Retaining a youthful appearance is a laborious and painful exercise, often rife with invisible labor. Digital beauty tech has made it much easier. Rather than altering our own faces through cosmetic procedures, we now have a conduit — an online persona — that can easily be touched up with the help of beauty editing apps or filters. This has done little to challenge ageist prejudices but has offered an avenue out of old age in the form of customization. In offering up this tech, the beauty industry can be seen to perform a bait-and-switch, displacing the weight of beauty standards from physical appearance onto our consumer choices.

As beautifying tech has become more sophisticated, accusations of catfishing have proliferated. Consider, for instance, the Chinese vlogger Qiao Biluo. Livestreaming on the platform Douyu[1], she cultivated a dedicated and predominantly-male fanbase of over 100,000 followers, who listened to her “sweet and healing voice” and watched her game. When recording, she appeared as a young woman — with large eyes, a small nose, and shiny hair — usually situated in a chair against a vibrant background. However, in 2019, this image of Biluo was abruptly undermined when her beauty filter glitched while she was streaming, revealing her to be a middle-aged woman.

The response to this glitch was harsh and instantaneous. The story ballooned internationally and the clip of her revealed appearance went viral. Bilou had inadvertently tapped into a misogynistic moral panic that crossed platforms and sought to challenge “deceitful” influencers who fake their good looks, “duping” unassuming men. People were shocked at the effectiveness of the filter but were also outraged by the way she used it — soliciting donations from her viewers, who were assured that they would see the “real her’ once she received 100,000 yuan. When they finally did see her, she was quickly condemned as disingenuous; her dulcet voice rendered a mere distraction and her appearance a complete lie. Her streaming career abruptly ended, and pending donations from her followers were canceled.

Seemingly, Bilou had made a two-fold error: she had not only failed at retaining the veneer of youth but had also subverted the expectations of how older women should behave. In other words, her critics believed that she had failed in the role of “older lady” — characterized by homeliness and composure — and had misappropriated girlish qualities instead: sweetness, prettiness, innocence, and so on. But who can blame her?

The Mask of Aging

It could be argued that in altering her appearance, Bilou was merely escaping the societal prejudices around aging. In many respects, these stifling assumptions on how she should self-present function as a metaphorical filter, constraining her desire.

Mike Featherstone and Mike Hepworth make a similar point when discussing “the mask of aging” (1991). They argue that as people get older, they often experience a gulf developed between their internal world and how they are perceived. Age comes to function as a mask, which possesses both a concealing function — stripping people of their individuality — but also a framing function in limiting the roles elderly people can occupy. What underpins their metaphor is an understanding of aging as a form of mediation: an aesthetic filter — cynically defined by wrinkling skin, drooping features, and sunspots — as well as a filter of understanding.

Their work builds on a Marxist tradition which understands “masking” as a means by which people calibrate themselves to societal expectations. This is seen in race relations, where — as Franz Fanon argues — black individuals adopt certain behaviors that make them more amenable to white expectations. Likewise, it is also a theory that has been applied in the mental health context to connote the hiding of certain feelings or actions for the sake of social ease. In other words, the wearing of these masks necessitates a performance which often undermines a person’s authenticity. If we now reflect on filters, we can understand them as materially more lightweight and customizable. They are the tech industry’s rejoinder to the “mask of aging”; ideally, they are meant to provide a way out of this performance by unlocking the potential for a more fluid identity.

