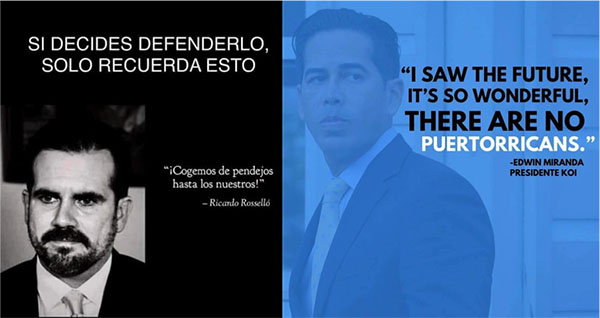

On July 13th, the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (Center for Investigative Journalism) leaked 889 pages of a Telegram App chat between the governor of Puerto Rico, Ricardo “Ricky” Rosselló and eleven cabinet members and aides. The 889 pages were full of misogynist, homophobic, and classist comments about political figures, journalists, artists like Ricky Martin, and average citizens. They mocked the victims of hurricane María, which left 4,645 dead, saying “don’t we have some cadavers to feed our crows?” Memes citing the most egregious statements quickly began circulating through social media alongside early calls for the governor to resign. But beyond such insulting statements, the chat revealed complex corruption schemes and provided evidence of persecution of the governor’s political opponents.

The image on the left reads: IF YOU DECIDE TO DEFEND HIM, JUST REMEMBER THIS. “We even fooled our own people!”

For Puerto Ricans—having lived through an economic crisis that led to the imposition of a fiscal control board by the United States government, massive school closures, and the devastation caused by hurricane María—the leaked chat was a breaking point. Comments from the chat catalyzed the largest protest in modern Puerto Rican history. People on the island and in diaspora came together regardless of political, generational, and social divides to call for the governor’s resignation using the hashtag #RickyRenuncia.

The image on the right reads: “This country endured. It carved pieces of wood to wash clothing, organized food pantries, took care of neighbors, saw their families migrate, buried their dead as best they could. There, in silence, biting their lips. Really, they still do not understand that this scream comes from our viscera?”

You resign on Facebook, I celebrate in the streets

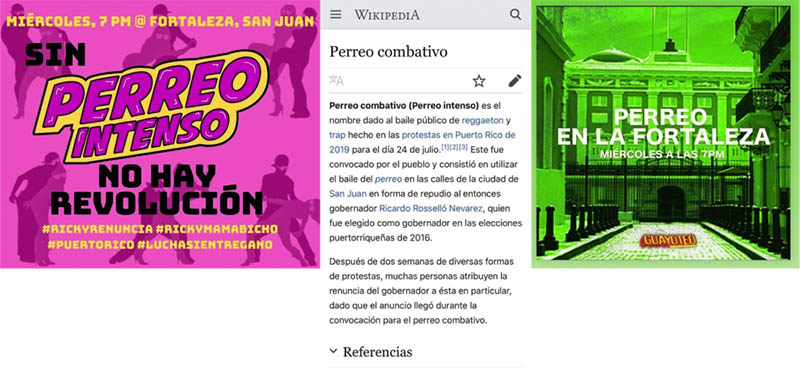

After twelve days of protests, rumors of the governors impending resignation began circulating through social and mainstream media on the night of July 23rd. At 5pm on July 24th, the governor called for a press conference at Fortaleza, the governor’s mansion and site of most protests and police attacks on protesters. Over two hours after the press conference was slated to begin, there was still no news coming from Fortaleza. As the wall of silence and speculation continued, posts on social media indicated that the night’s protest, the Perreo Combativo (a reggaetón dancing protest) would start at 8pm unless the governor gave his official resignation.

On the left, “And nobody wanted to go to bed because the rumor was that Ricky would resign. On the right, “Me here, waiting for Ricky to resign.”

As I waited to meet up with friends to attend that night’s protests, a flurry of social media posts began circulating about increased police presence near the protest. Simultaneously, messages from media outlets announced that the governor had left the mansion. Information, memes, comments, rumors, speculations, and calls to protest circulated non-stop.

Images inviting participants to the Perreo Intenso/Combativo, and a Wikipedia article on the subject.

https://www.facebook.com/sharon.tossas/videos/10157438206650522/UzpfSTUwNzY0MDk0MjoxMDE1NzE2NzQ1ODQ0MDk0Mw/

We never made it to the protest, opting to stay at our meeting point, a small bar in Santurce where a plena group was playing on the street. All their songs called for the governor’s resignation. The air of protest was everywhere, offline and online, near the mass protests or on any street corner, bar or business.

