Over the past several years, menstrual and hormonal cycles have gained significant public attention across the US and Europe, concurrent with growing skepticism towards biomedicine and an idealization of the natural. From widespread rejection of hormonal contraceptives in favor cycle-based fertility tracking, to satirical social media trends around hormonal cycles, discourses around menstruation reflect a broader zeitgeist around naturopathic wellness. A constellation of women’s health advocates, right-wing influencers, and lay experts have helped to proliferate negative information around hormonal contraceptives, including testimonials about side effects and doubts about their safety. This has unfolded alongside a renewed embrace of non-pharmaceutically suppressed menstruation.

Hormonal contraceptives have long been upheld as the solution to menstruation-related disorders, spurring feminist responses that problematize how menstruation is pathologized and subsequently suppressed. I assert that notions of hormonal health, evaluated through the “normal” menstrual cycle, are negotiated, sustained, and made legible through reproductive politics. In what follows, I draw from critical scholarship on hormones, menstruation, and contraceptives to explore how hormones have been used to regulate and pathologize people who menstruate. Hormonal contraceptives are a gender-, pain-, and autonomy-affirming technology, as are non-hormonal alternatives such as cycle tracking.

Hormone practices and regimes

Hormonal contraceptives suppress the menstrual cycle by introducing exogenous estrogen and progesterone into the body. This inhibits ovulation, blocks sperm by thickening the cervical mucus, and causes endometrial changes that prevent embryo implantation (Ford et. al. 2024, 206). Commonly prescribed to lighten menses and reduce premenstrual symptoms, hormonal contraceptives have not only expanded women’s reproductive and sexual agency, but have also emancipated women and people with uteruses from somatic period pain and social stigma. These menstrual suppression regimes are at once sites of liberation and of biopolitical control.

Feminist historiographers point to the eugenic violence involved in hormonal contraceptive development, a legacy that haunts triumphalist narratives of the reproductive rights movement. In the 1950s, biologist Gregory Pincus and obstetrician John Rock tested the first US birth control pill on non-consenting women in Puerto Rico, using their bodies as testing grounds for dangerous and fatal pharmaceutical trials. Later, in the 1990s, Black and Brown women were targeted for bacterial infection-causing IUDs and questionably developed arm implants (Roberts 1997). The racialization of contraceptive regimes was apparent in how long-acting reversible contraceptives was administered to minority women, while premenstrual tension-fixing pills were marketed to higher-status women to “treat” their premenstrual symptoms (Mamo and Fosket 2009, 941). Lisa Raeder calls this association of moodiness with feminized sex hormones a “gendered molecularization of affect” that subjects menstruators to “normative management practices.”

Alarm clock for the use of birth control pills, 1973. Courtesy Nationaal Archief Netherlands via Flickr Commons.

Cultures of menstrual positivity have responded to entrenched menstrual stigmas in a variety of forms, including menstrual celebration campaigns, woman-led period self-help materials, and a growing awareness of menstrual cycle phases.

The new right and populist hormone discourses

These strains of contraceptive distrust and menstrual positivity have been co-opted by the Trump administration’s MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) campaign, an outgrowth of the MAGA movement led by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. MAHA abuses the genuine moral ambiguity that surrounds pharmaceuticals to advance a conservative pronatalist agenda. As the Trump administration actively dismantles family planning programs and continues to criminalize abortion, they claim to provide accessible fertility awareness education and IVF. This has “reallocated Title X funds for contraceptives to ‘infertility training centers’ that push ‘restorative reproductive medicine and place the blame for the declining birthrate squarely on women’” (Valderrama 2025). Meanwhile, conservative influencers are fearmongering campaigns against “poisonous” birth control. Villainizing the companies that produce contraceptives is a tactical smokescreen for controlling women’s bodies and limiting their reproductive autonomy.

MAHA aims to promote a fabricated tradition of white nationalism, propagated by the idealization of female domesticity. This imaginary is bolstered by fears of hormonal “imbalance,” in which the body is polluted by the “wrong” hormones– an assumption grounded in closely held beliefs about the binary nature of sex. MAHA’s preoccupation with perceived synthetic “toxins” lays bare a panic around threats to the national body, informed by logics of white, hetero, and cisgendered purity, window-dressed as health. In recent months, investigative journalists have extensively reported on the young-adult women trading their birth control prescriptions for app subscriptions. One woman interviewed for a New York Times article learned about “seed cycling”—the practice of eating different seeds at each stage of the menstrual cycle—from her favorite blog. Already dubious about her birth control, she was inspired to ‘take back’ her cycle, enrolling in a fertility awareness course. “I know mentally today I feel better not putting something artificial in my body all the time,” the interviewee said.

