What does it mean to speak about the cloud? While the term tends to conjure images of fluffy white objects, the cloud in technological terms is a complex physical infrastructure that comprises hundreds of thousands of servers distributed around the globe that provide on-demand access to data storage and computing resources over the internet. The problem with describing this physical infrastructure as the cloud is that it abstracts away the data centers, subsea fiber optic cables, copper lines, and networked devices that enable our digital interactions, as well as the consequences that the expansion of this infrastructure poses to people and to the environment. Scholars of infrastructure have written about the cloud’s incredible energy and water consumption to power and cool servers,[1] as well as its massive carbon footprint (Carruth 2014; Edwards et al. 2024; Hogan 2018; Johnson 2023).[2] However, less attention has been given to the cloud’s auditory presence, a problem of growing concern for people who live alongside cloud infrastructure. In this post, I draw on ethnographic fieldwork that began in 2021 with community activists in Northern Virginia, a place known as the “data center capital of the world,” to bring the cloud’s emerging sound pollution problem into focus.

From the outside, large-scale data centers—the physical and local manifestations of the cloud—appear to passersby as warehouses or factories, though they stand out for the vast amount of land they cover, the enormous cooling systems on their rooftops, and the extensive security measures that are in place, like tall iron perimeter fences and security guards. Data centers are designed to remain operational around the clock and are therefore connected to multiple local utilities; they are a global infrastructure, but one that is sustained by local infrastructures and resources. Inside, towering rows upon rows of racks hold servers layered atop one another, seeming to stretch on forever. The palpable hum of cooling and heat expulsion systems is so loud that technicians must wear ear protection.

These cooling and heat expulsion systems are not only audible to those who work inside data centers to provide an “always on and ready” infrastructure. The noise these systems emit externally is also, increasingly, disturbing for communities that live near large-scale data centers.

Figure 1: Server hall in a “hyperscale” or large-scale data center in Northern Virginia. Image by author.

As an information scientist, I have ethnographically studied data centers for nearly three years. My dissertation work involved interviewing data center industry experts from around the world, government officials, environmental and community activists, proponents and opponents of data center developments, utility providers, municipal planners, and economic development specialists. During my fieldwork, I became especially drawn to ongoing debates about where to locate data centers, like those unfolding in communities that companies have targeted as prime data center sites, especially in Northern Virginia—the field site for my research. To engage with these debates, my participant observation focused on public hearings regarding data center developments, community events and protests, data center bill lobbying sessions, and tours of data centers across Northern Virginia and throughout the United States.[3]

“The Heart of the Internet”

Home to the highest concentration of data centers on the planet, Northern Virginia presents a unique opportunity to study the cloud (Data Center Frontier 2022).[4] Fittingly, the data center industry experts I spoke with often referred to the locale as the “data center capital of the world” or “the heart of the internet.” Northern Virginia stands out to data center developers for its extensive fiber connectivity, tax breaks on computing equipment, rural land, and stable natural environment. Nearby, Virginia Beach hosts the first transoceanic fiber cable connection points in the mid-Atlantic. The proximity to the federal government and to Washington D.C. offers added security benefits with a strong U.S. military presence.

Many municipalities and public officials across Northern Virginia lobby the interests of data center developers for the promise of the tremendous tax revenue they tend to generate for public services and for local employment opportunities. For rural communities, data centers also often represent the ability to control what is perceived to be inevitable urbanization.

The cloud, however, is not without its detractors. Local community activists have started to resist the expansion of data centers due to the strain they place on local energy and water infrastructure, the costs to build out the infrastructure necessary to support data centers, and the sheer size and scale of data center developments. Despite the cloud’s perceived immateriality, communities across Northern Virginia experience this infrastructure in very material ways. They invoke their everyday encounters with data centers to question the perceived benefits of locating the cloud in their community. In my discussion to follow, I explore the role of community activists in making the cloud’s auditory presence known in Prince William County, Northern Virginia.

