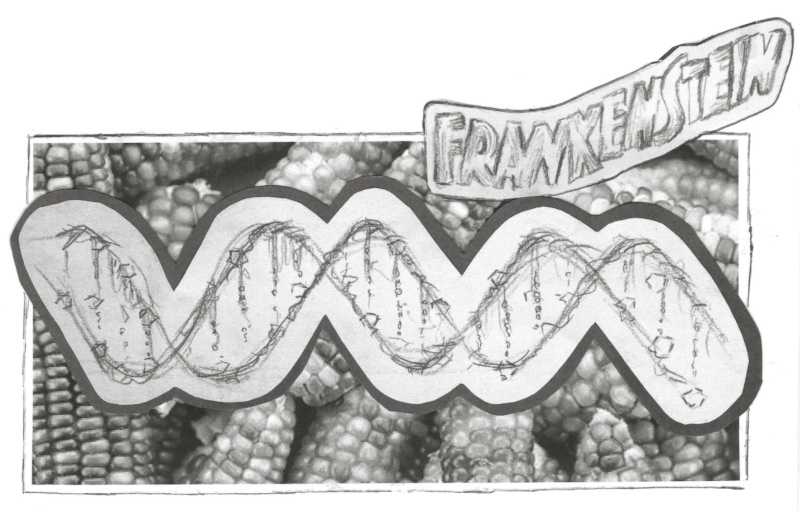

DNA rendering and title from the1931 Frankenstein film poster, layered over hybridized corn image. Collage and illustration by author.

In the novel, Shelley makes a clear case that the catastrophic outcomes of Frankenstein’s experiments are rooted in the inventor’s blind ambition and god complex. In the novel, Victor, the scientist, states, “what had been the study and desire of the wisest men since the creation of the world was now within my grasp” and reflects, with excitement, that a new species will worship him, owing their existence to their blessed creator (Shelley 2012 [1818], 53-55). He envisions his work as a way to immortalize his name and even create a subservient race rather than using his work to create a technology that will benefit humanity.

Shelley’s examination of the circumstances that shape and motivate Frankenstein’s scientific practice challenges the widely held assumption that technological innovation is a value-neutral process. Applying critical attention to agricultural invention illustrates that the motives of agribusiness—not the technologies themselves—determine the real world impacts of genetically modified organisms.

Driven by logics of capital accumulation, agricultural corporations may be said to share Frankenstein’s perilous arrogance and greed. Like Frankenstein, they have engineered new life forms—but their ambition extends even further, as commoditization drives them to exploit technology to reshape global systems. In Seeding Empire: American Philanthrocapital and the Roots of the Green Revolution in Africa, Aaron Eddens shows how major American corporations such as Monsanto and Dupont (now Corteva Agriscience) have pursued what they call a new Green Revolution in Africa, promoting their westernized technologies, such as genetically modified seeds, as universally superior. This project reflects the hubristic belief that these companies possess the authority and expertise to engineer an “optimal” model of farming—one that privileges Western ideals over local knowledge and autonomy. The growth of industry across the Atlantic does not merely mark an expansion of agricultural technology. It is also an epistemological conquest grounded in western ideas about how farming should be conducted. The introduction of GMO seeds to international markets is predicated on agricultural corporations pressuring governments to enforce seed patents and protect intellectual property. In African countries, however, seeds are generally considered a common heritage and a cultural resource. As Eddens (2024, 82) explains, the creation of agritech markets requires a rejection of this fundamental belief.

Furthermore—like Victor Frankenstein—agricultural corporations do not innovate purely for humanity’s benefit. Whereas Victor sought “dreams of virtue, of fame” (Shelley 254), corporations’ stated virtuous aim veils a profit motive, often at odds with their professed mission to build a just and sustainable global food system. Eddens (2024, 50) claims that these projects, while marketed as ways to help support parts of the Global South, identify Africa as an untapped frontier for the extraction of new profits. These businesses, which work with nonprofits, like the Gates Foundation, and government groups, emphasize that there is a ripe opportunity to use philanthropy “to open up new sites through which to generate profits for corporations” (Eddens 2024, 13). As corporations focus on expanding their wealth, real human lives are put to risk.

Constructing The Laboratory as a Site of Isolation, Exploitation, and Control

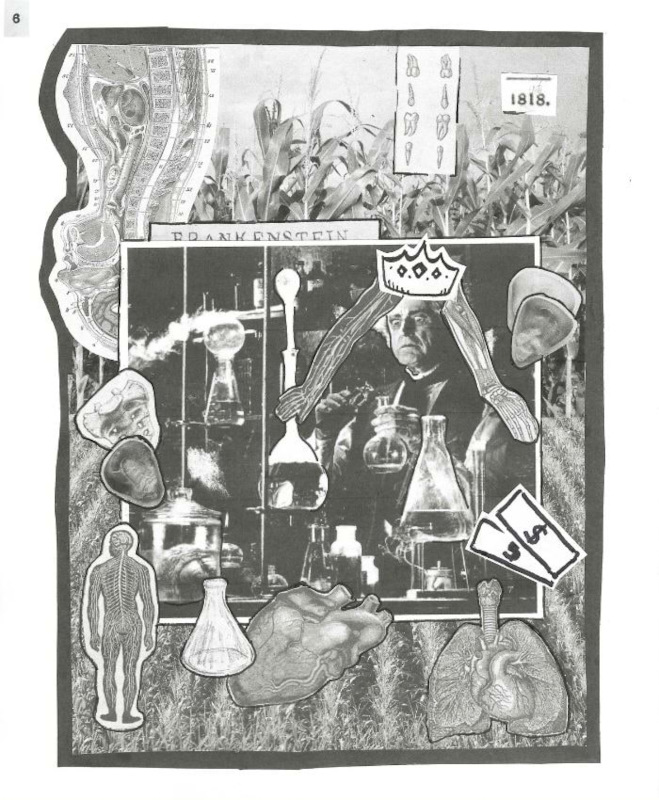

Collage featuring the scientist and his god complex, alongside fractured laboratory. Created by the author.

