Reflections on the November 2015 Paris attacks from afar

I can’t recall the last time I heard “La Marseillaise” [1] as often as I have in the past few weeks. This is never a great moment for me. As for many fellow French citizens, the vindictive and blood calling lyrics of our national anthem have always triggered a feeling somewhere between discomfort and straightforward rejection.[2] Things were not different on that Sunday morning, November 15, 2015. Like many others—Francophiles or not, Francophone or not, or French or not—I was struggling to find words to explain what happened in Paris on the night of Friday the 13th to my five and seven year old kids. I was thinking our family could later join the crowd gathering in front of the San Francisco City Hall to grieve collectively, which was important as we felt so far from friends and relatives, and powerless. But first I wanted to make sure that my kids’ first encounter with the piece would not be traumatizing as the news of events.[3] Indeed, as people around the world in an act of support and friendship were singing this patriotic march, as they were giving life to lyrics from—what seems like—another time, French and American airstrikes on ISIS headquarters in Raqqa, Syria [4] had already started and the word “war” was on everybody’s lips, with incredulity and sideration but also determination.[5]

Following the multiple Paris attacks in the lively and popular 10th and 11th Paris arrondissements on November 13, 2015, I want to reflect on the complexity of witnessing from a distance, and engaging with, catastrophic events, disasters or, in this case, terrorist attacks. Whether we choose to pay attention or not, looking at, and participating in, the social construction of these events, has become part of our (almost) everyday lives. For those of us with computers, smartphones and social media accounts, looking at the unfolding of catastrophic events on our screens has become a routine of our modern life. But the way in which we engage with a crisis, a disaster, or a catastrophic event in social media frames the understanding of it for some time. Building on Susan Sontag and Virginia Woolf’s asynchronous discussion, I also want to reflect on questions of attachment and othering that emerged from this first moment of public definition. Along the way, I will also discuss the concept of resilience from an STS perspective, which has been used by journalists and politicians in the public debate as a performative concept (“we will be resilient”), within hours of the attacks.

Crises experienced through social media

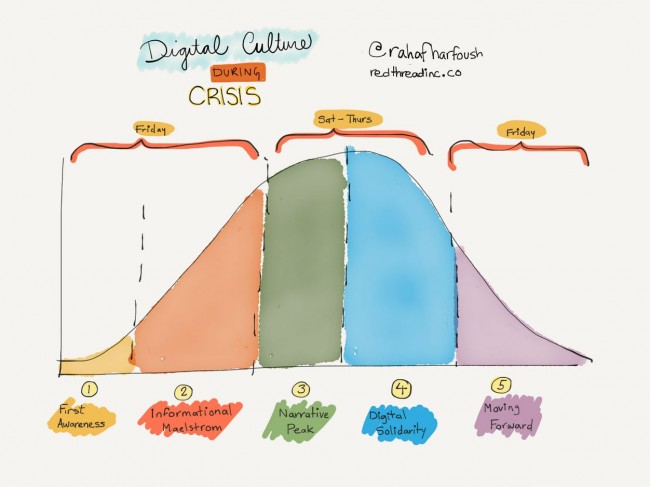

Rahaf Harfoush, a digital anthropologist, has very well described the phenomenon of our digital moving interest during a crisis.

Image: The five stages of digital culture during a crisis, by Rahaf Harfoush.

Often moving faster that information on cable TV (at least until the first crews get on the spot), the details of the events are leaked through tweets and posts on feeds that later display news about loved ones, connections and “friends.” Social media are changing the way we relate to disaster: as we feel more connected, we may feel more concerned, depending on what matters for us (a place, a type of event, a category of person, a political context). Social media gave us the opportunity to engage around the narrative that will be deployed slowly, materialized, and historicized. In the case of the Paris attacks, things were no different.

As a scholar working on risk and disaster for years, a French expatriate in a US university, a former resident of the 11th arrondissement in Paris, and a sister and friend of many current residents of the 10th and 11th arrondissements, the Paris attacks hit me just between the known and the felt, in a place where for hours after, I was drifting away, finding only bits of comfort in other distressed faces, haggard gaze of friends looking from a distance at a tragedy we could barely imagine. On Friday October 13th, I was at the annual meeting of the Society for Social Studies of Science (4S), in Denver, Colorado, and had just finished giving a presentation on resilience. Yes, resilience. That what I what I have been thinking about in recent years: vulnerability, disasters, trauma, reconstruction, resilience, etc. For people studying (natural or unnatural; mostly both) risk and disaster, like I do, the concept of resilience has become something between a new buzz word and operative concept, last on a long list of practitioners and researchers who have been trying to think—for decades now—about how we could understand, mitigate, prepare for and respond to disasters that, whether we like it or not, never fail to happen, sometime, somewhere, yet always surprise us.

