This afternoon, I began to notice increasingly alarming images, posts, and tweets from my interlocutors in Santiago. It appeared that Santiago was on fire, and that the military was in the streets. Images of familiar streets and landmarks now felt doubly familiar, as their similarity to images taken during the coup of 1973 were undeniable. A quick Google search confirmed my fears; Piñera had declared a state of emergency in response to the student metro protests, that there were already deaths, disappearances, and torture reported, and that a curfew had been implemented. Switching over to Whatsapp, I sent frantic messages to my interlocutors and former host family to check that they were safe (they were.) However, it was clear that—even for seasoned activists—this felt different. Many recalled memories or iconic images of the 1973 coup, wondering if history might be about to repeat itself. As the day progressed, I began to receive WhatsApp and Facebook messages with videos, audio recordings, documents, and links with captions like, “save this, they’re trying to erase it.” Though it is unclear to whom this erasing “they” refers, Chileans have clearly learned—at great cost—the importance of actively preserving evidence of political corruption, military and police abuse, and human rights violations.

–Baird Campbell, Field Notes, 10/19/19

Both authors received these kinds of media files with similar messages asking them to save the files. Such statements reveal an anxiety around preserving memory, and indeed around media as a conduit for preservation. To many Chileans, media may be as fragile as memory, just as likely to disappear or be actively erased if not guarded in careful manner. For some, this means circulation outside of the country, away from the grasp of a government who cannot be trusted. Media, then, simultaneously represents fear of erasure as well as a source of hope for engaging world attention. Here we detail the ways that media plays an important role in current Chilean protests, not simply as an organizing tactic (as anthropologists have asserted in global contexts including Black Lives Matter, the Arab Spring, and the Hong Kong Occupy movement), but as a mode of preservation and call to attention on a world screen.

It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years

On Sunday 13 October, Chile’s Transport Ministry announced that the Santiago metro would raise fares by 30 pesos (about 4 cents in USD). With the average Chilean’s monthly salary at $450, in terms of percentage of salary this raised price per metro ticket to the equivalent of the average US worker paying more than $8.50 per ride. In response, students started organizing fare-dodging acts all over the city. Soon the protest spread beyond students, particularly after politicians made poorly calculated comments that workers should wake up earlier for off-peak prices. But these protests are not simply about a fare increase. As many hashtags and memes attest, it is not about 30 pesos, but about 30 years of inequality.

The thirty years to which Chileans refer is the time since Pinochet was voted out of office, ending his dictatorship in 1989. But the story really begins in 1970, when Salvador Allende, a founding member of the Socialist Party of Chile, was elected president of the country. With the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) coalition behind him, he gained victory despite the United States secretly backing candidates who supported their Cold War era ideological opposition to socialism. Shortly after taking office, Allende began implementing socialist reforms igniting US responses including an embargo on food imports designed to foster civil unrest and opposition to Allende, his party, and socialism more generally. When such subversive efforts failed to sway public opinion, the US then backed a military coup d’état by general Augusto Pinochet.

Pinochet is most widely known for his brutal regime which relied on torture and executed or disappeared more than 3,200 Chileans, imprisoned 40,000 and incited over 200,000 to flee the country. But these tactics were designed in service of installing free-market capitalism in the country, and indeed Chile became the test case for economist Milton Friedman’s neoliberal economic theories. The government deregulated business, encouraged importation, cut social services, and privatized resources, social security, education, and healthcare resulting in inflation spiraling to 374% and unemployment growing from 3% to 20%.

These reforms created huge economic disparities in the country, with elites gaining wealth, and more than 45% of the population falling below the poverty line by 1988. While Pinochet’s regime was defeated in a democratic election in 1989, subsequent elected administrations have intensified export-oriented neoliberal reforms, and Chile remains one of the most unequal highly developed countries in the world.

Despite this inequality, Chile’s technological infrastructure has continued to grow, affording most Chileans at least some access to the Internet, whether in their homes, on their phones, or in public spaces like plazas, libraries, and malls. As Eden Medina reminds us, the Allende government (1970-73) experimented with a sort of proto-Internet called CyberSYN, aimed at direct communication with citizens, but the project was abandoned by the Pinochet government. As of 2018, Chile is Latin America’s most Internet-connected country, with an estimated 12 million (70% of the population) 4G users alone. Additionally, over 80% of Chileans have at least one social media account. It is not surprising then that Chileans began to post photos and videos on their social media accounts as public unrest began to grow in October.

We are not at war, we are united

As we watched pictures and videos appear on public social media, as well as appear in our private inboxes, we decided to take an intentional approach to understanding what was happening. On Tuesday, 22 October, we both placed the following request on our Facebook walls, Twitter accounts, and Instagram feeds:

Chilean friends: in light of the situation that you are living through and the desire to do something constructive from afar, we would like to create a bilingual publication that explains the reality that national news networks are not reporting. This will also serve as a register, since we know that much of the content is being erased. We invite all that wish to answer the following question: “What would you like those outside of Chile to know?” We invite you to include images, videos, audio, memes, and other content that shows the reality…We will respect the anonymity of those who participate.

