This is a work of hypertext-ethnography.

It is based on my research of a small genetics laboratory in Tokyo, Japan where I am studying the impact of the transnational circulation of scientific materials and practices (including programming) on the production of knowledge. In this piece, I draw primarily from my participant observation field notes along with interviews. I also incorporate other, maybe more atypical, materials such as research papers (mine and others), websites and email.

The timeframe for this work is primarily the spring of 2020 and the setting is largely Zoom. Although I began my research in 2019 physically visiting the lab every week, in April 2020, it—and most of the institute where the lab is located—sent researchers home for seven weeks. That included me. Luckily, the lab quickly resumed its regular weekly meetings online (between the Principal Investigator (PI) and individual post-docs for example, as well as other group planning and educational meetings), and I was invited to join. I continued my ethnography for an additional year in this style.

Working in Zoom, my field notes narrowed to transcript recording, and I eventually grew frustrated with the loss of texture and diversity of information, even hands-on, that I had encountered being in-person, in the lab. However, a good deal of my original field notes from the lab describe scientists working silently and independently at their laptops, and on what kinds of materials or with what tools I could hardly, at the time, fathom. Online meetings allowed me to join scientists, inside their computers in a way, where I had a more intimate access to their experimental work.

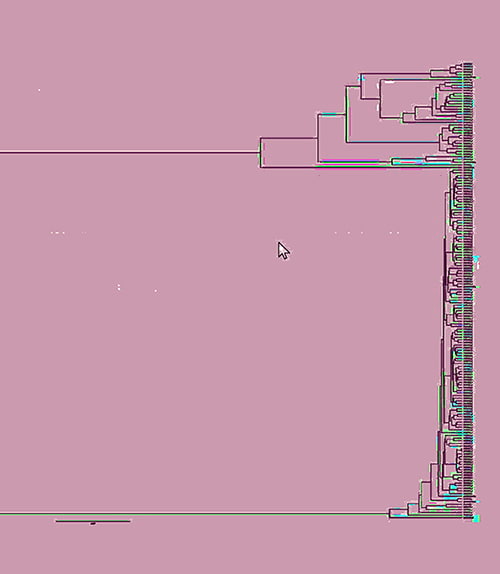

At the same time, the lab was undergoing a transition. Scientists who practiced “wet” experiments (involving human/animal materials in chemical reactions), like many others, were mostly at home and shifting to planning or learning new skills. But even before the pandemic, this laboratory was gradually incorporating more and more “dry” techniques—using computational methods as part of their genetic research. This includes programming languages like Python and R (note that R appears in this work as a literary device more than accurate depiction), and more accessible entry points such as “no-code” and other web-based tools for analysis that require less time-consuming training. More of the researchers began to learn and play with these methods while at home in that time of “slow down,” and with more or less success. While coding scripts are not so completely different from the experimental protocols that scientists use in the lab (each takes time, patience and a kind of careful attention to perfect), they presented a general challenge that was compounded by being separated at home. In my case, just as I felt I was getting a grasp of the technical terms and biological concepts harnessed in the lab’s research projects, I was exposed to, and lost in, a layer of coding practices with which I had no background knowledge. This time of transition, and of destabilization, is ultimately the location of this work. It weaves two threads: a closing down into relative isolation while at home (and a limiting to the kind of surface data I could collect), and a shared opening up to new practices and forms of lab “work,” including computational research (and for me, remote participant observation). This is the experience that I work to recreate here in interactive form.

As a kind of ethnographic accounting, hypertext-ethnography remains uncommon. Despite the promise of early works such as Jay Ruby’s Oak Park Stories (2005) and Rodrick Coover’s Cultures in Webs (2003), hypertextual forms have been mostly left for other disciplines like documentary filmmaking (some examples are described by Favero, 2014). For most, its bare textual form—as in this piece—might even be considered horribly outdated. For me, hypertext is a method to tell a different kind of story. I use this as a form of ethnographic representation along a relatively rhizomatic path to convey the feeling of being “always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1993, 25). Here, interpretation emerges as part of the direction the reader intentionally, or accidentally, takes through the material; it is therefore open in ways different from traditional academic texts. Any “narrative” emerges primarily in juxtaposition of moments, comments, records and links that also refuses complete(d) analysis. At the same time, hypertext highlights the multivocal and always emergent nature of ethnographic data, destabilizing authorship, if even in small ways. It helps me to raise familiar questions which don’t have (any) easy answers: how do we ever know what we know, and how much do we really need to know and understand to faithfully represent others?

For me, this “story” is only one story among many others which I have yet to fully see.

References

Coover, R. (2003). Cultures in webs: Working in hypermedia with the documentary image. CITY: Eastgate Systems.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1993) A thousand plateaus. Minnesota: The University of Minnesota Press.

Droney, D. (2014) “Ironies of laboratory work during Ghana’s second age of optimism.” Cultural Anthropology 29:2, 363-384, https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.2.10

DeSilvey, C. (2006) “Observed decay: Telling stories with mutable things.” Journal of Material Culture 11:3, 318–338, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506068808

Favero, P. (2014) “Learning to look beyond the frame: reflections on the changing meaning of images in the age of digital media practices.” Visual Studies 29:2, 166-179, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2014.887269

Larkin, B. (2008) Signal and noise: Media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

Li N., Jin K., Bai Y., Fu H., Liu L. and B. Liu (2020) “Tn5 transposase applied in genomics research.” Int J Mol Sci. Nov 6;21(21):8329. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218329.

Krasmann, S. (2020) “The logic of the surface: on the epistemology of algorithms in times of big data.” Information, Communication & Society, 23:14, 2096-2109, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1726986

McClintock, B. (1973) Letter from Barbara McClintock to maize geneticist Oliver Nelson.

Pink S., Ruckenstein M., Willim R., and M. Duque (2018) “Broken data: Conceptualising data in an emerging world.” Big Data & Society January–June: 1–13.

Ravindran, S. (2012) “Barbara McClintock and the discovery of jumping genes.” PNAS 109 (50) 20198-20199, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219372109

Ruby, J. (2005) Oak Park stories. Watertown: Documentary Educational Resource.

Venables, W. N., Smith D. M. and the R Core Team (2022) An introduction to R. Notes on R: A programming environment for data analysis and graphics, version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31).

Virilio, P. (1997) Open sky. Translated by J. Rose. London: Verso.

Virilio, P. (1999) Politics of the very worst: An interview by Philippe Petit. Edited by S. Lotringer and translated by M. Cavaliere. New York: Semiotext(e).

Virilio, P. (2000) Polar inertia. Translated by P. Camiller. London: Sage