The Cloud is Loud

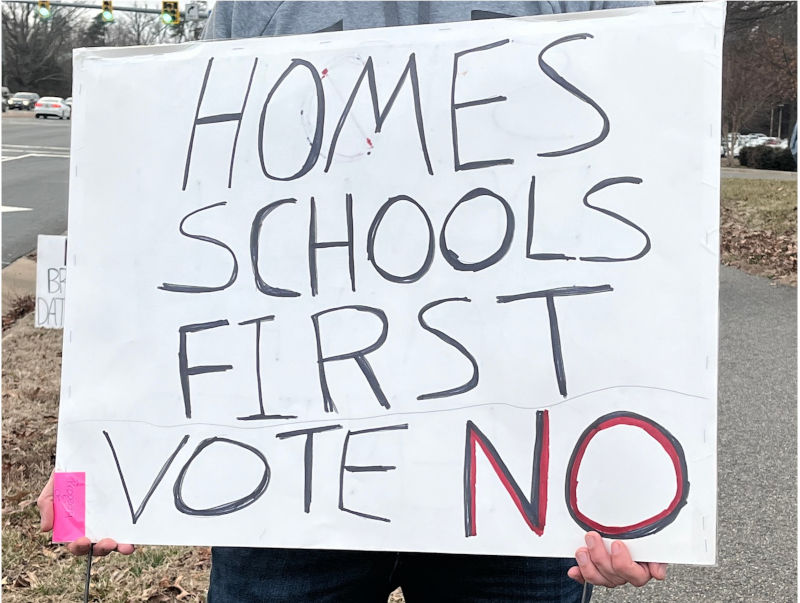

In the spring of 2023, while attending a data center protest, I met Nicole and her teenage son Jacob, standing out front of the county administrative center holding a large poster board that read “Homes/schools first. Vote no.” Nicole and Jacob’s activism and that of many of their neighbors is largely driven by the daily disturbances and discomforts posed by the noise that data centers emit. Nicole and her family first became aware of the Amazon data center roughly a quarter mile from their home when construction workers began blasting through bedrock, but now, she explained, they “have to listen to the awful sounds of the thing [the data center] actually running. It never stops.”

Figure 2: Jacob holds a posterboard out front of the county administrative center in Woodbridge, Prince William County, VA during a data center protest.

Jacob’s poster reads: “Homes/schools first. Vote no.” Image by author.

Many of my informants—some who live within just 600 feet of a data center—shared similar cautionary tales. Viviane explained that “it’s just a constant humming and buzzing noise. It’s driving me insane. I sleep with headphones on and listen to quiet music to drown it out—ear plugs aren’t enough.” Martha no longer enjoys tending her garden because it’s like she “lives next to a busy highway now.” Tony, whose townhome once overlooked a grassy hillside, suggests that “once you notice it [the noise], it’s impossible to find relief.” Christopher regularly attends county board meetings to urge the board to “pass a modern-day noise ordinance.”

The “awful sounds” of the data center are generated by the cooling systems that sit atop their roofs and the diesel generators on the periphery of the buildings. The cooling systems are not traditional HVAC systems that most people are likely familiar with. They are significantly larger and louder than residential cooling systems and sit atop buildings that are in many cases four stories tall. Data centers are high-density enclosed spaces that generate tremendous amounts of heat which must be quickly removed to protect the delicate servers. My interviews with engineers revealed that heat densities in a typical data center environment can be up to five times higher than in a typical office setting. The primary backup power source for data centers, diesel generators, must be tested regularly to ensure operability. These generators are quite literally the size of tractor-trailers, emitting noise akin to city traffic or a jet engine passing overhead. In addition, unlike other kinds of industrial developments, data center noise is largely unregulated. Many local noise ordinances do not account for cooling systems on rooftops, which are standard designs for large-scale data centers.

Figure 3: Large-scale data center in Northern Virginia under construction. The data center’s massive cooling systems can be seen on the roof of the building. Image by author.

Making Their Own Kind of Noise

In hopes of influencing local noise ordinances, community activists have taken on the task of conducting noise studies using professional equipment. Their studies reveal that although data centers often do operate within the decibel ranges identified by the county for residential areas (60 decibels during the daytime and 55 decibels at night), they also tend to exceed those ranges, particularly on hot days and nights. Michael, a former engineer leading the noise study efforts, explained that noise studies often rely on an average of sound levels. In this case, he argues that averages fail to account for times when data centers are operating above appropriate decibel levels, and also fail to account for how people actually experience the noise. In other words, he suggests that “it’s not necessarily that data center cooling systems have incredibly high decibel ratings—though the generators do—it’s that they emit noise nearly constantly.”

Community members and public officials who advocate for the expansion of data centers locally—often citing the potential for tax revenue—liken data center noise to “an environmentalists’ fantasy,” or no more significant than “mating crickets and existing road noise.” However, noise pollution, and diesel generators in particular, have well-documented impacts to mental and physical health, including insomnia, increased cortisol levels, mood changes, and hearing loss, among others (Bronzaft 2017; Hammer et al. 2014; Mohammed & Rabeea 2021). Data center noise is an especially understudied form of industrial noise.

By making their own kind of noise—filing noise pollution violations—my informants are engaging in what I consider to be an important form of activism and community-based knowledge production, or “citizen science,” as many environmental justice scholars term it (Ottinger, 2010). Ottinger (2010) defines citizen science as the process of producing knowledge “by, and for, nonscientists” to contribute to environmental decision-making and to produce more robust and democratic policies (Fischer 2000; Irwin 2001; Ottinger 2010). It also aims to influence the research directions of science to be “more responsive to broad social concerns” (Hess 2007; Martin 2006). The cloud’s auditory presence is not yet widely recognized or effectively accounted for with appropriate policies. The notion that my informants conducted a noise study at all suggests something important: the need to substantiate the everyday material realities of the cloud to shape the expansion and governance of this infrastructure.

