Note: This post contains images of skin wounds. If you are dermatophobic, read/view at your own discretion. You may instead listen to the post.

An entry into the world through the pore urges us to see the chemical and material world as vital, volatile, viscous, transcorporeal–some of the topics addressed in the Platypus series, “Witnessing the porous world.” Jane Bennett, in describing and diving into the “life of metal,” begins by asking, “can nonorganic bodies also have a life? Can materiality itself be vital?” (2009, 53). Life, for Bennett as they converse with philosophers Deleuze and Nietzsche is, “a-subjective” and “impersonal” (54). Bennett’s effort to “avoid anthropocentrism and biocentrism”, leads them to “material” and “metallic vitality” that is imminent from “vacancies,” “holes,” and “cracks” that render material “porous” (59-61).

Pores, since they compose many materials from soil to cement are ubiquitous and enable the vitality of the inorganic world. But when vitalities, immanent from pore, produce death like conditions, should our “metaphors” for describing the materiality of inorganic world “matter,” like vitality differently (Hecht 2018, 112)? In other words, what frameworks can express the chemical vitalities that emerge from and through pores, without compromising on its deadliness and counting in exclusions? This piece offers one such framework, namely necrovitalities which is characterized by a constant “inversion between life and death,” that is constituted and made visible through the pores that compose the material world (Mbembe 2019). For this, we enter the world around Tummalapalle Uranium Mine and Mill’s tailing pond with pores as portal.

A satellite image of the topography of the landscape around Tummalapalle Uranium Mine and Mill’s tailing pond| Source: Google Earth

Mabbuchintalapalle, Kottala and Kannampalli are villages located around the Tummalapalle Uranium Mine and Mill’s (TUMM) tailing pond in Andhra Pradesh, India. Tailing ponds are technologies of impoundment that contain waste from chemical processing in industries within its structure. Both pollution control and nuclear regulatory authorities recommend lining the tailing pond with natural and geo-membrane liners of varied porosities to make the bed of the tailing pond impermeable so that radioactive effluents are contained within the pond. Be they natural liners materials that have high porosity (like clay that has more number of pores between its particles) or geo-membranes with lowest porosity (like polyethylene sheet), liners effectuate (im-)permeability. Impoundment in this way is actualized in its relation to porosity, as pores in the lining material shape the tortuous pathways that chemicals take as they permeate underground.

The Uranium Corporation of India Limited (UCIL), a public sector undertaking that manages TUMM, followed the nuclear safety guidelines stipulated by the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) and laid a clay lining with a permeability between 0.0000001 and 0.000000001 meters per second (AERB 2007). However, it did not line the tailing pond with an impermeable liner like polyethylene layer that has extremely low pores–a condition laid down by the Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board. Since AERB’s recommendation on clay lining helped it attain the “desired permeability” i.e. 0.000000001 meters per second according to nuclear safety guidelines, UCIL did not find it necessary to line the tailing pond with polyethylene liner as “an extra-precautionary measure” (UCIL 2018). As I have written elsewhere (Shaik Ali 2024), UCIL adopted practices of divisible governance (Howey and Neale 2022) by fragmenting nuclear regulatory jurisdictions from that of pollution control.

A farmer showing soil and rocks abraded by contaminated water. Image captured by author in October 2021.

Farmers and residents first sensed the contamination as the underground water that they drew from their agricultural borewells turned white. They claim that the tailings have permeated the underground and had contaminated aquifers. Drip pipes clogged with chemical particles impeding the flow of water from the underground onto the farms has led to farmers using abrasive chemicals to clear the holes on the drip pipe.

