First edition cover of 2010: Odyssey Two where the quote “all these worlds are yours except Europa…” is from.

Beneath Europa’s frozen surface is an ocean thought to contain twice as much water than that on Earth (Planetary Science Communications Team 2021). Above its surface, temperatures are lethal, ranging from -210 degrees Fahrenheit to -370 degrees Fahrenheit (Planetary Science Communications Team 2021). This is the same moon of Jupiter which harbored indigenous life in Robinson’s 2312 (and was protected because of it) (2012). The same moon that Russian cosmonauts were warned to avoid in Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two (1982) due to its geologically unstable nature (fig. 1). The moon named after a Phonecian Princess, who was made the first Queen of Crete after she was abducted and raped by Zeus.

These three anecdotes have more in common than just a name. They are all pieces of a puzzle I’m attempting to put together. A two-sided puzzle, Janus-faced and just as divided. On one side is Europa, her cracked, icy surface both uninviting and full of promise. One day this moon might be colonized by those with the power and resources to travel to her in the first place. On the other side of the puzzle is another icy place, far more familiar and already colonized – Antarctica. Together they touch on histories and promised futures of colonization.

Both, which are rather problematic.

What are the implications of colonizing uninhabited spaces?

Unless Robinson’s indigenous Europans are real, or we start giving penguins citizenship, both places are technically uninhabited. But both have also been at the center of colonization narratives (though not necessarily explicitly), which I will describe momentarily.

But before digging into such narratives, I want to ask: can colonies be established without colonization? What is a colony without an indigenous population?

By definition, a “colony” is a country or area under the full or partial political control of another country, occupied by settlers from that country. “Colonization,” on the other hand, is the action or process of settling among and establishing control over indigenous people of an area (“Colonization” 2017).

And a colony without an indigenous population would be a “settlement” – a place that has been previously uninhabited and where people establish a community. Except… consider the other definition of settlement, which in law is a resolution between disputing parties. Settlement of uninhabited spaces, such as Antarctica (or even Europa), are not free of contestation. In fact, based on historical information, it seems colonization of uninhabited spaces can’t occur without contestation. Previous research by social scientists has echoed the ethical questions surrounding human colonization and such debates often end up the focus of mass-marketed space films and literature (Smith 2019). Whether the location being colonized is inhabited or not, colonization is hardly a benign act. And even when an area might be natively unoccupied, it often becomes settled through colonization or colonization disguised as scientific exploration.

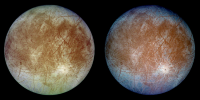

Once scientists discovered that Europa’s surface was mostly ice and one of the most likely places to harbor alien life in our solar system, the moon became a focal point of interest for exploration (fig. 2). Likewise, during the 1800s or what is known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Antarctica was at the center of attention in terms of research and scientific ventures. But along with these “scientific” ventures comes news articles titled “Grimes Jokes About ‘Colonizing Europa’ for a ‘Lesbian Space Commune’ After Elon Musk Split” (2021) and more serious pieces such as “The Next ‘Giant Leap?’ We Can And Must Send People To The Moons Of Jupiter And Saturn By 2080 Say NASA Scientists” (2021). As well, a serious interest in research of unoccupied spaces for their precious resources, such as the rare-Earth metals on asteroids or microbes in Antarctica for their “scientific potential” become a part of the colonial extraction involved in scientific colonialism.

Figure 2. Images of Europa. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/DLR

There is a longstanding legacy of scientific exploration for the sake of colonization across research stations of all varieties, and specifically, Antarctic stations, as mentioned previously (Mandel, forthcoming). In her ethnography (2017), Jessica O’Reilly argues that the extensive scientific population living in Antarctica has become the indigenous population and therefore settled it. O’Reilly describes how Antarctic residents use expertise as their primary model of governance and how the historical legacy and continued establishment of their occupation is also a road paved with contestation (O’Reilly 2017). She states that “Competing claims of nationalism, scientific disciplines, field experiences, and personal relationships among Antarctic environmental managers disrupt the idea of a utopian epistemic community [emphasis added]” (O’Reilly 2017).

A “utopian epistemic community,” in other words, a value-neutral community of scholars. Which is what I think – based on what I’ve seen during my time working in the commercial space industry and conducting ethnography at Spaceport America – that many imagine colonies in space will be and have imagined Antarctic colonies to be in the past. But the rise of the commercial space race – or the rapid advancement of privately run space organizations since the creation of the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act – is not unlike that which occurred between nations making territorial claims over Antarctica throughout the 1900s. Making this imagined reality of a value-neutral community anything but realistic (Dodds 2006). If these companies meet their goals, the resulting colonies won’t be governed by expertise or even governments, they’ll be governed by the commercial corporations who put them there in the first place.