Communities across Northern Virginia are beginning to challenge how we think about the cloud. Although Northern Virginia is considered the cloud’s epicenter, the effects of its growth are no longer confined to this area (Dance 2024; Pineda 2021; Pogue 2024). The cloud must go somewhere, but by attending to its materiality, I hope to contribute a deeper understanding of the consequences of our data growth and especially to highlight the critical voices and community perspectives of cloud growth. When we consider these perspectives, we can begin to grapple with the consequences of an infrastructure that is in reality not very cloud-like at all but is instead inseparably tied to the environment, natural resources, other infrastructures, and communities of people.

Notes

[1] Data centers in the U.S consume an average of 300,000 gallons of water daily to cool servers (Copley 2022). In 2022, data centers consumed over four percent of the nation’s electricity (International Energy Agency 2024).

[2] The carbon footprint of the cloud has surpassed the airline industry. See The Shift Project (2019): https://theshiftproject.org/en/article/unsustainable-use-online-video/

[3] I also conducted policy and document analysis of community and industry media coverage, data center industry documents and reports, government documents and reports, and policies regarding data centers.

[4] See also: Virginia Economic Development Partnership https://www.vedp.org/industry/data-centers

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all those that have contributed to my dissertation work, especially my informants. I am so thankful to Paige Edmiston and Jessica Olivares for their feedback and guidance on this post!

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Paige Edmiston.

References

Bronzaft, Arline. L. 2017. “Impact of Noise on Health: The Divide between Policy and Science.” Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5(5): 108-120. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2017.55008

Carruth, Allison. 2014. “The Digital Cloud and the Micropolitics of Energy.” Public Culture, 26(2), 339–364. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2392093

Dance, Gabriel J. X. 2024. “Anxiety, Mood Swings and Sleepless Nights: Life Near a Bitcoin Mine—The New York Times.” https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/03/us/bitcoin-arkansas-noise-pollution.html

Data Center Frontier. 2022. “The Home of the Cloud: Rapid Growth Continues in Northern Virginia.” Data Center Frontier. https://www.datacenterfrontier.com/special-reports/article/11427277/the-home-of-the-cloud-rapid-growth-continues-in-northern-virginia

Edwards, Dustin., Cooper, Zane. G. T., & Hogan, Mél. 2024. “The making of critical data center studies.” Convergence, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231224157

Copley, Michael. 2022. “Data Centers, backbone of the digital economy, face water scarcity and climate risk .” https://www.npr.org/2022/08/30/1119938708/data-centers-backbone-of-the-digital-economy-face-water-scarcity-and-climate-ris

Fischer, Frank. 2000. “Citizens, Experts, and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge.” Duke University Press.

Hammer, Monica. S., Swinburn, Tracy. K., & Neitzel, Richard. L. 2014. “Environmental Noise Pollution in the United States: Developing an Effective Public Health Response.” Environmental Health Perspectives, 122(2), 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307272

Hess, David. J. 2007. “Alternative Pathways in Science and Industry: Activism, Innovation, and the Environment in an Era of Globalizaztion.” MIT Press.

Hogan, Mél. 2018. “Big data ecologies.” Ephemera Theory and Politics in Organization, 18.3, 631–657.

International Energy Agency. (2024). “Electricity 2024—Analysis and forecast to 2026.” https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/6b2fd954-2017-408e-bf08 952fdd62118a/Electricity2024-Analysisandforecastto2026.pdf

Irwin, Alan. 2001. “Constructing the scientific citizen: Science and democracy in the biosciences.” Public Understanding of Science, 10(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3109/a036852

Johnson, Alix. 2023. “Where Cloud Is Ground: Placing Data and Making Place in Iceland.” University of California Press.

Martin, Brian. 2006. Strategies for Alternative Science. https://documents.uow.edu.au/~bmartin/pubs/06Frickel.html

Mohammed, Mahmmoud., & Rabeea, Muwafaq. 2021. “Effects of Noise Pollution from Electric Backup Generators on the Operators’ Health.” Pertanika Journal of Science and Technology, 29. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjst.29.4.24

Ottinger, Gwen. 2010. “Buckets of Resistance: Standards and the Effectiveness of Citizen Science.” Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35(2), 244–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243909337121

Pineda, Paulina. 2021. “Unsustainable, resource-hungry and loud: Why Chandler wants to ban more data centers.” The Arizona Republic. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/chandler/2021/11/22/chandler-wants-ban-more-data-centers-after-years-complaints/8627569002/

Pogue, David. 2024. “Cryptocurrency is making lots of noise, literally.” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bitcoin-noise-arkansas-right-to-mine-bill/