Drip pipe with white chemical sedimentation around drip holes. Image taken by author in October 2021

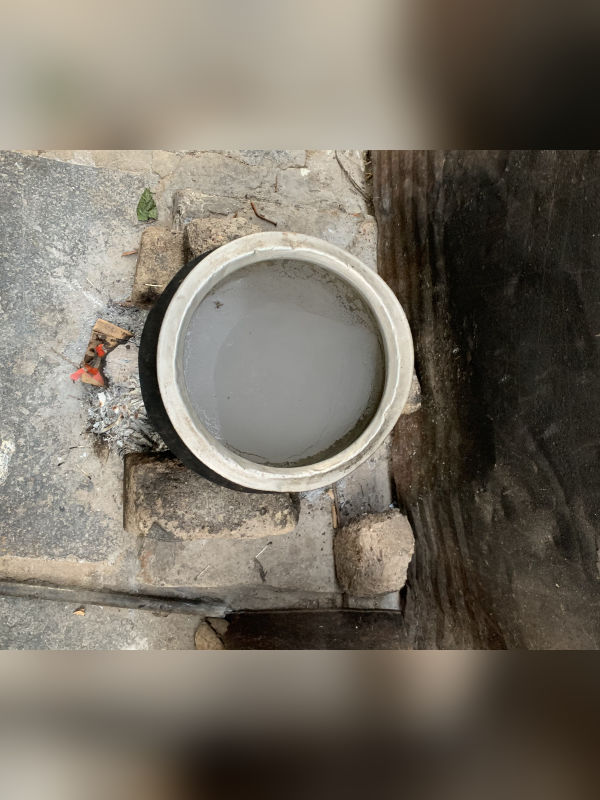

Village residents who used to boil water every evening for consumption purposes, now do it to display the chemicals sedimentation and saturation in water to journalists, anthropologists, and fact finding teams.

Water being boiled in Mabbuchintalapalle. Image taken by author in Oct 2021.

As I walked down what is being referred to as Scheduled Caste colony[1] road in Mabbuchintalapalle village in 2021, residents were heating water and called out to me to show how layers of chemicals settle to the bottom of their aluminium pot. One woman scratched the inner surface of the pot hard to crack a tiny bit of the chemical sediments that had saturated at the bottom and to show me the hardness of the water they use. She cut her skin while scratching out the saturated sediment. I gasped and said, “I told you not to break it, now look your hand is cut.” She replied, “Aaaaannn” (that’s okay),” sighing she added, “We want you to see.” But I could not stop thinking that in the process, she has exposed herself to those chemicals more closely, more vividly. I could not stop worrying about what these ‘vital’ chemicals could do to her as they entered her cracked skin.

Saturated and hardened piece of the water in chemicals on the palm of an participant. The thump nail has been chipped, exposing wound. Image taken by author in Oct 2021.

While I was concerned about the injury on her skin, her insistence to peel off saturated chemicals for me to see and witness, was an emphasis that her skin, as it is composed of pores, does not end at her body (Stacey and Ahmad 2001). Instead, the pores on her skin connect to the tortuous pathways chemicals take through the pores composed by clay particles on UCIL’s clay liners. In this way, pathways composed by pores shape the exposure pathways of industrial effluents, entering bodies of women who use water for domestic chores more. In this way, their skin remains more porous than men who do lesser domestic chores.

Walking down these exposure pathways, I arrived at the temple where I was supposed to meet Mabbuchintalapalle’s women facing menstrual health issues including 28 days-long periods, painful menstruation, spontaneous abortions, involuntary childlessness and prenatal issues like fetal anomalies (Shaik Ali 2024). As I exited the temple after a three-hour focused group discussion and stepped back onto the road, one of my interlocutors brought a former temporary worker at TUMM and showed his feet to me. “Look at his feet. This is because of working in the mill ma’am.” I replied, “Do they not give protective equipment in the mill?” He replied, “No ma’am.” I took a photograph of his feet and went back to the hotel to rest after an over-stimulating ethnographic day.

The wounded feet of a former non-permanent worker. Image taken by author in Oct 2021.

