Eyes in/on/for Hong Kong

At the Hong Kong airport, thousands of protesters line the arrivals hall. Creating a corridor for passengers to walk through, they stand silently, using their right hand to cover their right eye. The silence is occasionally perforated by calls of “Hāng Góng Gā Yáu!” and “Xiāng Gang Jīa Yóu 香港加油 – “Hong Kong Add Oil”— expressions of solidarity and encouragement that have become fuel for protests that have been ongoing and lively since March.

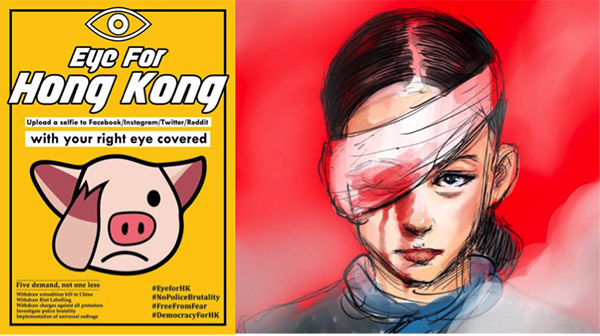

Jingcha Huan Yan 警察還眼 – or, “police: return the eye” – has become a rallying cry of the movement following a police shooting of a young woman in the eye in Tsim Sha Tsui 尖沙嘴. Protesters ritually cover their right eyes or patch them shut with bloodied bandages. Others change their social media profile picture to an artistic rendering of a woman with an eyepatch. Twitter hashtag campaigns such as #Eye4HK have gained international traction, with people all over the world uploading selfies with one eye covered. Through this solidarity, they express support for eyes in Hong Kong – and their visions of a self-determined future – that are currently under curtail.

On the left, an “Eye for Hong Kong” poster with a cartoon pig covering their right eye reading, “Eye for Hong Kong: Upload a selfie to Facebook/Instagram/Twitter/Reddit with your right eye covered. #EyeforHK #NoPoliceBrutality #FreeFromFear #DemocracyForHK.” The yellow poster cites the movement’s five demands, stating “five demands, not one less: Withdraw extradition to China bill. Withdraw Riot Labelling. Withdraw charges against all protesters. Investigate police brutality. Implementation of universal suffrage.” On the right, an artistic rendering of a woman with a bloody eye bandage circulated throughout social media by an unknown artist.

In the months leading up to the protests, the introduction of an extradition bill that would allow residents of Hong Kong to be extradited to the Chinese mainland led to strikes and nearly a quarter of Hong Kong’s citizenry taking to the streets. Carrying umbrellas, the symbol of a 2014 movement in response to China’s mandate that local candidates in Hong Kong elections be preapproved by Beijing, the protesters’ called for Carrie Lam to step down as Chief Executive and for the bill’s immediate withdrawal. While the bill was withdrawn after months of sustained protest, the characterization of the protests as “riots” combined with the excessive use of police force, have led to a set of five demands which now include “universal suffrage”[1] and a systematic investigation into police brutality.

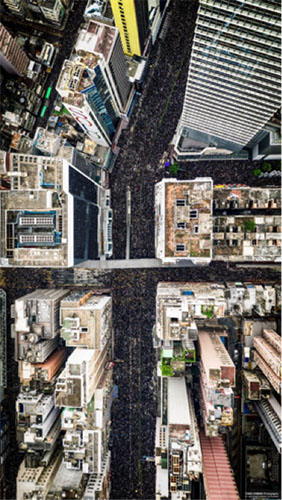

An aerial photograph of hundreds of thousands of demonstrators flooding an intersection in downtown Hong Kong. Photo Credit: 公視新聞網

Videos of police violence have flooded the internet, including one where a police officer tapped an older man on the shoulder, only to spray mace in his face as soon as he turned to see who had tapped him. The notorious Yuen Long Attack—where a mob of over 100 armed men in white shirts intercepted men, women, and children on their way home from the protests, beating and harassing them for over 30 minutes—has confirmed for many Hong Kongers that the police are not on their side. With over a thousand recorded emergency calls, police took an abnormally long time to arrive on the scene, and arrived exactly one minute after the mob left. No arrests were made and the police refused to use the Mass Transit Railway (MTR) security cameras to identify the attackers. For months, rather than engage the voices and concerns that have flooded the streets, Chief Executive Carrie Lam has responded to the protests through a parental analogy, arguing that the protestors, like sons, need discipline. They don’t know what is good for them – you have to discipline them and deny them what they want so that they don’t regret it later.

