Image posted by Selahaddin Abi on Facebook

“Every week somebody comes here to take photos of our laundry and put it up on the internet. Today, I took one and put it up right here. It’s not our laundry, but it’s a bear. This might be a dump, but this is my dump, and I care about what goes on the internet about it.”

Thus wrote Selahaddin Abi in his description of the photograph he posted on Facebook. It was a bear suit captured with his phone when he was roaming the streets of Tarlabaşı, as he has done almost every day for the past twenty years. For anyone who lives in the United States and made a trip to Target or Walmart, one of these suits—often produced for children, or those who simply want to be comfy through, say, harsh winters of the Midwest—is not a singular sight. Yet for someone living in Turkey, where large chain stores do not necessarily hold them, they are less commonplace, if not amusing. And, when photographs of Tarlabaşı are concerned, it is a deviation from depictions of colorful clothes, undergarments, towels hanging from clotheslines that seem to bind two buildings to one another, that seem to fascinate affluent people of Turkey or tourists from elsewhere, that become the object of an overwhelming majority of photographs of this neighborhood.

When you type in Tarlabaşı into Google Image Search or Instagram, variations of images below are very likely what you’ll encounter. Home to Istanbul’s Jewish, Greek, and Armenian minorities (among others) throughout decades preceding 1960s, when non-Muslim minorities were pushed out of the country, many buildings, adorned with art nouveau architectural elements, in the neighborhood were left vacant. Soon, these buildings were filled with Turkish migrants from Anatolia coming to the city to find jobs, internally displaced Kurdish people following Turkey’s attacks on the Kurdish armed forces in the 1990s, Roma minorities, transsexual communities that needed affordable dwellings, and more recently, newcomers from across the Middle East, West Africa, and post-Soviet Central Asia. Throughout, the imagination of the neighborhood morphed into a dark reputational geography (Parker and Karner 2010) persisting until this day. The underground drug and sex economies of Istanbul, among other forms of illicit activities, were associated with Tarlabaşı, combined with associations of poverty and desolation.

Google Image search of Tarlabaşı done on January 2020

In 2006, these images became more severe following the announcement of the ruling Justice and Development Party’s urban transformation project law. Accordingly, neighborhoods deemed “derelict and delinquent” could be put up for development projects (Kuyucu and Ünsal 2010). The former residents would be compensated with an (unfair and unjust) amount of compensation determined by the government. In Tarlabaşı, for instance, the construction of a luxury residential and business complex would follow, called Taksim 360. The project swallowed a portion of the neighborhood, displacing its residents, who are still contesting the unfair compensations they received (particularly vis-a-vis the astronomical sums for which Taksim 360 properties are sold) in courts. And these struggles led to even more researchers, artists, photographers, journalists and the like to populate the neighborhood in search of stories and images showing “the tragedy of humanity” and “the lives that have been ruined” in the neighborhood (Alkaç 2017; Gürçay 2017). Clotheslines, rubbish on the streets, children looking down windows were perennial images accompanying these stories, so much so that throughout this period, Tarlabaşı became the second most Instagrammed part of the city, following the touristic Sultanahmet/Eminonu. Poverty porn in an architecturally rich setting was appealing, both for research/journalism/art careers and for social status often forged through social media.

Resource: www.yeniemlak.com

Resource: www.yeniemlak.com

While Tarlabaşı has often been overdetermined by those who take it upon themselves and assume their right to represent the neighborhood, Tarlabaşı residents remain intimately cognizant and incisively critical of their representations on social media. “Sometimes they [referring to people with professional cameras or iPhones] come in, asking for even specific poses, like holding my one year old out the window, so that they can have an exciting picture, or so that they can say whatever they want to say about us–say we are poor, uneducated, or dangerous! When we say, come in, let’s have tea, let’s chat, if you want to learn about this place, they pack up and leave. This is not a photography studio. This is our lives. Why would I hold my child over the window?!” said Ayşe Abla, Selahaddin Abi’s wife. “They look for sad, ‘no hope’ stories. This is not how we see ourselves, nor is it how we want to be represented on the internet or on Facebook or whatever!”

And so, she and her husband take it to social media. They would often post photographs they took of parts of daily life they deemed were interesting and important for their lives, those that show the resilience of people in Tarlabaşı in the meantime of urban transformation, those that illustrate how they are engaged in future-making throughout delayed processes of urban transformation. From time to time, they’d capture photographers seeking to represent them without engagement, and post them with captions such as “another person on a photo safari.”