Beyond these complications, what are the implications of maintaining colonial projects in a supposedly postcolonial era? “Postcolonial” is another complex term. Some define it as the end of colonization, others such as Warwick Anderson argue that it’s an examination of the continued effects of colonialism, rather than its supposed end (Anderson 2002). Postcolonial can be a time period (after the colonial), a location (where the colonial was), a critique of the legacy of colonialism, etc. (Anderson 2002). Antarctic scholar Klaus Dodds stated that “The polar continent and surrounding Southern Ocean present a significant opportunity to think again about what Derek Gregory has termed the ‘colonial present’” (Dodds 2006). Likewise, Sanjay Chaturvedi described colonization of the polar regions as “an extension of a similar but much larger process emanating, at least to begin with, from Europe, and unfolding differently in various parts of the world” (Chaturvedi 1996: 39). The idea of scientific stations as extensions of nations as well as larger institutions is also emphasized in Megan Raby’s American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Raby 2017). Making such colonization of uninhabited spaces all the more dangerous in the way that they perpetuate the imperialist legacies of global leaders in science and technology. With all this in mind, the persistent colonial rhetoric surrounding the commercial space race – the demand by companies to create colonies off-world – is grating, to say the least.

Elon Musk has not been shy about his consistent plan to colonize Mars, even when faced with intense criticism for his motives (Harrison 2022; Brock 2022; Ongweso 2022). NASA has also maintained a streamlined vision for the Artemis missions to establish a long-term presence on the Moon (Dunbar N.D.). And Jeff Bezos predicts that people will one day be born in space and “visit Earth the way you visit, you know, Yellowstone National Park” (Hartmans 2021). And these are just the billionaires and large government organizations. If my research has taught me anything, it’s that the passion for outer space exploration and colonization remains a staple of human curiosity and exists in many of us.

I once had an audience member ask me during a webinar why I was still using the term “colonization” if I spoke so ardently about decolonizing space exploration. The answer is because commercial space companies are still throwing around the term, and I have no interest in making it seem like they’re not. So, I’m going to keep using that word – colonization – instead of settlement because settlement makes things appear just a little too benign. After all, the field of science and technology studies has taught us that scientific development and infrastructures are hardly neutral, and the colonization of the Antarctic and future colonization of other planets have been framed with scientific research as their founding rationale.

Now, I’m not the first to bring these issues up, and some scholars have even offered solutions to current colonial issues surrounding outer space development, such as Sheri Wells-Jensen’s case for disabled astronauts (2018) and D.N. Lee’s invitation to frame space narratives in a more inclusive manner (Zevallos 2015). Opening the dialogue to include indigenous and diverse voices is one approach to change with much potential, but I’m worried it won’t solve the systemic, historically-engrained, imperialist mindset behind commercial space and specifically American space ventures.

And I should note that I’m actually not opposed to the colonization of the Antarctic at all. In fact, I think focusing on polar development as opposed to human space exploration is a much better way of spending resources… if we’re going to be spending them on exploration in the first place. It’s just the way the human race tends to settle uninhabited spaces that I take issue with.

Returning to the question I posed at the beginning of this article – can colonies be established without colonization? Based on historical evidence and the present rhetoric of many commercial space organizations, one would think I would argue no. But actually, I do see stars lighting the end of the tunnel (to use a cheesy space metaphor).

Is it so ridiculous to imagine a world where instead of staking territorial claims through colonization, humans work together to develop settlement strategies that benefit all individuals and nations equally? I’m asking for more than just international collaboration, which Antarctic stations (and space stations) tend to manage well already. I’m asking for a complete and total change in how we maintain and divide our planet into territories owned by nations. What if the United Nations or a Ministry of the Future that does not yet exist (a term I take from a book by Robinson of the same title) declared that no land can be claimed by one nation ever again (Robinson 2020). Did you laugh when you read that? Or shake your head in disbelief? Did you ask yourself, “well, what about laws?” I asked myself that too, and came up with the simple answer that we would just have to make new laws, not unlike the laws of the sea, the Antarctic Treaty, or the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (and yes, I know they need to be edited).

But I don’t think this change should apply to just uninhabited spaces or other planets, I think it should apply to the Earth period. Universal law, combined with the removal of territorial claims-making.

Now that’s postcolonial.

