In 2000, a United Nations Resolution designated June 20th World Refugee Day. In the week leading up to this day, countries throughout the world pay homage to the ideals of the refugee rights movement through public festivals celebrating their migrant communities’ cultures, social media campaigns on refugee resilience, and declarations of their commitment to protect those seeking asylum. Historically, nation-states have employed such public messages to emphasize their identities as benevolent, humanitarian actors. However, what these proclamations elide is not only the violent ways that individual nations reject asylum seekers[1], but the collective ways that countries work together to inhibit their mobilities. Both the technologies of detection and deterrence as well as anti-refugee rhetoric, while based on insular ideas of nationhood and ‘who belongs,’ are also increasingly dependent on collaborations and partnerships with other nation-states. In attempts to control refugee movement, multiple nation states are both entangled and willingly involved in a global effort to contain, reroute, and eventually immobilize asylum seekers from the global South seeking protection in liberal democratic states. While there has always been an international refugee regime since the inception of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, it is worth paying attention to the new ways in which nation states are learning from and relying upon each other to govern where refugees can and cannot go.

Tweet from Norway’s Directorate of Immigration on Nov. 2, 2015 about the consequences Afghan asylum seekers face upon reaching Norway.

As an anthropologist who studies the Australian state’s relationship to migrants from the Middle East and South Asia, I have recently turned attention to how attitudes and technologies of border control are detached from the territorial boundaries of contiguous mainland Australia itself. What I hope to outline in this piece is the extent to which congruent attitudes and technologies around detection and deterrence are appearing throughout the so-called West. Many scholars have written about how the state weaponizes and manipulates different terrain to deter migrant movement through prolonged suffering and death (De León 2015, Donato et al 1992, Weber and McCulloch 2018). In the US, increased physical barriers and policing in high traffic areas of the US-Mexico border has forced migrants to take alternative and dangerous paths through desert terrain. In Australia, the excision of the mainland from its ‘migration zone’—the only area where migrants could claim asylum from the Australian state—effectively rerouted asylum seekers to ‘excised offshore places’ such as Christmas Island, and the Cocos islands among others. In this piece, I offer a preliminary look at the global resonances of these approaches because the control of migrant bodies requires us to look beyond the violence at the territorial border. Doing so could enable an understanding of how refugees are constructed and dealt with as ‘inconvenient figures’ (Aleinikoff and Zamore 2020) through interconnected border control regimes. Moreover, it is through these interconnected strategies that nation-states reinstantiate national sovereignty while simultaneously generating a sense of “Western” identity that is premised on how effectively they keep those from the global South out.

Australia’s Influential Approach to Border Control

In recent years, the Australian state has developed a range of technologies designed to detect and intercept asylum seekers who attempt to reach Australia’s mainland via maritime routes. This includes taking an unprecedented militarization of its maritime borders, which span the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Through policies such Operation Sovereign Borders (2013) and Operation Reflex (2017), Australia’s Maritime Border Command (MBC) has drastically expanded its surveillance and interception technologies and taken them further offshore. Additionally, in 2018, the Department of Home Affairs created the ‘future maritime surveillance capacity’ project.’ This project seeks to ‘provide the next generation maritime surveillance capability to counter current and emerging civil maritime threats to Australia … [and] provide surveillance capabilities that enable timely and effective deterrence, prevention and response operations to protect Australia’s borders and exercise sovereign rights’. Over the past ten years, maritime surveillance technologies have expanded to include small cube satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles, artificial intelligence, and swarm technology to detect and intercept suspicious vessels (Australian Strategy Policy Institute, 2018).

These maritime surveillance technologies in Australia’s exclusive economic zone—the area of coastal water and seabed within 200 nautical miles of Australia’s coastline—were part of what the Home Affairs Department called the creation of a ‘ring of steel.’ This metaphor was used to describe the nexus of military personnel and technologies surrounding the border that makes ‘unauthorized maritime arrivals’ and other so-called criminals such as ‘human smugglers’ subject to similar detection and interception strategies. Through a combination of oceanic apparatuses, unmanned surveillance technologies, and Australian Defense Force vessels, Australia has treated maritime arrivals, who historically, have fled political turmoil, ethnic persecution, and war in the Middle East and South Asia, as vectors of threat to national security. Its blatantly exclusionary approach to border control has served as inspiration to other world leaders.

