A Swindle Exposed

1913, Chicago: A reporter, assuming the name Edward Donlin, enters a downtown medical establishment that has advertised widely in Midwestern newspapers offering Dr. Paul Ehrlich’s new miraculous cure for ‘blood poison’—syphilis—for a price. ‘Donlin’ pays $2 in fees, then the consultation begins. He feigns concern about recent hair loss, and the doctor (who, matching the picture in advertisements, wears a Van Dyke beard) laughs strangely then turns grave: it is certainly syphilis. He recommends a Wassermann test, a recently-invented syphilis diagnostic, for $20 and Ehrlich’s Salvarsan for $30. Pleading financial difficulty, the reporter holds him off with a $2 down-payment and departs.

The Chicago Tribune exposed the bearded doctor alongside several other ‘quacks’ in its October 27 and October 29 issues (Chicago Daily Tribune 1913a, Chicago Daily Tribune 1913b).[1] The doctor, who in advertisements represented himself ambiguously as Ehrlich himself, signed the receipt ‘Coburn,’ and offered the name ‘Coe,’ was actually a pair of brothers who each maintained a private practice and together “are known as reputable and ethical practicing family physicians. They are: Dr. W. A. Code, 202 South Kedzie Avenue… [and] Dr. W. E. Code, office 2 West Chicago Avenue.”[2] In defense, Walter Code claimed that it was ‘Donlin’ who deceived him; he would have been more vigilant if he were “one of these fakes who advertise cures for anything.”[3]

Code’s ambiguous identity and exaggerated affect during the reported consultation, his inflated prices (compare to Salvarsan’s regular selling price of $3.50 per ampule; Ward 1981: 61), and his efforts to evade the charge of deceit paint him and his brother as consummate fakers. Yet the Codes had also maintained apparently reputable practices, William’s just a 20-minute walk across the Chicago River from their seedy Salvarsan clinic.

I found the Codes in a pamphlet for men’s specialists, preserved in the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine collection.[4] The collection builds from the prodigious files of London-born physician Arthur J. Cramp, who dedicated his career with the AMA to exposing medical frauds. He spearheaded the Propaganda for Reform Department, debunking the exaggerated claims of patent medicine purveyors in the AMA’s flagship journal. Unlike patent medicines like “Dr. J. Lawrence Hill’s Rational $10 Three-Fold Treatment for Consumption, Asthma, Bronchitis, Catarrh and all Diseases of the Throat, Nose and Lungs” (Propaganda for Reform 1911), however, Salvarsan was a brand name that, from its global debut in 1910, had been widely acclaimed as a powerful, novel cure for syphilis.

Cramp followed news about Salvarsan with some concern, fielding inquiries about ‘606’ advertisements from doctors, clipping newspaper stories, and corresponding with regulatory authorities. But he was stymied by contradictions—reputable doctors operating quack establishments; profiteering fakers selling the real thing—that seem now to reverberate with Salvarsan’s faded promise as the first ‘magic bullet.’ How might Cramp’s preoccupation with Salvarsan fakery help us to understand the American medical marketplace during an era of change, of the medical profession itself as well as its means of treatment?

The Promise of Salvarsan

On April 9, 1910, German chemist Paul Ehrlich announced his discovery, with Japanese bacteriologist Sahachirō Hata, of an arsenic compound (the 606th tested) with specific action against syphilis spirochetes at the Congress of Internal Medicine at Wiesbaden. Chicago physician B. C. Corbus, propounding ‘The Value of Ehrlich’s New Discovery ‘606’” in the October 22, 1910 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), observed that 606 was a new kind of ‘specific’: neither was it a single chemical like mercury, the specific of “olden times” that physicians still used to treat syphilis, nor did it target a specific disease through the formation of antibodies, as in immunotherapies like vaccines or diphtheria antitoxin (Corbus 1910). Rather, Ehrlich’s new chemotherapy promised to deliver powerful poison to pathogenic spirochetes while sparing bodily tissues.

The New York Times, paraphrasing Samuel J. Meltzer of the Rockefeller Medical Institute, called the discovery “epoch-making.”[5] American physicians Henry J. Nichols and John A. Fordyce described 606’s remarkable effects on 14 hospitalized syphilis patients in the October 1, 1910 issue of JAMA. “The final word concerning its value will not of course be said for a number of years,” they wrote, “but the fact remains that we possess no other drug the extraordinary effects of which in syphilis equals that of ‘606’” (Nichols and Fordyce 1910).

