“There is nothing like an iPhone …to show people the problem…”

-Alex Vitale, The End of Policing

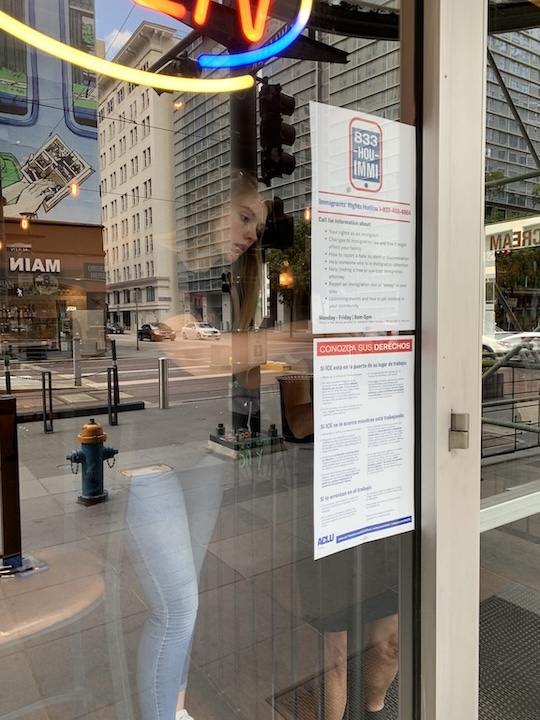

An ACLU volunteer hangs informational posters in downtown Houston. The top poster promotes the Immigrant Rights Hotline and the bottom poster informs readers of their rights when interacting with law enforcement. (Image by Author)

As I contemplate the momentum of the 2024 presidential election cycle, my focus turns to the potential consequences of a renewed Trump presidency. Drawing on my expertise as an ethnographer, I recall the socio-technological impacts of his initial presidency, which fueled activism and organizing for civil liberties. What follows is a reflection on my fieldwork in Houston, Texas during 2018 and 2019, focusing on how anti-surveillance advocates at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Texas used cell phones and their cameras as resistance tools. The ACLU has been an active proponent for those in need of protection from government surveillance by educating people in the US on their constitutional rights, advocating for the protection of civil liberties, and taking legal action to stop violations of those rights and liberties. During my eighteen months of research, I engaged with anti-surveillance advocates at the national, state, and city levels who prepared organizing efforts and legal cases limiting unlawful surveillance capabilities. For this piece, I focus on promoting cell phone camera usage in ACLU’s “Know Your Rights” workshops and through the ACLU Blue and ACLU La Migra mobile applications. Throughout the piece, I reckon with what Deborah Thomas calls “the often difficult-to-parse relationships between surveillance and witnessing” (2000, 717). Witnessing the precarity of past ethnographic junctures can highlight injustices, bring them to attention, and formulate strategies for their alleviation. Thus, bearing witness to the past moments may help gain agency over unpredictable futures.

Photography and videography have emerged as potent tools enabling the disempowered to document interactions with those in positions of authority. As articulated by bell hooks, the medium of photography holds emancipatory potential by facilitating connections across temporal and spatial boundaries (1995). This capacity for photography to serve as a conduit for resistance is particularly evident when it portrays marginalized communities, colonial subjects, or incarcerated individuals.

I explore the role of activists, organizers, and ordinary citizens in challenging the hegemony of state surveillance mechanisms by adopting a practice known as sousveillance, exemplified by the act of reversing the gaze through cellular phone cameras (Mann et al., 2003). However, the efficacy of this reciprocal surveillance is contingent upon the observer’s positionality and is therefore inherently unequal, given the underlying hierarchical power dynamics inherent in the rationale for surveillance (Ashcroft et al., 2013; Bhabha, 1994; Fanon, 1967).

“Know Your Rights” Training

Activists and organizers have realized the importance of image evidence and provide training to explain people’s right to use cameras in the face of law enforcement. I highlight the “Know Your Rights” trainings because they focus on Houston immigrant communities, particularly Black and Brown communities. People in the Houston area attend “Know Your Rights” trainings to understand their rights around law enforcement and immigration enforcement, including the right to record interactions with a camera phone. These trainings not only provide information on one’s rights, but also show how to enforce one’s rights when in law enforcement presence. I attended nine training sessions in Houston and Harris County.

