In 2015, I was back in India’s capital city, Delhi after two years of fieldwork in villages in rural parts of the country. On my return, the city had changed. There was something different in the atmosphere, which was leading to far-reaching, unexpected effects. For instance, during my morning commutes as I turned on the radio to one of Delhi’s most popular radio stations the radio jockey blared every hour or so, ‘Hawa-laat’! The Hindi word Hawalaat translates as a prison. If the word is broken into two parts, Hawa and Laat, it signifies a kick by the wind, as Hawa means wind or air and Laat means a kick. The radio jockey called out the word in a long and stretched manner to get the listener’s attention, slowly elongating the word ‘Hawaaaaaaaaa’ and then abruptly ending with a forceful ‘Laat!!!’, bringing out the potency of the wind (air) kick we were all getting. Following this, air pollution levels were detailed, and listeners encouraged to indulge in carpools and get their vehicular pollution levels checked.

I had lived in the city since 2004, but never heard it characterized in such a way. Only since 2014 has there been increasing traction in science, policy, and advocacy on air pollution in Delhi and the city has consistently remained one of the most polluted globally (Express News Service 2025). In the last decade, the air in Delhi has become emblematic of a toxic atmosphere, an ‘all enveloping experience’ (Ingold 2011, 134) in and through which people perceive to ‘simultaneously evoke both a body of air or even simply space, along with its prevailing affective characteristics’ (Gandy 2016, 354). If airtight cities do not exist, how can we make sense of the hawalaat?

Delhi’s skyline in 2015. Image by Author

Atmospheres are ecological formations, encountered materially and created discursively, that exist as lived achievements while evading any form of human or technological capture. The air we live and breathe in carries substances while it continues to flow and swirl beyond any human-made boundary. Air’s materializations cannot simply be thought of as natural or artificial but must be approached as ‘open-ended practices’ (Barad 2007, 146), such that atmospheres are ‘[…] material discursive practices […] that are formative of matter and meaning’ together (Barad 2007, 217). I will demonstrate this in how the air filter and the air quality monitoring station serve as material discursive practices for understanding the formation of the hawalaat; a porous, permeable prison that engulfs residents and simultaneously dissolves the city, diffusing it, into regional expanses.

Hawalaat

Efforts to tackle air pollution in Delhi are traceable as far back as the colonial period, when governance focused on enclosing some bodies from the threating air, by architectural sequestration, zoning, air-filtering green belts and migration to ‘hill stations’ to escape suffocating cities (Ghertner 2021). In the 1990s, these efforts came to the fore in the change of a diesel based public transport system to compressed natural gas (Raman and Mukherjee 2019). Yet, it was only in May 2014 for the first time; Delhi became infamous for having become the most polluted city in the world. This infamy resulted from the release of the World Health Organization (WHO) database detailing annual averages of pollution levels in cities across the globe (WHO 2014).

Historically, the quantification of air pollution was made possible through developments of scientifically accurate standards that qualified the quality of air (Boer 2016). In these processes, the individual perception of the quality of air in a place – through smell, temperature and movement – was replaced with technological mediation that standardized air’s effects on human well-being. The technological device that allowed for this transformation is the air filter, and it remains seminal today in scientific assessments of air quality (CPCB 2013, 2018), such as the air quality index (AQI). The AQI is a weighted average that relates levels of pollutants in the air to human health, along a range of ‘good’ to ‘severe’. The Central Pollution Control Board and the Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change launched the Indian version of the AQI in 2014. Since then, the AQI has become the barometer of air quality in a city such as Delhi.