In September 2019, former Prime Minister Tony Abbott visited the Third Budapest Demographic Summit in Hungary, and shared numerous strategies with EU leaders about the Australian model for deterring migrants in a lecture titled “Immigration: What Europe can learn from Australia.” He pointed specifically to the success of Operation Sovereign Borders which extended previously terminated policies of rerouted asylum seekers to offshore islands for processing and unequivocally refused to resettle any asylum seeker on Australian territory. Abbott pointed to the effectiveness of Hungary’s similarly hardline approach under notoriously xenophobic leader Viktor Orbán, which includes detaining asylum seekers in container camps at the Hungarian-Serbian border, and erecting huge razor-wire fences along its borders.

U.S. leaders have also been inspired by Australia’s ‘thorough’ approach to border control. In 2018, Washington-based Assistant Chief Patrick Stewart, Branch Chief of the Geospatial Information Systems program for US Border Patrol and lead for US Customs and Border Protection addressed the Australian Security Summit on how both countries could benefit from new geospatial information systems in order to better detect “unlawful arrivals,” In his lecture, Stewart expressed how impressed he was that “Australia had managed to create the Department of Home Affairs [a ‘super ministry’ formed in 2017 that combines the military, immigration and border protection, and customs, much like the Department of Homeland Security in the US].” He ended by speaking about the potential for both countries to transfer operational and strategic knowledge.

Regional Collaborations in Deterrence

The idea of treating border control as a regional problem and responsibility is also a key characteristic of Australian approaches and has been adopted by other nation-states. As a border security operation, OSB relied on collaborations with multiple surrounding countries to detect boat arrivals with the express purpose of rerouting them away from Australian mainland territory. With a budget of AUD$420 million (US$387 million in 2013), the Regional Deterrence Framework worked with regional transit hubs for asylum seekers such as Indonesia to prevent asylum seeker vessels leaving for Australia. Part of the RDF entailed the Australian government buying back Indonesian boats from ‘people smugglers,’ and would provide monetary and technological support to wardens of local communities. These wardens would then provide intel to the Australian government from the Indonesian National Police on ‘people smuggling’ operations.

The EU has also partnered with nearby countries to deter and reroute asylum seekers from the Middle East, through the idea of ‘cooperative deterrence’ (Hathaway and Gammeltoft-Hansen 2015). This approach entails contracting out private border agencies to work with Turkey, Libya, and other African countries around intelligence gathering, surveillance, and maritime anti-smuggling, (Albahari 2018, 123). Additionally, since 2015, 22 EU states have been collaborating with each other in a project called EUNAVFOR Med Operation Sophia, which utilizes ships, aerial vehicles, and submarines, as well as maritime patrol aircrafts and drones throughout the Libyan coast (2018, 124) to detect maritime arrivals.

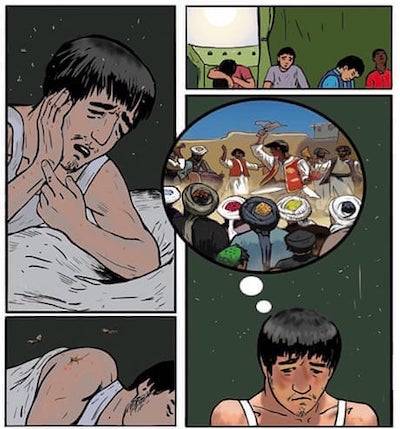

Images from a graphic campaign circulated by the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection throughout Afghanistan detailing what would happen to asylum seekers if they attempted to come to Australia.

