We are in Ruzaevka, a small town near Saransk, the regional capital of Mordovia, Russia. Ham radio operator Dmitry Pashkov, photographer Sergei Karpov, and I climb the roof of the local technical college. Sergei and I are on the roof because we are interested in so-called bottom-up space exploration. Dmitry works at this college as an IT specialist. It is a cloudy day in March, and there is a cold wind on the roof, still icy from the winter. Dmitry promises to show us how to get an image of the European part of Russia using an American weather satellite.

Launched in the 1970s and 1980s, these weather satellites orbit around the Earth, recording images and sending them as signals to Earth. By and large, their images are no longer used by meteorological services, but the technology continues to work reliably and, if you intercept their signal, you can receive a photo from the orbit as a souvenir. To do this, you need a homemade antenna made from a ski pole, a receiver purchased on AliExpress, and a laptop with a simple open-source software installed. We have all of this and today we hope to capture an image from space. There is a desk already set up on the roof of the college. We set our laptop down on it. Then Dmitry tries to pull another antenna out of the ice on the roof. “Oh, I thought we took it away in the summer!” he exclaims in surprise. Having calculated the satellite’s flight trajectory, Dmitry explains that we have a ten-to-fifteen-minute window to receive the image. We pull an extension cord onto the roof and set up the equipment. It’s starting to get dark.

Ham radio operator Dmitry Pashkov. Image by author.

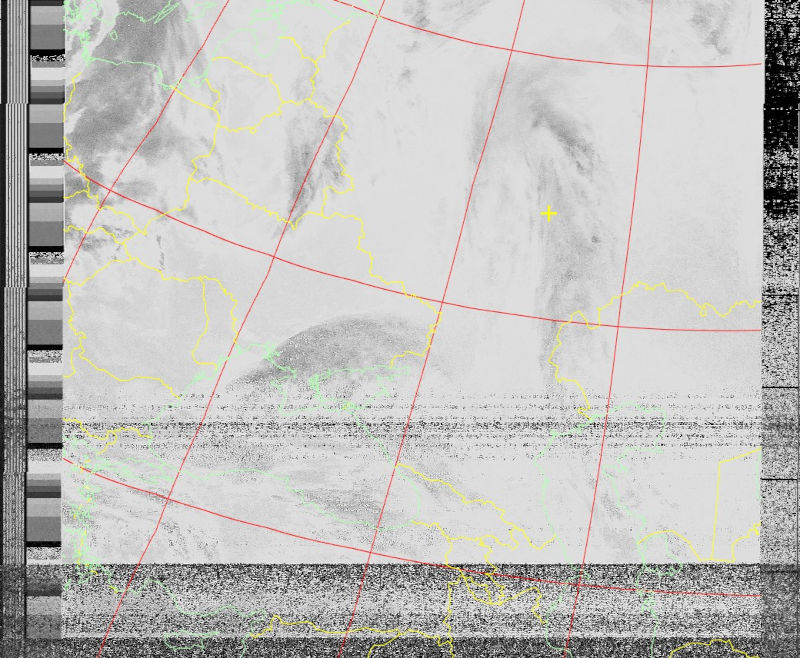

The satellite flies by and we catch the signal, but nothing works. There is too much interference from cellular communications, network filters, and other terrestrial sources of electro-magnetic pollution. Black stripes crisscross the resulting image. “It is best to intercept signals in empty fields,” says Dmitry. Second best is a small town like Ruzaevka, where there is less interference compared with a big city, and ham radio enthusiasts have a much better chance of receiving a clear signal.

This satellite flies away and we decide to try to contact another similar satellite with a different antenna—the antenna that has been lying on the roof since the summer. This one is taller and thus more powerful. Now, the wind is picking up. We need to connect several wires, so I run down to the lab for a soldering iron. I return to the roof, but it’s so cold that the soldering iron doesn’t want to heat up. I suggest giving up and going downstairs to warm up: “Well, it didn’t work out. No big deal. We understand the principle.”

“We started, so now we have to finish!” objects Dmitry, who is setting up with his bare hands in the cold.

The ham radio enthusiast connects the antenna to the receiver, another satellite flies over us, and we finally get an acceptable image on the laptop. The black-and-white image shows the large part of Russia from space and our location is marked with a yellow cross. Frozen but happy we begin to go down the stairs. Before the descent, Dmitry tells us that last summer, he and his college students tried to direct a laser pointer upward, hoping that the satellite image would capture it and show a point in Ruzaevka, but they haven’t succeeded yet. Unfortunately, there is no trace of the pointer in the image from space. “They are taking a space selfie!” I note to myself. With the ski pole and other DIY tools, these ham radio enthusiasts take pictures of themselves with a satellite flying somewhere high above and far away.

