Common sense tells us that play and work are opposing categories. However, in our society we often encounter situations where the boundaries between these two categories become difficult to distinguish. It’s common that people earn money from hobbies—activities not typically associated with the effort required for any form of work, mostly because they are fun. These include recording oneself dancing on the street, doing product unboxings, or streaming while playing video games. The variety of activities that can now be monetized is vast; almost any activity can become a niche ready to be used by the market to maintain a consumerist dynamic.

Narasiah (1997) notes that working traditionally implies being employed in a defined and stable occupational role, with standardized duties, pay rates, and promotions, which provides individuals with a sense of identity and security. We can also think of it as a set of tasks and responsibilities carried out in exchange for compensation (Belbin, 2000). However, today that notion is changing due to the rise of temporary jobs, self-employment, and flexible working conditions, making it harder to distinguish traditional work. Scholars who study how people work have noted that all “productive” activities inherently possess a playful dimension at some point (Abramis, 1990; Petelczyc et al., 2018; Pargman & Svensson, 2019). When a person shows interest in earning money by playing video games, it is inevitable to wonder: If everything can potentially be considered work or professionalized, how can we define what distinguishes play?

The experiences of amateur and semi-professional digital athletes in Mexico led me to notice that play is simultaneously linked to productivity and sportsmanship. This presents a series of analytical challenges that cannot be resolved in the abstract but must be understood by considering the conditions and contexts in which play occurs. Observing the specific circumstances of the players allows us to understand how a notion of value is constructed, which often goes beyond the economic perspective. This also helps us see why play is valuable to people, often because of the joy it brings in and of itself.

One of the central concerns during my fieldwork in Mexico with gamers who aspired to become digital athletes was the paradox of work/play. These were young individuals who, in essence, sought to enter the workforce through gaming. No Mexican parent is likely to feel at ease when they hear that their child wants to earn a living as a gamer. For them, this means wasting time playing in front of a screen, nervously pressing buttons, and represents a break in the traditional Mexican narrative of social mobility. One of my interlocutors explained that their parents would repeat the idea that “you study to get a degree, to become someone in life, and secure a stable job.” However, many of my interlocutors were aware that this narrative is now outdated. This situation highlights that the future perceived by many of the young people I accompanied during my fieldwork is bleak. None of my interlocutors wanted, for example, a regular office job in the future. The idea of a routine or dedicating a lot of time to studying subjects to get a university degree did not appeal to them.

Many thinkers have emphasized the importance of placing play and enjoyment at the center of human experience, questioning the importance of work in daily life (Graeber, 2018; Lemus, 2008; Black, 2013; Ellul, 1980; Lafargue, 1977; Frayne, 2017). Perhaps this means we are at a good moment to strengthen this critical stance toward productive life, its mandate to colonize free time, and—most importantly—playtime. At the same time, it forces us to question why it seems acceptable to earn money by doing something that originally brings joy and/or pleasure, such as playing.

After accompanying various amateur and semi-professional teams of Mexican digital athletes, it became clear to me that their trajectories—like those of anyone else—are difficult to predict. This is nothing new. However, upon reviewing my field notes, I discovered that these trajectories are not as disparate, eccentric, or dissimilar as they might seem. In fact, they share some elements that can be systematized. For this reason, I began to wonder if there was an image that could represent this peculiar situation.

At first, I imagined a simple pendulum oscillating between play and work—a simple and concise way to visualize the players’ trajectories with both dimensions and how they intermingle during their training. However, this metaphor gives the impression that the players’ trajectories are predictable.

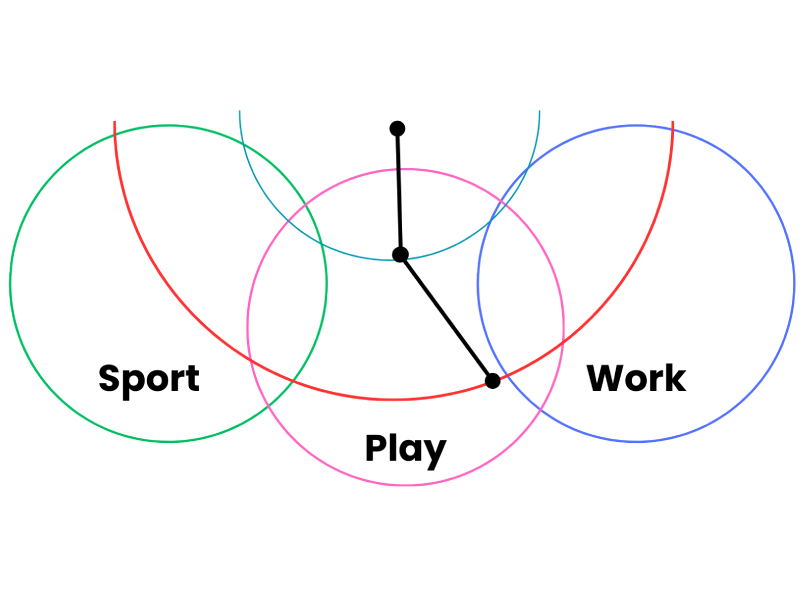

Instead, it seems more appropriate to imagine the relationship players establish with play, sports, and work as the oscillation of a double pendulum moving between three circles, each corresponding to one of these dimensions (Illustration 1). I am interested in highlighting its chaotic dynamics because they more accurately reflect the vast range of possibilities and paths contained in the players’ practices, which in turn reflect particular meanings and beliefs during play. This continuous and unpredictable movement occurs in circumstances that depend on each player’s concerns. I came across players who emphasized improving their technique through training, others whose main goal is to make money, and others who prioritized having fun above all else.

