*A note from Co-PI Noopur Raval: The arrival and rise of gig-work globally has ushered in a new wave of conversations around the casualization of labor and the precarious nature of digitally-mediated “gigs,” ranging from online crowdwork gigs to digitally-mediated physical work such as Ubering. Gradually, scholarship has extended beyond North America and Europe to map the landscape of digital labor in the global south. These posts that make up “India’s Gig-Work Economy” are the result of one such project titled ‘Mapping Digital Labour in India,’ where four research fellows and a program manager, me, have been studying the dynamics of app-based ridehailing and food-delivery work in two Indian cities (Mumbai and New Delhi). This project is supported by the Azim Premji University’s Research Grants program. In this series of posts, the research fellows and I offer reflections on pleasure, surveillance, morality and other aspects woven into the sociality of gig-work and consumption in India. Each post also has an accompanying audio piece in an Indian language, in a bid to reach out to non-academic and non-English speaking audiences. The series ends with a roundtable discussion post on the challenges, gender and class dynamics, and ethics of researching gig-work(ers) in India.*

Download a transcript of the audio in Devanagari.

Mumbai, India’s financial capital, is also often considered one of the safest cities for women in India, especially in contrast with New Delhi which is infamously dubbed as the “rape capital” within the country. Sensationalised incidents of harassment, molestation and rape serve as anecdotal references and warnings to other women who dare to venture out alone even during the daytime. The Delhi government recently proposed a policy for free transport for women in public buses and metro trains with the objective of increasing women’s affordability and access and to ensure safety in public transportation.[1] Despite such measures to increase women’s visibility and claims to public utilities and spaces, women who use public transport have historically suffered groping and stalking on buses and trains, which uphold self-policing and surveillance narratives. The issue of women’s safety in India remains a priority as well as a good rhetorical claim and goal to aspire to, for public and private initiatives. Ironically, the notion of women’s safety is also advanced to increase moral policing and censure women’s access to public spaces, which also perpetuates exclusion of other marginalised citizens (Phadke 2007). Further, and crucially, whose safety is being imagined, prioritized and designed for (which class of women are central to the imagination of the safety discourse) is often a point of contention.

In this context, ridehailing services offered by Uber and Ola have come to be frequently cited as safer and more reliable options for women to traverse the cityspace, compared to overcrowded buses and trains. Their mobile applications promise accountability and traceability, enforcing safety standards by way of qualified and well-groomed drivers, SOS buttons and location-sharing features. However, it has increasingly become common knowledge that these alternatives are prone to similar, if not worse, categories of crimes against women. While reports of violence against women in cabs have mostly been outside of Mumbai, due to “platform-effects,” such incidents have widespread ramifications for drivers across the country. Cab drivers who operate via cab aggregator platforms have come under heavy scrutiny not only by the corporate and legal infrastructures of aggregator companies but also in the public eye. On the other hand, platform companies independently, and in partnership with city and state administrations, continue to launch “social impact” initiatives aimed at women’s safety as well as employment (through taxi-driving training).[2] Incidents of violence against women present jarring narratives of risk not only for female passengers but also for the platform-workers, both of whom are responsible for abiding by the constructed notions of safety for women in urban spaces.

In this post, I explore women’s presence as workers as well as passengers/customers in the ridehailing platform economy, in the context of women’s safety, situating the analysis with a focus on Mumbai. The related discourses around risk for female commuters give rise to various interventions and women-centric services through female-only cab enterprises and training more women drivers to mitigate this risk. Through these, I will think through the figure of the woman in the ridehailing economy in Mumbai and by extension in India.

Platforms in Gendered Cityscapes

Mumbai’s public transport is comprised of the local train network, BEST buses and auto rickshaws, with the metro being the newest addition to the mix. Unlike in most of India, kaali-peelis (black-yellow cabs) have been a permanent feature of Mumbai’s landscape since the 1950s and, taking a cab is not necessarily a luxury. Against this backdrop, platform companies have sought to make the claims of democratizing public transport and providing safer travel options to women in the city.

Cab drivers on ridehailing platforms in Mumbai are usually domestic male migrants or Muslim drivers from within and outside the city, who are more often than not overworked and stressed due to the falling incomes and rising debts. It is important to recognise the ‘veiled masculinities’ (Chopra 2006) which labor to service the emergent platform economy and the hierarchies of caste and class which are sustained through their labor. The incongruence between the masculinity of a working class man and the demands of the service economy (Nixon 2009) exacerbates emotional pressures in customer-facing services, which can offer an explanation for angry outbursts and conflicts between drivers and customers.