Caption: On the left, a woman confronts police, pleading: “I’m a mother. You have children here too. Why do you beat them like this? Enough!” Video of this woman’s interaction with the police has gone viral and she has become known as the Hong Kong mother. On the right, a cartoon of the Hong Kong Mother is contrasted with Chief Executive Carrie Lam. The mother’s plea has been contrasted with Carrie Lam’s own presentation of herself as a “caring mother” disciplining her children. Image credits: TEEPR 亮新聞.

As citizens, activists, and democracy protesters invite certain kinds of eyes into Hong Kong through social media and their sharing of stories, an influx of other kinds of eyes has become cause for concern. Over the summer, new smart lamp posts embedded with security cameras have appeared. While Hong Kong’s government has asserted that the cameras are for Hong Kong’s police force and reserved for internal use, within a context of eroding local autonomies in a failing and no longer tenable one-country-two-systems framework, many Hong Kongers question whose purposes and whose future the police force, the government, and its infrastructures serve: Whom do these eyes belong to? How are they being used? And how might they be used in the future? Reports from Xinjiang in Northwestern China detail how surveillance technologies are used preemptively in the brutal suppression and imprisonment of Muslim minorities. Meanwhile, China’s Social Credit System is set to come online in 2020—within which facial recognition technologies will be integrated with video surveillance of social behaviors to produce ‘social credit’ scores that will affect access to services and the ability to travel. While China has insisted that Hong Kong will retain its autonomy and that the Social Credit System will not be implemented there, Beijing’s hand in Hong Kong’s elections, as well as the disappearances of activists and book sellers, leave most Hong Kongers uncomfortable with the way Beijing uses its eyes, hands, and ears in the city. It is within this broader context that Hong Kongers question surveillance systems across scales of sovereignty and political space to fundamentally challenge whose “security” and what kinds of bodily and territorial integrities these systems supposedly serve.

Laser Resistances and Parasolic Evasions

Anthropological studies of surveillance have revealed to us the ways that surveillance processes are simultaneously about seeing and not-seeing. While rendering certain forms and bodies hypervisible, they simultaneously lend to the fading, receding, and disappearance of others (Dubrofsky and Magnet 2015: 17). In worlds where surveillance technologies are more-and-more seamlessly embedded in the governance of everyday life, and where data is increasingly shared between state and non-state entities across local, national, and transnational scales (Glück and Low 2017), the protesters in Hong Kong have something important to teach us about the future of protest and resistance.

Laser pointers and parasols have become symbols of the protest—tangible and physical things that have become a part of what the protests in Hong Kong look and feel like. Yet they are also tools of subversion and resistance on an optical battlefield within which the goal is to be ever-present and seen, but never identified. Cameras, like eyes, work through refraction. Protestors carry green laser pointers, strategically shining them on known camera locations as they move. They also shine them on police, not only to make known the police’s location, but to disrupt potential hidden body cameras.

A city scene with fire and knocked over fencing in the foreground. Green and purple light beams emanate from a crowd in the background. Photo Credit: Deacon Lui, @lsb.co on Instagram

The choice of green laser pointers is far from coincidental. The wavelengths of green light have a wider range. This means they are more visible under a wider range of lighting conditions. Protesters are making use of emissions of highly visible and concentrated light to render themselves hyper-apparent and overly visible —to the extent that they appear to both cameras and eyes as only light, and not as faces or bodies.

Facial recognition technologies are also dependent on what is referred to as light normalization and shadow suppression. Protestors use umbrellas not only to directly shield their faces from cameras and other weapons (like tear gas), but also to wield shadows, moving them in ways unpredictable to light normalization algorithms.

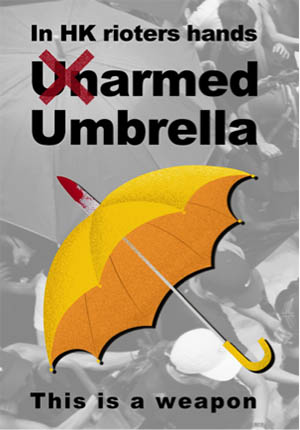

As both the police and (some of) the protestors try to strategically capitalize on mainstream currencies that sympathize with popular notions of “non-violent protest,” Chinese media outlets have launched a concentrated effort to brand these tools as not only weapons, but offensive weapons. Yet in an era of surveillance where governance and policing move increasingly towards preemption, conventional notions of offense and defense—and the ideas of ‘weapons’ and ‘arms’ that rely on them—become murky and untenable. In a time of weaponized mass surveillance, manipulations of light and shadow are part of an arsenal of dissent.