An ACLU organizer, Nina, managed and facilitated the training. As a trained social worker, Nina was incredibly familiar with how to reach people who may not directly seek out ACLU resources. In her position, she proposed a project focusing on “Know Your Rights” training at religious institutions because of the trust community members placed in the organizations. Nina contacted hundreds of religious institutions in the Houston area proposing an ACLU visit. Some visits occurred as tabling among other organizations, while others were started before services as a presentation to the congregation or took place during a social hour for the congregation’s attendees. The critical facet of the initiative was Nina’s apt recognition that community members, particularly immigrant community members, placed in the organizations. Since there are numerous scams and people taking advantage of immigrant fears of law enforcement, immigrants in the US face difficulty finding organizations, places, or people to trust. Even though the ACLU is a widely known, nationwide group, immigrant people are not always aware of its repertoire and may still distrust the organization. While the ACLU works to stop the scamming of immigrants, the ACLU organizers still must prove that they are trustworthy sources. One way to gain trust is to work with a trusted religious community group.

A mosque named Masjid Al Salam in northwest Harris County was one of the religious institutions interested in the “Know Your Rights” training. Nina, an ACLU staff attorney, and two other volunteers attended the presentation before the Friday worship service. The mosque was divided into two sections, accommodating male attendees in one area and female attendees in another. Before the training began, we stood at our tables on the men’s side, distributing materials to people as they entered the worship hall. One table was staffed by ACLU volunteers and staff members, while the other was staffed by representatives from the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), a Muslim rights organization that frequently partners with the ACLU. As people entered, they were enthusiastic about the presence of the ACLU and CAIR and were interested in all the materials. It is possible that the particular interest in our presence at the mosque was because of the intense surveillance against Muslim citizens and immigrants in the United States since 9/11. For the same reasons as well as forms of isolation that some Muslim people experience in the US, mosque attendees may have a certain trust in mosques. So, the enthusiasm for the ACLU’s presence was less about us and more about the trust in the mosque institution. However, federal government agencies have abused this trust and placed spies as surveillance tools in mosques (Patel 2021, Rafei 2021). Nonetheless, visitors were pleased to see the tabling efforts and were interested in our presence. The men who entered the mosque kindly asked what the table was about, and we gave our spiel: “We are here as volunteers for the ACLU to let people know about their rights regarding law enforcement interactions. We are particularly interested in letting immigrants know that the same rights that apply to citizens also apply to immigrants regarding law enforcement interactions. In other words, everyone has the right to record the police, even if they say you cannot.”

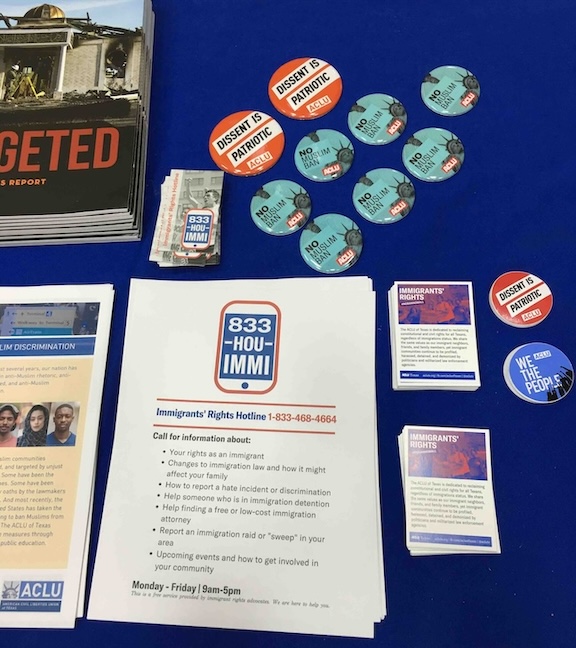

The ephemera on the table represented a complex advocacy network for immigrant rights in the United States. ACLU staff and volunteers distributed pamphlets, stickers, and pins to mosque visitors. From left to right and top to bottom, attendees could choose from a report documenting targeted Muslim persecution, a business card with the Immigrants Rights’ Hotline phone number (833-HOU-IMMI), a “Dissent is Patriotic” pin, a “No Muslim Ban” pin, an informational handout about some forms of Muslim discrimination, an entire page handout on the Immigrants Rights’ Hotline, a business card size promoting the ACLU’s fights against immigrant discrimination, and two separate stickers reading “Dissent is Patriotic” and “We the People.” (Image by Author)

The “Know Your Rights” training began with a panel of CAIR and ACLU speakers. Each speaker gave information on the organization’s work, offered information about immigrants’ fundamental rights, and answered audience questions. Although the presentations from CAIR and ACLU were not particularly focused on technology, I noticed that most of the audience asked questions about using technology in front of law enforcement, whether that was on the street, in a car pullover, or at the airport. The ACLU lawyer advised people to turn off their phones’ ability to unlock with biometrics. In 2018, a fingerprint was the more familiar way of unlocking a phone. Face recognition is now the more common biometric attached to unlocking one’s smartphone. Whichever biometric is attached to unlocking one’s phone, ACLU attorneys suggest turning biometric unlocking off when in the presence of law enforcement, whether through airport security or at a protest.

