When I agreed to write this post in January, I could not have imagined that I would be doing so in quarantine. The state of the coronavirus continues to escalate. I do not yet feel ready to engage with this current event in this blog post, but its weight is present and felt in the writing.

On January 17, 2020, the National Bureau of Statistics of China published 2019’s annual economy data (English here). Among the lists of numbers from the world’s second largest economic body — lists that included agricultural and industrial production, the growth of the service sector, and consumption and employment, among others — the section of data about population is what dominated the media’s attention.

During the press conference, a Financial Times reporter asked about the lowest-recorded birth rate (10.48‰), its relation to the “two-child policy” and its impact on the (future) economy. This question led to an elaborate response from the bureau commissioner, in an attempt to veil the journalist’s critique (that the termination of the one-child policy failed to reverse structural aging) and place things under a more positive tone: although the rate is low, the actual number of newborns is still pretty high.

This is not breaking news for those who are familiar with China’s population policy. Many—from media critics and demographers to senior care consultants and entrepreneurs—find the newly-released numbers rather in line with the prediction. The New York Times, for example, within a few minutes of the Bureau’s announcement of the data, posted an online article where the Bureau’s numbers were indicated as conclusive evidence that verified the projection of China’s “looming crisis” of population aging and shrinkage.

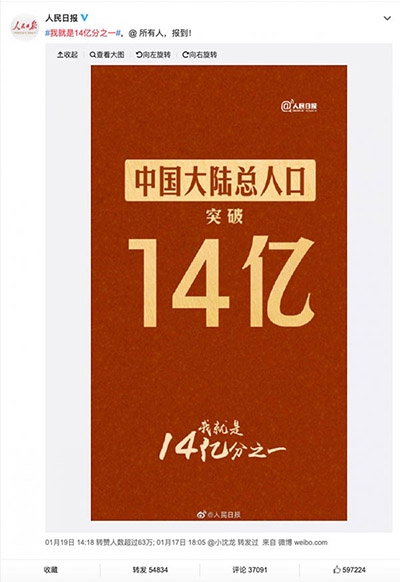

And yet, on Weibo (a popular Chinese social network), People’s Daily (the mouthpiece of the Communist Party of China) took a different approach to the data. Rather than focusing on fertility rates or drawing curves, this approach highlights the size of the population. Based on the Bureau’s press release stating that by the end of 2019, the total population of mainland China had “steadily” grown to 1400.05 million, the People’s Daily, tweeted on Weibo (and I can only roughly translate the sentiment): “#I am one of the 1.4 billion#. @ All people, reporting!” #我就是14亿分之一#,@ 所有人,报到!

A red and gold poster from the People’s Daily Weibo account. In bold Yao Ti font, it reads: “China’s population breaks 1.4 billion.” In stylized calligraphy, it reads: “I AM one of the 1.4 billion.”

By mixing in social media grammar (using “at/@,” or “mentioning”), the Weibo post does the work of diluting rather hardcore propaganda into something lighter and approachable. That is, with the space between “at” and “all,” although the coded “at” does not really function in the programming language, it works in the sentence as a casual interpellator that calls into being a vast “all”—the all of the 1.4 billion. More than a cold “hey, you!” the “@ all,” at once calls into being a subject of 1.4 billion, as well as a sense of belonging to a collectivity.

In addition to the text, the poster truly brings the message home. On a rust-colored rectangular canvas, three lines of Chinese text appear in golden-colored Yao Ti font, occupying the upper half of the poster, recapitulating that “the total population of Mainland China broke 1.4 billion.” While at the bottom, two smaller lines in firm and powerful calligraphy read an assertive: “I am one of the 1.4 billion (wo jiushi shisiyifenzhiyi 我就是14亿分之一).” The contrast of the font seems to emphasize, once again, that while the number may appear to be objective, it also reads with feelings; it seeks to invoke in its readers a sense of pride, collectivity, and constitution.

Though not without criticism or mockery, hundreds of thousands of replies filled the comments section, echoing the hashtag’s call: “I am one of the 1.4 billion.” The fact that a number—the sheer size of the population—can be mobilized to invoke public feelings, especially a feeling of constituting, poses questions to those of us who are too often comfortable in making the leap from seeing one being among the “population” as being governed—and hence dehumanized—by the logics of biopolitics. Devices of biopolitical rationales, such as notions of the “number” and “statistics,” are considered dirty because they stand in for and erase real humans. Susan Greenhalgh, an anthropologist specializing in China’s population policies, rightfully points out that it is through the creation of different subjects, rather than coercion (the predominant way in which effects of such policies are portrayed in the West due to Cold War legacies) that China’s population policies can be thought of in terms of biopolitics in the first place (Greenhalgh 2010). Implied in her argument is the idea that population serves as a foundational political concept in China — one which gives rise to forms of everyday experience. This is echoed in many conversations I have had in my dissertation fieldwork, which looks at corporate responses to population aging in urban China. It is beyond the scope of this post to investigate the relations between population policies and discourses and categories of subjects (for such projects I want to point to works such as Greenhalgh and Winckler 2005, Lam 2011, and Thompson 2012). Rather, here I want to think through my fieldwork and to reflect on more mundane stories: what does it mean for one to feel and to constitute a population?

