Publishing is confusing and complicated. There are often barriers to understanding it fully. And the process is very rarely fully transparent. So, I’m sharing my experiences of the publishing process, and talk about why I, as a PhD student in STS, chose to go with a trade publisher over an academic one when my book went to auction. This is Part 2 of a series on publishing in academia. In Part 1 of this series I describe how I got my agent, and discuss whether or not academics need agents.

…

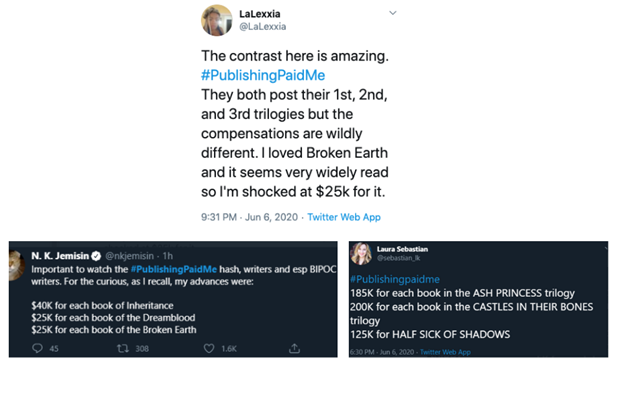

In the early 2020s the use of the hashtag #publishingpaidme prompted an unprecedented look into publishing industry standards regarding advances. Shortly following the rise of the hashtag, a crowdsourced document was created which recorded the previously unseen financial data of authors across the industry.[1] Listed were the advances of bestsellers like N.K. Jemisin and Matt Haig along with thousands of lesser-known authors. The data revealed startling discrepancies between Black authors and non-Black authors. It also acted as a stark reminder that the publishing process, from query to submission to acquisition, can be not only confusing and difficult to accomplish, but mysterious and nontransparent. Though there is a move to increase transparency, an STS scholar has to ask, why is it so hard to produce knowledge?

…

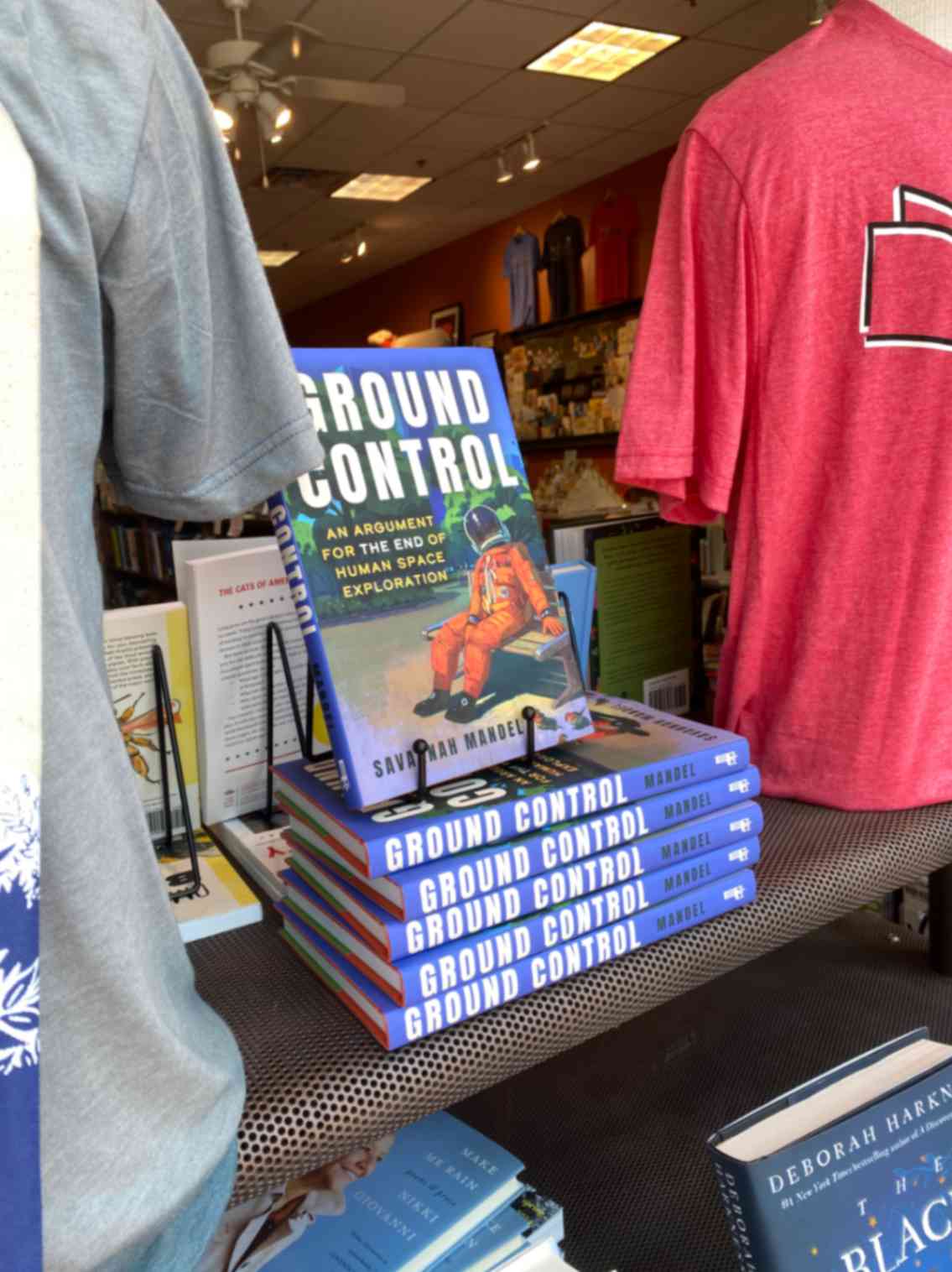

In 2022, Ground Control: An Argument for the End of Human Space Exploration went to auction, on our third round of submission to publishers. This non-fiction political commentary on space ethics was my debut book and its submission to publishers resulted in my agent and I receiving two offers from two very different publishers.[2] One offer was from an independent trade press, Chicago Review Press (my current publisher) and the other was from a well-known and highly-regarded academic press.[3]