As a national organization, the ACLU has state chapters specializing in local initiatives, like the Houston-specific Immigrants’ Rights Hotline. Some local initiatives eventually become national initiatives. For example, the ACLU Blue phone application and the ACLU MigraCam phone applications were started in South Texas and are now promoted nationwide; I will turn to these topics in the next section. Throughout the training and tabling, the ACLU initiative emphasized the role of the visual in providing evidence of law enforcement treatment, whether police at a traffic stop or law enforcement at the airport.

ACLU Blue and MigraCam

In 2017, the ACLU of Texas launched a smartphone application designed to expose law enforcement misconduct and promote examples of model policing across the state. Although the application was designed and implemented by the ACLU of Texas, it is known throughout the ACLU nationally and has been promoted by state chapters. In an interview with local news, Cheryl Newcomb, the Deputy Director of the ACLU of Texas, promoted the app saying, “The ACLU Blue app will continue to record even if your phone is locked or turned off. A copy of what you recorded will automatically be uploaded to a community hub. So even if your phone is confiscated, which it should not be [since] it is legal to record police interactions, especially in public spaces, the video will still be saved and uploaded” (2017). The ACLU Blue promotion videos explain the application by saying, “Record, Share, Watch, Discuss. When you see police activity, film it.”

A MigraCam information card reading: Stream Video. Share Your Location. Know Your Rights. (Image by Author)

An organizer in South Texas saw the possibility of a similar application focused on immigration law enforcement. The application’s goal is to allow an easy recording of immigration enforcement that law enforcement cannot interfere with. Even if the police take someone’s phone, the video will be sent to their chosen contacts with their current location. If someone is picked up in an immigration raid, their last known whereabouts will be known. The swift pace of raids frequently causes panic among families and communities (Kline 2019). The ACLU La Migra app helps reduce panic by providing alerts when individuals are arrested in unannounced raids.

Users must trust that the ACLU application will not abuse access to the phone cameras, microphone, and photos. There is a certain irony in the fact that to combat law enforcement surveillance, ACLU application users must engage in forms of surveillance. Or, more accurately, in this case, forms of sousveillance.

Predicting the Future(s)

Considering the previous administration’s policies regarding immigration and civil rights, a potential return to a Trump presidency would likely exacerbate challenges faced by immigrant communities, as well as other marginalized folks. Therefore, initiatives such as “Know Your Rights” training and the promotion of technological empowerment become increasingly vital. Furthermore, the emergence of smartphone applications such as ACLU Blue and MigraCam highlights the significance of visual evidence in addressing systemic racism and instances of police violence. During periods of significant social transformation, the act of bearing witness becomes crucial in advancing collective understanding and fostering police accountability.

References

Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. 2013 [1998]. Post-colonial Studies. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Fanon, Frantz. 1967 [1952]. “The Fact of Blackness.” Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Press.

hooks, bell. 1995. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York, NY: The New Press.

Kline, Nolan. 2019. Pathogenic Policing: Immigration Enforcement and Health in the US South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Mann, Steve, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman. 2003. “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments.” Surveillance & Society 1 (3): 331-355. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v1i3.3344.

Patel, Faiza. 2021. “The Costs of 9/11’s Suspicionless Surveillance: Suppressing Communities of Color and Political Dissent.” Brennan Center for Justice, September 8. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/costs-911s-suspicionless-surveillance-suppressing-communities-color-and.

Rafei, Leila. 2021. “How the FBI Spied on Orange County Muslims And Attempted to Get Away With It.” American Civil Liberties Union, November 8. https://www.aclu.org/news/national-security/how-the-fbi-spied-on-orange-county-muslims-and-attempted-to-get-away-with-it.

Thomas, Deborah A. 2020. “Witnessing.” American Anthropologist 122 (4): 717–20.

https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13487.

Vitale, Alex S. 2017. The End of Policing. London; New York: Verso Press.