Since my undergraduate days, I’ve both aspired to do feminist anthropology and been fascinated with people’s everyday engagement with mundane (and extraordinary) technologies. I can’t express how thrilled and honored I am to receive the 2013 Diana Forsythe Prize for The Life of Cheese: Crafting Food and Value in America (University of California Press), my ethnography of American artisanal cheese, cheesemaking and cheesemakers. I do not present a summary of the book here (if interested, the Introduction is available on the UC Press website: http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520270183). Instead, I alight on some of the STS-related themes that run throughout my book (and especially Chapter 6): regulating food safety and promoting public health, artisanal collaboration with microbial agencies, and the mutual constitution of production and consumption.

Real Cheese or Real Hazard — or Both?

By U.S. law, cheese made from raw (unpasteurized) milk, whether imported or domestically produced, must be aged at least 60 days at a temperature no less than 1.7˚C before being sold. The 60-day rule intends to offer protection against pathogenic microbes that might thrive in the moist environment of a soft cheese. But while the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) views raw-milk cheese as a potential biohazard, riddled with threatening bugs, fans see it as the reverse: a traditional food processed for safety by the metabolic action of good microbes—bacteria, yeast, and mold—on proteins and carbohydrates in milk. The very quality that gives food safety officials pause about raw-milk cheese — that it is teeming with an uncharacterized diversity of microbial life — makes handcrafting it a rewarding challenge for artisan producers, and consuming it particularly desirable for gastronomic and health-conscious eaters, drawn to its purportedly “pro-biotic” aspect.

I have introduced the notion of microbiopolitics as a theoretical frame for understanding debates over the gustatory value and health and safety of cheese and other perishable foods.[i] Calling attention to how dissent over how to live with microorganisms reflects disagreement about how humans ought to live with one other, microbiopolitics offers a way to frame questions of ethics and governance. The U.S. American revival of artisanal cheesemaking and rising enthusiasm for raw milk and raw-milk cheese exemplifies microbiopolitical negotiations between a hyper-hygienic regulatory order bent on taming nature through forceful eradication of microbial contaminants — a Pasteurian social order (as currently forwarded by the FDA) — and what I have called a post-Pasteurian alternative committed working in selective partnership with ambient microbes.

As Bruno Latour relates in The Pasteurization of France, in recognizing microbes as fully enmeshed in human social relations, early Pasteurians legitimated the hygienist’s right to be everywhere; once microbes can be revealed in the lab (Pasteurians continue to believe) they may be eradicated — only then will “pure” social relations be able to flourish. In contrast, post-Pasteurians move beyond an antiseptic attitude to embrace mold and bacteria as potential friends and allies. The post-Pasteurian ethos of today’s artisanal food cultures—recognizing microbes to be ubiquitous, necessary, and even (sometimes) tasty—is productive of modern craft knowledge and expanded notions of nutrition, and it produces a new vocabulary for thinking about conjunctures of cultural practice and agrarian environments, along the lines of what the French call terroir.

I want to be very clear: some bacteria and viruses make some people sick, something no food-maker wants to risk. Successful post-Pasteurian food-makers are never cavalier about pathogenic risk. Dairy farmers who trade in raw milk and cheesemakers who work with it are exceptionally careful about hygiene—they are not anti-Pasteurian. To the contrary, they work hard to distinguish between “good” and “bad” microorganisms and to harness the former as allies in vanquishing the latter. Post-Pasteurianism takes after Pasteurianism in taking hygiene seriously; it differs in being more discriminating.

Focused on the aggregate of national population, Pasteurian microbiopolitics has been criticized for taking a one-size-fits all approach to food safety, predicating regulation on industrial-scale production (relying on pasteurization or irradiation to kill pathogens presumed to be present owing to insanitary agricultural practices) and population-wide consumption (young raw-milk cheese is forbidden to all because it carries particular threat to immunocompromised and pregnant consumers). Post-Pasteurians counter that fresh milk is not inherently “dirty” and in need of pasteurization; contamination is a matter of human agricultural practice, it is not in the “nature” of milk. Moreover, many assert that the heterogeneity of the public in “public health” should not be reduced to its lowest common denominator; people are individuals. In other words, the post-Pasteurian position lobbies for socio-legal latitude that would permit potentially risky foods to be made and consumed safely by some, if not others.

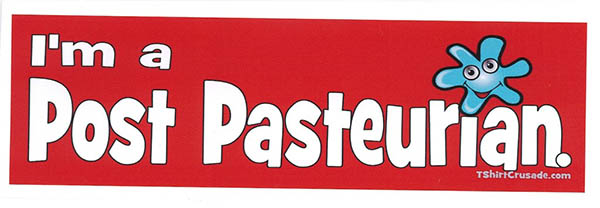

I worry, though, that as enthusiasm for the beneficial agencies of microorganisms grows, underinformed enthusiasts may overestimate the power of “nature’s” microbial goodness.[ii] I fret even more when such a position is characterized—as I am beginning to see—in terms of “post-Pasteurianism.” Last year I discovered for sale on the Web t-shirts, bumper stickers, even maternity shirts and baby bibs emblazoned with a smiling microbe and the slogan, “I’m a Post Pasteurian.”

Descriptive copy explains, “What is a ‘Post Pasteurian’? A really smart person who understands that pasteurization kills all (yes, ALL) the good in food.”[iii] This is not how I defined “post-Pasteurian” in my 2008 article or 2013 book. For the record, I refuse the claim. Pasteurization does not “kill” all the good in food. The position putatively espoused by the t-shirt would pit a beneficent “nature” supernaturally enlivened by microorganisms against a power-greedy “culture” championed by regulatory overreach. But the natural-cultural reality is that milk and fermented foods such as cheese, yogurt, miso, and beer are multispecies muddles that resist such simplistic parsing.

There’s nothing essential about a food’s goodness. Humility is required to navigate (not necessarily manage, let alone steward) post-Pasteurian microbial ecologies.

By “microbiopolitics,” then, I mean to describe and analyze regimes of social management, both governmental and grassroots, which admit to the vital agencies of microbes, for good and bad. Including beneficial microbes like starter bacterial cultures and cheese mold — in addition to the harmful E. coli, Lysteria monocytogenes, and Micobacterium tuberculosis — in accounts of food politics extends the scaling of agro-food studies into the body, into the gastrointestinal. “Microbes connect us through diseases,” writes Latour, “but they also connect us, through our intestinal flora, to the very things we eat.”[iv] At the beginning of the twenty-first century, as it comes to light that 90 percent of what we think of as the human organism turns out to comprise microorganisms, the truism, “We are what we eat,” has never seemed more literal. One aim of my work has been to show how artisan food-makers carefully sort out microbial friends from foes, work (not faith) that produces the conditions through which a post-Pasteurian dieticity might safely emerge—for some if not others.

[i] See Heather Paxson, “Post-Pasteurian Cultures: The Microbiopolitics of Raw-Milk Cheese in the United States,” Cultural Anthropology 23(1): 15-47, 2008. And also Heather Paxson, The Life of Cheese: Crafting Food and Value in America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

[ii] See also Gareth Enticott, “Risking the Rural: Nature, Morality and the Consumption of Unpasteurized Milk,” Journal of Rural Studies 19(4): 411-424, 2003.

[iii] Available at TShirt Crusade and the libertarian emporium, Liberty Buys. Accessed June 26, 2012.

1 Trackback