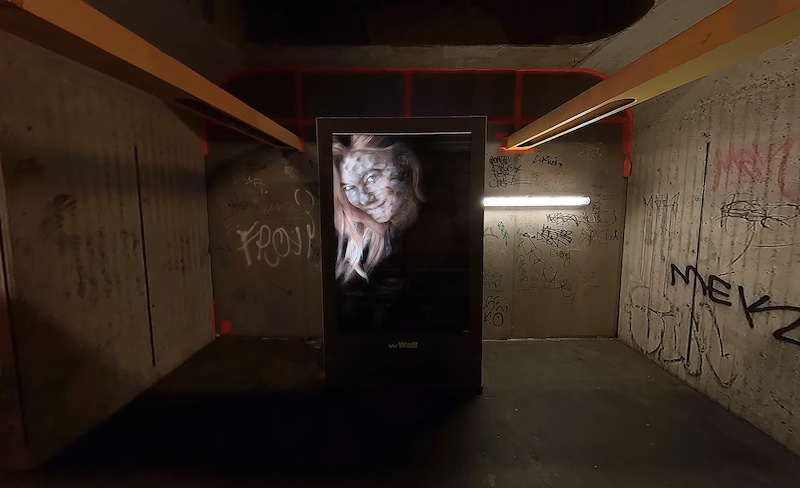

I’m standing on the train platform of U Schloßstraße, an U-Bahn station in Berlin’s Steglitz neighborhood. In front of me is an artwork: a beauty advertisement depicting a smiling woman. The model’s image has been altered with chemical solvents, giving her skin a brushwork-like texture and her complexion a ghostly paleness. I observe the dark, graffitied station around me. The arrivals board says the time is 5:20, but I’m unsure whether it’s early morning or evening. Commuters are wearing winter jackets and KN95 masks. Some read books as they wait for the train. Four young men play a game of tag. I hear the hum of an incoming U9 train and watch its arrival soon after. The doors open and the announcement blasts: Zurückbleiben bitte. Passengers leave the yellow train cars before new ones enter. After a beep, the doors close and the train hums away. The platform empties, leaving only the model’s altered image in my company. Pleased with the experience, I remove the VR goggles and return to a pop-up art gallery on Kurfürstemdamm, Berlin’s famous shopping street. This VR artwork, part of the Immersion series by the artist Vermibus, is now preserved on the Ethereum blockchain as an NFT. It was purchased for 2.4 ETH by Lango1 and remains tied to that user’s Ethereum wallet. Lango1 now owns a singular, authorized copy of the artwork—and with it, a Berlin moment whose physical version has been lost to time.

A still from “Immersion (U Schloßstraße)” by Vermibus, 2022 (screenshot by author).

Since the crypto market’s surge in 2020, an active community of blockchain and NFT enthusiasts has emerged in the city. At the time, more of the city’s many artists began making NFTs hoping to “finally be able to live off of their art,” as one told me. Some of the city’s galleries were also exploring NFTs in hopes of developing the market for digital art. Beyond the city’s art scene, local entrepreneurs were building blockchain applications out of hip Kreuzberg’s new blockchain co-working spaces. Enthusiasts like these regularly gathered for weeknight meetups and events in parks, galleries, and bars across the city. Groups like NFT Club Berlin organized many of these events, seeking to make Berlin “Europe’s center for NFTs.” During the summer of 2022, I spent three months in Berlin attending these events as an ethnographer. I also met with NFT enthusiasts individually to learn more about their work. I was studying the dynamics and implications of an offline community whose core technology was virtual.

An NFT exhibition on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm (image by author).

Berlin joins cities like Los Angeles, New York, Lisbon, and London as a hub of blockchain ventures. Yet Berlin’s NFT projects, Immersion included, stand out in an important way. Projects elsewhere are typically detached from their physical places of origin, taking on a generic, if not sanitized, aesthetic. Take, for example, Meta’s Horizon Worlds—a non-place par excellence. In sharp contrast, projects launched in Berlin tend to incorporate their local origins, taking on the city’s famously gritty and countercultural ethos. Some projects even seek to build entire virtual environments in a Berlin style, creating opportunities for virtual avatars to explore, experience, and sometimes even purchase pieces of a virtual Berlin, present or past.

Berlin’s NFT projects and events remind us that the users of blockchain, like users of any digital technology, are embodied, emplaced, and encultured beings whose lives extend beyond the immediate site of technological interaction. By extension, the affordances of the technologies they use take on particular meanings and values in local context. In Berlin, one key function of NFTs, the function of authentication, becomes a means for preserving the city’s authenticity amid the perceived disappearance of its ethos.