Some might call the prospect Marxist, or even Anarchist. But I don’t think of it like that, I think of it as a recentering of global beliefs and values that have done nothing but divide populations and cause conflict. Like Charlene Carruthers says, we have to conjure up a vastly different world without apologizing for radical social changes (Carruthers 2018).

Figure 3. late 21: The Rape of Europa from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ (1606).

But if we do refocus global beliefs and values in such a radical way, where do we start? I think we should start with this. Acceptance of intense change. Complete global restructuring. Maybe even the creation of a Ministry for the Future – which would seek to include the voices of both present and future generations (Robinson 2021). And maybe we could stop naming our planets after stories about rape (fig. 3).

References

Anderson, Warwick. 2002. “Introduction: Postcolonial Technoscience.” Social Studies of Science, 32 (5/6): 643–58.

Bowenbank, Starr. 2021. “Grimes Jokes About ‘Colonizing Europa’ for a ‘Lesbian Space Commune’ After Elon Musk Split.” Billboard, September 29, https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/grimes-elon-musk-split-joke-colonize-jupiter-9638072/ [accessed August 23, 2022].

Brock, Jared. 2022. “Human Beings Will Never Permanently Colonize Mars or Even the Moon.” Surviving Tomorrow, August 8, https://survivingtomorrow.org/human-beings-will-never-permanently-colonize-mars-or-even-the-moon-caad45e6a49d [accessed August 23, 2022].

Carruthers, Charlene. 2018. “Hearing Assata Shakur’s Call.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46, (3 & 4): 222-225.

Carter, Jamie. 2021. “The Next ‘Giant Leap?’ We Can And Must Send People To The Moons Of Jupiter And Saturn By 2080 Say NASA Scientists.” October 13, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiecartereurope/2021/10/13/one-giant-planet-leap-we-can-and-must-send-people-to-the-moons-of-jupiter-and-saturn-by-2080-say-nasa-scientists/?sh=2d5da29c1b06 [accessed August 23, 2022].

Chaturvedi, S. 1996. The Polar Regions: A Political Geography. Chichester: John Wiley.

Clarke, Arthur C. 1982. 2010: Odyssey Two. New York City: Ballantine Books.

“Colonization.” 2017. In Oxford English Dictionaries. Retrieved from http://www.en.oxfordenglishdictionaries.com/definition/colonization.

Dodds, K. 2006. “Post-colonial Antarctica: An emerging engagement.” Polar Record, 42 (1): 59-70.

Harrison, Maggie. 2022. “Mars Astronauts Would Get a Horrifying Dose of Radiation, Study Finds.” The Byte, Futurism, August 14, https://futurism.com/the-byte/mars-astronauts-radiation-study [accessed August 23, 2022].

Hartmans, Avery. 2021. “Jeff Bezos predicts that people will one day be born in space and ‘visit Earth the way you visit, you know, Yellowstone National Park’.” Insider, November 12, https://www.businessinsider.com/jeff-bezos-humans-born-in-space-eventually-space-colonies-2021-11 [accessed August 23, 2022].

Mandel, Savannah. 2023. “Scientific colonialism from Outer Space to the American Tropics: A Commentary on Research Stations.” Technology and Culture. (Forthcoming)

Dunbar, Brian. “NASA Artemis.” NASA, https://www.nasa.gov/specials/artemis/

O’Reilly, Jessica. 2017. The Technocratic Antarctic: An Ethnography of Scientific Expertise and Environmental Governance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Ongweso, Edward. 2022. “Mars Is ‘Irrelevant to Us’ If Earth Is Doomed, Author of Legendary Mars Trilogy Says.” Vice, August 12, https://www.vice.com/en/article/ake3k5/mars-is-irrelevant-to-us-if-earth-is-doomed-author-of-legendary-mars-trilogy-says [accessed August 23, 2022].

Planetary Science Communications Team. “Europa.” NASA. Updated November 4, 2021. https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/europa/in-depth/.

Raby, Megan. 2017. American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Robinson, Kim Stanley. 2012. 2312. London: Orbit.

Robinson, Kim Stanley. 2020. Ministry for the Future. London: Orbit.

Smith, Kelly, et al. 2019. “The Great Colonization Debate.” Futures.

Wells-Jensen, Sheri. 2018. “The Case for Disabled Astronauts.” Scientific American. March 30, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-case-for-disabled-astronauts/.

Zevallos, Zuleyka. 2015. “Rethinking the Narrative of Mars Colonisation.” The Other Sociologist, March 26, https://othersociologist.com/2015/03/26/rethinking-the-narrative-of-mars-colonisation/.