My ongoing fieldwork—though temporarily suspended due to coronavirus—takes place in a senior care company that runs several assisted living facilities in Nanjing, China. I work primarily with the customer service, sales, and branding departments in the headquarters, while also visiting facilities and engaging with “frontline” care workers, social workers, and senior residents, as well as their families—the clients. One of my more regular tasks is facilitating a quarterly satisfaction survey. In the past, while the survey had been performed using in-person interviews, it was focused on the rather strict categories of experience of life inside the facility: food, service, activities, and complaints. The managers brought me on to the “team” because they felt that the survey needed fresh eyes—and who could be better than someone trained in asking questions, yet outside the system?

Conducting the survey provided me with abundant opportunities to talk to senior residents in length. Anthropological and sociological research on aging in China has highlighted the home vs institution debate, where issues of ethics, care, kinship, and modernity all come into play (Zhang 2006, Chen 2016, Fong 2004, for example). In these studies, China’s demographic aging is often laid as the background against which real, smaller humans act. That is, population is set as the context — the big, inhuman thing that is out there, beyond daily life. Yet, what I found fascinating is that real life, ethical choices, and population are not segregated spheres for the majority of my senior interlocutors.

More often than not, when I asked them why they moved into the facility and what brought them here, they would volunteer the story of how they and their children came to the decision for them to leave home. Sometimes the story was one of liberation from generational, household duties; sometimes the story ended on a happy tone of how they overcame doubts and started to actually appreciate life in the facility; and sometimes it became a story without end, one of getting adjusted to the state of constantly adjusting, to the come-and-go of people (residents or care workers), to the change of food flavor, to bodily decline, to other people’s bodily decline, and above all, to the shift from home to a facility.

It is in those moments of adjusting to and acceptance of change that I learned about demography. Many interlocutors, satisfied or not, would tell me that now China is faced with this thing called “population aging” (renkou laolinghua人口老龄化). With so many older people who need to be attended to and a shrinking younger generation who can no longer afford to give support, institutional senior care is and will be the trend. Most of my senior interlocutors are well above the age of 80. And not unlike my corporate interlocutors, population aging is part of their daily vocabularies. They read about and reflect upon population aging, and in doing so they connect their personal situation with the vast social transformation: they see themselves in the population. They feel and experience the population, while coming to terms with big changes in their own lives.

To be clear, I am not equating what was said with what was desirable for my interlocutors. And in fact, during many conversations, I have felt that their telling me stories—their thought processes and their takes on population aging—is at once a technique to convince themselves. And yet such telling and self-convincing is meaningful. By living within the population and by actively constituting—in the action of telling—the population, one becomes able to see the milieu of life (Mills 1959) in a different light. Moving into the facility, in this way, for many of my senior interlocutors, gains historical significance and necessity beyond individual and familial choice, and in turn makes such a choice personally meaningful.

Through the People’s Daily’s hashtag and my interlocutors’ use of population, I want to put forward a simple argument that in today’s China, population is felt. Growing up in a small town in China in the 90s, I am no stranger to such political cultivation of feelings. For instance, the number “1.29 billion” (shieryijiuqianwan十二亿九千万)—the size of China’s population at the time—was omnipresent in textbooks, speeches, TV programs, along with “9.6 million square kilometers” (jiubailiushiwan pingfanggongli九百六十万平方公里), the rough size of the land. These numbers circulated in the world as two metonymies of China. Calling upon them simultaneously summons a sense of vastness that translates into magnificence, pride, and most importantly, a sense of constituting. This sense of constituting is precisely what we see in my interlocutors’ personal use of population aging, as well as what is embedded in the hashtag, I am one of the 1.4 billion. Yet I spell out this simple argument anyway because I think this felt-ness of population makes possible a way of understanding population ethnographically: a way of understanding how population as subject-object (Foucault 2007) conditions (and gives language to) ordinary life. The sense of constituting, as we see in these examples, could have larger implications for how we understand population and demography not simply as statistics, but as statistics in the world.

To understand how the population is lived/felt is not to say that it is innocent. It does not mean shrugging off the violence that is and has been done in the name of the population, neither does it cancel out the inequality inherent in, for example, today’s policies that favor and promote corporate investments in response to population aging. Similarly, to say that one is a subject of the population is not to say life is not meaningful or agentive. Instead, it recognizes how decisions, choices, and feelings are made possible by and deeply intertwined with structural forces, and in my case, demographic transformation. Understanding how population prevails in everyday life, in a way, responds to anthropologist/sociologist/demographer Jennifer Johnson-Hanks’ call to be cautious about a “methodological individualism” (2008) by resisting the comfort we find in dichotomizing numbers and humanity. The case of population in China might just provide a valuable lesson about how population and life are mutually constituted.

References

Chen, Lin. 2016. Evolving Eldercare in Contemporary China: Two Generations, One Decision. New York: Springer.

Fong, Vanessa L. 2004. Only Hope: Coming of Age Under China’s One-Child Policy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977-1978. Translated by Graham Burchell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Greenhalgh, Susan. 2010. Cultivating Global Citizens: Population in the Rise of China. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Greenhalgh, Susan, and Edwin A. Winckler. 2005. Governing China’s Population: From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Johnson‐Hanks, Jennifer. 2008. “Demographic Transitions and Modernity.” Annual Review of Anthropology 37: 301–15.

Lam, Tong. 2011. A Passion for Facts: Social Surveys and the Construction of the Chinese Nation-State, 1900–1949. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

Mills, Charles Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, Malcolm. 2012. “Foucault, Fields of Governability, and the Population–Family–Economy Nexus in China.” History and Theory 51 (1): 42–62.

Zhang, Hong. 2006. “Family Care or Residential Care? The Moral and Practical Dilemmas Facing the Elderly in Urban China.” Asian Anthropology 5 (1): 57–83.