NFTs and Authentication

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, represent unique digital objects and in theory enable their possession and exchange as commodities. As the developers of Ethereum, the first blockchain to support NFTs, describe them, “NFTs and Ethereum solve some of the problems that exist in the internet today. As everything becomes more digital, there’s a need to replicate the properties of physical items like scarcity, uniqueness, and proof of ownership.” By valorizing scarcity, uniqueness, and ownership, the Ethereum developers problematize the aspects of mechanical reproduction that Walter Benjamin (1935 [1986]) praises in his classic account of the process. According to Benjamin, art is traditionally distinguished as a singular, original object by its presence: “its unique existence at the place where it happens to be…the changes which it may have suffered in physical condition over the years as well as the various changes in its ownership” (Section II). Encountering an artwork’s presence generates its singular, authentic aura. For Benjamin, mechanical reproduction effects a “withering” of the aura because reproduction “substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence” (Section II), alienating the artwork from its original presence. Benjamin deems this transformation liberating, but for the developers of Ethereum, the aura’s erosion is problematic: it disrupts the market.

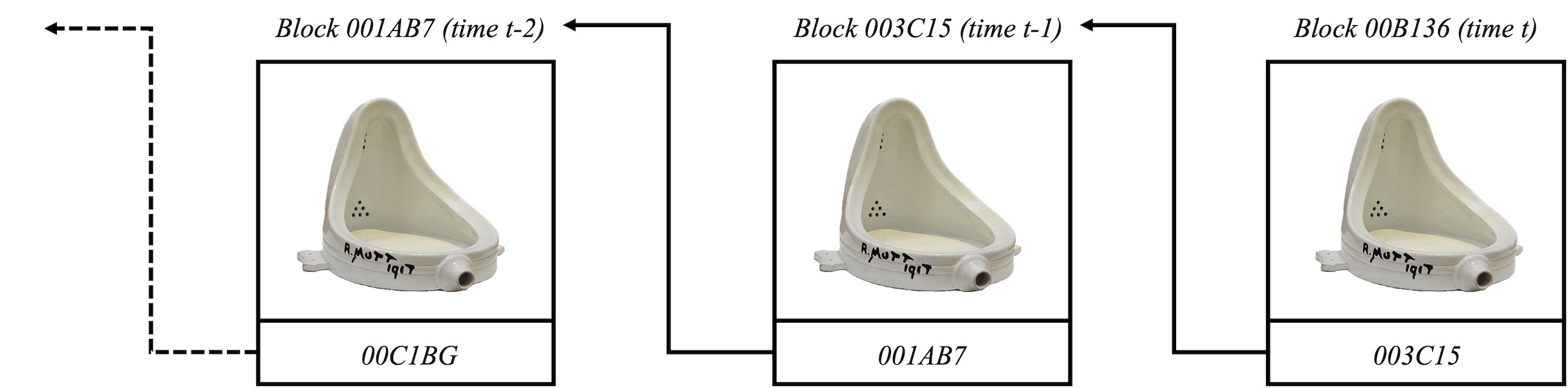

Placing NFTs in art historical context, David Joselit (2021) calls them “readymades in reverse,” referring to Marcel Duchamp’s sculptures. For Joselit, Duchamp’s readymades “gave sculpture over to information” and “abandoned objects for discourse,” in other words enabling limitless reproduction. On the other hand, Joselit writes, “the NFT has arrived to reverse Duchamp’s gesture…. The fungibility of information… has been arrested in the form of an NFT as private property” (3). NFTs reverse digital media’s tendency towards replication, reintroducing singularity and authenticity—and by extension the commodity form. NFTs achieve this effect by using blockchain as a medium for a digital object’s presence, in turn reenabling the experience of its aura. They effectively function as certificates of authenticity, but whereas traditional versions rely on institutional endorsement and their own physical presence, NFTs derive authority from blockchains’ technical properties—namely their cryptographically secured immutability. NFTs replace documents, chemical tests, x-rays, and connoisseurship with hash functions and consensus protocols as tools for distinguishing between the authentic object and its worthless reproduction.

“Blockchained Fountains” (Image by author featuring Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain”).

From Authentication to Preservation

NFTs’ authentication function figures centrally in the NFT projects I encountered in Berlin, including Immersion. The VR experience is itself an archival copy of an original artwork. Critiquing contemporary beauty standards in advertising, Vermibus removes poster ads from public space (often metro stations or bus stops), applies chemical solvents to alter brand logos and models’ faces, and returns the posters to their original locations. This physical intervention is short-lived; once identified by maintenance crews, the altered ads are replaced with copies of the original. This is where Immersion steps in: Vermibus recorded the physical work in situ using monoscopic 360-degree video to produce an immersive VR viewing experience long after the work’s removal. The video file is then minted as an NFT, creating a single authorized copy available for collection and exchange. The project states: “With the purchase of these NFTs, you’re acquiring not only the original high-resolution digital artwork files, but an indelible signature of the artist… which translates into digital proof of authenticity and uniqueness.” Long after the physical artwork vanishes, its NFT lives on—and with it, a moment in the Berlin U-Bahn.

