Menstruation as a subject of study is not new. Margaret Mead, Mary Douglas, Chris Bobel, Miren Guillo, and Karina Felitti, among many others, have discussed how menstruation has been related to specific practices, and how taboos present great dynamism and variability as specific cultural constructions frequently linked to systems of bodily control and gender.

In this post, I present research that explores how taboos associated with menstruation are reflected in the bodily and emotional trajectory of menstruating women and people through the implementation of a methodology based on the collective construction of emotional corpobiographies (Ramírez, 2024). Although the relationship between taboo and shame around menstruation has been widely documented from various scientific and theoretical perspectives, this research seeks to delve into the moments, key actors, and narratives that make emotions and attitudes become embodied and acquire deep meaning in the menstrual experience. The study focuses on the trajectory of university women in Guadalajara, Mexico, and is a qualitative analysis that builds upon the results of the “Fluye con seguridad” survey, conducted in 2023 in the University of Guadalajara network.

Feminisms, Activisms, and Menstrual Education

From a hegemonic reading, the second and third waves of feminism were decisive in positioning menstruation as a fundamental part of the feminist agenda. In Latin America, activism and menstrual education emerge as two movements that, despite their internal tensions, form action-research projects oriented towards health and rights (Calafell, 2021). These movements, which have consolidated in the last decade, have created spaces for dissemination, information, and political action through territorial work and digital presence. The latter has been especially significant not only for questioning taboos, historical shame, and gender biases associated with menstruation, but also for its commitment to building scientifically grounded, experiential, inclusive, and diverse content. This approach considers bodily diversity, gender, race, sexual orientation diversity, and cultural variations in the construction of bodies and technologies for their management (in this case menstrual), allowing women and menstruating people or those who are about to menstruate to access meaningful information that transcends mere exposure to content on digital platforms.

Quantitative Background of the Exploration

The “Fluye con seguridad” survey (Muñiz, Ramírez, Sánchez, Garibaldi, García, Romero & Reynoso, 2024), conducted at the University of Guadalajara, allowed us to construct a situated panorama of knowledge about menstruation in the university population. It was a representative exercise, with a sample of 2,741 cases, and is the first inter-university survey of its kind. I share here two central points that gave rise to this qualitative exploration. For the population of women and menstruating people at the university:

- Menstruation is visibilized through stigma and silencing, to the extent that it is preferable to use euphemisms (more than 130 different ones were recorded) instead of the word menstruation.

- Four governing emotions are identified: shame 57%, fear 46%, disgust 30%, and rejection 21%. These emotions not only affect the perception of menstruation but also impact broader aspects, such as the desire not to menstruate (78%), feelings of hate (55%), or rejection towards being a woman (50%).

Glimpses into Emotional Corpobiographies about Shame

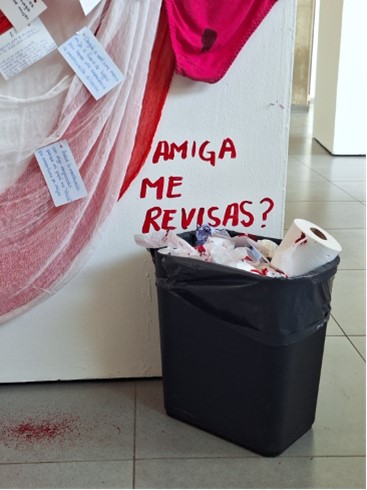

“Amiga ¿me avisas?” Original photo by Rosario Ramírez[1]

“Amiga ¿me avisas?” Original photo by Rosario Ramírez[1]

Shame is “caused by the attention that third parties exercise on our bodily manifestation” (Simmel, 2018:70) and is a link that reveals the relationship with others and with oneself from the gaze of the other (Sabido, 2020:301), but always situated and constructed from relational and emotional contexts. When recovering the emotional corpobiographies of university women, it is observed that the lack of information about what menstruation is, what it implies, and how it feels, as well as secrecy and moral and religious discourses around the body, were determining factors for the experience of menarche to be wrapped in surprise and confusion, but not necessarily rejection.

The rejection around menarche is mainly related to social factors and comments like “you’re a woman now” or “you’re a young lady,” and to the norms and stereotypes associated with femininity that set aside childhood-centered experience, especially in the case of early menarche. The experience of menstruating, while seemingly individual, continues to be an event with social and normative character that directs and potentially conditions experiences, emotions, identifications, and belongings: “I menstruated at 8, and it was very strong because I didn’t want to be a woman, I wanted to continue being a girl. I feel they took away my right to live my childhood.” “I menstruated at 15, and that made me feel that now I was really part of women.” “I remember that when I told people in my circle, they made me feel superior because I was developing faster than others, I was already a woman.”

