I was only a couple of months into my fieldwork when I met Masa. I had been focusing my attention on innovation and politics within the major Japanese TV networks, but he drew my attention to a different kind of media organization: The Free Press Association of Japan, now defunct. At the time, he identified with its founder, Takashi Uesugi, who had made a name for himself as one of the country’s most prominent crusaders for Japanese journalism reform.

Masa liked anyone who flouted convention, and the mainstream media’s disparagement of Uesugi for not having attended a high-ranked university only served to endear him further to Masa, who himself had not attended college. It was from Masa that I first heard about chemtrails (kemutoreiru) – the notion that the white trails that aircraft leave in their wake represent a chemical form of meteorological or biological manipulation. He began forwarding me articles and links to documentaries exposing Japanese and American government cover-ups. Unemployed, he spent most of his days on the Japanese bulletin board, 2ch (ni chan). He was my first encounter with the Japanese internet alt-right (the netto uyoku), the beginning of an inadvertent deep-dive into one of the most vocal factions in the Japanese internet.

In this piece, I move to expand a general anthropology of hackers, trolls, and the political right into East Asia, as the beginning of a discussion about the role of technology in extremist politics there. Although the right-wing has been an object of study there (for a captivating account of one feminist anthropologist’s work on the far-right, see Tomomi Yamaguchi’s essay “Impartial Observation“), the political climate of 2017 makes understanding xenophobic, sexist, and homophobic internet spaces all the more relevant.

That the alt-right became such a topic of interest to the American media as our own presidential election season unfolded felt to me like deja-vu. I had been in the room when Shinzo Abe was re-elected Prime Minster, amidst an exhausting year in which they’d turned on the FPAJ and Takashi Uesugi, and nearly single-handedly brought down that organization. In the U.S., the alt-right was given at least partial credit for Trump, and journalists rushed to cover the topics of trolling, alt-right Twitter, reddit, and 4chan (the English language counterpart of the original Japanese 2chan). Media scholars, in turn, stepped in to debunk and comment on the amount of credit these groups were given for driving politics, but their arguments were largely lost in the din.

In Japan, the very mention of 2ch tends to elicit sighs and eye-rolling from most journalists, who resent how the site’s anonymity exposes racist (particularly anti-Korean), nationalistic, and conspiratorial sentiments lurking within Japanese society. The site is so known for its racism that a 2010 Korean cyber-attack targeted 2ch specifically, and protests against racism (Tokyo 2013, for example) highlighted the site’s role in fostering this sentiment.

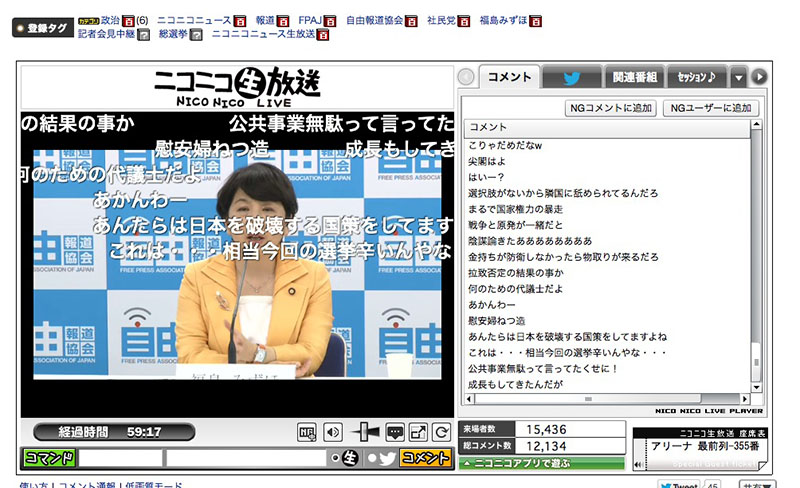

In 2012-2014, the ethos of 2ch seemed to be everywhere in Japan. Popular website Nico Nico Douga, which allows users to type comments that display over streaming videos, was often a hotbed of comparable rhetoric– so much so that I had trouble finding a single screen capture from those I’d taken at FPAJ press conferences that didn’t contain racist, sexist, and otherwise far-right political statements. Americans were another common target, particularly our occupation of Okinawa and the incidents (both real and exaggerated) of violence against Okinawan women.

