What is commonly known as the Colombian conflict refers to more than six decades of enduring violence. During these years, a number of peace agreements have been signed with some of the main actors, including the agreement signed with paramilitaries in 2005[1] and the recently signed peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—the FARC guerrilla group[2]. Attempts to build peace have included compensation and reparation to victims. In this process, the forensic identification of bodies has been crucial, placing forensic experts center-stage.

The forms of violence of the conflict have been many, with ever-changing forms of killing, torturing, and disappearing people being practiced in Colombia. Political parties, drug traffickers and capos, political guerrillas, paramilitary forces, the state and the army, serial killers and common criminals have all committed open acts of violence in the form of attacks on civilian populations and violence to destabilize political opponents. Additionally, the armed conflict has not been limited to one single area of the country. Instead, its shape-shifting nature has produced a geography of violence that extends across the country, affecting both rural and urban populations. Similarly, those considered direct victims have changed over time and have swollen in number. According to the National Registrar of Victims, there were 1,745,628 registered victims of forced disappearance, homicide, murder or whose bodies are yet unidentified as of March 1, 2018[3]. In such a context, the role of forensic experts is crucial. However, forensic specialists’ knowledge circulation is very much restricted to juridical-legal settings. What is asked of them are principally death quantifications and measurements such as bone dimensions and DNA samples, along with the forensic archaeological context—objects found in graves (clothes, robes, documents, etc.) and the disposition of the body. However, the knowledge these specialists have and produce—I argue—is much richer, and more valuable, than that.

Why ask anything (else) of forensic anthropologists?

I became interested in forensic anthropologists’ knowledge and practices involved in identifying victims in violent contexts while doing research on a particular portion of the Colombian armed conflict (see Olarte-Sierra et al. 2014). My interest is not on what is asked of them in juridical-legal contexts, that is, the above-mentioned quantifications of death and violence. Instead, I focus on forensic anthropologists’ qualitative knowledge, which I consider of paramount relevance because forensic specialists—especially forensic anthropologists and archaeologists—are uniquely positioned to make sense of the violent past and present. This, I found, is the case for at least three reasons:

- Their responsibility is to identify all victims of a conflict, to help determine (and convict) perpetrators, and to establish the conditions and forms in which violence took place;

- As investigation is central to their work, they must have deep and thorough knowledge of the socio-political, cultural, and historical dynamics of the case;

- Forensic specialists must develop contextual and multiple working scenarios to produce knowledge about the nature of violence in order to make sense of the marks it leaves on bodies and landscapes.

In this context, I have been studying forensic anthropologists’ qualitative knowledge of the Colombian conflict with the purpose of providing new elements to nuance and enrich our understandings of it.

Logging practices as technologies of memory

Some of the many field diaries kept by one of the forensic anthropologists of the Prosecution Office in Bogota. Photo: María Fernanda Olarte-Sierra