“Oye Ricky Rosselló/ tu renuncia no me importa/ El pueblo es el que gobierna / y es el mismo que te bota.” (Hey Ricky Rosselló/ your resignation doesn’t matter/ the people govern/ and we are firing you.)

The music stopped as we heard the resignation was about to air. Some of us hurried inside the small corner bar which had a large screen TV, while others stayed outside looking for live feeds on their phones. Near midnight, on the eve of the day we celebrate the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the Governor posted a pre-recorded resignation video message on Fortaleza’s Facebook page. Yes, he was resigning over Facebook. Even media outlets were transmitting the pre-recorded message from their own Facebook feeds. As we waited for the two words millions of Puerto Ricans had been clamoring for the past twelve days, the video froze, triggering a mass reaction of frustration inside and outside of the bar. There were too many people streaming the same video from the same Facebook page. The video unfroze seconds before Ricky stated: I resign. People screamed “we did it!” jumped, and hugged friends. Plena music added rhythm to the chants of “renunció” (he resigned). Fireworks appeared in the sky, motorcyclists from the neighborhood started “chillando gomas” (doing burnouts) and the Perreo Combativo turned into a celebration.

As with many contemporary social movements, online activism and digital media were critical for organizing protests, making calls for action, sharing information and personal opinions, politically mobilizing trolling techniques (for more see Coleman 2015), and circulating memes (for more on the Puerto Rican political history of memes see Gil 2018). Social and digital media forms were integral to physical social manifestations that went beyond allowing “users who are territorially displaced to feel like they are united across space and time” (Bonilla and Rosa 2015). Anthropologists looking into digital worlds have called for us to explore the ways in which online and offline realities exist in complex forms of interrelationship (Boellstroff 2016, Miller 2012).

As protests expanded beyond the governor’s mansion into the rest of the island and abroad, demonstrations overtook “digital places,” (Boellstorff 2016) saturating online worlds with calls for Ricky’s resignation. Social media campaigns incited individuals to carry out creative direct actions in the physical world to be shared online, turning individual acts into acts of public protest and fostering participation in ways that included but were not limited to sharing media or taking selfies. The ways in which online worlds can traverse spatio-temporal distances helped expand the reach of protests across geographic areas, time zones, domestic spheres and diverse populations of Puerto Ricans; allowing many in and beyond San Juan to join the creative assemblage of demonstrations. This was all done by politically deploying and exploiting the digital “poor image,” which has the capacity to build new alliances through its circulation, creating new publics and debates that emerge from producers/users/consumers not tied to corporate or state discourses (Steyerl 2009). Here, I will unpack three elements of this protest-assemblage that shows how national creativity in the use of digital and non-digital forms of activism integrated diverse intersectional categories while expanding the reach of protests calling for our governor’s resignation.

We protest on horseback, motorcycle, dancing, in silence and everything is memefied

On July 14th musicians Ricky Martin, Bad Bunny, and Residente announced via social media they were joining the ongoing protests. Posts about demonstrations on the 15th and 22nd of July quickly changed to include information about the presence of these celebrities. Simultaneously, other groups advertised a wide array of actions through social media. Just like many other contemporary social movements—from Occupy to the Arab Spring, Ferguson to transportation protests in Brazil—there was no one centralized group or leader organizing or developing activist strategies (Bonilla and Rosa 2015, Stalcup 2016, Tufecki 2018). Motorcycle groups, horseback riders, boat and kayak owners, scuba divers, mothers, cyclists, yoga enthusiasts, and others convened their own demonstrations. Protesters organized a public reading of the 889 chat pages, a public reading of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico in front of riot police who had been violating protestors’ constitutional rights, a silent march to remember and honor those who died due to hurricane María, and dance protests like the Perreo Combativo. Posts for these independently organized protests circulated through social media platforms before being picked up and further promoted and covered by mainstream media. While these protests did not bring together half a million people like the ones on July 15th and 22nd, they helped keep a consistent flow of demonstrations for twelve consecutive days.