The Nico Nico Douga interface during a Free Press Association of Japan press conference. Copyright author.

While I want to be careful to not equate one with the other, it is clear that overlaps do exist between the netto uyoku and the American alt-righters, and that these overlaps can also be extended to other parts of the world where prominent right-wing movements have influenced mainstream political discourse (Brexit being one example). The right-wing in Japan could easily unite under a banner of Make Japan Great Again, as much of their rhetoric revolves around the notion that immigration has weakened Japan economically, diluted Japanese culture, and diminished its global standing. Although Koreans are to Japan what Mexicans are to America in these political circles, the netto uyoku are also motivated by a desire to minimize the West’s interference in Japan’s political system. That many Americans are unaware of Japan’s retention of its emperor is one symptom of the problem perceived by netto uyoku (and blared from many a uyoku dantai, ring wing propaganda van speaker).

Nationalism in Japan often means advocacy of that country reassuming a form and structure characteristic of the World War II era, with the restoration of the emperor as political head being just one component. Many of the most vocal proponents of ultranationalism are men who grew up in the post WWII era, and whose politics were formed in the post-war, post-Japanese surrender political climate. They want to re-establish an active military. They often feel disenfranchised and left behind in ways that resemble descriptions of Trump voters and extreme right-wingers world wide. And, they rallied behind unapologetic nationalists like former Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara, Tokyo gubernatorial candidate Toshio Tamogami, and current prime minister Shinzo Abe.

But, although Ishihara and Abe in particular resemble Trump demographically, it is perhaps Osaka governor Toru Hashimoto whose rise and transition from businessman to television personality to politician that most resembles Trump’s. It remains to be seen if Hashimoto, founder of his own political party (Nippon Ishin no Kai, or the Japan Restoration Party) is too extreme ever to become Prime Minister, but the energy of his supporters factored into Abe’s election.

A rally for Hashimoto (photo by author)

Hashimoto has been known to make inflammatory and provocative comments about women (such as those about South Korean “comfort women” during World War II), and to attack and attempt to delegitimize the mass media– specifically going after the Asahi Shimbun, one of Japan’s largest and most prominent newspapers (who, it must be noted, have certainly gone after him in the past as well). This paragraph, from an article about Hashimoto by Eric Johnston, might sound familiar:

“There are two fundamental mistakes Hashimoto’s critics make. The first is to assume his words and ideas are merely his own or those of a tiny minority, and do not reflect the views of a growing number of voters who live in the “real” Japan — the one that exists beyond Tokyo’s Yamanote Line[1]. The second is to ignore the fact that Hashimoto’s comments and policies sound like independent populism at times but are often supported, sometimes quietly, sometimes loudly, by powerful members of the economic and political status quo Hashimoto is seemingly bashing.”

When these views cannot be expressed in polite society, as we know, they often manifest online. With a stagnant economy and declining rates of marriage, anomie is an oft-remarked upon characteristic of Japanese social life. Frustrated with the mainstream media and politicians, the anomic, or just plain right-wing, often decry them for colluding with one another, for publishing lies, and for protecting illegal immigrants. A consensus on forums like 2chan is that most news outlets, constrained by political correctness, cannot tell the truth about anything Korean, for example. (Minus the Korea part, the same sentiment is generally shared by the Japanese left-wing.) Indeed, I remember dodging the anti-Korea protests at Fuji TV while I was doing fieldwork there.

Abe was the first national leader to meet with President Trump. But, amidst considerable scholarly and journalistic interest in global alt-right movements, Japan has not played a particularly prominent role in the discussion. This is despite the unique relationship between our two countries, and significant parallels between our online worlds. (Twitter use in Japan is among the highest in the world, and currently one of the faces of alt-right trolling in the U.S. and Japan.) Recently, tensions in North Korea have galvanized certain kinds of rhetoric online, and despite their brand of extremism still representing a minority perspective, the netto uyoku’s response will represent a relevant sociopolitical force.

- This is to say, beyond central, and generally affluent, Tokyo.

1 Trackback