In response to the two offers, I flew into an absolute panic. The decision between the two publishers was not simple. It was financial. It was personal. It was intellectual. It was also ideological. Chicago Review Press and its competitor each had something different to offer not just Ground Control, but my career. And this is because in the world of academia, publishing holds value. But trade and academic presses hold value differently in different worlds. As a young scholar aiming to get a job in academia, the decision between publishing with trade and publishing with an academic press felt monumental. I wasn’t facing a choice between publishers; I was facing a choice between careers. As many academics know, publishing with an academic press, such as MIT Press or Yale University Press, can often lead to promotion or a faculty position. Trade publication, however, had a completely different set of benefits.

At face value, Chicago Review Press shared a vision for my book that very much matched my own. They had an impressive marketing plan. They offered me great royalties, retention of certain rights, and an advance of just under $10,000.

The academic press offered me zero advance, very little royalties, and almost no retention of rights. However, they offered me a very specific sort of exposure, and “a chance at tenure straight out of grad school,” as one advisor put it.

If you are ever given the opportunity to choose between an academic and trade press it is not a decision to take lightly. This is because the process of publication is a part of knowledge production but different types of knowledge production are valued differently in different social circles.

Are you an early-career faculty member trying to get tenure? Publish academic. Don’t think about the money. Don’t think about the marketing. Your book will grow and acquire value through library check-outs, citations, and career promotion, not Barnes and Noble sales. Are you someone who often communicates their research to mass audiences? Or who writes their research in a commercial style? Or someone who is hoping for a career outside of academia? Then you might consider going with a trade publisher.

I didn’t make my decision alone because I was making it at such a difficult stage in my career. I met with members of my committee, one of whom authored a popular trade non-fiction book. I also sought out advice from a retired affiliate faculty member who understood how significant the prospect of being a career writer was to me (my fiction and science communication work was very important to me). I got advice from friends, family, and co-workers at the brewery I worked at—individuals who knew nothing about publishing but knew a lot about me.

I had gathered research and had several options on how to shape it. My research needed to be translated through a mode of production that would result in digestible knowledge. My choice of publisher would lead to that knowledge being constructed toward a specific audience, who will value it a certain way.

…

Was the advance that Chicago Review Press offered me a fair advance? That’s another complicated question.

There are a lot of factors at play when it comes to advances and #publishingpaidme revealed not only that there were discrepancies in advances given to authors of color (I am not a person of color) but also general issues of transparency regarding how advances are paid out. When assigning advances publishers take into account the genre of book, the size of the publisher (for example, I don’t think Chicago Review could have offered me a quarter million even if they had wanted to), anticipated interest and audience, the author’s publishing track record and established publicity (i.e. do they have a large social media following or do they already have readers?), and the type of publisher (it’s not uncommon for academic publishers to not offer an advance), among other factors.

Ground Control visible in a bookshop window. Photo by author.

When I mined data from the #publishingpaidme document I found that the average nonfiction book got an advance of around $125,000. But this data was influenced by all of the aforementioned factors and the fact that, although there were over 2,200 recorded non–fiction deals at the time, most were trade. The average was also influenced by the small collection of seven figure deals on the list.

Based on the data, I believe my advance was within a fair range. Chicago Review Press is a small press and they were buying a debut book, on a controversial topic, from an author with a very small social media following.

In the end, I chose Chicago Review Press over the academic press. Their creative vision for my book resonated with my own vision for it. Ground Control truly felt like a book better suited for the masses than solely academic audiences. It was a political commentary, not a traditional history book nor ethnography and I didn’t want to have to shape it to become either of those things. Chicago Review Press felt the same way. This press was simply the best fit for this book. It was not a decision I made lightly, nor one I made alone.

Do I regret choosing a trade press? Not even a little. But do I think it has led me down a different path than an academic press might have? Absolutely.

There have been many benefits to my choice. Financial benefits. Benefits related to marketing, sales, and publicity. But as a doctoral student who still aims to apply for faculty positions, I sometimes worry if it will be frowned upon that I write for trade. Will application boards look at Ground Control and think it’s not rigorous enough, or it’s not technical enough, or there’s not enough theory? Will they look at Ground Control and/or my other “pop culture” efforts and brush them to the side as not competitive enough? Because writing a book is competitive—but we value different kinds of books differently and in different circles. #Publishingpaidme has even showed us that we value different authors differently.

Notes

[1] See Concepción de León and Elizabeth A. Harris, “#PublishingPaidMe and a Day of Action Reveal an Industry Reckoning,” New York Times, June 8, 2020; Alison Flood, “#Publishingpaidme: authors share advances to expose racial disparities,” The Guardian June 8, 2020. You can view the data on this website, “Publishing Paid Me,” by Melanin in YA.

[2] Savannah Mandel, Ground Control: An Argument for the End of Human Space Exploration (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2024).

[3] I’ve decided to keep the identity of the academic press anonymous out of respect, not because it is confidential data.

1 Comment

Thank you, Savannah, for an incisive analysis of this question. Your points apply well to a project I’m developing, perhaps all the more so because it’s in a field quite distant from yours. Your skill in perspective-setting is admirable!