A couple of days later, a man stopped my interlocutor and me while we were on a bike on our way to Kottala. My interlocutor introduced him to me as a permanent employee at UCIL and we began talking about my research. Knowing his position and to be safe during my field visit, I soothed my anti-nuclear temper and stated, “From what I hear, everything seems to be safe in the plant itself. It is only the tailing pond that seems to be causing an issue.” He smirked and asked me to wait as he took his phone out of his pocket. He opened a photograph showing three feet around a drum, exposed to yellow dust and added, “Those are workers’ legs exposed to yellow cake as they were canning it.”

Shocked, I replied, “Shouldn’t the mill be automated? Why are workers doing this job? Wouldn’t their radiation exposure be recorded by occupational safety devices?” He said, “Yeah, our TLD (Thermo-luminescent Dosimeters) badges would show exposure but only permanent workers are given TLD badges. These are contract workers who are made to enter radioactive spaces without badges.” TLD badges change colour based on the intensity of exposure and AERB collects these badges from the facility to check if radiation workers are safe at work. Since temporary contract workers are non-radiation workers, like the worker I met at Scheduled Caste colony, they are not mandated to wear these TLD badges. To show compliance, UCIL has made temporary workers enter radioactive spaces that risk exposure so that their permanent employees’ badges over limits.

UCIL recruits mostly non-radiation workers, and engineering graduates from the local area as permanent employees. This is to fulfil their much touted claim that UCIL plants generate local employment. However, in Tummalapalle, UCIL offered permanent employment as compensation to the land-owning class or their family members from whom it had acquired land. This means, non-land-owning class or agricultural labourers who worked on UCIL acquired farms would not get permanent employment at UCIL and due to UCIL’s acquisition, lost employment in the farms they worked on.

Since permanent employment comes with medical insurance, most of the residents now want UCIL to acquire the contaminated land beneath their residences and farms and become “land losers” so that they can at least access medical insurance. This, they believe, will help them in getting the necessary treatment for contamination related-illnesses like kidney and liver issues, fertility concerns, congenital anomalies, cancer, dermatitis, to name a few. The exposure pathway of the contamination at TUMM, begins between the pores of the clay lining, pierces through the pores composing skin and ends in organs and flesh, providing home for material vitality of chemicals. The woman’s skin and the ex-temporary workers’ feet conveyed to me that pores are non-innocent entities and as caste and class relations structure their materiality, they exclude the gendered, casteized and working class bodies. Pores connect partially.

With no hope that the State will protect people’s right to health, residents in Mabbuchintalapalle, Kottala and Kannampalli rest their hope for living and life in death generating conditions. By ignoring, first, the Indian nuclear state exercised its sovereignty in the “power and capacity to dictate who is able to live and who must die.” This has been considered as the crux of what Mbembe (2017) called necropolitics. Perplexed by the necropolitical conditions and forced displacement, I asked these aspiring land-losers, “When you know things are not that safe in the plant, why do you want to work there? Wouldn’t it affect your body?” The first person I had asked this question during my October 2021 fieldwork had just utilized his insurance towards treating congenital conditions of his new-born child. He replied, “It is only the tailing pond that is creating the problem. Everything is safe in the plant itself.”

The second person I had asked this question during my June 2025 fieldwork, was not yet a permanent employee and is leading the movement in Kottala to urge UCIL to acquire the entire village, make villagers “landlosers” and in return, provide monetary and employment compensation to all. He replied, “Our lives are over living in these conditions. At least our children will benefit from the compensation and insurance.” By “these conditions,” he meant the chemical contamination conditions where compensations dually afford death and sustains life, living and vitalities. Here, to be injured is a way to sustain life (Petryna 2004; Cram 2024). The third person I asked the question about the plant’s safety is a permanent employee, “We can’t ask the mine to shut down ma’am. India needs [nuclear] bombs in case of wars like Pahalgam against Pakistan. We need TUMM. So, we will get the money and get on our way. They may continue.”

