Sensory ethnography continually emphasizes that the sensorium is just as much a (product of) sociocultural practice as it is a biophysiological property of the human species (Pink 2015). Recognition of this point has prompted several shifts in ethnographic work. On the one hand, it has pushed ethnographers to include in their writing a greater discussion of how subjects engage with the world through their senses as well as how the putatively biological phenomenon of sensory perception is so highly variable across and within sociocultural milieux. On the other, it has inspired ethnographers to pursue media practices beyond text, particularly through ethnographic film or sound recording (Feld 1991). Regardless of form, this work has greatly increased the possibility for the reader, listener, or viewer to experience with their senses the social environment that subjects inhabit and where the ethnographer conducted fieldwork.

At the same time, current practices in sensory ethnography are quite limited in their ability to capture the full breadth of what it means to consider a social environment as a sensory experience. Of these many limitations, one of the most significant is the fact that the vast majority of current work takes the form of a mono-directional sensory experience taking a path proceeding from:

- the field site and its sensory features,

- to their capture by an ethnographer,

- and terminating in their delivery to the reader, listener, or viewer through ethnographic media.

This is largely because nearly all experiments in sensory ethnography have been limited to what avant-garde electronic music composers refer to as “fixed media,” or media forms designed exclusively for playback.[1] Film and sound recording are the canonical examples of fixed media, though the term is perhaps just as apt for describing text-based ethnographic writing as well. Formally speaking, fixed media are defined by the fact that:

- the timeline and pacing of sonic, visual, or other narrative events are the sole discretion of their producer;

- they do not respond to the viewer or listener in real time; and

- despite the illusion of producing different sounds or images at different time points, they do not change as a result of playback.

As basic as this point is, while ethnographic fixed media allow the viewer or listener to see or hear a social environment, these fixed media are unable to see, hear, or respond to the viewer or listener. As a result, the viewer or listener does not experience the basic consequences and contingencies that arise as other human beings see, hear, and otherwise sense their presence, an experience that is a fundamental element of sensation as a cultural practice. To put it very directly, people are not fixed media.

The sequence of events of an ordinary human interaction inherently lacks the consistency of the same within fixed media. Likewise, human beings lack the imperviousness of fixed media as they tend to respond to each other and the world because of what their senses bring to their attention. Nevertheless, fixed media are the dominant media form social scientists and humanists use to depict human practice. If the goal is to portray human beings as they are, the dominant media form used to do this in the humanities and social sciences is incommensurate with the basic indeterminacy and reactivity of the subject they attempt to represent: the human being.