A JAMA editorial published February 11, 1911, titled “Need of Caution in the Use of Salvarsan,” identified two threatening ‘evils’ lurking amidst the widespread enthusiasm:

“One is the unwarranted optimism aroused by the claims made by over-enthusiastic advocates. This evil is corrected by time, added experience and critical investigation, and while it often leads to disappointment, it is apparently unavoidable. The second and far more dangerous evil is the exploitation of the new discovery by the faker and the quack who are quick to seize the golden opportunity offered and to use the public interest for their own selfish advantage.”[6]

As 606 became more widely available, clinical experience did much to dampen ‘unwarranted optimism.’ Some physicians openly doubted Salvarsan’s superiority to the traditional mercury treatments; mounting fatalities led Ehrlich to advocate exclusively for difficult surgical intravenous injections and closer attention to contraindications; reports of syphilis recurrence eroded the promise of a single-dose cure (Ward 1910). The AMA’s attention to the second, ‘far more dangerous evil,’ though, indicates that not only therapeutic novelty was at stake. The science behind Ehrlich’s discovery notwithstanding, Salvarsan’s promise to miraculously eradicate a disease shrouded in shame and secrecy recalled, at least to AMA leaders, the exaggerated claims of patent medicines and advertising healers. What kind of a commodity would Salvarsan become?

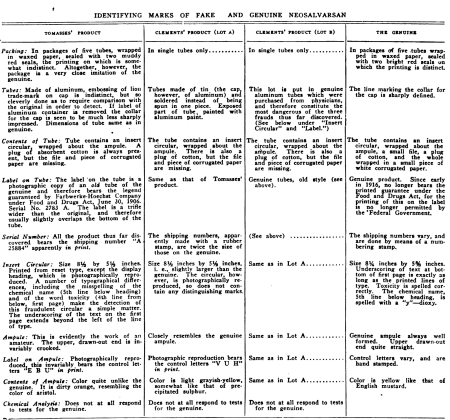

A table instructing doctors on how to detect vials of fake Neosalvarsan, published in JAMA. “Identifying Fake Neosalvarsan,” Journal of the American Medical Association 69 (1917): 1021. (Open access via HathiTrust)

Therapeutic Commodities on the Medical Market

Arjun Appadurai has called upon anthropologists to track things through contexts of exchange in order to analyze the materially-situated regimes of value they traverse (Appadurai 1986). The documents collected in the AMA archives trace Salvarsan’s itineraries through the American medical marketplace of the 1910s—through clinics and hospitals, mail-order forms, and even speculative markets—even as the policies, practices, and knowledges that determined its therapeutic and economic value changed. In particular, the AMA Salvarsan archive preserves Cramp’s rigorous pursuit of distinctions between legitimate and illegitimate transactions and uses of Salvarsan.

Historian Roy Porter distinguished ‘quacks’ from ‘regulars’ in early modern England not on the grounds of truth and falsity, but rather economic strategy. How, amidst emerging capitalist conditions, did people attempt to make money by treating disease? Regulars, he argued, built up steady practices through personal connections; quacks advertised standardized commodities to anonymous consumers (Porter 1989). Salvarsan debuted on the American market amidst intense struggles over the economics of medical practice. The AMA battled with patent medicine manufacturers—many of whom drew business from regular physicians as well as home medicators—over the very nature of the medical marketplace (Tomes 2016; Caplan 1989). Who could claim medical expertise? Should healers be allowed to advertise? What cures should laypeople be able to purchase for themselves?

In the case of Salvarsan, the complex interplay of fakery and reality, which Cramp sought to discipline into clearly bounded regimes of (il)legitimacy, was in fact dictated by complex pattens of production and distribution, advertising and demand, and epistemic and therapeutic authority. One early case throws several of these patterns into sharp relief.

Remote Doctors in 1911

In order to control the quality and distribution of his syphilis cure, Ehrlich patented 606, and the German chemical firm Farbwerke-Hoechst gained sole manufacturing rights. In early 1911, soon after Salvarsan hit the American market, Cramp became aware of a New York City outfit called ‘606 Laboratories,’ which advertised Salvarsan directly to patients for $30 a dose. 606 Laboratories adapted cannily to the emerging therapeutic consensus that Salvarsan should be injected intravenously (rather than simply hypodermically) by a trained physician. Customers would receive a dose of Salvarsan via mail, with a full set of instructions for its administration; as one form letter in Cramp’s file reads, “Any doctor can administer it easily.”[7] 606 Laboratories’ director, James Haze Scott,[8] also sent local doctors form letters proposing a business deal: 606 Laboratories would pay the doctor $5 per injection—billed directly—to travel to customers’ residences and inject the Salvarsan they had ordered. Cramp preserved a letter sent to St. Louis physician Dr. J. N. Frank, dated June 24, 1911, in which Scott sweetened the deal: “It has been our experience that the physicians throughout this country who do this work average about $40 per patient on additional fees secured for necessary tonic treatment, further injections, blood tests, and whatever else in their discretion they deem necessary … We assist the physician in getting this money by inducing the patient by letter to continue treatment with the physician and in this way a good practice can be built up among these people.”[9]