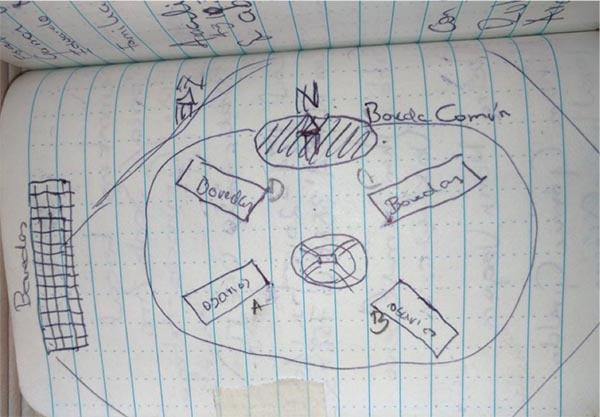

While approaching forensic specialists’ qualitative knowledge, one element that has stood as central are their field diaries and various registration practices that involve writing, sketching, and drawing. It is usual to see entries with different hand-writing styles as forensic anthropologists dictate to their assistants or other team members what they are seeing while digging up the graves. However, when not digging, forensic anthropologists fill in their diaries on their own. In doing so, forensic anthropologists document their processes with various objectives. On the one hand, they must keep track of their tasks, activities, and findings in order to fill in official and standardized forms and formats that become part of the criminal investigation of each case—after all, the diaries themselves may become evidence of a specific case. On the other hand, they keep logs with very detailed information that also serve the purpose of registering what goes on in the field, such as weather and socio-political conditions of the site, phone numbers of team members of the exhumation diligence, personal information of different informants, and all the details of the grave they dig (number, position and state of bodies, and other related elements as cloths, robs, accessories and so on). Additionally, forensic anthropologists register in their field diaries what goes on in their minds, charting the connections and inferences they make. In that sense, such diaries also serve as triggers of a reflexive process of forensic anthropologists’ own work, a practice they share with most social and cultural anthropologists. “We never cease to be anthropologists and our field diaries are part of our daily practice”, said Esteban, a humanitarian forensic anthropologist whom I had the opportunity to interview.

These logs are for forensic anthropologists’ own processes of thinking and working on each case, and they only leave the direct control of these investigators when they are to be used as evidence in an investigation. However, one of the most important aspects of such logs and logging practices is that, given their meticulousness, when taken together, these diaries become a detailed testimony of the changing dynamics of violence throughout the many decades of conflict. These “technologies of memory” (Bowker, 2008) serve a dual purpose: to help the forensic anthropologist understand and incorporate information that is not made available to the general public, but also to provide information to others about how different actors establish their enemies and treat the enemy’s body. Similarly, with such registration practices, one can take a look at how different population groups have become targets, how the violence has moved across the country, how armed actors have changed and, with them, how new killing and burying practices have appeared. While diaries are a repository of these dynamic characteristics of violence, they also constitute a tool for forensic anthropologists themselves to attune their practices to the ever-changing context and forms in which death has happened.

So, why and what to ask?

Forensic anthropologists’ experiences and qualitative knowledge provide context and content to the different forms of violence that have been perpetrated in multiple scenarios within and beyond Colombia. One way to access such knowledge is through their logging practices. As expressed before, these technologies of memory have the potential to constitute an open window to particular dynamics of the conflict and, thus, if taken together, they have the potential to become a multi-vocal memory of the conflict. In this sense, such technologies of memory can sharpen and make more complex our understandings of the conflict.

Allow me an example here. It was through the comparison of the notes and experiences of different forensic anthropologists across the country that Colombia’s Prosecution Office could establish a pattern of killing and burying practices of the paramilitary group known as AUC (United Self-Defenders of Colombia). By taking into account forensic anthropologists’ diaries, knowledge and experiences, around the year 2007 the Prosecution Office was capable of acknowledging the extent to which the AUC was a franchise of terror, and that their doings were beyond the horrors already known. This provided new elements to comprehend the violence dynamics of such a bloody actor.

References

Bowker, Geoffrey. Memory Practices in the Sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

Jaramillo-Marín, Jefferson. “Reflexiones Sobre Los ‘usos’ Y ‘abusos’ de La Verdad, La Justicia Y La Reparación En El Proceso de Justicia Y Paz Colombiano (2005-2010).” Papel Político 15, no. 1 (2010): 13–46.

Olarte-Sierra, Maria Fernanda, Diaz del Castillo, Adriana, Pulido Ronchaquira, Natalia, Cabrera Villota, Nathalia, and Suarez Montañez, Roberto. “Verdad E Incertidumbre En El Marco Del Conflicto En Colombia: Una Mirada a Los Sistemas de Información Como Prácticas de Memoria.” Universitas Humanística 79 (2014): 233–54.

[1] The result of this process, known as the Peace and Justice Law, that was signed with the paramilitary group known as AUC (United Self-Defenders of Colombia) was controversial. For many, it did not constitute a peace and justice process, given that the focus on truth was solely judicial. Little to no attention was given to efforts towards truth that were not directly related to a juridical process for the demobilized paramilitary (Jaramillo-Marín 2010).

[2] On 24 November 2016, the FARC guerrilla group and the Colombian government signed a peace agreement. After decades of on-going confrontation, both parties decided to cease fire and to work jointly in achieving what has been called “the end of the conflict and the building of durable and stable peace”.

[3] To give a sense of the magnitude of the conflict, Colombia’s population is 49,691,660 as of March 26th, 2018.