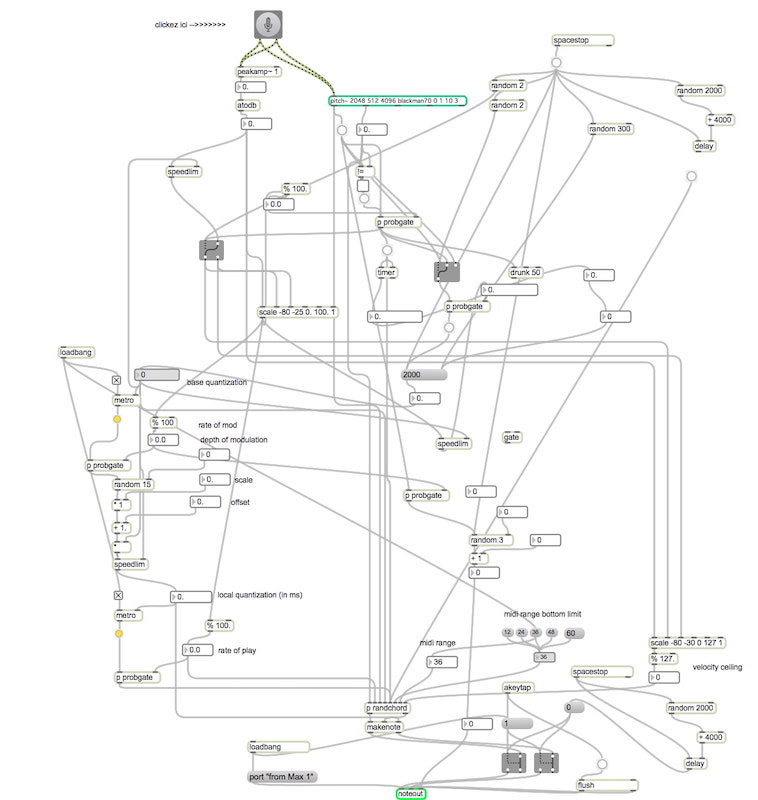

Though fixed media are poorly suited for capturing and delivering the experience of how members of a given social world respond to one’s presence in real-time, many other, newer forms of interactive, algorithmic media are quite able to accomplish this. Over the past decade or so, my work has focused on the design of such media and their use as a means of ethnographically performing culturally-specific forms of human interaction through sound. At the center of this work has been a system I designed called “Maxine” (Banerji 2016). Drawing on my ethnographic work as a performer of free improvisation (a postwar, avant-garde musical practice), I have designed Maxine to perform as a collaborator with human players active in this form of music-making.[2]

Maxine, an algorithmic ethnography “written” in the Max/MSP programming environment

Excerpt of a duo improvisation with Maxine (guitar) and Lori (trumpet) [3]

In addition to designing the system to spontaneously generate new sonic materials in the manner of a typical improviser, I have built the system to listen and respond to other performers like a human player in this musical subculture would. In effect, the system is a bi-directional, interactive, algorithmic, sensory ethnography in that it delivers the sound of this subculture while also delivering the experience of a member of this social world listening and reacting to its interlocutors in real-time.[4] Hence the system provides what is essentially missing in current experiments with multimodal ethnography by allowing its interlocutor to experience how their sonic actions have a pragmatic consequence on the sensory outcomes of the interaction.

When The Argonauts Listen

Most of my fieldwork has focused on asking improvisers to play with Maxine and compare the system to a human performer.[5] That is, most of Maxine’s interlocutors have not been fellow ethnographers, but rather the people whose practices Maxine performs. For the most part, this consists of arranging private playing sessions for musicians to improvise with Maxine and then discuss how this experience compares to playing with another human improviser. This kind of ethnographic feedback technique is not unique. Many ethnographers have conducted similar experiments by asking those they have depicted to critique the ethnographer’s depiction (Feld 1987; Harper 2002). Likewise, moments of feedback often happen without the ethnographer’s intention as ethnographic media, like any kind of media, circulate and come in contact with an audience that is itself on-screen, in the recording, or in the text (Madison 2005; Fassin 2015; Abu-Lughod 2016). The difference here, however, is that an encounter with Maxine is more than just a critical appraisal of how well I have depicted what free improvisation sounds like as a social world, but how well I have built Maxine to perform the use of sonic sensation in response to novel material and do so in the way that a typical improviser would.

Because Maxine listens and responds to what musicians play, playing with the system is a slightly different experience for each player that encounters it. Even I as the designer am unable to predict what the system will do in response to different material when I perform with it.[6] Despite this variability, however, the system’s overall working procedures remain the same each time.[7]

For example, in this clip, both the system and the human performer are audibly interacting with one another and frequently display sonic attentiveness to each other as the piece proceeds. Listening takes place not only as the receipt of sonic information but in an immediate behavioral response that confirms that the information has been received.

Excerpt of a duo improvisation with Maxine (synthesizer) and Sten (drum kit) [8]

By contrast, in this example, very little audible interaction takes place between the system and the human performer. While on some level it sounds as though the two are not listening to one another, it is important to note that listening does not necessarily manifest itself as a display of attentiveness (see Goffman 1966; Bakeman and Brownlee 1980).