A photograph from Selahaddin Abi’s Facebook page, capturing a “photo safari” instance

A photograph Ayşe Abla took during a drawing session led by an artist, Tamara Becerra Valdez, engaged in solidarity work in Tarlabaşı.

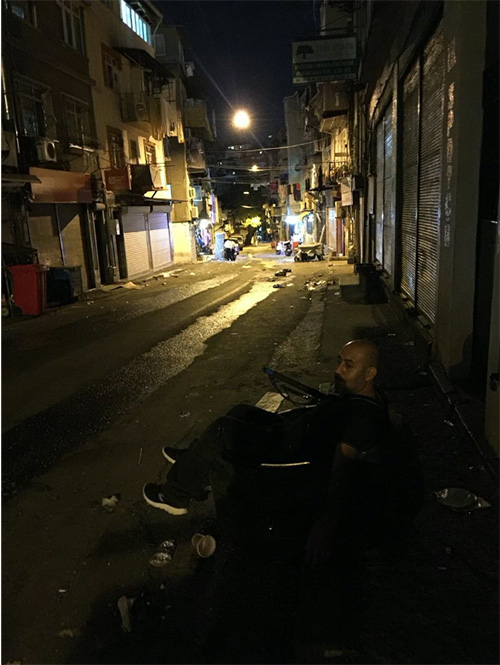

Ayşe Abla had a proclivity to take pictures of children doing productive activities–such as drawing or being tutored–on the street with young people she met, young people engaged in solidarity work with residents. Selahaddin Abi often was interested in objects that in ways subverted popular images of Tarlabaşı, like the bear costume on clotheslines. He also enjoyed engaging with these objects that made up the textures of the neighborhood, amplifying his statement that “it is [his] dump”: a popular saying in Turkish indicating one’s belonging to a place or a community, but one that also turned the popular representations of Tarlabaşı on their heads. For example, when we were taking a stroll around 3 am towards the weekly Dolapdere Flea Market, which is set up at midnight on Saturday until the end of the day on Sunday in the neighborhood adjacent to Tarlabaşı, he saw a huge tire in the middle of the street. He sat in the tire itself, giving me specific directions on angles as I took his photos. Later that night/morning, he posted the pictures with the captions: “Anything lies on our streets. Some think its garbage, I think not. They’re our streets, even with tires left on their sides. Some think it’s a dump, I know it’s not. I can take a seat in this tire, my kid can come the next day and play with his friends. We value our streets, we know what things in them mean!”

Selahaddin Abi in the aforementioned tire, from his Facebook page

John Jackson (2013), in his eloquent critique of Geertzian thick description, points out the hubris this kind of engagement can generate in fieldwork, particularly since making thick descriptions implies an a priori authority to represent. He shows that communities often are adept auto-ethnographers who represent themselves through various media practices, and invites ethnographers to value such “thin descriptions.” In Tarlabaşı, social media emerges as a medium through which residents challenge the boundaries of description itself. Social media can serve to turn places into objects of representation. But it also affords opportunities for overrepresented communities to seize the means of representation. Rather than thinking through the thick and thin of description, I consider social media as a productive terrain through which communities represent themselves, on the one hand, and convey their important critiques of representational practices in academia, journalism, or other venues, on the other. Fatma Abla and Selahaddin Abi used their Facebook and Instagram accounts to do precisely that. Of course, critiques and practices of representation well precede social media. Yet, in the current landscape of urban life, such everyday technologies embody both the production and subversion of overrepresentation, particularly when dark reputational geographies are concerned. Creative Facebook posts of those like Selahaddin Abi or Ayşe Abla present a lot to learn from for ethnographers.

References Cited

Alkaç, Fırat. 2017. “Dokunsan çökecek hayatlar.” Hürriyet, July 12, sec. Gündem. http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/dokunsan-cokecek-hayatlar-40548466.

Gürçay, Ercüment. 2017. “Arafta kalmış bir tükeniş hikâyesiydi Tarlabaşı.” Yeşil Gazete, March 11, sec. Haftasonu. https://yesilgazete.org/blog/2017/03/11/arafta-kalmis-bir-tukenis-hikayesiydi-tarlabasi/.

Jackson, John L. 2013. Thin Description: Ethnography and African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kuyucu, Tuna, and Özlem Ünsal. 2010. “‘Urban Transformation’ as State-Led Property Transfer: An Analysis of Two Cases of Urban Renewal in Istanbul.” Urban Studies 47 (7): 1479–99.

Parker, David, and Christian Karner. 2010. “Reputational Geographies and Urban Social Cohesion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (8): 1451–70.

1 Trackback