Gun violence in the United States is a statistical crisis, a political flashpoint, and an everyday reality for millions. But what if we could play through its structural logics? My game Seven Days of Destruction invites players into a speculative environment where systemic poverty, miseducation, drug abuse, and inequality are not only themes but mechanics. By designing this game, I sought to intervene in the ways we narrate and engage with structural violence: not through direct representation or journalistic realism, but via allegory, abstraction, and the aesthetics of defamiliarization.

This project also emerged from a specific moment of collective grief and anxiety at the University of Chicago. Between 2020 and 2021, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple international students—many from East Asia—were fatally shot on or near campus. These incidents shocked the university and the surrounding South Side community. For weeks, students, staff, and neighbors were caught in cycles of mourning, protest, and fear, asking: Why here? Why now? Why them? As the discourse oscillated between calls for more policing and concerns about racial profiling, I became increasingly interested in exploring the structural conditions—economic, educational, psychological—that underlie such acts of violence, especially after experiencing personal loss from these fatal shootings. Seven Days of Destruction is my attempt to create a system where those invisible forces can be felt.

From Proceduralism to Design Ethnography

Digital games have emerged as a powerful medium for persuasion, capable of modeling complex systems and simulating ethical dilemmas. As persuasive games, they do not merely entertain; they embed arguments within their mechanics, requiring players to engage with systems that reflect real-world structures. Ian Bogost (2007) defines this as “procedural rhetoric”: the practice of persuading through rule-based representations that mirror how social or political processes work. Unlike visual or textual rhetoric, procedural rhetoric engages the player through action—through doing rather than observing. This is what makes games uniquely capable of modeling systemic problems such as poverty, surveillance, and violence (Bogost 2007).

Game scholars have long debated how this persuasive potential is best realized. Bogost emphasizes procedural rules; Sicart (2011) counters with the importance of ludic freedom and player interpretation; while Galloway (2006) highlights hybrid affordances where both systems and actions matter. While these perspectives offer valuable insights, I argue that the immersive and rhetorical power of games lies in the design process itself. Drawing from the Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics (MDA) framework—a game design model that connects how rules (mechanics), player behavior (dynamics), and emotional experience (aesthetics) interact (Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek 2004)—and postphenomenological media theory, which explores how technologies shape human experience and perception (Ihde 2010), I conceptualize game design as a form of speculative ethnography—an experimental mode of inquiry that creates fictional yet plausible environments to explore real-world social conditions. In this framework, design becomes a research method: building a system is itself a way of asking anthropological questions about agency, constraint, and survival within unjust structures.

In Seven Days of Destruction, players are not told what poverty or inequality feels like. Instead, they must act within a constrained system in which survival demands ethical compromise. They are compelled to make decisions under pressure, constrained by a logic they did not choose but must inhabit.

The Game: A Brief Overview

The player begins Seven Days of Destruction trapped in a haunting, hermetic iron cube. Stripped of name, gender, race, and background, the avatar—designated only as “No. 45002”—is a non-identifiable figure meant to detach the player from social assumptions and encourage defamiliarized immersion. The cube contains an old book, a broken toilet, three candles, seven eerie dolls, and two dominant figures: a cybernetic AI box and a surveillance mask that mimic the architecture of algorithmic control and digital authoritarianism. These figures issue commands, monitor behavior, and simulate the disciplinary logic of power.

The surreal and confined environment where the avatar awakens. Image by author.

The cybernetic AI box issues commands, while the surveillance mask tracks the avatar’s movements with a rotating gaze. Image by author.

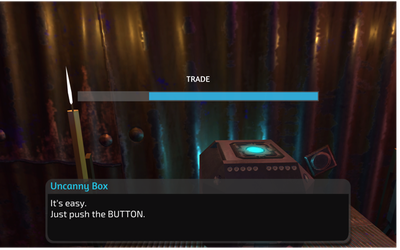

To survive in the cube, the avatar must trade with the system via a “TRADE” button. Each press escalates the avatar’s moral compromise: first stealing, then committing armed robbery, then gun homicide. The trade system operates under false choice. Though options are presented (e.g., “Yes” or “No”), refusal leads to starvation and game termination, echoing real-world conditions in which those facing poverty may have no viable alternatives. With each trade, the avatar loses a part of its ethical agency, becoming a vessel through which systemic pressures act.

The AI box activates the trade button, coercing the player into ethically fraught decisions under systemic pressure. Image by author.

After the second act of violence, the avatar is offered a simulated escape through drug use. By following the book’s guidance, the avatar enters a psychedelic landscape called “Wonderland,” evoking Baudelaire’s (1860) notion of “artificial paradises.” This expansive, surreal world entices the player to explore and collect coins to buy clues about why they are imprisoned. Unbeknownst to the player, each exchange for clues is fueled by virtual meth and results in another unseen gun murder.

The Wonderland: a psychedelic escape where players collect clues to piece together the reasons behind the avatar’s imprisonment. Image by author.

In this second level, players are tasked with collecting coins scattered across Wonderland to exchange for narrative clues that explain the avatar’s imprisonment. What players are not immediately told is that each coin traded for a clue corresponds to the avatar consuming more meth to remain in the altered state. Worse, each trade simultaneously triggers an offscreen gun murder, metaphorically illustrating how addiction and systemic violence are often invisibly linked. The avatar becomes an unwitting participant in continued violence while chasing understanding and survival.

