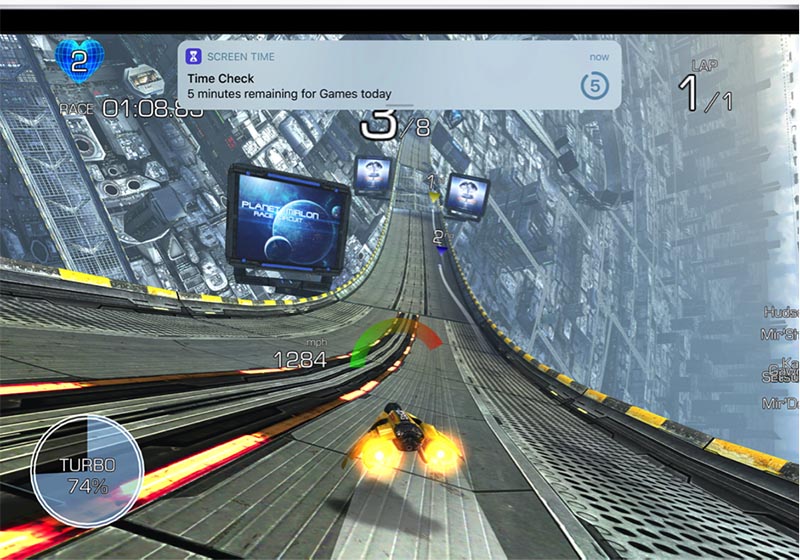

Screen Time app. Credit: Apple Press Kit

Auto-playing videos. Bottomless social media newsfeeds. Accentuated “I consent” buttons. The internet may appear as a Choose Your Own Adventure, but some pathways and actions are more enticing than others. Persuasion has become part of the online furniture and is largely by design; central to the architecture of user experience (UX) is the use of behavioral and social psychology to make particular aspects of digital products or services engaging and easy to use.

But when does persuasion become manipulation? In the last decade, the answer to this question has largely been guided by the term “dark patterns”. Dark patterns was coined by designer Harry Brignull to mean any UX feature that tricks the user into performing an online action they did not intend. On his website, Brignull lists different types of dark patterns with amusing titles. There’s “Roach Motel” to capture when a user finds it difficult to escape a certain situation (e.g., cancel a subscription), and “Privacy Zuckering” where the user is tricked reveal more information about themselves than they have to. Underlying each dark pattern is a contention that the user has been unduly coerced by the platform or designer.

My doctorate research on technological disconnection disputes the darkness of a dark pattern, demonstrating situations in which people actively want to be manipulated by their phone in order to have more control over their lives. One example is Freedom, a mobile and web app that limits access to social media. On the surface there is nothing “free” about Freedom at all, unless the app is situated in wider tech-backlash discourses where social media is conveyed as “addictive,” preying upon users’ psychological weaknesses. What Freedom frees users from is their compulsive tech habits and time lost mindlessly scrolling social media. Freedom therefore begs the question: what is “dark” about a design feature that protects people from their impulses?

Freedom app, blocking access to Instagram. Credit: Freedom Press Kit

Some scholars believe that dark patterns become more acceptable when consent is provided by users, but I argue that it is instead necessary to reframe persuasive design. There is more to say about persuasive design than potential infringements on personal liberty.

The problem is that the term dark pattern frames design too simplistically. The word “dark” foregrounds the moral aspects of UX design, conveying certain restrictive designs as evil or harmful. The issue with this frame is that it brushes over nuances when users desire a lack of choice (the aforementioned Freedom app) or when similar coercions are imposed on the user to incentivise behaviour (e.g., badges and unlocked features in wellbeing or exercise apps). In short, the framing of patterns as ‘dark’ oversimplifies the ethics of design into black and white categories, missing the often grey area that design operates within.

Anthropologist Nick Seaver (2019) acknowledges the murkiness of persuasion when comparing persuasive design to a digital trap. Although the metaphor of a trap brings to mind something sinister, it enables Seaver to more broadly theorize about social policies and political infrastructures that operate as traps in slow motion, placing people in vulnerable positions to predatory forces that appear benign. By shifting the point of enquiry from possible coercion to the wider social function of design, Seaver demonstrates the prevalence of persuasion across society.