Protests and actions were scheduled for all hours of the day, starting at 8 or 9am with silent marches for Maria’s dead or yoga, and ending at 11pm when police would decide that protests had “become unconstitutional” and would begin launching tear gas at protestors. Many of these themed protests coded—some more overtly than others—class, educational, gender, racial, and sexual differences. People who did not identify with these groups nor partook in activities like yoga or boating, would still share information about the events and show up to support, record, and share them online. Sometimes different demonstrations merged, like when 1,500 cyclists arrived at Fortaleza to find protestors reading the Constitution, or when hundreds of motorcycles from the poorest neighborhoods and projects in the greater San Juan area were convened by Rey Charlie to join protestors in old San Juan. Puerto Ricans were able to mobilize their difference politically, allowing and supporting multiple social groups to protest in their own unique ways, creating “an intersectional solidarity in the movement because of the multiple grievances that Puerto Ricans seek to rectify” (Santiago-Ortiz and Meléndez-Badillo 2019). Our difference became a political tool that united a nation under one single claim: Ricky Renuncia.

A few of the wide variety of forms of protest that emerged during #RickyRenuncia

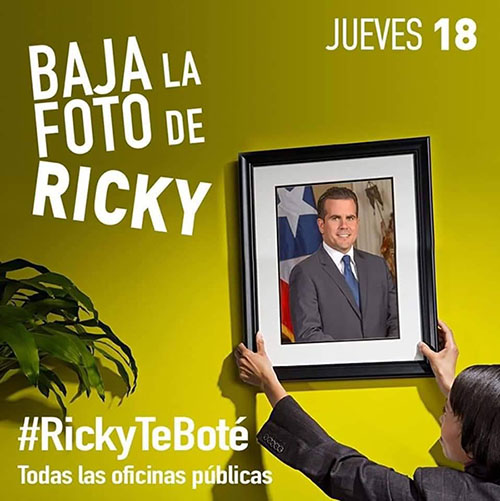

Such creative forms of online organizing extended to direct action campaigns. I will briefly discuss two direct actions that doubled as digital media campaigns: #RickyTeBoté and el Cacerolazo. Both actions/campaigns used digital spaces to extended manifestations into government agencies, inside people’s home and across public spaces throughout the island and diaspora.

“Thursday the 18th, Take down Ricky’s Photo”

Digitizing Direct Actions: #RickyTeBoté and el Cacerolazo

Government agencies in Puerto Rico have a portrait of the current governor on the wall. On July 16th, three retired women took down Ricky’s portrait from the CESCO (Puerto Rico’s DMV.) Police were called to intervene. As the women later stated in various interviews, this action was as a way of making their outrage felt. The video quickly went viral under the hashtag #Rickytebote (which translates to Ricky, I fired you and/or Ricky, I dumped you). A guide for how to take down Ricky’s image from government offices began circulating through social media. The guide recommended that people act in pairs, with someone taking down the portrait and someone recording. Recording the action served a multiple purpose: to document and make visible an act of individual protest inside government agencies; to expand an online spamming campaign of the governor’s social media and mess with search engine algorithms; and to ensure the safety of those executing the action in case of police intervention. #Rickytebote quickly gained traction as videos circulated of people taking the portrait off the wall in government offices throughout the island and either walking away with it or putting it face down on the floor. Still images showed the portraits in trashcans and the back seat of people’s cars. My father, who is in his seventies and cannot attend large protests due to his health, saw this campaign as a way for someone like him to join the protests and make his indignation felt. He accompanied me on an errand at the Registro Demográfico (Vital Records Office) and suggested that I record him taking the portrait down. But before we arrived, my partner messaged me a Tweet with a photo of the empty wall at the Registro Demográfico; someone had beaten us to it. #Rickytebote not only made visible and public individual actions but extended protests inside government agencies with citizens symbolically removing the governor from his position of power. This direct action also garnered the political participation of people like my father and others across the island who could not physically attend the mass demonstrations. By July 18th, the governor placed police in every government agency across the island to guard his portrait.