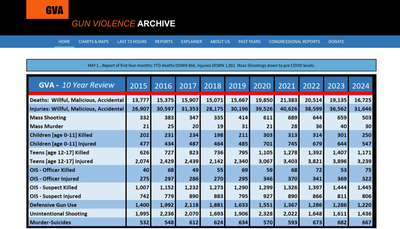

Toward the end of the second level, players are required to solve a Morse code puzzle embedded in the environment. Successfully decoding the message yields a single word—“archive”—which, when entered into the browser, directs players to gun violence archive, a real-time online database documenting gun-related incidents across the U.S. This final act grounds the symbolic horror of the game in the material reality of everyday American gun violence, bridging speculative fiction with empirical crisis.

A screenshot from the Gun Violence Archive, the real-world database players are directed to in order to confront the scope of gun violence in the United States. Image by author.

After this revelation, the avatar returns to the original cube, now transformed into a final sentencing space. The once inert seven dolls now stand in a semi-circle, each one associated with a name, backstory, and personal history of a real-world gun violence victim. In this closing scene, players learn that each of the seven trades made in Wonderland—each moment of meth-induced pursuit of truth—was paid for with a life. The AI box narrates the cumulative toll of the avatar’s actions, and the surveillance mask remains fixed, silently reinforcing the inevitability of systemic complicity. The game ends not with escape or redemption, but with confrontation and responsibility.

Designing Allegory: Defamiliarization and Constraint

Rather than reproduce social realism or specific cases (as in We Are Chicago or Super Columbine Massacre RPG!), I adopted indirect design strategies. The game draws from science fiction and horror to build an uncanny space: clay dolls with real victims’ backstories, an AI that speaks in moral paradoxes, a trade button that oversimplifies but intensifies the ethics of survival. These mechanics allegorize the limited agency experienced by those in poverty. While the narrative is linear—all choices lead to entrapment—the affective impact lies in this very lack of escape. Constraint, not freedom, becomes the site of reflection.

This approach builds on Viktor Shklovsky’s (1917) concept of defamiliarization and Freud’s (1919) notion of the uncanny. Players are not allowed to comfortably identify with a protagonist; the avatar has no name, gender, or race. Instead, they are forced to act within a strange yet eerily recognizable system. The result, ideally, is not empathy through identification but through discomfort.

Playtesting as Ethnographic Feedback

To test the game’s impact, I conducted a hybrid playtest with thirty international graduate students. Most found the game immersive and correctly identified its themes. Many appreciated the allegorical mechanics. Yet, the game had limited influence on their real-world behaviors (e.g., donations or advocacy). This suggests a key tension: while games can induce reflection, they may not directly change behavior. This echoes findings in serious game literature, but also raises a design question: what kind of time, context, or community is needed to translate reflection into action?

Some participants questioned the use of abstraction for such a concrete issue. Others asked why this needed to be a game at all. My answer lies in the embodied logic of play: unlike a film or novel, games force players to act within systems. They can quit, but they can’t spectate passively. In this sense, Seven Days of Destruction offers a form of speculative ethnography—one where systems are not described but enacted.

Toward a Politics of Constraint

I do not claim that those in poverty are fated to commit violence, nor that abstract representations can replace political solutions. But by staging soft determinism within a game space, I aim to reveal how systemic pressures contour agency. The illusion of choice in the game mirrors the constrained options many face in real life. As anthropologists and designers, we might take seriously this design logic of constraint—not as a pessimistic closure, but as a critical invitation. If the system is unplayable, perhaps the rules need rewriting.

In future iterations, I hope to explore non-linear narratives and augmented reality formats that blur the boundary between game and world. But for now, Seven Days of Destruction stands as a design experiment: one that asks not how we represent violence, but how we build systems that make it inevitable—and how we might reimagine them.

How to Access and Play the Game

To download and experience Seven Days of Destruction on your own computer:

🖥 Game Download (Mac/PC)

▶ Game Walkthrough (Video Recording) for those with limited time or who want to preview the gameplay (here is a textual description of the video walkthrough) :

🔧 Installation Instructions (Mac):

- Download the .zip file from the Google Drive link.

- Unzip the file by double-clicking it.

- Locate SevenDaysOfDestruction.app in the extracted folder.

- Right-click (or Control + Click) on the app file and choose “Open.”

- You may see a warning: “SevenDaysOfDestruction is from an unidentified developer. Are you sure you want to open it?” Click “Open.”

- If blocked, go to System Preferences → Security & Privacy → General, click “Open Anyway,” and enter your Mac admin password.

- The game should now launch.

This post was curated by Multimodal Contributing Editor Chen Shen.

References

Bogost, Ian. 2007. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Freud, Sigmund. 1919. “The Uncanny.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XVII, edited by James Strachey, 217-256. London: Hogarth Press.

Galloway, Alexander R. 2006. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hunicke, Robin, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek. 2004. “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research.” Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI.

Ihde, Don. 2010. Heidegger’s Technologies: Postphenomenological Perspectives. New York: Fordham University Press.

Shklovsky, Viktor. 1917. “Art as Technique.” In Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, translated by Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis, 3-24. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

Sicart, Miguel. 2011. “Against Procedurality.” Game Studies 11 (3). Gun Violence Archive. 2021. https://www.gunviolencearchive.org.

Baudelaire, Charles. 2000. Du vin et du hachisch, suivi de Les Paradis artificiels. Edited by Jean-Luc Steinmetz. Paris: Librairie Générale Française.