Authors’ Note: The following essay uses the words “women” and “girls” in order to mirror the phrasing and experiences of cited literature as well as the responses of the participants in our studies. We wanted to represent and relay the insights provided by all parties in the manner in which they were expressed to us directly or as they were published. This wording was not chosen to deliberately exclude the range of people who experience menstruation in Cambodia and around the world, as we recognise and understand that menstruation is not a gender-specific experience by any means. If anything, we support that MHH is an effort to be tackled by all.

Introduction

Achieving menstrual health is crucial for attaining good health and well-being, ensuring quality education and promoting gender equality. Although it is slowly gaining recognition on a global scale, menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) needs are still not met in many countries. Particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many girls are not informed or prepared before experiencing their first period (Chandra-Mouli & Patel, 2017). In Cambodia, girls and women follow strong cultural beliefs about menstruation, such as avoiding certain foods and drinks when on period (Sommer et al., 2014). Information is seldomly provided, as the topic is not openly discussed at home and teachers lack confidence to educate about reproductive health (Conolly & Sommer, 2013). WASH infrastructure in schools is inadequate with not enough toilets and a lack of privacy, leading to feelings of discomfort and avoidance of facilities (Sommer et al., 2014, Conolly & Sommer, 2013). This results in menstrual accidents like leakages, and being labeled as unhygienic (Daniels et al., 2022). If MHH needs are not met, girls experience fear and shyness throughout menstruation, impacting their lives by having to miss social activities, transit locations to change sanitary pads, and missing school days (Daniels et al., 2022).

To break down negative social norms around menstruation and to ensure that people feel safe and comfortable accessing menstrual hygiene resources, a spotlight must be put on education. For instance, this was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport (MoEYS) by implementing the Comprehensive Sexuality Education Curriculum for grades five to twelve in 2015. Despite those efforts, menstrual health education in Cambodia remains under-explored.

Researching in Cambodia

Driven by the need for a deeper understanding of MHH education in Cambodia, we decided to conduct two qualitative studies. We were excited to start this journey of research, keeping in mind our own positionalities considering menstrual health and being open to learn about Cambodian culture and values. Both projects focused on analyzing work carried out by Green Lady Cambodia (GLC). Since 2019, GLC is a local NGO which has been providing menstrual products and contributing to MHH education, mainly in secondary schools.

A display of Green Lady Cambodia products in a store in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. (Credit: Isabell Hedke)