By heeding Shelley’s call to investigate the inventor’s pride and ambition, we uncover striking parallels between Victor Frankenstein and the pursuit of GMOs in agriculture. Yet, Shelley also instructs us to interrogate the systems that surround the scientist. To fully apply the warning from Victor Frankenstein’s laboratory to modern agricultural biotechnology labs, we must examine the specifics of the setting in which genetic modification technologies are formed.

In the text, Shelley provides a thorough critique of Victor’s isolation—both social and environmental—during his invention process. As Victor Frankenstein travels to university, he reflects somberly on the solitude that awaits him: “I threw myself into the chaise that was to convey me away and indulged in the most melancholy of reflections. I, who had ever been surrounded by the most amiable companions […] I, was now alone” (Shelley 2012 [1818], 46). At university, he descends into a solitary and obsessive pursuit of scientific discovery. His isolation leaves him unchecked, with no one to caution him against the consequences of his pursuits.

During a later journey, Victor is struck by the power and beauty of nature, describing its healing powers with reverence and reflects that “these sublime and magnificent scenes afforded me the greatest consolation I was capable of receiving” (Shelley 2012 [1818], 99). Throughout the novel, encounters with the natural environment continue to offer him brief moments of humility, clarity, and peace—feelings that dissipate when he is confined to the lab. Crucially, Victor’s spatial separation from nature also leads him to create something that is fundamentally misaligned with its balance. As soon as Frankenstein sees the grotesque form of the monster among the beauty of the world, he realizes that it should never have been created. While some critics cite the role of inherent unpredictability and natural forces in the invention’s disastrous outcome, Shelley’s articulate portrayal of Victor’s isolation in the laboratory is a clear caution against pursuing innovation in isolation from social and ecological systems.

Similar to Frankenstein’s monster, genetically modified crops are born as decontextualized entities, disconnected from the environments they are meant to inhabit. Unlike seeds adapted through generations of reciprocal relationships with land, GMOs emerge from a process of extraction. Aaron Eddens investigates this exploitative history by articulating how, during the first Green Revolution, American scientists collected seeds from smallholder farms in Mexico, often without consent (2024, 63). These seeds embodied centuries of careful cultivation and cultural knowledge, yet were appropriated to produce hybrid and, later, genetically modified varieties. Today’s patents turn these same seeds—once freely shared within communities—into private property, severing them from their ecological and cultural roots. Engineered in sterile laboratories, they mirror the isolation of Victor Frankenstein’s workshop. And as with Victor’s creation, introducing these inventions into living systems has unleashed consequences that are profoundly destructive.

Vandana Shiva, in Monocultures of the Mind, discusses some of the environmental consequences caused by the insertion of these technologies, showing how high-yield or “high-response” varieties—GMO seeds designed to withstand intensified chemical inputs—bypass natural checks and ecological limits. By making crops resistant to potent herbicides like glyphosate, biotechnology companies have enabled the widespread, routine use of toxic chemicals. The consequences are catastrophic. In 1990, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that pesticide exposure poisoned an estimated 385 million farmers annually, leading to roughly 200,000 deaths per year. Shiva (1992, 124) discusses how, in the Indian province of Punjab, the use of pesticides has increased the prevalence of cancer to such a high degree that there is a “cancer epidemic.” The train running from Punjab’s agricultural lands to the city of Rajasthan has been dubbed the “cancer train” because its primary use has become transferring cancer patients from the countryside to the city hospital. And this is only part of the cost; pesticide runoff pollutes waterways and destabilizes ecosystems, poisoning human and non-human organisms alike. Just as Frankenstein’s monster unleashed violent consequences beyond the confines of the lab, so too have these biotechnologies—creating systemic damage to ecosystems and communities far beyond their point of origin.

Conclusion

To describe genetically engineered crops as “franken-foods” is not merely to scorn the dangers posed by genetically modified crops. Instead, it is to indict the self-serving ambitions that drive their creation, the imperial mindset that justifies their spread, and the ecological negligence that renders them destructive. Shelley’s novel does not teach us to fear knowledge but to fear what humans become when we forget our responsibilities to each other and the world around us. Monsters and franken-foods are not born—they’re made by human ambition, greed, and ego left unchecked.

Footnote

[1] The novel’s name has further critical implications: the subtitle refers to the Greek myth of Prometheus, who stole fire to empower humanity, with impacts for both himself and mankind. The story emphasizes the ultimate responsibility of those who introduce new technologies, because fire—like any invention or tool–is inanimate and has no motive, moral compass, or foresight. It is Prometheus, his name meaning “one who thinks ahead” who is accountable

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Tayeba Batool and reviewed by Contributing Editor Srishti Sood.

Works Cited

Lewis, Paul. “Mutant Foods Create Risks We Can’t Yet Guess; Since Mary Shelley.” The New York Times, 16 June 1992. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/16/opinion/l-mutant-foods-create-risks-we-can-t-yet-guess-since-mary-shelley-332792.html.

“UN Human Rights Experts Call for Global Treaty to Regulate Dangerous Pesticides.” UN News, 7 Mar. 2017, https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/03/553852.

1 Comment

Well thought out and written. I wonder if leaders and scientists in agribusiness could read this without being defensive. The pesticide implications are shocking. Much gratitude to the author!