Preface: this is the first in a series of posts by scholars who attended the Anthropocene Campus Melbourne, an event hosted in September by Deakin University as part of the larger Anthropocene Curriculum project. Over the four days of the Campus, 110 participants from 49 universities (plus several art institutions and museums) attended keynotes, art exhibits, fieldtrips, and workshops based around the theme of ‘the elemental’.

In hindsight, the Anthropocene Campus Melbourne can be understood as a four-day attempt at bringing the Anthropocene, that curious container of hyperobjects, to our senses through the elemental. Lying far beyond our abilities of representation and resolution, hyperobjects are omnipresent objects or processes that permeate our lives, gripping us with and into their “always-already” (Morton 2013). Though abstract and planetary in scale, hyperobjects sometimes ooze into our fields of perception and lend parts of themselves to the senses.

In what follows, I want to attune to the Anthropocenic oozing of the Campus, thinking through Kathleen Stewart’s evocative idea of ‘atmospheric attunements’ (2011) to examine three “pockets” within the event. Pockets, Stewart suggests, are space-time-places where potency, potentiality, and possibility flicker, while the impending reactions of matter and event charge the air. Pockets are made of intensities but also whispers and feelings, to be sensed in a “state of attention that is also an impassivity” (Stewart 2011, 446). Pockets are what happens at the interstices of embodiment and theory, a “space opening out of the charged rhythms of an ordinary” (Ibid, 447).

By practising the mode of attunement prescribed by Stewart across the three spaces, I found myself face to face with the ethics, sounds and quanta of the Anthropocene.

1. Breathing and becoming molecules

In the Air and Flesh stream, led by Alison Kenner and Eben Kirksey, we begin by breathing/coming in touch with our indoor comfort climate. Kenner, whose work grapples with the experiences of asthma and asthmatics in the United States, is well aware of the politics of our immersive medium. She invites us to delve into the sensorium that opens itself up to us in breath.

In rhythmic repetition, we soon start sensing what hung just beyond our flesh: the air. Kenner choreographs the movement of air into and out of our bodies, sending it deep into the pits of the lungs to touch the diaphragm, asking it to be held, released, brought back, felt.

As it turns out, it is much harder to hold air out, than it is to hold it in. Slightly heady, I think to myself: “This must be anaerobic time.” I wonder if air goes into bones, into rocks, into earth.

Next, we stand up to breath-walk. Bodies, lungs, skins all rise into the air. In gaseous state, we diffuse into the room, softly colliding and redirecting each other with the invisible skin enclosing our flesh. We cross paths in circles and lines, and come into fortuitous alignments. A steady asynchronicity emerges in the room.

Finally, Kenner gathers us into circles. She invites us to extend our arms and form bonds with neighbouring bodies. Flesh-to-flesh and porous, we begin swaying to the inhales and exhales that tighten and loosen our bonds.

Moving each other’s limbs, I viscerally realize that we all breathe differently—different lungs, different airs—an insight that Kenner impresses in her own work (see Kenner 2018). This final, entangled sway was a potent reminder of the importance of trans-corporeal ethics (Alaimo 2010) that takes shape when material agency is realized and recognized across bodies, place, and substance as a precursor to an elemental ecocriticism that was being developed throughout the Campus.

2. Disquiet of flesh

The hybrid botanical creature confronts the Testing Grounds visitors with questions of what it means to be a human, and what a possible future of genetic modification and extraordinary species might look like.

The Testing Grounds is a temporary creative space in the Southbank neighbourhood of Melbourne. The space itself is both camouflaged and conspicuous amongst its neighbouring buildings, most notably the Victoria Arts Centre (VAC), with its hard concrete face, towering 162m steel Spire and position on the city’s (aptly named) arterial roadways. The Testing Grounds was established on what had been deemed empty land. Previously, it had been home to the Melbourne YMCA building and provided a gathering place for those involved in building the VAC. A book chronicling the development of the Centre notes that the purchase of the “Y” brought significant changes to the project atmosphere. Bringing together builders, architects, engineers and contractors “it broke down the ‘us’ and ‘them’ feeling” (Fairfax, 2002).

Hello Pony encourages visitors of the Mothers and Future Humans visitors to explore their ecosexuality.