This factor of menstruation socialization also generates contradictory emotions and experiences. Mothers (and sisters, in some cases) tend to be the main references and the first people in circles of trust. However, the perception of the information they receive from them is not adequate or sufficient, and in most cases, there is no feeling of accompaniment in the experience of menstruating. In extended circles is where the construction of taboo and the incorporation of shame are most identified, as comments from brothers, friends, uncles, or other men create differentiated valuations. In cases of apparently positive valuation, menstruation is constructed based on its reproductive potential, and on a heteronormative representation of potential social and family relationships (“now you can get married”). This is uncomfortable because it touches on reproductive or relational decisions that have to do with the bodily and sexual autonomy of women and menstruating people.

On the other hand, those narratives that associate menstruation with a natural process also reproduce other invisibilization discourses: “menstruating is so natural that it wasn’t worth talking about,” or reproduce the notion of blood as waste and as a contaminating fluid that should generate disgust if seen or named publicly. Examples of this are stories associated with stains, particularly in the first years of the menstrual trajectory: “I went to church with my mom and was wearing white, I stained myself a lot and everyone’s looks made me feel ashamed.”

A fundamental factor that significantly changes the perception of menstrual experience is peer socialization, particularly in adulthood. Sharing experiences and embodied emotions around the menstrual trajectory has been a fundamental element in facing taboo and transforming shame. It stands out that menstruation in the context of adulthood nuances emotions of rejection and disgust, mainly because there is more openness to talk about the body, and due to the appropriation of feminist discourses and narratives that center on autonomy, bodily pedagogies, self-care, and collective care. There is also less perceived social demand and greater openness to experimentation associated with sexual relations during menstruation or with the use of management alternatives such as menstrual cups, menstrual discs, or free bleeding.

In this sense, digital platforms have played a fundamental role: they have functioned as spaces for denunciation, where users make visible the scarcity of information about menstrual health, transforming shame into embodied experiences and knowledge. And these platforms have also been crucial in the dissemination of menstrual management alternatives, transcending their role as mere marketing tools to become spaces for constructing bodily and menstrual pedagogies that bet on education and health from autonomy.

Provisional Conclusions

The menstrual experience is configured as a complex phenomenon where social, cultural, technological, and emotional factors converge to shape its individual and collective experience. Shame emerges as a structuring emotion that not only affects how menstruation is perceived and embodied but also reveals the tensions between intimate bodily experience and its social dimension. This emotion, far from being merely individual, is constructed through the gaze of the other and social norms, as evidenced by testimonies about menarche and its implications in the identity construction of “being a woman.”

Here we see three significant transformations in contemporary menstrual experience: first, the transition from an experience marked by silence and misinformation towards spaces of dialogue and collective construction of knowledge; second, the crucial role of adult peer socialization as a factor of resignification and resistance to traditional taboos; and third, the emergence of digital platforms as spaces that not only make visible and denounce the lack of information but actively construct new bodily and menstrual pedagogies.

While moral, religious, and gender discourses that have historically conditioned menstrual valuation and experience persist, a transformation process is observed, driven by two main forces: the agency of women and menstruating people seeking to resignify their bodily and emotional processes; and the creation of digital content that politicizes the menstrual experience and proposes new forms of representation and menstrual education from autonomy.

This research opens the way to deepen how taboo operates at different levels of menstrual experience, suggesting the need to continue exploring the intersection between bodily-emotional experience and contemporary socio-digital contexts. Particularly, it is relevant to analyze how new forms of digital socialization are reconfiguring narratives about menstruation and transforming shame into a motor of social and political change.

Note

[1] Research Professor. Department of Sociology at Universidad de Guadalajara, México. mros.rm@gmail.com and rosario.rmorales@academicos.udg.mx – https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria-Del-Rosario-Ramirez-Morales/research

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Iván Flores.

References

Calafell Sala, N. (2021). La educación menstrual como proyecto feminista de investigación/acción. Revista Pedagógica, 23, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.22196/rp.v22i0.6500

Muñiz, S., Ramírez, R., Sánchez, A. M., Garibaldi, E., García, Z., Romero, F., & Reynoso, M. (2024). Encuesta Universitaria de Menstruación “Fluye con Seguridad”. Universidad de Guadalajara: FEU, CEG CEED. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380785862_Encuesta_Universitaria_sobre_Menstruacion_Fluye_con_Seguridad

Sabido, O. (2020). La vergüenza desde una perspectiva relacional. La propuesta de Georg Simmel y sus rendimientos teórico-metodológicos. En Ariza, M. (Eds.)editor. Las emociones en la vida social : miradas sociológicas (pp. 293-325). IIS UNAM.

Simmel, Georg (2018). “Sobre una psicología de la vergüenza”. Digithum 21:67-74.

Ramírez, R. (2024). Aproximaciones al cuerpo y las emociones alrededor de la experiencia menstrual [presentation]. Mexico City, Mexico.