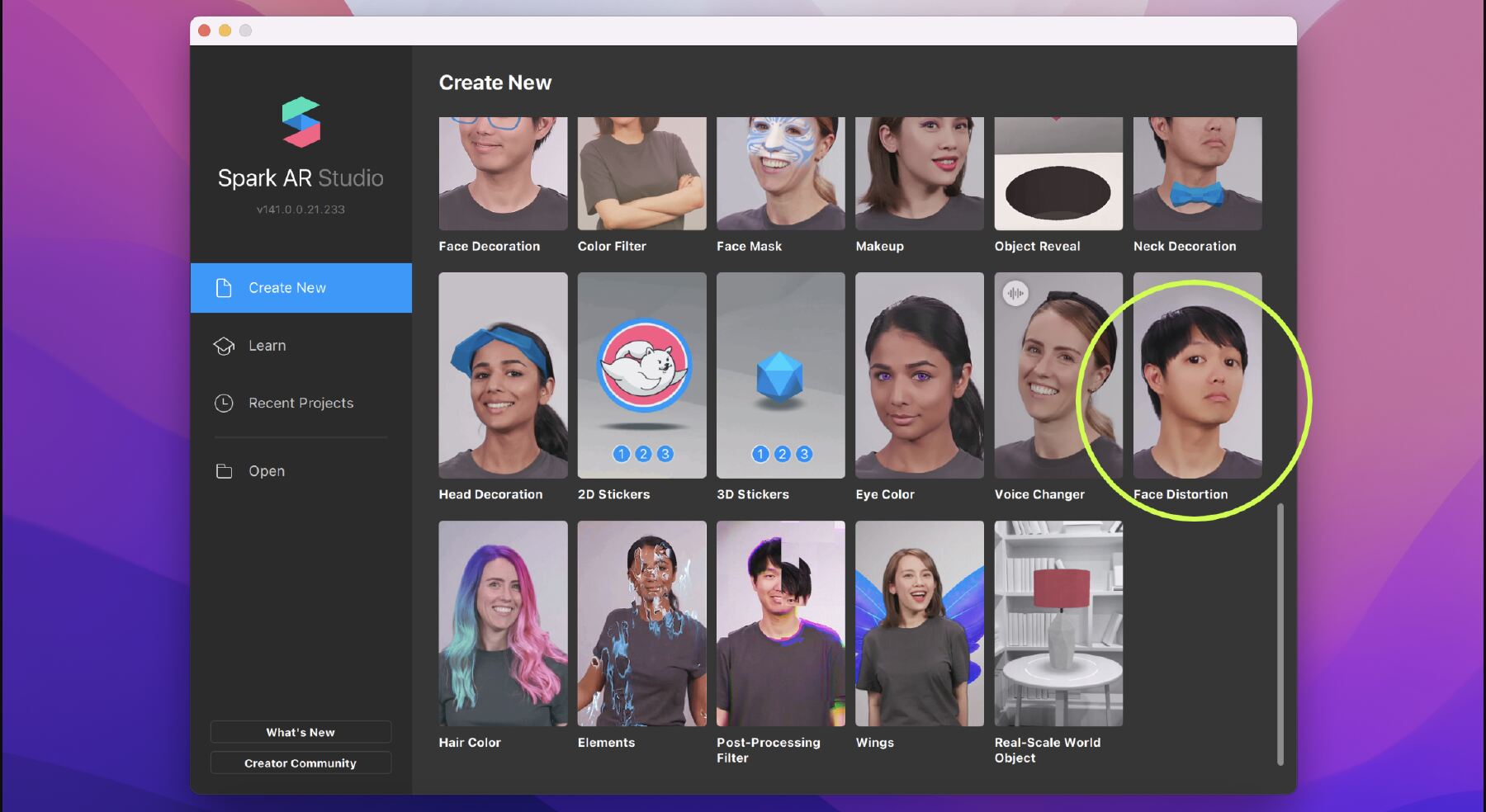

Making an Instagram filter in Spark AR Studio (image from Trusted Reviews)

To understand aging as already a mask or a “filter” has implications for how we understand the sorts of augmentations we encounter daily on social media. While it is often said that social media is a means of becoming less authentic — less like ourselves and more like everyone else — the opposite might in fact be true. When we have more control over our self-presentation, we have greater control of how we are perceived. We subsequently have more choice in who we want to be.

Making up the “Young Girl”

Irrespective of gender, beauty filters attempt to feminize a person’s face and make it look younger. They thereby play into a tradition of advertising that understands young women as a consumerist ideal, and thereby a suitable stand-in for every commercialized subject. Joanna Walsh, in her recent book, Girl Online: A User’s Manual, explains how on the consumer-oriented side of the internet the image of the young girl is “an avatar for everyone” (2022). This is to say that offline users are multifaceted people with nuanced lives, but online they are often conforming to the same ideal — whether that be “hot girls,” “clean girls,” or even “that girl.”