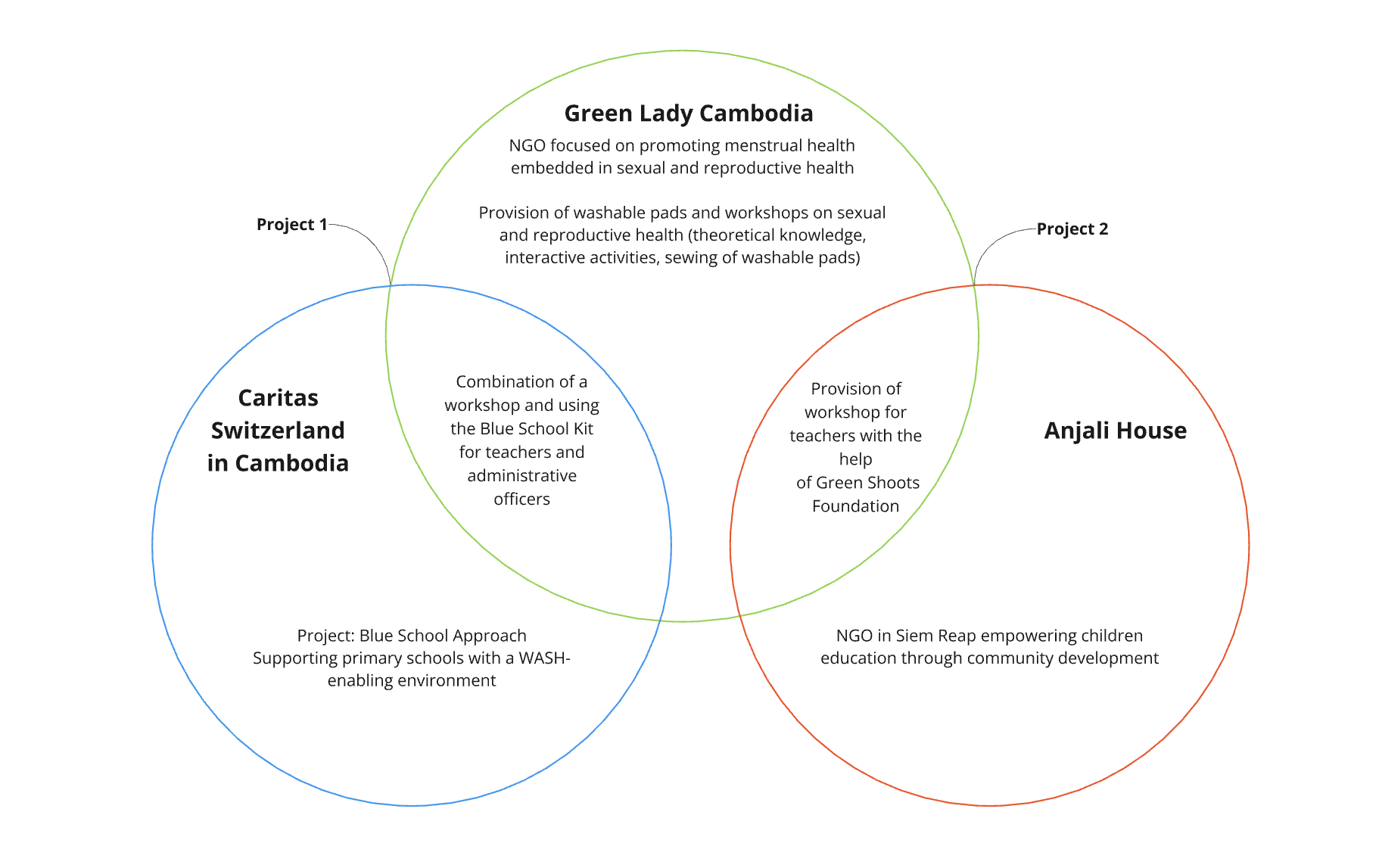

Isabell’s project (Project 1) focused on studying a MHH workshop which was facilitated by GLC in collaboration with Caritas Switzerland in Cambodia (CACH) in August 2023. CACH is currently implementing 78 Blue Schools in the Banteay Meanchey Province. The approach supports primary schools in becoming WASH-enabling environments. The Blue School Kit is a curriculum based on this aim, which guides teachers in educating students. MHH is included in Topic 3 which focuses on ‘Growth and Change’. The aim of the qualitative study was to understand strengths and weaknesses in educational activities of both organizations by analyzing the workshop setting. Twelve semi-structured interviews with organization staff and workshop participants including teachers and administrative officers of the MoEYS were conducted. Placing the focus on this participant group enabled the study to analyze a Training of Trainer (ToT) setting which has potential to contribute to a systematic change of health education within schools.

Aikaterini’s project (Project 2) aimed at evaluating the menstrual health educational model of GLC used for young girls and boys studying at Anjali House. This NGO offers education to young students through community development in Siem Reap. Through their collaboration with GLC and Green Shoots Foundation, an NGO focusing on promoting development programs in many LMICs, they offered menstrual health workshops to the students. By conducting seven semi-structured interviews with school staff and instructors of Anjali House, a better understanding of the opportunities and challenges that arise for students learning about menstrual health was gained. Figure 1 provides an overview of the connections between organizations of both projects.

Figure 1: Overview of connections within Project 1 and 2 between Green Lady Cambodia, Caritas Switzerland in Cambodia and Anjali House (Credit: Isabell Hedke)

Findings on Menstrual Health and Hygiene Education in Primary Schools

When placing teachers in the center of health education and promotion, it is pivotal to train them accordingly. Even if ToT can be difficult and requires lots of resources, it is valuable to reach many students and maximize educational efforts. The teachers and administrative officers from both projects emphasized the need for appropriate information and guidance, for themselves, before they are able to teach students about MHH. Both projects have complemented each other in finding that workshops, as well as mixed-method designs including supplementary guidance through books or other learning material, can be important ways of ToT.

A challenge we discovered in learning environments was the power dynamics at play. In Project 1, female teachers shared that they felt uncomfortable asking questions in front of their male colleagues. Administrative officers were seen as more powerful, impacting teachers’ openness and courage in discussions. In Project 2, it was explained how discussing menstrual health concerns or addressing the need for menstrual hygiene materials in households was considered impolite and avoided in the presence of men.

Women sometimes feel embarrassed and ashamed to let their father see that they use sanitary pads, in the toilet for example. (Project 2, PA)

These examples can be linked back to the Code of Conduct for Women and the Teacher’s Code of Conduct, which shape their role in society. Both are rooted in patriarchal expectations and reinforce that one should not speak out of turn (Anderson & Grace, 2018). Taking these social and gender norms in consideration when talking about MHH means that there needs to be creative solutions which encourage exchange and discussions between various groups. Both projects have highlighted that GLC has introduced innovative educational activities to achieve this. For instance, an anonymous question box and body-mapping game stimulated collaboration and shared understandings. Gamification and advancing the traditional classroom setting have also contributed to making education more interactive, achieving a higher degree of participation and willingness to learn on the part of all participants. While challenges due to perceived power dynamics remain, it is key to provoke them to contribute to systemic change, not only in regard to MHH but also beyond.