Excerpt of duo improvisation with Maxine (synthesizer) and Kevin (double-reed) [9]

From one view, Maxine’s inherent instability raises questions about the efficacy of interactive media as a tool for ethnographic depiction and performance. It would be quite disconcerting if every time we opened up Malinowski’s Argonauts to the same page, different words appeared, or worse, that these words were in response to something that had just taken place in our present as if a magical Trobriander were rewriting the book on the fly as we read. We would be unsure as to whether we are really encountering Malinowski’s cohesive rendering of the Trobrianders as a whole or an individual Trobriander with the power of time travel. Most of all, no two readers of the book would concur on what they read since they would have read fundamentally different books. In this way, the instability of interactive ethnographic media like Maxine underscores the value of fixed media representations. Despite the incommensurability of fixed media with the inherent dynamism of the human beings they depict, their stability enables a coherent discussion because the ethnographic media object in question is not constantly shifting before us.

Yet as many ethnographers likely recognize, the idea that a single ethnographic monograph, film, or sound recording is, in fact, “singular” and fixed is a bit of an illusion in practice. The instability of interactive ethnographic media like Maxine actually resonates quite strongly with the instability of ethnography all the way from fieldwork to readership. Regardless of the fixed media form chosen for publication (i.e., text, sound, or film), the researcher’s primary data is often a result of relatively indeterminate interactions with their subjects in the field (see Tedlock and Mannheim 1995). As is the case with Maxine, one does not know how subjects will respond to the researcher’s presence, behavior, and overall goals. Similarly, no two ethnographers will collect the same data from fieldwork conducted in the same place because as individuals they are unlikely to elicit the same social behavior through their presence. The same is true for the seemingly “final” moment of the ethnographic text as it encounters the reader. While there is no magical Trobriander rewriting the book each time we open it, our experiences and moods shape what we understand when we read. Such issues may now be commonplace in contemporary thinking on ethnographic practice, but interactive media forms like Maxine make all of this abundantly clear by emphasizing this instability as a constant in the study of sociocultural practice.

From Criticism to Practice

Among many other reasons, anthropologists (alongside others in the social sciences and humanities) are quite right to be skeptical of a potential techno-utopianism lurking in what I am proposing. They are absolutely correct to note—as a large bibliography now does—that algorithmic systems encode the biases of their creators either through their very design or through the implicit partialities of the datasets used to train them (see, among many other examples, Nissenbaum 2001; Suchman 2006; Benjamin 2019). All of this is true for Maxine: my construction of the system is not impartial. Nevertheless, for all intents and purposes, there is no major difference between the partialities I have encoded in Maxine and the partialities inscribed into any other form of ethnographic writing, film, or sound production. Moreover, media forms like Maxine are able to accomplish something categorically different than their predecessors in fixed media. If we are to take seriously the basic starting point of sensory ethnography that the sensorium is a cultural practice, it only makes sense to continue to find ways of including technologies like Maxine in this work.

Nevertheless, the capacities to build a system like Maxine are still not at all a regular element of how anthropologists are trained. At a recent talk I gave about Maxine, an audience member asked how I would address the fact that most ethnographers are not trained to use the basic computational and electronic tools required to build a system like Maxine. While this is a fair and frequent question, I admit that in the time that I have been doing what I have in designing Maxine and other systems, I have often wondered why my project remains so unusual within anthropology or really any other field driven by ethnographic methods. It is particularly surprising given the frequency of discussions of sensory ethnography and their emphasis on the importance of not only discussing sensation as a cultural practice but of methodological experimentation in order to find new ethnographic media for portraying or performing the mutually constitutive relationship between the sensorium and specific forms of social life. I would really say that the present moment—if not the last ten years or more—may finally be the time to devise a plan to enable more anthropologists, particularly those interested in sensation, to be able to build such systems. After all, it is rather regularly that those who join the field have training in technical fields and thus would not face a steep learning curve in this direction. For those that do not have these backgrounds, the learning curve for building such systems has substantially flattened over time and only continues to do so.