Immersion certainly has a commercial goal: the NFTs can be purchased on OpenSea, the largest online NFT market, and proceeds go to the artist. Yet the project claims higher aspirations. The website continues: buyers of the work become “a patron for digital street art preservation.” Coupled with the monetary project, then, is one of preservation. As Vermibus told me in conversation, these projects are linked: “I wouldn’t have developed this project if [not for] NFTs. NFTs were crucial for me to explore the VR possibilities.” Vermibus leverages NFTs’ capacity for authentication towards a larger project of preservation. Importantly, the Immersion VR experience preserves not only the artwork, but also a unique Berlin moment in space and time—a moment framed by the fleeting presence of street art, a medium that is closely tied to the city’s ethos.

Numerous NFT projects in Berlin preserve the sights and ethos of the city in one way or another. This includes I’ve Never Been To, an NFT collection of digitized models of Berghain, the city’s legendary techno club housed in a former heating plant. The project describes its goal as “capturing fantasies, cliches and desires around this contemporary place of longing.” It offers collectors the chance to obtain a unique version, playfully reminding us that “Stepping into Berlin’s nightlife you never know how that night will end…”

“I’ve Never Been To” by Neopen, 2022.

In a similar move, some local collectors take cues from the urban environment and its history when designing virtual galleries to display their acquisitions. One such collector built The Factory, styled after an imagined steel plant. According to its description, the factory sits “on the outskirts of Berlin… dormant for the last 37 years.”

The Factory by Oyacaro (screenshot by author).

Immersion’s VR U-Bahn station, I’ve Never Been To’s copy of Berghain, and The Factory’s imagined steel plant all evoke the so-called “voids of Berlin” described by Germanist Andreas Huyssen (1997), referring to the empty urban spaces cleared by war and division during the 20th century. Berlin’s voids opened in the wake of American and British bombers, the Sanierung (urban renewal) projects of the 1950s, and, of course, the construction of the Berlin wall and its surrounding “Death Zone.” These voids, however, did not remain empty after Unification. Rather, they incubated the city’s now famous countercultural scenes. As Katrina Sark describes of the so-called “Babylon Berlin” of the 90s, this was “a time of seemingly limitless possibility, mobility, and creativity, when property ownership was unclear and public authorities didn’t yet work properly” (2019, 32). By the new millennium, this environment disappeared, leaving an intense nostalgia amid development projects like Potsdammer Platz, a rising cost of living, and the controversial arrival of multinational tech companies like Google. Much of Berlin’s NFT projects reflect this nostalgic sensibility, seeking to preserve their city’s voids in virtual form as their physical versions disappear.

Of course, these preservation projects also emerge from the very dynamics driving much of the city’s current transformation. In this way, they evoke a passage in Baudrillard’s (1972) Simulacra and Simulation:

Science and technology were recently mobilized to save the mummy of Ramses II, after it was left to rot for several dozen years in the depths of a museum… [but] mummies don’t rot from worms: they die from being transplanted from a slow order of the symbolic, master over putrefaction and death, to an order of history, science, and museums, our order. (11)

To this order we can add the market, and the market has not been kind to Berlin’s Web3 projects. Few of the pieces in Vermibus’ Immersion collection have actually sold. The same can be said for I’ve Never Been To. These projects all emerged during the onset of the so-called “Crypto Winter,” a crash in the cryptocurrency and NFT markets beginning in May 2022 and still ongoing. Given the crash, the limited sales are not surprising. These projects’ ability to create an archive of the city depends on their ability to generate revenue through NFT sales, and their performance reveals the limits of using market-oriented technologies towards locally meaningful, non-market ends. After more than a year, the Crypto Winter shows no signs of thawing. At this rate, the unique slices and simulations of Berlin may disappear with time, just like their physical originals.

References

Baudrillard, Jean. 1972. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign.Benjamin, Walter. 1986. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 217–52. New York: Schocken Books.Huyssen, Andreas. 1997. “The Voids of Berlin.” Critical Inquiry 24 (1): 57–81.Joselit, David. 2021. “NFTs, or The Readymade Reversed.” October, no. 175 (April): 3–4.Sark, Katrina. 2019. “Cultural History of Post-Wall Berlin: From Utopian Longing to Nostalgia for Babylon.” In Cultural Topographies of the New Berlin, edited by Karin Bauer and Jennifer Ruth Hosek, 25–52. New York: Berghahn Books.