We set up a separate email account to collect the content, and published the address with our request. Over two weeks, only one email was sent to the account, which simply asked “Please confirm for me that you’re receiving videos. Thank you for the help.” We replied in the affirmative, but never received any videos from this (or any other) address.

Instead, friends, former colleagues, and acquaintances began sending videos, audio, and images to both of us directly through Facebook messenger, Whatsapp, and Instagram messages. We also had friends tag us in videos they posted to their public Facebook walls and send links to collective Google Drives filled with protest videos. As a result of the particular choices that Chileans made about public/private and identifiable/anonymous modes of sharing information, we began to take interest in what was being shared as mass posts on Facebook versus what individuals chose to share through direct messages.

Both of us have spent significant time in Santiago, thus the majority of what we received came from people in the metropolitan region. Given time we have also spent in Arica, Iquique, and La Serena, we also received some messages from people in these places. Our account here is based primarily on messages from people in Santiago, but incorporates some from other areas of the country.

We noticed a trend that videos posted on Facebook walls and Instagram feeds tended to have a more positive outlook: they represented peaceful protest and called for unity declaring “we are not at war, we are united.”

Content warning: Below are several examples of independently compiled activist archives, housed on Google Drive. Some of this content is graphic in nature, depicting police and military violence and its aftermath. If you wish to skip this section, please proceed to the next heading “What the Television Doesn’t Show.”

While some of the private messages contained links to widely circulating videos, many videos sent via direct message recorded scenes of violence and destruction. These videos showed burnt out metro stations and cars, angry crowds, and police brutality–such as a protestor being taken into a garden and deliberately shot in the leg, then restrained as he writhes in pain. We both received a video that is visually, simply pointed down at the sidewalk, but the audio records screams attributed to someone being physically tortured in the Baquedano metro station.

What the Television Doesn’t Show

This rift in the types of videos that we received privately, rather than posted publicly indicates a particular understanding of the uses of Internet-based communication. In fact, it seems to indicate an anxiety about digital communication related to its potential ephemerality, a shortcoming that can only be remedied by widespread sharing and archiving across diversified social networks across the globe.

The internet certainly provides a reliable way of communicating to a broad audience, in order to demonstrate what is happening. Yet the nebulous nature of placing something to be seen without a specific recipient/viewer has spurred the tactic of sending media to specific, known individuals.

Media sent to specific individuals such as ourselves seem to act as a kind of memorialization of that which is happening in Chile. In particular, the calls we received to “save this, because it’s being erased” speaks to a project of archiving that no doubt stands in relation to the kinds of documentary erasure that were ever-present during the Pinochet dictatorship. The people that were disappeared, the documents that were destroyed exist as a lacunae, a non-archive of atrocities that overwhelmed the country for years. Viewing current media practices in light of this history, we see anxiety and suspicion surrounding institutional archiving. We may think of these private messages as analogous to the personal memory work in which individual and small groups engaged during and after the dictatorship.

Videos on Facebook walls and Instagram feeds foster a sense of unity and hope, as if to say “We are in this together and we can make a difference.” They show what media aligned with state and elite interests does not, as indicated by the hashtag #LoQueNoMuestraLaTele (What the Television Doesn’t Show). But privately sent videos illustrate a need to preserve information. These are not videos for the pueblo. Other Chileans do not need to be swayed. They are also in the street protesting, or making their grievances known in other ways. Even those Chileans who usually distance themselves from politics are actively taking to the streets and video streams. Much as in 1973, it was not the Chilean people that needed to be convinced. After all, they had elected and supported Allende, despite devastating embargos. Rather, hope lay with attention from outside the country. Thus, the question “What would you like those outside of Chile to know?” invites responses aimed at preserving information understood to be fragile, likely to disappear, in danger of erasure, and important for inciting outside support.

“The Largest Protest in Chilean History”

After a week of some of the most constant and violent protests in recent memory, spanning the entire length of the country, on Friday, 25 October, more than 1 million Chileans gathered in Plaza Italia—the traditional starting point of Chilean protests—for what quickly became known as “the largest protest in the history of Chile.” Circulating images showed a crowd that occupied the entire plaza, the surrounding streets, and even continued across the Mapocho river which cuts through the city. The size of the protest has been key to the ongoing framing of the movement, #ChileDespertó or #ChileWokeUp. The presence of more than a million protestors in one location—in a country with a population of just over 17 million—lends credence to the idea that Chile, and not just a small group of troublemakers, has truly awoken.

Additionally, social media played a crucial role in this framing, troubling the physical limitations of Plaza Italia, allowing those who were not physically present to experience the feeling of “being there,” as well as to project the idea of a united front of Chileans, both in and outside of the capital, who were bearing witness and participating in this seemingly unprecedented show of citizen outrage and solidarity. This feeling of connection between physical and virtual populations contributed to the growth of simultaneous marches throughout the provinces, preventing the Piñera government from continuing to claim that protests were in any way isolated incidents that would be quickly mollified by repealing the controversial metro fare hike. Saturday’s protest made clear that activists would not be satisfied with tokenistic gestures of capitulation to the protest’s demands, but rather that they would only be satisfied by deep structural changes.