A Foucauldian pattern

I would like to suggest another frame for persuasive design based on Michel Foucault’s theories of power. Foucault was a 20th century social theorist and historian of ideas who uncovered the changing dynamics of power throughout human history. One of Foucault’s major contributions was documenting how power had shifted from a unilateral force imposed by the sovereign state to a disciplinary power generated by discourses, norms and architectures. Taking a Foucauldian perspective of power, websites and apps with digital architectures operate as conduits for power to discipline and shape the behaviour of users. By meticulously tracing the history of human subjugation via dynamics of power, Foucault was an original observer of the way people’s experiences could be subtly shaped beyond cruder and more obvious forms of control.

Michel Foucault. Credit: Nemomain, available on Wikimedia Commons

Foucault was less interested in the force of power and more in how certain actions of power can be justified. Foucault’s concept of savoir or power/knowledge is helpful here. Foucault argued power and knowledge constitute each other, meaning knowledge is an exercise of power, and power is conditioned by what is deemed acceptable knowledge at the time. It is in UX design studios where knowledge of users are jotted down onto post-it notes and persuasive designs are wireframed through software and tested in A/B trials. We might call these mixes of power/knowledge a Foucauldian pattern of design. If a dark pattern claims a general use case scenario where a user is forced into an action they did not intend, a Foucauldian pattern denotes a general use case scenario where the user is persuasively steered to an end that is justified by wider discourse. Take Apple’s Screen Time as an example. One of the functionalities of Screen Time restricts the use on selected apps and games and sends regular reminders to users of the imminent constraint. Screen Time has largely gone unnoticed by critics of UX because of wider productivity and wellbeing discourses. These discourses paint excessive online time as unhealthy and subsequently valorize an otherwise coercive UX design feature.

Screen Time app notification. Credit: Apple Press Kit

The point of a Foucauldian pattern is not to identify where persuasion becomes coercive, but to draw attention to the instances where the disciplining of user behavior goes largely unnoticed. Throughout my research on digital disconnection, I’ve identified a range of such scenarios. In the spirit of Harry Brignall’s entertaining naming conventions, here’s a list of a few:

| Surfshaming | The act of guilting the user into spending less time on their phone. When notifications are provided to the user in a manner that shames how much time they spend on their phone. |

| Wake and partake | Where the default settings of an app or platform are oriented towards the encouragement of physical exercise or wellbeing related activities. |

| Digital straitjacket | The imposition of limits on certain apps or functionalities. |

| Hide the cookie jar | Making flagged apps harder to find with the intent of dissuading access. |

| #offthegrid

|

Where the user is encouraged to share their time away from their phone via their social media channels. |

These Foucauldian patterns are neither light or dark but ambiguously flooded with shades of grey. A digital straitjacket may appeal to some people and annoy others. The point is not to moralize design but reflect on the legitimization of its coercive and productive power. Foucault himself was a contradictory and complex thinker who rejected any universal claims regarding truth, humanity, or objectivity in favor of historical specificity. To evoke Foucault in the context of design is to largely bypass notions of right and wrong that often muddy debates concerning design ethics; instead interrogating the contexts where disciplining the user is accepted, even encouraged. Even Foucault in his later life undertook self-discipline in pursuit of his own transformation. In the late 1970s and early 80s Foucault shifted his focus to studying and practicing asceticism; the only ‘ethics’ Foucault was ever interested in developing was an ethics of self-care.

Today, the self-care industry is booming with persuasive design providing the underlying mechanisms of change. Foucauldian patterns are the underscrutinized design features that enable a dynamic reconfiguration of the user’s surrounding virtual environment, serving wider self-care trends such as digital minimalism (Newport 2019) and happiness optimization practices (Dolan 2014). Persuasive design also enables underlying behavioral markets (Zuboff 2019) that benefit from the continuous tinkering of behavioral architectures. It is this grey area of self-optimization and wellbeing that persuasive design and the steering of user behavior is legitimized.

Should we be concerned about the degree of persuasion embedded in the digital environment? To answer requires a reflection about how often we welcome the subtle shaping of our lives.

References

Dolan, Paul. 2014. Happiness By Design: Change What You Do, Not How You Think. New York: Avery Books.

Newport, Carl. 2019. Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World. London: Portfolio.

Seaver, Nick. 2019. “Captivating algorithms: Recommender systems as traps.” Journal of Material Culture, 24 (4): 421-436.

Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Struggle at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books.

1 Trackback