Editor’s note: This week, we have a first for the blog: a bilingual post!

“When I first started to come out as trans, I went straight to YouTube, and watched a bunch of videos trans kids, and then I started to find videos from people my own age.” Sitting in the living room of his parents’ house in suburban Santiago, Chile, days before his double mastectomy in June 2016, Noah told me a story I would hear repeatedly, with surprisingly little variation, over the course of my fieldwork. He continued, “Even then, the reality I saw was very different. The majority were from the US and England, but at least they helped me understand, ‘OK, so you can start to transition at the age of 19 or 20, like me.’” After an adolescence of not knowing quite where he fit, Noah had found a global community of people like himself with the click of his mouse.

In Chile, where a draft Gender Identity Law has languished in congress for four years, trans people are afforded little to no protection under the law (Miles 2013), and trans-specific healthcare is certainly not traditionally covered by the country’s healthcare system. Add to this the increasing disparity between the public and private healthcare systems combined with a working-class background like Noah’s, and the road to physical transition—endocrinologist and psychiatrist visits, regular hormone injections, surgical intervention, and legal fees, among others—can seem impossible for the majority of trans people in Chile. Though several NGOs have emerged in the last few years to help those who wish to transition, many trans Chileans feel isolated and unsure what their next step should be. Enter social media.

Though he felt he had found a new online community in YouTube, Noah was lucky to have a good command of the English language. “I said, well this is great for me, because I understand a lot of English. But what are other people doing? I looked and looked, and I only found one channel, by a Mexican guy. He was middle class, had to work to pay for school; his reality was a lot closer to mine. That’s when I decided to start my own channel.” Noah’s desire to make his own videos reflects a lack of visibility of trans realities produced by and for trans people in the global south. Given the importance of these technologies to young, isolated trans people—many of whom first discover online that other trans people even exist—this is an important deficiency, and one that is increasingly being addressed by members of Chile’s trans community.

I don’t identify as a man, I don’t want to look like a man, so, what am I?

Although trans issues in Chile, as in the US, have gained a great deal of attention in the last five to ten years, the average cisgender Chilean (and US citizen) is ill-equipped to speak to trans people about their specific experiences. And while trans activists in Chile have been very successful in inserting trans issues into the public the discourse, the general public’s understanding of “a man who wants to be a woman” or vice versa, is woefully undernuanced. It relies on a rigid understanding of the gender binary, especially difficult to question in Chile, where machismo reigns supreme (Olavarría and Moletto 2002.) Increasingly, the average Chilean seems slightly more comfortable with transition from one fixed gender category to the other, but threats to the gender binary continue to inspire confusion and disgust. This is perhaps most clear in the pending Gender Identity Law, which would—if passed—provide for legal gender transition, but only between male and female categories.

Nonetheless, Noah’s YouTube channel is purposefully called “Female to Noah.” Though he prefers masculine pronouns, Noah identifies as transmasculine non-binary—that is, as neither a man nor a woman, but toward the masculine of the spectrum—an option he didn’t even know existed until he saw a video on YouTube. “When I would search online I would say pucha (dang), I don’t identify as a man, I don’t want to look like a man, so, what am I? But then all of a sudden, I found this video of two gringos, two chicxs (young people, gender neutral), who were assigned female at birth, and said they identified as transmaculine non-binary. And I was like…what?” This was a watershed moment for Noah. Growing up isolated from other trans people, it was YouTube that give him a name for who and what he always felt he was. Finally having a name to attach to his identity gave him both a political subjectivity and a clear path forward, as he began to change his exterior self to match his interior: not a woman, masculine, but not a man.

The Where and When of Trans Bodies Online

Though at first blush perhaps counterintuitive, trans social media use is intimately tied to the body. Rather than reducing the body simply to an abstraction, a human behind a keyboard or in front of a camera, my interlocutors use the capabilities afforded by social media technologies to inhabit and perform fleshy, embodied identities, complete with cellulite, scars, and surgical drains. They track their transitions, applying laser focus to the hair follicles of their nascent beards, or to the barely perceptible swelling of long desired breasts. These transition videos are one of the most popular, almost archetypal, kinds of trans social media activity. The visual and temporal specificities of social media allow trans people to create a living, public archive of their transitions, consisting of coming out videos, visits to doctors, hormone injections, and bodily progress reports. Furthermore, they have a pedagogical element, serving as examples for people who are considering transitioning, or just beginning. They are a sort of accidental how-to guide.