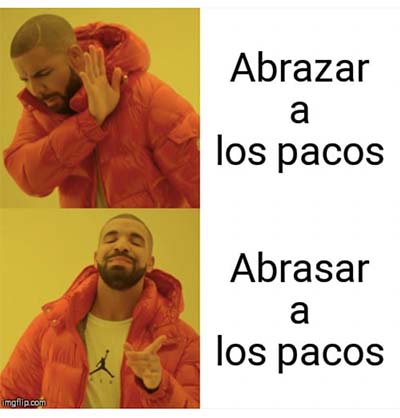

Don’t hug the police!

Top: “hugging the cops.” Bottom: “burning the cops.”

At the same time that videos have been shared of police and military suppressing protest in violent and arguably illegal ways, many Chileans have used social media to expose the role of undercover officers in setting fires, vandalizing property, and encouraging looting—actions the Piñera government had persisted in blaming on the largely peaceful protesters. But Piñera has been forced to reckon with the fact that these tactics are not as reliable as they once were. Having failed to convince the general public with tactics cribbed directly from Pinochet’s playbook—blocking the arrival of basic goods to supermarkets, setting fire to the most crucial metro stations of the city, and attributing the climate of civil unrest to the wave of Venezuelan (and therefore supposedly communist) immigrants who have made Chile their home in the last few years—the police and armed forces began to take a different tack.

Over the weekend, images began to emerge of officers putting down their weapons, hugging protestors, and engaging in behaviors that might blur the line between the two sides of the struggle. Just as quickly as this began, online activists launched an aggressive campaign discouraging the public from being fooled by these photo ops, and suggesting that the Piñera government was intentionally pushing these images in an effort to give both Chileans and the outside world the impression that things had “returned to normal.” The state of exception was revoked Monday 28 October, effectively removing the military from the streets, and Piñera replaced a significant portion of his cabinet. Nonetheless, Chileans have remained overwhelmingly steadfast in their refusal to accept what they view as distractions from the structural issues of corruption and abuse at the center of the public outrage. As of the writing of this piece, protests continue daily throughout the country, with themes such as pension reform, minimum wage increases, and a Constitutional plebiscite aimed at finally replacing the current Constitution, which was written under Pinochet. Chile is the only country in the world to preserve a Constitution written by a dictator, and activists have long called for the government to write this wrong, a demand that has fallen on deaf ears until the beginning of the latest wave of protests.

Conclusion

As we continue to receive videos and watch official Chilean news reports about the ongoing crisis, we are struck by the importance placed by both sides on the ability to control media messages. Just as Pinochet’s economists attempted to use television programs like “Free to choose” to gain public consent for their policy, the media is a battleground in Piñera’s attempts to gain international legitimacy. His discourse travels around the world through mass media outlets while average Chileans connect directly with friends and acquaintances. They activate diversified social networks across the globe to preserve evidence of abuse. As we were preparing to publish this piece, a national strike on November 12 reactivated these networks, and we anxiously watched for news of the President’s next move.

Chileans know the last 50 years of their country’s history well. “Ni perdón, ni olvido” (Neither forgive nor forget) remains an important mantra about the Pinochet dictatorship. Yet memory is fragile and can be corrupted. With this in mind, social media offers an alternative form of memory, (hopefully) less vulnerable to obliteration, and certainly a mode through which el pueblo can have an active hand in constructing the narrative.

References

Bonilla, Yarimar and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. #Ferguson: Digital Protest, Hashtag Ethnography, and the Racial Politics of Social Media in the United States. American Ethnologist 42(1):4-17/

Collier, Simon and William F. Sater. 1996. A History of Chile, 1808-2002. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Fu, KW, and CH Chan. 2015. Networked Collective Action in the 2014 Hong Kong Occupy Movement: Analysing a Facebook sharing network. The 2nd International Conference on Public Policy (ICPP 2015), Milan, Italy, 1-3 July 2015. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.851.4400&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2012. Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism. New York: Pluto Press.

InvestChile Blog. 2018. Chile: Latin American Leader on Digital Connectivity. (13 July) http://blog.investchile.gob.cl/chile-latin-american-leader-on-digital-connectivity

Klein, Naomi. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, NY: Picador.

Medina, Eden. 2011. Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Poblete, Jorge. 2019. Chile lifts curfew a day after massive protests. LA Times (26 October). https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2019-10-26/chile-lifts-curfew-a-day-after-massive-protests

Sherwood, Dave, and Natalia A. Ramos Miranda. 2019. One million Chileans march in Santiago, city grinds to a halt. Reuters (25 October). https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chile-protests/one-million-chileans-march-in-santiago-city-grinds-to-halt-idUSKBN1X4225

United Nations Development Program. 2017. Unequal: Origins, Changes, and Challenges in Chile’s Social Divide. New York: United Nations. chrome-extension://oemmndcbldboiebfnladdacbdfmadadm/https://www.undp.org/content/dam/chile/docs/PNUD_en_la_prensa/2017/undp_cl_pnudprensa_sep-Progreso.pdf