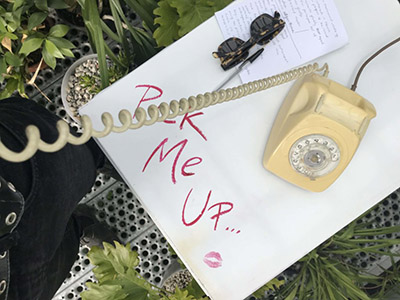

The Air/Flesh collective ambles alongside the Yarra River and reassembles here for the afternoon. We look into the eyes of Patricia Piccinini’s m/otherworldy Bootflower while another flower voyeuristically records our interaction. In the bathroom stalls, I privately experience my own ecosexuality, in phone sex with a plant.

In a corner of the grounds sat two badly injured pianos. I wondered what catastrophe(s) the pianos may have survived. I cajoled one of the pianos into sounding, using its own broken keys as instrument.

Here is a snippet from our conversation.

The quality of a piano is directly related to the species and cut of wood used to make it. Sometimes, the wood is dried and sent across continents and oceans before its shaped to fulfill a musical purpose. When built pianos are shipped from place to place, they acclimate to their new environments, sometimes warping and shedding their laminates. In a sense, the piano is alive and continues to be, even in this state of distress. How much more force can we put into containing the wood? The wood sounds wretched and defiant. This apocalyptic piano is tired.

3. After the end of the world

Two badly injured pianos

In their closing keynote on ‘transmutation of the elements, radioactive refugeeism, and alchemical wanderings’, Karen Barad re/turns us to our inherited futures passed. Frustrated with the doings of their beloved physics, Barad set out to retrace the legacies of Nuclear Physics in its smallest bits, to reunite it with meaning again.

I find myself folded forward to try to take in more of Barad’s artful primer on Theoretical Physics and Quantum Field Theory. Barad is carefully pulling physics through itself to dismantle the idea of the discrete divisions that separate a past and present, here and there, other and self.

Central to Newtonian physics, is the idea of the void: a background against which matter takes its place. The void does not have matter/doesn’t matter. This, Barad says, is the logic at the heart of occupation and the expansion of empire. It is an act of a/voidance of the human and the non-human and of relations, times, histories, possibilities in a place, that makes for conquest and Colonialism, or, as they explored in their talk, the rendering of an island as the test-site for nuclear warfare.

But as Quantum Field Theory has it, the void is always in motion, filled with infinite virtual im/possibilities of life, death, being, non-being, time and matter. A virtual particle can emerge into being/life when energy is put into the void, and can slip back into non-being, emitting that energy.

Barad shows us how, in the heart of the void, the emotional life of a ‘self-touching electron’ in a vacuum of infinities queers any notion of continuity, and unhinges matters of time and space. There is laughter in the room when they read a quote from Richard Feynman, who expresses horror at the perverse life of the electron and proposes his theory of Renormalization, dressing the deviance of the electron with the infinity of the void so that the particle can be captured in time and space. They call this “the electron in drag” (Barad 2018).

Inside the void, all possible histories are im/possible at the same time. The room is charged.

Pockets, like the vacuums of Quantum Field Theory, are spaces in suspended time where events and matterings surface into existence given the required energy. The campus was an activating moment that stretched over four days, where potential and possibility multiplied as we entered and left rooms, sounded and listened, turned, attuned, returned and remembered. The force created with the bodies and thoughts at the Anthropocene Campus Melbourne and its various pockets, propel attunements towards movements, and sensing towards knowing. Here, a community of care was cultivated through communal dis/orientation around the unscripted contingencies and irreversibilities of the Anthropocene.

References

Alaimo, Stacy. 2010. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment and the Material Self. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Barad, Karen. “After the End of the World: Transmutation of the Elements, Radioactive Refugeeism, and Alchemical Wanderings.” Keynote Lecture, Anthropocene Campus Melbourne, Melbourne, 6 September 2018.

Fairfax, Vicki. 2002. A Place Across the River: They Aspired to Create the Victorian Arts Centre. South Yarra, Victoria: Macmillan.

Kenner, Alison. 2018. Breathtaking: asthma care in the time of climate change. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Morton, Timothy. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2011 “Atmospheric Attunements.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (3): 445-453. doi 10.1068/d9109.

1 Trackback