Interrogating this issue led to conversation with an air quality WHO representative based in the Geneva office, officials from pollution control boards in Indian cities and a close reading of air quality data published on varied platforms. These engagements revealed that the difference in city-level infrastructure and attempts to standardize and communicate air as an index are compounded at three levels – international, national, and city. First, though based on official sources, international air quality data for cities across the WHO database vary in terms of the number of air quality monitoring stations in a city, their placement, and different measuring methods (WHO 2016). Second, at the national level, not all cities in India are easily comparable. For the AQI to be effective, air quality must be monitored in real-time through continuous air quality monitoring stations. Most cities in India have manual air quality monitoring stations, which means someone must physically go to the station, take out the air filter and then analyze it in a laboratory. Thus, data on air quality is often available weeks after the day/time that it represents. Delhi has the maximum number of continuous air quality monitoring stations in the country, 40. The city that comes second is Mumbai with 11 stations. This means Delhi generates the most real-time data of any city in India. Third, at the city level in Delhi, monitoring stations are not evenly distributed; though state agencies have pledged to increase this number.

All three levels are further complicated as there is contestation over the factors that affect air quality in Delhi, which are a combination of local and transboundary sources (beyond state and national boundaries). Not only do particles such as dust from intercontinental air corridors make the air in Delhi but in air’s movements, particles and aerosols that mix and move within the city are carried off to adjoining and far-off regions too. Our intimate entanglement with air then, must acknowledge the inability to hold or contain air. It is precisely for this reason that the statement ‘the air ‘in’ Delhi’ is more apt than saying ‘Delhi’s air’, as a city cannot enclose air.

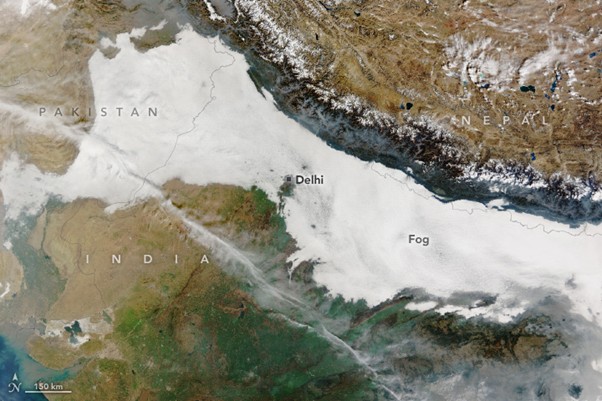

‘Fog Blankets the Indo-Gangetic Plain’. Courtesy NASA Earth Observatory image by Wanmei Liang, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview, January 15 2024. Public Domain.

Experts ascertain that air pollution is a regional phenomenon engulfing the Indo-Gangetic Plains that encompasses northern and eastern India (including Delhi), eastern Pakistan, southern Nepal, and almost all of Bangladesh (Hameed et al. 2000; Ramanathan and Raman 2005). This regional assessment too requires the mediation of human-made science that seeks to quantify the effects of materials in the air inhaled by breathing bodies. However, in popular discourse the air pollution problem in the Indo-Gangetic Plains remains a largely urban issue. My intent then is to interrogate how Delhi became a hawaalat since 2014, a city that seemingly encloses air in popular imagination, and not lose sight of the slippery and ephemeral planetary circulations of air.

Viscosity

The hawalaat is activated in three synchronous ways. First, as a material discursive practice it encloses the city from regional atmospheric circulations; second our intimacy with air is realized through its toxicity (which I understand through viscosity) and third, the hawalaat as enclosure exists as a fragile porous happening that dissolves and distributes the city into regional expanses. All three operate together and bring forth the hawalaat. In this compositional worlding human action is but one of the elements that compose the politics of this myriad place that escapes capture in any scientific (or human-induced) encapsulation and delineation.

As a fragile enclosure, post 2014 residents of Delhi recognize the dense opaque shroud hanging in the air in the winter months as ‘pollution’ that has detrimental effects on human health. Previously, it was commonly referred to as ‘fog’ or just indicative of winter descending. In M. Mukundan’s novel ‘Delhi: A Soliloquy’ (2020) spanning four decades (1960 – 2000) in the city, the word ‘fog’ is repeatedly used. For instance, ‘A thick fog enveloped the city [….] Delhi became like a black and white photo in the fog’ (86). This means that while the intensity of pollution in the region has been progressively intensifying, the material-discursive hawalaat encoding toxic air was only popularly formed 2014 onwards, which makes and marks residents intimacy with air.