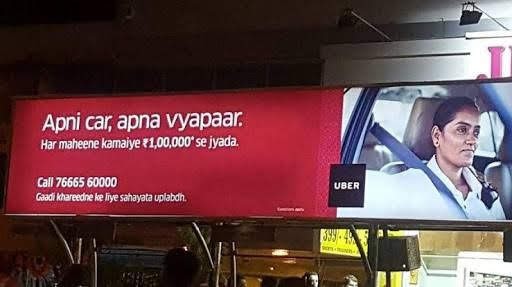

Uber’s ad on a billboard in Mumbai promises earnings of more than Rs. 1 lakh per month. Using a woman’s image illustrates the extent of their potential for transforming lives and livelihoods. Source: Drivers’ Union Telegram Group

While Uber and Ola claim that a large number of women drivers work on their platforms, actual experiences of passengers and the male drivers I spoke to, suggested otherwise. Ironically, mass driver-training programs are seen as a quick way to make low-skilled and migrant male workers employable in Indian cities while, despite public-private partnerships to train women, it has been impossible to retain women drivers due to stereotypical perceptions of gender and persistent social stigma.[3] This made the ridehailing passenger woman (upper middle class, affording professional) a stakeholder to design for, while female drivers (but all female workers) appeared as liability for platforms.

These narratives speak directly to the construction of insecurity and risk for women (Berrington and Jones 2002) on public transport systems as they highlight vulnerabilities due to public exposure of women’s bodies. Pandering to a moral panic standpoint and creating personalised or ‘inside’ safe spaces for women to manage risk (Green and Singleton 2006), these platforms can then be imagined as a boundary-setting exercise. Access to public spaces is encouraged but it is delimited by confining the woman’s body to a singular vehicle in the custody of the cab driver. Autonomy and access afforded by the platform manages to transform women—particularly upper class and upper caste women who can afford these services—into potential customers. Their agency is bounded though by tasking the driver to ferry her across the otherwise hostile cityscape filled with ‘unfriendly bodies’ (Phadke 2013). The production of the city’s gendered space goes hand in hand with the confinement/erasure of female bodies in the public space as they embody patriarchal norms even in a city as ‘progressive’ as Mumbai. As demonstrated by studies mapping the movement of women in the city (Ranade 2007), the spatio-temporal factors lend themselves to creating gendered bodies in order to keep patriarchal norms intact. These norms, as I argue in this post, are detrimental not just to women but also other marginalised sections of the urban population, in this case platform workers.

Terms of Safety

Male drivers’ social identities as lower class, lower caste individuals do not inspire confidence in the standards of safety boasted by these companies in the eyes of their predominantly upper caste and upper class customer base. Risk to female passengers is further exaggerated due to the closed space in which the service is provided, highlighting the proximity to a potential aggressor by way of these platforms. In specific situations wherein a female passenger is inebriated or is travelling alone at night, drivers report being extra cautious and helpful towards her. Many respondents proudly mention going out of their way to make sure women get home safely, for instance, prolonging waiting time or escorting them to the entrance of their residential buildings or involving the security guard at the gate.

However, there have also been cases wherein the driver has been under scrutiny either by an overly careful passenger or by the public. One driver reported being surrounded by a crowd at a traffic signal, only to realise that he was being suspected of foul play with the female passenger who had fallen asleep on the backseat of the car. In contrast to their western counterparts, the class differences between drivers and passengers in India exacerbate doubts, fears and insecurities in India which tend to take a caste-purity angle as well. The woman’s body undergoes an exchange of custody in these instances wherein she is deemed incapable of taking care of herself and requires external assistance. Imagining a deterrence effect of ridesharing services (Park et. al 2017) reinforces the logic of guardianship and protectionism for the woman. The risk of carrying her in the vehicle in these situations is borne by the cab driver, operating under a framework of overbearing protectiveness which holds him culpable for any misgivings, assumed or otherwise.

Cautionary listicles advise women to not take a cab alone at night, carrying pepper sprays/umbrellas as tools for self-defence, refrain from conversations with drivers or talk continuously on the phone, among other things. The onus of the woman’s safety is either on the individual herself or the driver who is ferrying her. Moreover, the driver is a likely assailant whom the woman should guard against as well. (Source)

Notions of safety and risk are embodied in everyday interactions in urban spaces and mediated by disparate infrastructures of knowledge across distinctions of caste, class and gender. These distinctions define constraints which govern social interactions between actors of these categories. Interactions between lower caste or Muslim men and upper caste/class women are circumscribed by what Tuan (1979) describes as ‘landscapes of fear’. Be it the apprehensions about sharing a ride with a passenger of the opposite sex (Sarriera et. al 2017) or reports of gang-rapes by cab drivers, the boundaries of social conduct are laid out clearly by constructing narratives of risk and safety. The protection of the female body and her sexual safety is not her responsibility alone but that of the society as a whole. The so called preventive measures for rape and violence against women produce the dichotomies of frailty and strength (Campbell 2005) in so far as they project the woman as always at risk with the shadow of a potential assault always looming large.

When asked about interactions with women as customers or fellow drivers, drivers performed exaggerated respectability for women. The catch in these narratives however was that drivers justified and extended respect only to ‘good’ customers, where a ‘good’ woman was a certain kind of a moral actor.

Given the prevailing discontent with redressal mechanisms for workers on the platforms, it was not surprising to witness a group of drivers at the Uber Seva Kendra (help centre) in Mumbai, debating whether they should be accepting requests from any female customers at all. Drivers also had to attend mandatory training sessions for ‘good conduct’ with customers wherein they underwent behavioral correction and gender sensitisation lessons.[4] The gendering of the platform economy is baked into these instructions and trainings that reproduce male drivers as figures of safety and constant positive affect.