A yellow umbrella with a bloodied knife sticking out of the top. The poster reads, “In HK rioters hands, this is a weapon: Unarmed Umbrella. This image was posted on China Daily’s Twitter account. Comments on the post include a lively debate about what weapons are – including one person who responded with a GIF of tanks in Tiananmen Square, writing “Talking about weapon?”

#BeWater

The 2014 Protests centered around a now familiar protest logic: Occupy. Inspired by global occupy movements, as well as the March 2014 Sunflower Movement’s occupation of the Taiwanese legislature, Umbrella Protesters tried to Occupy Central Hong Kong.

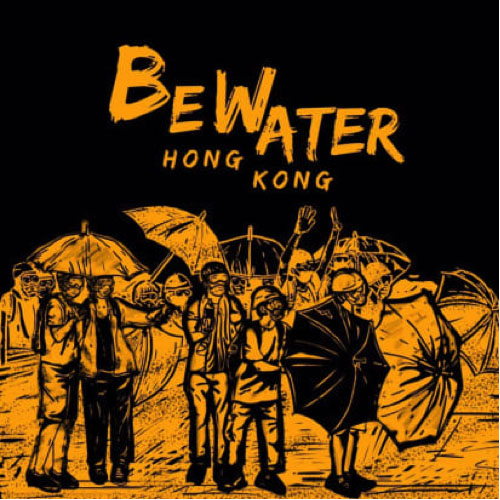

Yet the umbrella revolution has since evolved into what is now being called a revolution of water. #BeWater emphasizes the principles of a new trans-formal approach to resistance. 堅如冰,流如水,聚如露,散如霧 Jian ru bing, Liu ru shui, Ju ru lu, San ru wu : ‘Be strong like ice, flow like water, gather like dew, scatter like mist.’ While the government has arrested student leaders and outspoken activists—with a series of arrests occurring on the anniversary of the 2014 movement—the arrests have had little to no effect on the number of participants in the protests, which are largely organized through Telegram and its real-time polling and communications affordances[2]. The idea of a leaderless protest continues to befuddle Beijing. Water is the new occupy 2.0.

Police officers spray blue-dyed water on protestors. Source: BBC.

To dampen the water-like movements of protesters, the police lace water with blue dye, spraying it through water cannons onto protestors so that they can be identified and later isolated and picked off for arrest should they leave the crowds. Yet citizen-repositories of donated clothing are left in public so that those sprayed can swiftly change clothes.

Supplies move around the city and locations are updated and made known through Telegram, while the polling feature of the app is used to vote on directions and follow through with decisions in real time. Single-fare train tickets are left at stations to confuse the police-accessible tracking systems in metro cards.

A poster circulated through Telegram by an unknown artist. The poster reads “Be Water: Hong Kong.” It shows a group of protestors standing together holding umbrellas.

In Hong Kong, new technologies of surveillance and governance are being met with technologically mediated resistances that rapidly change form and are at times formless. As the eyes of protestors are bloodied, shot, and gassed by conventional weapons, the protestors themselves become water, wielding both shadow and light. Using social media, they send images and videos beyond Hong Kong, inviting eyes in—eyes that might see, or sympathize with what they want to see, not eyes that seek to invade, govern, and colonize. They invite #Eyes4HK.

As new forms of data collection emerge and accelerate and information is managed in ways intended to keep us “in form” — what forms might we assume as we splash and crash against the very bounds of the vessels and technological infrastructures that contain us? In the words of Bruce Lee: “Be Water, my friend.”

On the left, A 2014 protest sign shows a caricature of Bruce Lee and reads “Be Water, my friend.” On the right, another protest sign reads, “Take up your umbrellas” and shows Hong Kongers holding yellow umbrellas. Image credit: VOA news

Citations

Dubrofsky, Rachel E. and Shoshana Amielle Magnet, eds. 2015. Feminist Surveillance Studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Glück, Zoltán and Setha Low. 2017. “A Sociospatial Framework for the Anthropology of Security.” Anthropological Theory 17 (3), 281-296.

[1] In the mid-90s, Hong Kong experienced some democratic reforms during Chris Patten’s term as the last governor of Britain’s administration of the territory. Half of the legislature was allowed to be elected through universal direct vote. The expansion of suffrage slowed down with the 1997 handover to China and the beginning of “one country two systems.” The 31 August decision in 2014 set limits on the 2017 Chief Executive election and the 2016 legislative council. The decision states that the candidates have to “Love the country (China) and Hong Kong” and created an election committee, similar to the U.S. elector college. The protestors are asking for elections through direct popular vote, as well as an open nomination process.

[2] This communications infrastructure was the target of a major cyberattack from inside China in mid-June.

2 Trackbacks