Shared approaches to migrant deterrence also center around public media campaigns. Since 2013, the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection has been circulating pamphlets and billboards in Arabic, Dari, Persian, and Indonesian throughout the Middle East, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Indonesia, telling asylum seekers that they will never be able to resettle in Australia, and that if they did make the journey, they would be faced with horrible living conditions and prolonged depression and anxiety due to their imprisonment and no chance of a life in Australia. Reminding migrants of the slow death that was to come was a key way that billboards approached deterrence. Other media campaigns have recently been adopted by European countries like Austria, which in 2016 commenced an ad campaign with billboards in Afghanistan’s five biggest cities and on over 1,000 websites that say “No asylum in Austria.” Scandinavian countries like Denmark and Norway have circulated similar ad campaigns, in Lebanon and Afghanistan respectively. In 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump tweeted, “These flyers depict Australia’s policy on Illegal Immigration. Much can be learned!” before a meeting with current Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison at the G20 summit in Japan.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-mnS3YxD1Y

Outsourcing the Work of ‘Processing’

When migrants cannot be deterred from taking a perilous journey, the Australian state has rerouted them to offshore processing centers, a technique certain EU countries have also implemented. Although the use of offshore detention centers began in Australia in 2001, it was in July 2013 under the administration of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd that the Pacific Solution was given a new iteration. Known as the PNG (Papua New Guinea) Solution, it was agreed that asylum seekers who arrive in Australia via boat without a visa would never be given residency or resettled in Australia, and would instead be diverted to Manus Island. In effect, the administration outsourced the work of processing asylum seeker claims by putting them under the jurisdiction of another state. From 2012 to 2018, approximately 2000 people were imprisoned in detention centers in Manus and Nauru, most of whom were only recently resettled through third party agreements with the US (about 20 people remain in Papua New Guinea’s Bomana immigration detention center in inhumane living conditions with few updates on their future resettlement, while about 32 people agreed to return to their countries of origin after years of being imprisoned).

The outsourcing of detention work has also appeared in the EU in recent years, in an attempt to both control migrant mobilities through prolonged displacement, while absolving itself of legal responsibilities around migrant welfare. According to a 2019 Human Rights Watch report, certain EU states, such as Italy, are providing support to the Libyan Coast Guard to intercept migrants at sea, after which they are taken back to Libya for arbitrary detention, where they face degrading conditions and the risk of torture, sexual violence, extortion, and forced labor.

A Global Perspective on Governing Refugee Mobilities

As asylum seekers confront the state’s rerouting, containment, and immobilizing strategies, nation-states reinstantiate their physical borders as tightly sealed barriers. However, by taking a global perspective, we can see that the exclusionary force of the border makes itself known in more spatially diffuse ways through multiple international actors, agents, and apparatuses. The siphoning off of the border, then, is actually increasingly dependent on an extractive relationship with other countries to do the ‘dirty work.’ In Australia, some scholars have described the state’s offshore detention regime in Manus and Nauru as akin to a neocolonial archipelago (El-Enany and Keenan 2019, Grewcock 2014, Mountz 2011, Teaiwa 2015) due to the extent to which it exploits foreign economies and environments in order to sustain itself. This begs the question of how the externalization of border control replays and reenacts colonialism’s extractive and exploitative modes through governing the bodies and mobilities of asylum seekers? If a key component of sovereignty centers around claiming a monopoly on the legitimate means of movement (Torpey 1998), then what types of extractive relationships does sovereignty rely on when multiple resource-poor countries are brought into the work of controlling human movement?

In recent years, the co-emergence of shared approaches in border management across Europe, Australia, and North America, have also signaled the development of a “Wall around the West” (Snyder 2000) or the “West as a Gated Community” (Tholen 2010, 261). To what extent does a shared interest in the deterrence of asylum seekers serve as a newly salient anchor for a global Western and liberal identity? What do strategies of deterrence reveal about new configurations of national sovereignty, global identity, and the very material ways that migrant life and death are managed across geographies?

In a time of uprising against systemic racism in the US and globally, attending to globally congruent strategies of deterrence is key to understanding the nature of racialized border control practices today. In Australia, Refugee Week includes an impressive lineup of film festivals and conferences that bring together refugee policy advocates and social service organizations. However, Australia’s stated commitment to welcoming refugees belies a more nefarious set of policies, attitudes, and apparatuses that are regrettably shared amongst numerous nation states and that enact the antithesis of Refugee Week itself—turning particular groups of migrants away and in some cases, facilitating their death, through a globally interconnected regime of violence.