Footnotes

[1] The term has its origins in the practice of “tape music,” which is, quite literally, a musical composition intended solely for playback as tape. As tape gave way to other formats, including digital forms no longer permanently linked to a single physical medium, fixed media became the dominant term. A history of this term and its definition is yet to be written, but for now, see (Collins et al. 2013, 125-127).

[2] Maxine is by no means the first system designed based on free improvisation; George E. Lewis’ Voyager is arguably the first (Lewis 1993, 2000). While similar in concept to Voyager, Maxine is distinct in design and implementation.

[3] In this clip, we hear an improvised duo of trumpet and guitar in which the two players frequently respond to each other’s playing resulting in an atonal, pulseless texture frequently featuring pitchless sounds.

[4] In Ian Bogost’s terms, Maxine uses “procedural rhetoric” as a technique of ethnographic depiction (Bogost 2010). This is in the sense that it uses a collection of computational procedures to make claims about the way that a particular social practice—free improvisation—feels. While procedural rhetoric is indeed an apt descriptor, both the concept and Bogost’s account of it overemphasize the role of computation at the expense of the sensorial features of an experience like playing with Maxine (or any other improviser).

[5] For reasons of space, I will not include commentary from improvisers on Maxine here, but a brief overview of this feedback can be read elsewhere (Banerji 2016, 2021).

[6] This is in part because the system uses a handful of random processes, but largely because I built the system to listen for pitch within an environment in which pitch is often not clearly discernible. While the system “hears” the same pitch for the same unpitched material each time, there is no way for a human being to intuitively understand how it hears these “pitches” from these materials (see Banerji 2016).

[7]While machine learning and other techniques are quite popular, I did not include them in Maxine’s design.

[8] In this clip, we hear an improvised duo of drum kit and synthesizer in which the two players can be heard audibly and immediately responding to each other’s playing as the piece progresses.

[9] In this clip, we hear an improvised duo of a double-reed instrument and synthesizer in which the two players do not sound as if they are obviously reacting to each other’s contributions, almost as if they are not listening to one another.

References

Abu-Lughod, Lila. 2016. “The Cross-Publics of Ethnography: The Case of “the Muslimwoman”.” American Ethnologist 43 (4): 595-608.

Bakeman, Roger, and John R. Brownlee. 1980. “The Strategic Use of Parallel Play: A Sequential Analysis.” Child Development 51 (3): 873-878.

Banerji, Ritwik. 2016. “Balancing Defiance and Cooperation: The Design and Human Critique of a Virtual Free Improviser.” Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference: 48-53.

—. 2021. “Whiteness as Improvisation, Nonwhiteness as Machine.” Jazz and Culture 4 (2): 56-84.

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Bogost, Ian. 2010. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Collins, Nicholas, Margaret Schedel, and Scott Wilson. 2013. Electronic Music. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Fassin, Didier. 2015. “The Public Afterlife of Ethnography.” American Ethnologist 42 (4): 592-609.

Feld, Steven. 1987. “Dialogic Editing: Interpreting How Kaluli Read Sound and Sentiment.” Cultural Anthropology 2 (2): 190-210.

—. 1991. “Voices of the Rainforest.” Compact Disc. Salem, MA: Rykodisc. RCD 10173.

Goffman, Erving. 1966. Behavior in Public Spaces: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Harper, Douglas. 2002. “Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 13-26.

Lewis, George E. 1993. “Voyager.” Compact Disc. Tokyo, Japan: Avant Records. Avan 014.

—. 2000. “Too Many Notes: Computers, Complexity and Culture in Voyager.” Leonardo Music Journal 10: 33-39.

Madison, D. Soyini. 2005. Critical Ethnography: Method, Ethics, and Performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Nissenbaum, Helen. 2001. “How Computer Systems Embody Values.” Computer 34 (3): 118-119.

Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London, England: SAGE Publications.

Suchman, Lucy A. 2006. Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Tedlock, Dennis, and Bruce Mannheim. 1995. The Dialogic Emergence of Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.