Achille Mbembe (2017) has also pointed out how living constitutes death in the conceptualization of necropolitics. Here, “life” is “merely death’s medium” (38) and in choosing death, “body” attains “its power and value” in its “desire for eternity” (89). This is because, for “self-sacrificers,” “this power may be derived from the belief that destroying one’s own body does not affect the continuity of being” (90). The desire for eternity reverberates in the words of my second respondent: “At least, our children will benefit.” While the body serves as evidence to speak about milling waste entering the social through multiple pores on clay lining, the body (and the harm it embodies) becomes absent in necropolitical “inversion between life and death.”

As chemicals pass through pores that compose environmental pathways, chemicals are neither “lively,” nor “vibrant,” as Hecht (2018, 112) states– the “metaphors” scholars use to describe the materiality of deadly chemicals “matter”. The vitality of chemicals instead enmeshes with necropolitical conditions, bloated with inversions between life and death, and chemicals become necro-vital sources. Necrovitality gives meaning to living and dying in chemical conditions. When the vitality of toxins intersects with death worlds, “new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the living dead” emerge (Mbembe 2019, 92). Hence, necrovitality becomes an inescapable late-industrial condition where death and deadly things sustain possibilities of life and living. Necrovitality as a phenomena is ubiquitous as pores are in the extractivist, capitalist and neo-liberal ways of living that orders today’s existence.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Misria Shaik Ali and reviewed by Contributing Editor Sumitra Nair. Special thanks to Sumitra Nair for reading the post and to Lee Nelson for conversations on the concept of necro-vitality.

Notes

[1] In the states of Andhra and Tamil Nadu, reserved lands allotted for Dalits are colloquially referred to as a scheduled caste colony. In Tamil Nadu the government has stopped referring to such Dalit Settlements as “colony” as “colony” is considered derogatory compounding the discrimination against Dalits in the states. See Madhav (2025).

References

AERB (Atomic Energy Regulatory Board) . 2007. Radiological Safety in Uranium Mining and Milling Safety Guidelines No. AERB/FE/FCF/SG-2. Mumbai, MH: AERB. Accessed November 2, 2024. https://www. aerb.gov.in/images/PDF/CodesGuides/NuclearFacility/FuelCycleFacilities/4.pdf.

Ahmed, Sara and Jackie Stacey. 2001. Thinking through the Skin. London: Routledge.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cram, Shannon. 2023. Unmaking the Bomb: Environmental Cleanup and the Politics of Impossibility. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hecht, Gabrielle. 2018. “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence.” Cultural Anthropology 33 (1): 109–141. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca33.1.05.

Howey, Kirsty, and Timothy Neale. 2022. “Divisible Governance: Making Gas-Fired Futures during Climate Collapse in Northern Australia.” Science, Technology & Human Values 20 (10): 1–30.

Madhav, Pramod. 2025. “MK Stalin to drop ‘colony’ from official use for Dalit settlements in Tamil Nadu.” India Today, April 29. Accessed on October 5, 2025. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/tamil-nadu/story/tn-cm-mk-stalin-to-remove-colony-word-from-official-use-for-dalit-settlements-cites-caste-oppression-2716893-2025-04-29

Mbembe, Achille. 2019. Necropolitics. Duke University Press.

Petryna, Adriana. 2004. Biological Citizenship: The Science and Politics of Chernobyl Exposed Populations. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shaik Ali, Misria. 2024. “The Alterlife of Disable Fetal Imaginary: Understanding Irradiation and Disability after New Reproductive Technologies,” In Medical Technology and the Social: How Medical Technology Is Impacting Social Relations, Institutions, and Beliefs about What Is Normal, edited by Katheryn Burrows. Lexington Books.

UCIL (Uranium Corporation of India Limited). 2018. UCIL’s Responses to Show-cause Notice and APPCB’s observations. Lr. No. 90/APPCB/ZO/KNL/2018.” Kurnool, AP: APPCB, April 19. Srinath Reddy Personal Archives, Pulivendula, AP.