Her work builds on a cottage industry of academics that explores the exploited image of the young girl, such as Ann K. Clark who describes The Young Girl as the “historical law of all pleasure” (1987), and Tiqqun (a French collective of authors and activists) as the “model citizen as redefined by consumer society.”[2] The qualities young women are attributed in these commercial contexts are largely anodyne; their care-freeness means that they can be seen doing anything; their naivety means that they could desire anything; and their pureness means that they are never diminished by their consumer choices.

In consuming our way to youth, users are making a twofold error: they are stoking the very culture that makes them feel “masked” in the first place; while also adopting a “universal” image to feel more like themselves. This fails because beauty standards hinge on the elevation of a select few over the many. In this sense, when everyone aspires to the same look, it merely intensifies the competition or judgment between those who successfully achieve it and those who don’t.

Yet, the image of youth online is proven to be simultaneously too static and too ephemeral to be easily copied. The notion of the “young girl” retains a certain consistency, yet what defines her is subject to shifting consumer preferences. Certain attributes remain unchanging — her thinness, her whiteness, and her purchasing power — which most users cannot emulate, as she represents a toxic yet idealized minority. At the same time, her youthful appeal is not just a reflection of her appearance but also the relevance of the products she promotes.

In order to retain her relevance, “the young girl” is forced — in accordance with market interests — to shed the old in exchange for the new, as not to be dated by that which surrounds her, from brands to specific products. Filters function in a similar way. They are constantly being refreshed, and as long as the user stays on top of their trends, they can “become” — again, in a very limited way — the ideal commercial subject implied by this month’s idealized young girl. But that requires staying on top of the trends.

A disconcerting feedback loop develops, where platforms push filters that look like celebrities; celebrities perpetuate online trends; brands develop products simulating these trends (Revolution’s IRL Filter Longwear Foundation, for example); and the products are eventually marketed back through more filters. Each fad quickly expires. When it does, it comes to function as a tripwire upon which less aware users stumble — consequently revealing their age. Such microtrends promise endless youth while undermining it with their own disposability.

The Dated Filter

While anti-aging tech can remove the features of aging from our appearance, it mostly just displaces them onto our technological preferences. In other words, what marks one as “old” becomes a matter of the choice of technology one chooses to look young. It is exposed in the phone one uses, the platforms they gravitate to, and the aesthetics they adopt. Beneath this faux-democratization is the same reality: youth is a hegemonic culture that is largely reserved for those who are young in age.

The irony of pursuing youth is that the mechanisms employed to stay “young” tend to be easily identified as such. That, or they are self-defeating in their ephemerality: they rely too heavily on the fashions popular at the time of their production. So when people use technology as a way out of ageism, they aren’t confronting the stigmas or aging so much as putting it onto the commodities that surround them, whether that be their phone or apps.