[1] I use ‘asylum seeker’ throughout the paper to connote those who have not yet been recognized as ‘legitimate refugees’ either by the UNHCR or by the states in which they seek protection and by extension, the status of ‘genuine refugees.’ I also use ‘refugees’ because in my view, asylum seekers do have legitimate claims to refugee status even though institutions tasked with officially determining their claims do not always offer that political recognition. While recognizing that not all migrants are asylum seekers, I also use the term ‘migrant’ in order to emphasize asylum seeker identities as human beings who are in movement, and who are also being immobilized in a variety of ways.

References

Albahari, Maurizio. 2018. “From Right to Permission: Asylum, Mediterranean Migrations, and Europe’s War on Smuggling.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 6(2): 121-130.

Aleinikoff, Alexander and Leah Zamore. 2020. The Arc of Protection: Reforming the International Refugee Regime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

“Australia’s hard line on asylum gets Donald Trump’s approval.” The Financial Times. 8 July 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/8fef57ba-9c7d-11e9-9c06-a4640c9feebb.

Bos, Stefan J. “Tony Abbott has some controversial ideas on migration and he thinks Europe should take them on.” ABC News. 4 September 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-05/tony-abbott-wants-europe-to-take-on-his-migration-ideas/11480758.

Coyne, John. “Australia’s future maritime surveillance capability: It’s not just about technology.” Australian Strategic Policy Institute. 27 March 2019, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australias-future-maritime-surveillance-capability-its-not-just-about-technology/.

De León, Jason. 2015. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Donato, Katherine M., Jorge Durand, and Douglas S. Massey. 1992. “Stemming the Tide? Assessing the Deterrent Effects of the Immigration Reform and Control Act.” Demography 29(2): 139-157.

El-Enany, Nadine and Sarah Keenan. 2019. “From Pacific to traffic islands: Challenging Australia’s colonial use of the ocean through creative protest.” Acta Academica 51(1): 28-52.

Grewcock, Michael. 2014. “Australian border policing: regional ‘solutions’ and necolonialsm.” Institute of Race Relations 55(3): 71-76.

Hathaway, James C, and Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen. 2015. “Non-Refoulement in a World of Cooperative Deterrence.” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 53(2):235–284.

Keane, Bernard. “Military reshuffle: Abbott’s ‘Operation Sovereign Borders.’ ” Crikey. 25 July 2013, https://www.crikey.com.au/2013/07/25/military-reshuffle-abbotts-operation-sovereign-borders/.

Kuper, Stephen. “Technology is changing the face of border security: US Border Protection Chief.” Defence Connect. 23 July 2018, https://www.defenceconnect.com.au/intel-cyber/2609-technology-is-changing-the-face-of-border-security-us-border-protection-chief.

Mountz, Alison. 2011. “The enforcement archipelago: Detention, haunting, and asylum on islands.” Political Geography 30(3): 118-128.

Nasralla, Shadia. “Austria plans ad campaign to deter Afghans from seeking asylum.” Reuters. 1 March 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-austria-afghanistan/austria-plans-ad-campaign-to-deter-afghans-from-seeking-asylum-idUSKCN0W34XQ.

“No Escape from Hell: EU Policies Contribute to Abuse of Migrants in Libya.” Human Rights Watch. 21 January 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/01/21/no-escape-hell/eu-policies-contribute-abuse-migrants-libya.

“Norway launches anti-refugee advertising campaign.” The Telegraph. 4 November 2015, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/norway/11975535/Norway-launches-anti-refugee-advertising-campaign.html.

Taylor, Josh. “Last asylum seekers held in Papua New Guinea detention centre released.” The Guardian. 23 January 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jan/24/last-asylum-seekers-held-in-papua-new-guinea-detention-centre-released.

Teaiwa, Katerina. 2015. “Ruining Pacific Islands: Australia’s Phosphate Imperialism.” Pacific Forum 46(3): 374-391.

Tholen, Berry. 2010. “The changing border: developments and risks in border control movements in Western countries.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 76(2): 259-278.

Torpey, John. 1998. “Coming and Going: On the State Monopolization of the Legitimate ‘Means of Movement.’” Sociological Theory 16(3): 239-259.

Weber, Leanne and Jude McCulloch. 2018. “Penal power and border control: Which thesis? Sovereignty, governmentality, or the pre-emptive state?” Punishment & Society 0(0): 1-19.