Both projects allowed us to understand teachers’ perspectives on what is needed in the classroom when discussing menstrual health. To advance education, teachers in Project 1 explained that having materials in a textbook or hung up on the wall for students to review can be helpful.

Print some pictures out to show to the student, like take picture and show in the classroom. (Project 1, P10)

This idea highlights two challenges with MHH education in Cambodia. Firstly, as resources are already limited, providing teachers and students with more information is difficult due to additional costs. Secondly, while the use of sexual and reproductive health visualizations and illustrations is valuable, recent developments such as the new Cybercrime Law could prohibit all descriptions and depictions of genitalia. This makes it even more important to use creative approaches, such as GLC’s origami mode of teaching about genitalia.

When looking at differences of teachers’ abilities to educate, male teachers in Project 1 shared that it is more difficult for them, as they have no or limited personal experience with the topic. However, considering that all teachers often have to educate about ideas and topics they have no firsthand experience with, it should not be a reason for male teachers to be excluded from learning and teaching about MHH. Indeed, male teachers shared that they are willing and motivated to learn and engage more in this topic to be able to help their students manage their periods, but might need more input than female teachers before being confident to do so. Looking at it from another angle, Project 2 adds that male students opened up and were more engaged in discussions without feeling shy when a male teacher was present. Therefore, investing in their understanding contributes to all-gender health education and towards expanding menstruation’s perception of only being a “woman’s problem.” Educated teachers and students, regardless of their gender, can help stop the cycle of perpetuating stigmatizing norms and stereotypes onto next generations.

Those teachers and also the student themselves that receive the training and education will have the discussion with their parents, to see like or try to challenge like what the parents believe and what the grandparents believe. (Project 1, P6)

This includes overcoming misconceptions such as thinking that people have to avoid showers during menstruation, believing that period blood is dirty, and passing on traumatic experiences.

What Our Research Contributes

What we have learned from both research projects is that educational efforts can initiate a positive feedback loop which affects not only individuals who participate in the workshops, but the wider community as well. This is why MHH education in schools paves the way for intergenerational knowledge transfer as current teachers and students can continue the discussions at home. This interplay between individual, community, and educational factors requires attention and good collaboration among various stakeholders.

We have also seen that it is essential to acknowledge complex challenges faced by Cambodia’s education sector. Limited resources minimize the success of efforts, and cultural sensitivities surrounding gender and sexuality impact how certain topics are perceived and information is provided. Aiming for creative methods can be helpful in overcoming these challenges.

To achieve this and foster a stronger alliance between stakeholders, it could be beneficial to advance the Comprehensive Sexuality Education Curriculum. Our research has found that access to MHH education is needed before youth begin to menstruate, which is why the curriculum has potential to guide primary schools too. Also, we believe that bringing in ideas and learnings from NGOs which advocate for menstrual health is crucial. These insights can derive from both local and external organizations which can provide community-driven initiatives while not neglecting the local perspective. This can ensure the sustainability and feasibility of current educational efforts. Considering that we ourselves are external researchers, even though we can add value, we also need to remember the importance of remaining self-reflective and critical about cultural sensitivity.

Overall, we have observed that due to deeply rooted traditional norms and historical challenges in Cambodia, the topic of menstrual health has not gained much attention in the past. However, while the mode of survival and the priority of rebuilding the nation after the Khmer Rouge still shapes younger generations, efforts to advocate for women’s health continue to grow. GLC has grown from providing washable pads into an organization promoting menstrual health with far-reaching impact. This shows that an individual’s health concern, which might seem insignificant on a societal level, can develop into a purpose to address a shared concern. This highlights how we must not forget that efforts from individuals and communities are immensely valuable to achieve and sustain health for all.

Notes

Caritas Switzerland in Cambodia

Green Shoots Foundation Cambodia

References

Anderson, E., & Grace, K. (2018, December 29). From Schoolgirls to “Virtuous” Khmer Women: Interrogating Chbab Srey and Gender in Cambodian Education Policy. Studies in Social Justice, 12(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v12i2.1626

Chandra-Mouli, V. & Patel, S.V. (2017, March 1). Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle- income countries. Reprod Health 14, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0293-6

Conolly, S. & Sommer, M. (2013). Cambodian girls’ recommendations for facilitating menstrual hygiene management in school. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development; 3 (4): 612-622. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2013.168

Daniels, G., MacLeod, M., Cantwell, R. E., Keene, D., & Humprhies, D. (2022). Navigating fear, shyness, and discomfort during menstruation in Cambodia.PLOS global public health, 2(6), e0000405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000405

Sommer, M., Hirsch, J. S., Nathanson, C., & Parker, R. G. (2014). Comfortably, Safely, and Without Shame: Defining Menstrual Hygiene Management as a Public Health Issue. American journal of public health, 105(7), 1302–1311. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525