The order and size of the circles can also vary depending on the interests and conditions of each player, and this should be analyzed on a case-by-case basis. Each game requires a specific theoretical and methodological framework to be studied. However, I believe this model allows us to identify common elements in other games and forms of play. Chaotic oscillation enables us to perceive the continuous connection between the three domains, making it evident why we have analytical difficulties in marking the boundaries between playing, working, or training.

Representation of a double pendulum that chaotically oscillates through three interconnected spheres, author’s design. To see a simulation of the chaotic dynamics of the double pendulum: https://simufisica.com/es/pendulo-doble/. Image by Author.

In the case of digital athletes who aspire to earn money by playing, this idea is subversive because, from an adult perspective, it is hard to make a professional career out of play. We can imagine a pendulum model where the circle dedicated to play is larger than the other two. On the other hand, for players who get paid to level-up other people’s accounts, the subversion takes on other nuances, especially because they earn money by cheating. Setting aside the ethical and legal considerations, this suggests imagining a pendulum where the work circle is larger, as there is a contractual situation and a monetary exchange.

When video games turn into sports, two dimensions often captivate players. First, competing in tournaments is important because it allows them to gain symbolic recognition as the best in a region or, eventually, in the world. It also often means being hired by a team, securing sponsorships from companies—almost always related to digital technologies—and becoming public figures who eventually take on leadership roles within the gaming community.

Second, this transformation involves starting a much deeper learning curve that allows them to improve their physical technique—from how to sit, maintaining a healthy diet, to enhancing their reflexes when clicking the mouse. They also acquire deep knowledge of characters, team compositions, offense and defense strategies, the reading and interpretation of their own performance statistics, and a more detailed understanding of how the computers they use function, even modifying them to improve their performance.

I found it important to highlight this point because it allows us to observe the ties digital athletes can form with a sports industry that seems to be in constant growth and development. Moreover, it helps us understand the connection between the circles in the double pendulum metaphor.

We seem to live in a world where the enjoyment of life is subordinated to personal cultivation for the job market, where we engage in activities that foster employability (Frayne, 2017). In this scenario, the chaotic oscillation implies that a mechanism of the colonization of play as a productive activity has been set in motion. Thus, the practices, meanings, beliefs, and professional trajectories, while dependent on certain contextual conditions, are to a certain extent unpredictable in how they form, sustain, and conclude. For this reason, it is difficult to understand why a player might choose to play on someone else’s account and get paid for it, become a professional digital athlete and take on the responsibility of being a recognized public figure, or simply abandon everything to pursue something else.

The last possibility is to imagine a player more interested in having fun than in improving or making money, where we might imagine that the largest circle corresponds to play. In this case, what often happens is that teammates do not perceive any commitment from the player, which weakens the bonds they may have during training.

It is hard to ignore that play, in its paradoxical nature, seems to contain elements perceived as subversive, even when they can contribute to establishing orders and norms that later seem to transfer into social life as we experience it daily. Turning play into a form of work appears to be an expected step by the labor market, although not always well regarded in certain conditions. It is worth asking whether there are other ways in which players can experience pleasure without subjecting themselves to a precarious and stigmatized life. It is difficult to imagine a society without work, or at least one where we can enjoy our free time without feeling guilty, and perhaps this path is subversive enough to undermine the boundaries in which we encapsulate play.

References

Abramis, D. (1990). Play in Work. American Behavioral Scientist, 33, 353 – 373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764290033003010.

Black, B. (2013). La abolición del trabajo. Logroño: Pepitas de Calabaza.

Belbin, R. (2000). ‘So, what’s the job?’, 25-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-4288-0.50008-7.

Ellul, J. (1980) La ideología del trabajo. Publicado en Foi et Vie n° 4.

Frayne, D. (2017). El rechazo del trabajo: Teoría y práctica de la resistencia al trabajo. Ediciones Akal.

Graeber, D. (2018). Hacia una teoría antropológica del valor: La moneda falsa de nuestros sueños. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Lemus, Rafael (2015), Contra la vida activa, México, Tumbona Ediciones

Lafargue, P. (2012). The right to be lazy. The Floating Press.

Pargman, D., & Svensson, D. (2019). Play as Work. Digital Culture & Society, 5, 15 – 40. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2019-0203.

Petelczyc, C., Capezio, A., Wang, L., Restubog, S., & Aquino, K. (2018). Play at Work: An Integrative Review and Agenda for Future Research. Journal of Management, 44, 161 – 190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317731519.

Narasiah, M. (1997). Looking Beyond the Job: A Brief Note. SEDME (Small Enterprises Development, Management & Extension Journal): A worldwide window on MSME Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0970846419970405.

Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, Careers, and Callings: People’s Relations to Their Work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1006/JRPE.1997.2162.