Gender, Safety, and Enterprise

In my fieldwork, I also came across a slew of ventures run by fleet owners and others that sought to service women passengers and employ women drivers exclusively. Claiming to fill in the gaps of inadequate vetting mechanisms in existing platforms, these alternate ventures purportedly smoothened out some anxieties by eliminating the risk of interacting with a man from different socio-economic strata. The premium charged by these companies was telling of the value of safety and affordability of these services for a large section of their intended audience, namely women with higher disposable incomes residing in metropolitan cities.

On the flipside, these enterprises encouraged women to break stereotypical perceptions about women drivers, also giving a nod to increasing and diversifying opportunities of employment for women. However, these ideas remained attractive only in principle and fizzled out sooner or later as most of these ventures did not succeed. A severe capital crunch due to unsustainable business models, limited funding options and lack of substantial supportive ecosystems for training and upkeep are possible reasons for failure.[5] Even so, the idea of a women-centric service continues to remain valuable because of the promise of safety which is produced through considerations of class, caste, gender and religion (Phadke 2005). Any alternative to avoid interaction with men from a lower class or caste background or from another religion (especially Hindu/Muslim in Mumbai) is welcome in a society which is deeply stratified and entrenched in caste-class systems of religion and economy alike.

Conclusion

The pervasiveness of the discourses of safety and risk in the ride hailing space became apparent to me during field research. Respondents indicated a heightened awareness of my gender, referring to me as “madam” and taking measures to ensure my safety. They advised me to use a separate phone to interact with drivers and moderated my interactions with drivers on the Telegram group (run by one of the Unions in Mumbai). Union representatives were also diligent in moderating the group to filter out abusive language as a token of respect for women. My apprehensions in interacting with drivers, most of whom were older men from a lower class/caste community, were also indicative of my social conditioning as an upper class and upper caste woman. Self-policing and boundary setting in both physical and virtual interactions, while necessary to some extent, were often rendered useless as the shifting of risks became apparent to me in my interactions with the drivers.

In this piece, I have tried to show how gendered norms govern the construction of safety and risk which in turn regulate social interactions. Limiting exposure in a personal cab as opposed to a public bus/train also heightens considerations of intimacy and proximity to a potential aggressor (often from a marginalised sociocultural background). Women-centric cab services mitigate this by promoting the image of the female driver who breaks social norms. However, these services dwindle till they completely disappear due to a capital crunch or insufficient infrastructural support. Patriarchal contexts reaffirm the woman as a risky object by highlighting narratives of vulnerabilities and insecurities in the ridehailing space. Besides the woman, the cab drivers are held accountable for bearing this risk and ensuring her sexual and physical safety. These patriarchal hierarchies of protectionism are sustained by platform workers’ affective labour which lubricate the wheels of the platform economy.

References

Berrington, E. and Jones, H., 2002. Reality vs. myth: Constructions of women’s insecurity. Feminist Media Studies, 2(3), pp.307-323.

Campbell, A., 2005. Keeping the ‘lady’ safe: The regulation of femininity through crime prevention literature. Critical Criminology, 13(2), pp.119-140.

Chopra, R., 2006. Invisible men: Masculinity, sexuality, and male domestic Labor. Men and Masculinities, 9(2), pp.152-167.

Green, E. and Singleton, C., 2006. Risky bodies at leisure: Young women negotiating space and place. Sociology, 40(5), pp.853-871.

Nixon, D., 2009. I Can’t Put a Smiley Face On’: Working‐Class Masculinity, Emotional Labour and Service Work in the ‘New Economy. Gender, Work & Organization, 16(3), pp.300-322.

Park, J., Kim, J., Pang, M.S. and Lee, B., 2017. Offender or guardian? An empirical analysis of ride-sharing and sexual assault. An Empirical Analysis of Ride-Sharing and Sexual Assault (April 10, 2017). KAIST College of Business Working Paper Series, (2017-006), pp.18-010.

Phadke, S., 2005. ‘You Can Be Lonely in a Crowd’ The Production of Safety in Mumbai. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 12(1), pp.41-62.

Phadke, S., 2007. Dangerous liaisons: Women and men: Risk and reputation in Mumbai. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.1510-1518.

Phadke, S., 2013. Unfriendly bodies, hostile cities: Reflections on loitering and gendered public space. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.50-59.

Ranade, S., 2007. The way she moves: Mapping the everyday production of gender-space. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.1519-1526.

Raval, N. and Dourish, P., 2016, February. Standing out from the crowd: Emotional labor, body labor, and temporal labor in ridesharing. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 97-107). ACM.

Sarriera, J.M., Álvarez, G.E., Blynn, K., Alesbury, A., Scully, T. and Zhao, J., 2017. To share or not to share: Investigating the social aspects of dynamic ridesharing. Transportation Research Record, 2605(1), pp.109-117.

Tuan, Y.F., 2013. Landscapes of fear. U of Minnesota Press.