What lies at the core of this discomfort around artificial hormones? Estradiol has been associated with increased risks of blood clots, cancer, stroke, as well as more quotidian side effects like headaches and nausea (Gunter 2024). But conservative news outlets have also attached contraceptives to heterosexual desire, claiming that birth control makes women less attractive, and less attracted to fit male partners. Right-wing preoccupations with hormonal contraceptives equate ovulating regularly—which contraceptives inhibit—to “natural’ womanhood, insidiously assigning menstruators a natural destiny of pregnancy and traditional gender roles. This sustains gender oppression, keeping intact a violent binary that ignores the existence of queer people and enforces white Christian nationalism. Panic around hormonal changes implies a “conservative or even a far-right dominant political ideology,” (Wibke Straube cited in Ford et al 2024, 83).

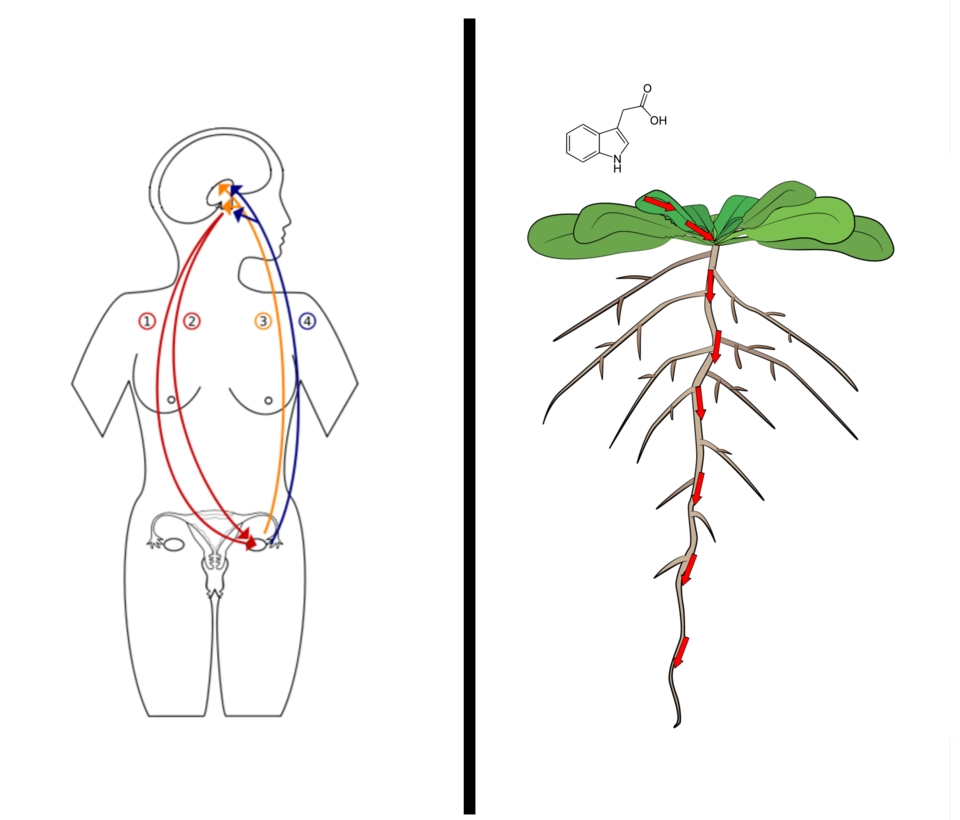

An illustration compares the movement of hormones through humans and plants. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

On the one hand, this growing attention towards menstruation–enfolded into a skepticism of menstruation-suppressing hormonal contraceptives–offers the potential to promote the health and well-being of women and people who menstruate. On the other hand, it signals that society has metabolized the pronatalist and sex-essentialist ideologies broadcasted by conservative politics. When menstrual health is conceptualized as natural, regular, and inhibited by artificial hormones, the menstruating body is upheld as fertile and feminine, making gender normativity and reproduction seem like a given. Critical studies of menstruation and hormones sit at an uncomfortable juncture, where they must challenge threats to reproductive autonomy, but doing so now seemingly entails ‘taking the side’ of biomedical authority, its traditional antagonist. Ultimately, the weaponization of hormonal contraceptives is imbued with neo-feminist rhetoric that fails to acknowledge the importance and value of reproductive decision-making.