To understand, this strong intimacy with air I rely on Timothy Morton’s (2013) use of Sartre’s notion of viscosity. For Sartre, viscosity is how a hand feels when it plunges into a large jar of honey. The important point is that viscosity is not indicative of a leap that has been made into the honey but consists of the realization that we are already inside the honey. In a similar vein there is a realization that air envelops and penetrates our very existences. This form of intimacy allows for the contemporary recognition of how we come to be with freely flowing air, layering the ways in which porosity operates and changes.

While in popular imagination the city encases toxic air, through science-based climate simulations, Delhi emerges as a particularly populated space caught in regional atmospheric circulations in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The air that makes the hawalaat carries a city, people and ideas beyond the space it represents in its material-discursive travels. It diffuses into viscous weather events that swirl to planetary dimensions, such that the hawalaat crystallizes and dissolves together.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Misria Shaik Ali and reviewed by Clarissa Reche.

References:

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press.

Boer, Wulff. 2016. “Synthetic Air.” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation History, Theory, and Criticism 13 (2): 76-101. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/659123

CPCB (Central Pollution Control Board). 2013. Guidelines for the Measurements of Ambient Air Pollutants. Volume –II. Guidelines for Manual Sampling and Analyses. Ministry of Environment & Forests. https://cpcb.nic.in/openpdffile.php?id=UHVibGljYXRpb25GaWxlLzk5OV8xNzM1NjIyNTA0X21lZGlhcGhvdG8xNjkzMC5wZGY=

______ 2018. 1st Revised Guidelines for Continuous Emission Monitoring Systems, Central Pollution Control Board https://cpcb.nic.in/upload/thrust-area/revised-ocems-guidelines-29.08.2018.pdf

Express News Service. 2025. “Delhi world’s most polluted capital again: Report.” The New Indian Express, March 12. https://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/delhi/2025/Mar/12/delhi-worlds-most-polluted-capital-again-report

Gandy, Matthew. 2016. “Urban Atmospheres.” Cultural Geographies 24(3): 353–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474017712995

Ghertner, Asher D. 2021. “Postcolonial atmospheres: air’s coloniality and the climate of enclosure.” Annals of American Association of Geographers 111: 1483–1502. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1823201

Hameed, Sultan; M. Ishaq Mirza, B. M. Ghauri, Z. R. Siddiqui, Rubina Javed, A. R. Khan, O. V. Rattigan, Sumizah Qureshi, Liaquat Husain. 2000. “On the widespread winter fog in Northeastern Pakistan and India.” Geophysical Research Letters 27(13), 1891–1894. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GL011020

Ingold, Tim. 2011. “Toward an ecology of materials”. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41: 427-442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145920

Morton, Timothy. 2013. Hyperobjects. Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minnesota University Press.

Mukundan. M. 2000. Delhi: A Soliloquy. Translated by Fathima. E.V. & Nandakumar K. Westland.

Ramanathan, V. & Ramana, M. V. 2005. “Persistent, widespread, and strongly absorbing haze over the Himalayan foothills and the Indo-Gangetic Plains.” Pure and Applied Geophysics. 162: 1609–1626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-005-2685-8

Raman, Anisha and Mukherjee, Polash. 2019. “Fighting air pollution in Delhi for 2 decades: A short but lethal history.” Downtoearth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/air/fighting-air-pollution-in-delhi-for-2-decades-a-short-but-lethal-history-67585

World Health Organization. 2014. Air Quality Database. Accessed 12 March 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/air-pollution/who-air-quality-database/2014

______ 2016. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution database, by country and city. Accessed 17 June 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/air-pollution/who-air-quality-database/2016