Doctors and newspaper editors wrote to Cramp about 606 Laboratories advertisements, in tones ranging from skepticism to outrage. As early as February 1911, however, Cramp’s own indignance was tinged with resignation. To Frederick Paul of the Toronto Saturday Night, Cramp admitted that “the unfortunate part of it is that these fakers, apparently, have the genuine Salvarsan for sale. We have taken the matter up with the American agents who claim that they are using every effort to prevent the product falling into the hands of quacks.”[10] In January of 1911, AMA secretary George Simmons had corresponded with Dr. Wainwright of New York City, tasked with managing Salvarsan’s American distribution. Wainwright denied that he had sold Salvarsan to any quacks (affirming his own ability to ‘smell out’ dubious cases) but cast suspicion on pharmacists, who he had advised to sell only to patients with prescriptions from reputable doctors. In a handwritten note affixed to Wainwright’s letter, Cramp writes:

“If it was a case of the quacks selling ‘606’ at ‘cut prices’ instead of at advanced prices, Wainwright would quickly enough find out who sold the product to them. The serial numbering plan by which every bottle of serum can be traced through wholesaler, jobber and retailer could very easily be applied to Salvarsan — if the American agents wanted to!”[11]

If only 606 Laboratories had attempted to undercut the Salvarsan market, Cramp lamented, authorities might finally be motivated to track individual units and uncover illicit commodity-trajectories.

Alongside reliable agents, doctors’ diagnostic authority was central to Cramp’s efforts to control Salvarsan’s itinerary through the American medical marketplace. Diagnosis not only ensured accurate and, presumably, effective administration of the powerful drug, it also differentiated legitimate Salvarsan transactions from ones suspect of fraud or profiteering. Mail-order schemes proved so problematic to Cramp because they proposed to bypass expert diagnosis. By sending Salvarsan straight to patients’ homes, 606 Laboratories reduced the doctor’s role to a purely technical one: injecting the drug. However, just as expert diagnosis ordered a series of clinical actions—each legitimating an economic transfer—Scott encouraged doctors to create opportunities for additional services, with additional fees attached. Doctors could pad their pockets and build up clientele, Scott promised, simply by requiring Wassermann tests, prescribing tonics, scheduling follow-ups.

‘Quackery,’ then, was not simply a matter of overpricing—though inflated prices certainly aroused Cramp’s concern. Nor was it just about fakery—for there was often a grain of the real. Quackery was also about a transactional model that differed from that of the ‘regular’ physician in its configuration of purchasing power and therapeutic authority.

Notes

[1] “Cure Fakers Find Disease in Well Men,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 27 October 1913: 1. “State Board Prepared to Fight Quacks,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 29 October 1913: 1.

[2] “State Board Prepared to Fight Quacks.”

[3] “State Board Prepared to Fight Quacks.”

[4] “’Professor Ehrlich’ — He Sees Syphilis in his Perfectly Healthy Caller and Wants $50 for Treatment,” 1913, Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection; Box 769, Folder 3 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Archives). Courtesy American Medical Association Archives.

[5] “Finds a Specific for Blood Diseases,” New York Times, August 3, 1910: 5.

[6] “Need of Caution in the Use of Salvarsan,” 1911, Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection; Box 769, Folder 3 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Archives). © American Medical Association, February 11, 1911. All rights reserved. / Courtesy AMA Archives.

[7] 606 Laboratories to Colman Miner, 1911, Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection; Box 769, Folder 3 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Archives). Courtesy American Medical Association Archives.

[8] Later, Scott would be replaced as director of ‘606 Laboratories’ by G. N. Bancker, himself a medical college graduate and registered physician.

[9] ‘606’ Laboratories to J. N. Frank, 1911, Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection; Box 769, Folder 4 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Archives). Courtesy American Medical Association Archives.

[10] Arthur Cramp to Frederick Paul, 1911, Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection; Box 769, Folder 4 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Archives). Courtesy American Medical Association Archives.

[11] Arthur Cramp, 1911, Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection; Box 769, Folder 4 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Archives). Courtesy American Medical Association Archives.

References

Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai, 3-63. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Caplan, Ronald. 1989. “The Commodification of American Health Care.” Social Science and Medicine 28: 1139-1148.

Corbus, B. C. “The Value of Ehrlich’s New Discovery ‘606’ (Dioxydiamidoarsenobenzol),” Journal of the American Medical Association 55 (October 22): 1470-1472.

Nichols, Henry J. and John A. Fordyce. 1910. “The Treatment of Syphilis with Ehrlich’s ‘606.’” Journal of the American Medical Association 55 (October 1): 1171-1178.

Porter, Roy. Health for Sale: Quackery in England, 1660-1850. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1989.

The Propaganda for Reform. 1911. “J. Lawrence Hill, A.M., D.D., M.D., Another Consumption Cure Fake in Jackson, Michigan,” Journal of the American Medical Association 56 (January 14): 134-137.

Tomes, Nancy. 2016. Remaking the American Patient. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Ward, Patricia Spain. 1981. “The American Reception of Salvarsan,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 36: 44-62.