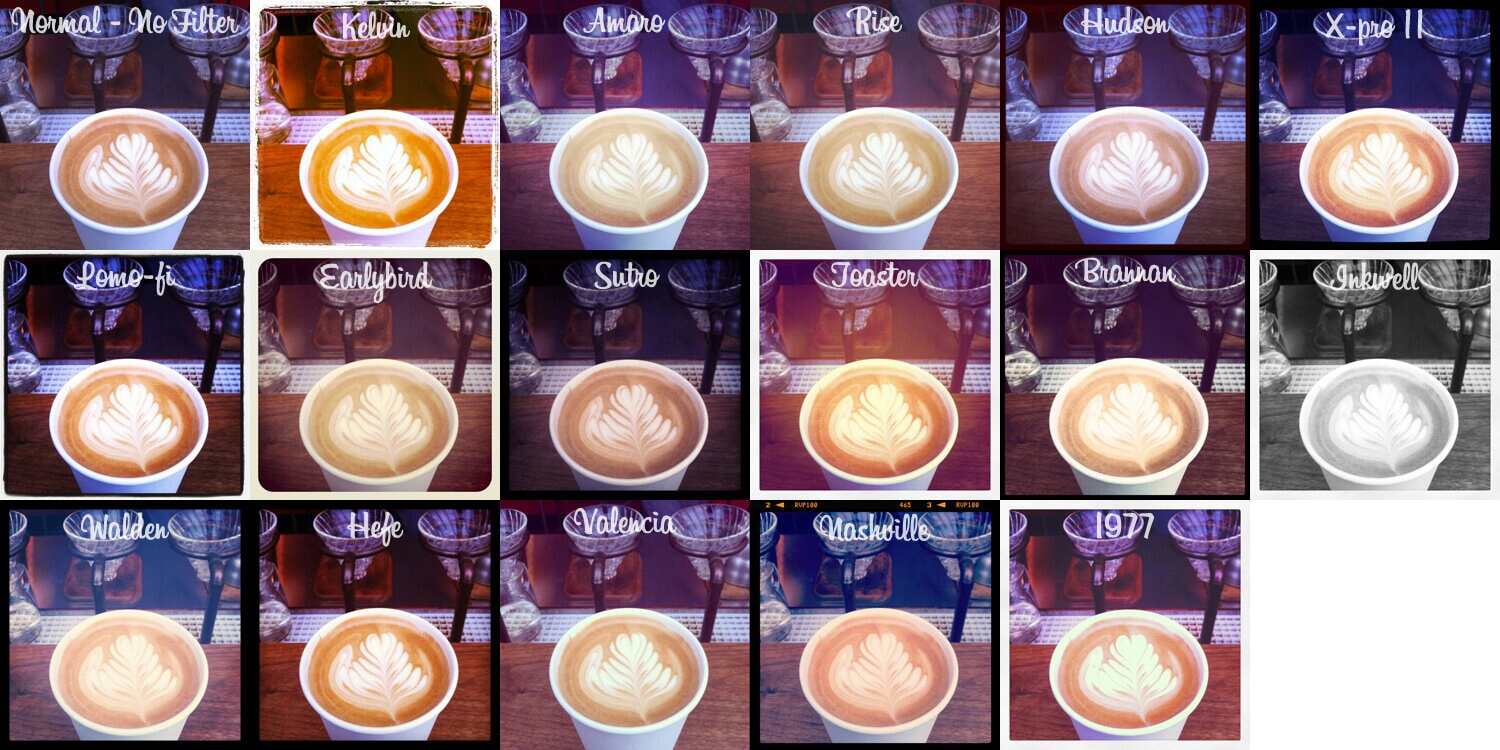

Original Instagram filters like “Gotham” and “Nashville” now seem hopelessly of their time. The same can be said of the subject matters they once framed. Autumnal pictures of lattes and landscapes are “cheugy”[3] — as, perhaps, is the term “cheugy” — as well as the overly sincere captions that accompanied them (“But first, coffee”). Inevitably the same fate awaits the current cohort of fads: TikTok stars will age, dances will go out of style, and youth will gravitate towards a new app, or a new phone. Technology ages, just as we do. Like the “young girl,” however, it retains a profitable association with the always-new.

Instagram filters on a cup of coffee (image from Wikimedia Commons)

The reality is that people now age with technology. We see this when old tech becomes visible online — in viral videos of kids reacting to defunct tech and floppy disk memes, which evoke nostalgia and allow users to laugh at their age. But we also see it in the disappearance of obsolete tech that has been phased out, mirroring the disposability that many older people experience. These similarities are not merely coincidental: tech is a determinant of users’ age, and vice-versa. Anti-aging technology fails because it faces the same prejudices that users do. Beauty filters designed to reverse the signs of aging inevitably date themselves through their design. Worse still, they tend to perpetuate the issues they are trying to remedy. As users try to pursue youth via tech it is clear that it is more elusive than ever; the more users collectively chase it, the further it remains out of reach.

Notes

[1] Douyu is one of China’s most popular live-streaming websites, where people can share everything from video gaming to make-up tutorials. It functions much like Twitch.

[2] For further discussion, see: Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2012

[3] Cheugy is a pejorative description of lifestyle trends associated with the early 2010s and millennials.

Bibliography

Clark, Ann. “The Girl: A Rhetoric of Desire.” Cultural Studies 1, no. 2 (1987): 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502388700490141.

Featherstone, Mike, and Mike Hepworth. “The Mask of Ageing and the Postmodern Life Course.” The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory, 1991, 371–89. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280546.n15.

Walsh, Joanna. Girl Online: A User Manual. London: Verso, 2022.