L-R: Careful: go with two other people if you can, one to film and the other to mediate if someone tries to stop you; Step #2: Find your closest government office and take down the official portrait of the governor; a portrait of Roselló in a trashcan; The governor’s photo was removed from the Central Registry; three woman take down the governor’s photo; two people show how they feel about the governor’s portrait

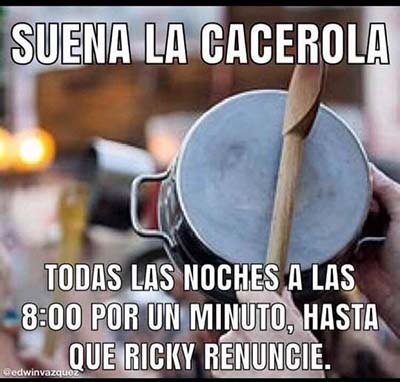

We will bang our pots every night at 8:00 for one minute, until Ricky resigns.

Similarly, the Cacerolazo blurred the line between digital media content and direct protest action. The cacerolazo has a long history within Latin American social movements, calling for people to bang their pots (cacerolas) from their homes at a set time. The aim is to produce sufficient collective sound to occupy public space in situations where regimes did not allow for public protests. Social media posts called for people to bang their pots every night at 8pm. The cacerolazo, an action that emanates from inside people’s homes done with kitchen objects shows how the domestic sphere is a political space. Sound emanating from inside the private sphere out into public areas breaks down the separation between spaces of mass public mobilization and individual domestic manifestations. People throughout the island and diaspora began posting pot banging videos, using sound to occupy places abroad and online. Shared videos showed the noisy chorus of pots coming out of entire buildings resonating at a distance. This sonic demonstration became a daily occurrence. As the cacerolazo continued blurring online and offline space, as well as public and private spheres, this non-digital action turned digital form of protest traveled beyond people’s homes as protestors showed up in public demonstrations with their pots. The image of the cacerolazo as another tool in our social movement arsenal became emblematic with the viral video of Cacerola Girl. The video showed a lone-standing woman banging her pot in front of a large number of police who were in the process of launching tear gas at protestors.

Even though Ricky officially submitted his resignation, demonstrations are far from over. These protests are not just celebrations of our political awakening, but serve as a reminder for politicians that this newly articulated national subjectivity seeks a fundamental political change. On August 2nd, Ricky’s last day in office, a Farewell Party will take place in front of the governor’s mansion. Those who cannot attend can join in by honking their car horns at 5pm. On Monday, July 29 there will be an action to protest the incoming governor, the Secretary of the Justice Department, Wanda Vázquez, who is currently under FBI investigation for corruption. I anxiously wait to see what new forms of protest develop, taking advantage of the unique ways in which digital, online and virtual forms can be politicized and enhance offline social demonstrations.

https://www.facebook.com/elforodepuertorico/videos/215823786009674/UzpfSTUwNzY0MDk0MjoxMDE1NzE3NTk4ODc2NTk0Mw/

L-R: Hit the road, Wanda; You’re invited to Ricky’s Farewell Party; Car horn-athon across Puerto Rico, Friday August 2 at 5:00PM to give Ricky Rossello a proper sendoff.

Perreo combativo, national strike, you who fucking showed up,memes and artists, King Charlie: Captain Puerto Rico

References

Boellstorff, Tom. 2016. For Whom Ontology Turns: Theorizing the Digital Real. Cultural Anthropology 57(4): 387 – 407.

Bonilla, Yarimar and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist 42(1): 4 – 17.

Coleman, Gabriella. 2015. Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous. Verso.

Gill, Caroline. 2018. “La Bola de Cristal”: Puerto Rican Meme Production in Times of Austerity and Crisis. InVisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture 28. http://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/la-bola-de-cristal-puerto-rican-meme-production-in-times-of-austerity-and-crisis/

Miller, Daniel. 2012. Social Networking Sites. In Digital Anthropology, edited by Heather A. Horst and Daniel Miller. Berg.

Santiago-Ortiz, Aurora and Jorell Meléndez-Badillo. Puerto Rico’s Multiple Solidarities: Emergent Landscapes and the Geographies of Protest. Radical History Review. https://www.radicalhistoryreview.org/abusablepast/?p=3152&fbclid=IwAR0SuHTbRyXkZ3nyyh1JxFbvmjeF0x_KOqa0inXOaBJgdn9Dfs8zLyPTYB8

Stalcup, Meg. 2016. The Aesthetic Politics of Unfinished Media: New Media Activism in Brazil. Visual Anthropology Review 32(2): 144 – 156.

Steyerl, Hito. 2009. In Defense of the Poor Image. E-Flux 10: 1 – 9.

Tufecki, Zeynep. 2018. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protests. Yale University Press.

1 Trackback