“NOAH//FTM Chile – 2 years on testosterone”

I should underscore here that the interlocutors discussed in this post are transmasculine (feminine to masculine); this is not an accident. The “community standards” of platforms like Facebook and YouTube make it almost impossible for transwomen to engage in the same type of online behavior as transmen. As flat, masculine chests become feminine breasts, transwomen find that their bodies are no longer acceptable for public display, and their social media posts are often reported, censored, and taken down. Conversely, transmasculine interlocutors find themselves with a new sense of bodily autonomy. One of the most common desires of my transmasculine interlocutors is “to go the beach with my shirt off.” Similarly, these same interlocutors find that—after their mastectomies—they no longer have to cover their nipples in their YouTube videos and Facebook posts, greatly facilitating the production of web content.

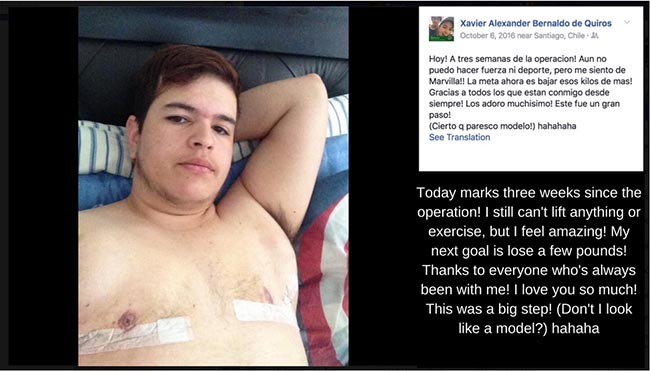

Another interlocutor, Xavier, documents the progress of his transition on Facebook

This meeting of technology and the trans body not only puts trans bodies on display, it conjures a queer time that overtly questions hetero- and cisnormative temporality—one based on the perceived normalcy of the choices of heterosexual, cisgender people—locating the march of time instead in the trans body (for a much more nuanced discussion than I have space for here, see Tobias Raun’s superb article [2015]). The beginning of transition sets a process in motion, but one whose telos is unclearly defined. Hair follicles, mammary glands, and voice cracks become de facto chronometers, marking with each minute change a step forward. The body is, for its part, unpredictable, reticent to conform to the hegemonic expectations placed upon it. No two bodies will react the same to testosterone or estrogen therapy. Some may grow or lose a beard in a matter of months, while the genetic lottery may forever deprive others of the thick full beard or smooth soft face they desire. Social media itself thus becomes both timekeeper and judge, preserving a bodily archive of what the body once was, and ostentatiously displaying on the bodies of others what one’s own body might one day be.

Social media technologies have undoubtedly changed the very meaning of what it is to be trans in Chile, and perhaps globally. Especially in the Global South, as Internet access becomes more and more ubiquitous even among the disadvantaged (Statista 2014), access to social media has become a crucial tool, for pedagogy, subjectivization, and community building (Haynes 2016.) Where once young trans people often lived in silence and fear, they increasingly can find both community and resources in Facebook posts and YouTube videos from Chile and around the world. Nonetheless, these same often-emancipatory tools create, foster, and reify hegemonic bodily and temporal expectations that may be unrealistic and even harmful. The realities they reveal underscore the racialized and classed disparities in access to healthcare, the linguistic barriers that separate queer people in the Global South from a larger, Anglo-centric LGBTQ movement, and the raced and gendered expectations for performing embodied gender “acceptably.” Nonetheless, the same global forces that allow for a British video to be seen by a young trans Chilean offer enticing possibilities. Access to social media is allowing trans Chileans to tell their own stories, speak back to power, and help to write a new script for those who will follow in their footsteps.

Author’s note: All material taken from social media has been with the express consent of the interlocutors in question, for which I am deeply indebted. The screenshot and translation are my own. I am also grateful to Víctor Giménez Aliaga for his help in copyediting the Spanish version of this post.

References Cited

Haynes, Nell. 2016. Social Media in Northern Chile: Posting the Extraordinarily Ordinary. London: University College London Press.

Miles, Penny. 2013. “ID Cards as Access: Negotiating Transgender (and Intersex) Bodies into the Chilean Legal System.” In Situating Intersectionality: Politics, Policy, and Power, edited by Angelia R Wilson, 63–88. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Olavarría, José, and Enrique Moletto. 2002. Hombres, identidad/es y sexualidad/es : III Encuentro de Estudios de Masculinidades. Santiago, Chile: FLASCO-Chile : Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano : Red de Masculinidad/es.

Raun, Tobias. 2015. “Archiving the Wonders of Testosterone via YouTube.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 2 (4): 701–9.

Statista. 2014. “Active Social Media Penetration in the Americas 2014.” Statista.com. https://www.statista.com/statistics/214690/social-network-usage-penetration-of-the-americas-online-populations/.

1 Trackback