The image from the weather satellite. Ruzaevka is marked by a yellow cross. Used with permission from Dmitry Pashkov.

Later, as we sat warming up and drinking wine, we talked about switching between home and orbit with Dmitry:

Sergei: Tell me—I have a silly question—you’re sitting there listening to all of this [signals from satellites — D.S.]… You find yourself in this global expanse. Do you feel yourself as though in a global space expanse?

Dmitry: Well, I do have that feeling, yes.

Sergei: How do you then come back to this: fixing Windows, rebooting computers? Doesn’t it all weigh on you?

Denis: Taking your daughter to the kindergarten…

Dmitry: On the contrary, I can’t sit in one place, constantly listening [to satellites] there [on the roof] nor stay at home [doing something]… I just can’t sit in one place!

Sergei: So, you easily break away from this globality and switch to your everyday life?

Dmitry: Yes. Like now, let’s say, I just got here… I listened [to the satellites], went over there, did something, and came back. I can’t stand monotony. I don’t know why. Some people like it. Some people come home from work, lie down on the couch and read the newspaper. I just can’t lie down like that…

What if the contrast of home world in Ruzaevka and the satellites in the orbit refer to a special practice of scaling? As anthropologist David Valentine said in one of his lectures, “outer space is the domain par excellence for thinking in scalar terms” (Valentine 2024). Indeed, researching and exploring outer space means scaling the large and the small, the distant and the near, the familiar and the unfamiliar. The colonization of outer space is often presented as an extension of Earth to the orbit, the Moon, Mars, and beyond. Anthropologist Anna Tsing suggests speaking about scaling in terms of expansion: “Scalable projects are those that can expand without changing” (Tsing 2015, 507). From this perspective, it would seem that Dmitry is simply attempting to physically reach outer space to expand his sense of home from Ruzaevka all the way to the orbit.

But resistance, like interference in the case of the Ruzaevkian radio ham, calls into question the possibility of scaling as expansion. Latency, as Valentine points out, also matters for how we think about outer space (2024). The further away from Earth, the more time a signal takes to reach it. A signal from Mars to Earth takes between three and twenty-two minutes. A signal from the Voyager probe located outside the solar system reaches the Earth in about eighteen hours. In addition to distance, other factors—such as vacuum, temperature fluctuations, radiation, and space debris—make homologous transformations difficult. When scaling in outer space, one has to account for the unreliable connections or fragile relations.

Elsewhere, anthropologist Valerie Olson speaks about the “sensibilities of scalarity,” noting that “spaceflight practitioners and advocates routinely make things and processes seem contiguous at scale, such as linking home spaces with planetary spaces, human consciousness with cosmic systems, and human footsteps on planets with human evolution” (2018, 31). Inter-scalarity convinces us that scaling, especially in space, is not growth, expansion, or absorption, rather it is a relationship or a connection between places, thanks to which the scaling effect arises (Hecht 2018).

By attempting a space selfie, ham radio enthusiasts are not expanding their home to the size of the universe, nor are they simply connecting home and places in the outer space. As Dmitry notes in his account of regular switching between being part of the global expanse and pursuing his everyday responsibilities, they practice scaling, whilst staying attuned to the incommensurability between a small home and the huge outer space. This incommensurability makes Ruzaevka, or any other small place, more noticeable and valuable against the backdrop of “the whole Earth” and the infinite Universe. A space selfie is a good way to draw attention to an unknown point on the map. Ham radio enthusiasts and other such amateur space explorers do not dissolve themselves into planetary humanity or nation, but preserve their sense of home while exploring outer space.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Paige Edmiston.

References

Hecht, Gabrielle. 2018. “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality and Violence”. Cultural Anthropology. 33(1): 109:141. doi: 10.14506/ca33.1.05

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2012. “On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales”. Common Knowledge. 18 (3): 505-524. doi: 10.1215/0961754X-1630424

Olson, Valerie. 2018. Into the Extreme: U.S. Environmental Systems and Politics beyond Earth. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press.

Valentine, David. 2024. “Scales and Futures: Simultaneity, Latency, and Ethics beyond Earth”. Public seminar, UCL University, London, January 10, 2024.