Menstrual positivity and hormonal awareness, when enacted through merely individual responsibilities of refusing hormonal contraceptives, perpetuates political control over reproduction. Whereas menstrual suppression was purported as “modern and urban” practice, according to Emilia Sanabria’s ethnography of hormone use in Brazil (2016), menstrual celebration responds to this previous culture of menstrual stigma without calling attention to period injustice, period poverty, or period trauma (Pryzbolo 2025, 16). In either case, menstruating bodies are depicted as having too little or too much estrogen and progesterone. The menstrual cycle is a proxy through which menstruators “ought” to function, behave, express sexual development, and reproduce. Hormones–particularly estrogen and progesterone–are an object through which people try to naturalize culturally constructed meanings of gender and sex, which reifies bio-essentialism and maintains control over menstruators (Ford et. al. 2024). Women and people with uteruses will never menstruate (or not menstruate) their way out of systemic oppression and misogyny. In short, menstruation is a double-edged sword, where both menstrual suppression and menstruation celebration demand that women optimize their hormones and discipline their bodies.

Conclusion: towards a menstrual justice

Menstruation is having a moment. How can this support menstrual health and well-being without contributing to reproductive control? Scholars advocate for increased knowledge production around how experiences of menstruation vary across individuals, groups, global regions, cultures, and lifestyles. App-based cycle tracking, anthropologist Lauren Houghton and data scientist Noémie Elhdad argue, offers a promising opportunity to record data that has previously been neglected in research on menstruation and hormone cycles (cited in Bobel et al 2020). Biomedical researchers have called for physicians to include menstruation, an “underused but powerful tool,” as a vital sign—much like blood pressure, height, and weight—in clinical practice (Rosen Vollmar et al 2025). Cycle tracking can be an empowering tool, especially when used in conjunction with clinical care. Menstruation is increasingly being considered as a marker of health, and period tracker apps have amassed menstrual cycle data, allowing individuals and researchers alike to recognize trends, variance, and other information about this historically stigmatized bodily function (Hohmann-Marriott et al 2023).

Rather than becoming appropriated by ultra-right pronatalism, non-hormonal ways of managing menstruation and fertility should be considered as one element of reproductive and sexual healthcare services, which must also include abortion, contraception, STI and HIV care, infertility treatment, maternal and infant care, and gender affirming care. While the movement against birth control has paid much attention to the side effects to these menstrual suppressing drugs, it has lost sight of the benefits of contraceptives, including but not limited to: reducing the risks of ovarian cysts, treating endometriosis, and combating PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). Ironically, birth control pills are also prescribed to de-masculinize people with PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome) by reducing testosterone over-activity; this fact alone disputes the fallacious idea that pills hinder “natural” womanhood (Gunter 2024). Overall, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to managing the menstrual cycle. Those interested in its fascinating process can share, learn, and support different ways of (not) menstruating so that everyone is equipped to manage their menstruation in any way they choose.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Aaron Neiman.

Editor’s note: An edit was made to the text version of this post to correct a factual error about the Dalkon Shield IUD. The audio version was recorded prior to this text edit and does not include this correction

References

Ford, Andrea, R. Malcolm, S. Erikainen (Anthology Editor), L. Raeder, C. Roberts. Hormonal Theory: A Rebellious Glossary. Bloomsbury Press.

Gunter, Jen (2024). Blood: The Science, Medicine, and Mythology of Menstruation. Penguin Random House.

Hohmann‐Marriott, Bryndl, Tiffany Williams, and Jane Girling. 2024. “Fertility and Infertility Uses of Menstrual Apps from the Perspectives of Healthcare Providers and Patients.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 64 (3): 252–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13781.

Mamo, Laura, and Jennifer Ruth Fosket. 2009. “Scripting the Body: Pharmaceuticals and the (Re)Making of Menstruation.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 34 (4): 925–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/597191.

Pryzbolo, Ela (2025). Ungendering Menstruation. University of Minnesota Press.

Roberts, Dorothy E. 1997. Killing the Black Body : Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

Rosen Vollmar et al, Ana K, Shruthi Mahalingaiah, and Anne Marie Jukic. 2025. “The Menstrual Cycle as a Vital Sign: A Comprehensive Review.” F&S Reviews 6 (1): 100081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xfnr.2024.100081.

Sanabria, Emilia (2016): Plastic Bodies: Sex Hormones and Menstrual Suppression in Brazil. Duke University Press.

Valderramma, Rosa. 2025. Birth Control Fear-Mongering Prevents Women From Achieving Informed Bodily Autonomy. Ms.