The Paris attacks have been for me one of these moments of unexpected collapse, when distance is erased, sensemaking is so hard, and you are submerged in emotion and a great sense of absurdity. Around 4:00pm, Christine, a French woman that I had met and befriended only hours before, rushed to me from across the conference hall lobby with a tormented face, asking: “…attacks in Paris, have you heard?” “What…????” That Friday, sitting on chair of a hotel in Denver, struggling with a terrible WiFi connection, there I was, like millions of other people, with the help of my friend and colleague Laura (because I could not remember how to use my own computer), looking at Twitter, following the news. I knew that what I was living in that moment was an echo of what many of my Japanese friends and colleagues at the same conference had experienced during the Tohoku earthquake (but on a smaller scale), and what many others, looking at the news of a plane crash, an earthquake, a flood, a landslide, have been through. “Put yourself together, text, call, follow the news,” I told myself, trying to stay calm. This time, I—and my family, my friends—have been lucky: my sister was away for the weekend, my friend working on his dissertation (we’ll never praise enough the virtue of working long hours to our kids), others friends traveling for work But friends of friends and family were not and many were killed during the Bataclan attack. Later that day, we (current and former Parisians and friends of Paris) went to eat and get some drinks in bars where the music was loud enough to numb our pain.[6]

In the following days, as I traveled back to Berkeley, I kept looking at the news and France seemed like a very small place. For people of my generation—and even more so for younger ones—it is hard not to recognize ourselves in the list of victims that has slowly been released. A very young woman coming from Brittany not far from where I grew up, a guy living in the same location I once did, a woman slightly younger than I who graduated from the same program, only two years apart, another guy working at my friend’s company, a geographer working on urban gentrification teaching in the university where I also defended a PhD in geography, etc. The list goes on.

People who were killed last Friday were the cool kids, lefty middle class young people with (often) a college degree, equivalents of the American “hipster.” Not rich, necessarily, but fond of culture, attached to a certain idea of social diversity, engaged with the world. They were the one we called—with sympathy and sometimes disdain—the Bobos, for the Bourgeoisie Boehme.[7] If some of their life echoed my own life trajectory, they were all rooted in the multiplicity of life experiences of a the X and Y generations, the beauty of what big cities can offer to invent, re-invent, and become one’s self. People who died on that Friday were coming from everywhere; they were everybody, offering—beyond the grave they did not even reach—a mirror of both the diversity of the population, but also, and mainly its connection, its closeness. Wherever they were coming from, who ever they were, they were us, they were like us.

Drawing from French Artist Robabée that appeared on my Facebook wall on November 15, 2015: “It was not you, not me. But it, still, it was us.” (Reproduced with permission.)

For a while, social media amplified this feeling of empathy. But talking to my friends and family I could not stop thinking about Sontag’s warning: “No ‘we’ should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain” (Sontag 2004 [1977]:8), she wrote in her essay on photography in 1977, echoing a debate between Virginia Woolf and a London lawyer on the roots of the Second World War (Woolf 1963). Sontag has been warning us about the excess of the hyper-mediatization:

Citizens of modernity, consumers of violence as spectacle, adepts of proximity without risk, are schooled to be cynical about the possibility of sincerity. Some people will do anything to keep themselves from being moved. How much easier, from one’s chair, far from danger, to claim the position of superiority. (Sontag 2004[1977]:86)

In the first hours after the events, I found the #porteouverte hashtag, or any variation of the #prayforparis one, on Twitter. On Facebook, I found the Safety Check [8], a letter of love [9] from a young widower, and a lot of jokes, good and bad, but mostly good [10]. I also found a some bravado (“meme pas peur”[11]) and a lot of determination, to keep doing whatever people were doing before, lengthy and detailed descriptions of Parisians’ love for love, life, alcohol, sex, food, music, and culture; calls for outrage (e.g., Stéphane Hessel’s essay) and for peace. Following a concept they have learned to cherish lately, the Parisians and French were talking about their attachment to their lifestyle, #TousauBistrot.

Attachment and othering

What we are attached to….? As Bruno Latour points out:

It is no longer a question of opposing attachment and detachment, but instead of good and poor attachment, then there is only one way of deciding the quality of these ties: to inquire of what they consist, what they do how one is affected by them. (Latour & Stark 1999:22)

The concept makes visible individual “active passion,” “this form of ‘attachment’ which we attempt to describe as that which allows the subject to emerge—never alone, never a pristine individual, rather always entangled with and generously gifted by a collective, by objects, techniques, constraints” (Gomart & Hennion 1999). What I wanted to share during my 4S talk is that, as you understand when working with the concept of attachment, resilience is never given; it is a slow process that can succeed or fail. Despite the moral imperative that seems to proclaim overuse of the concept, despite its polyphony, resilience cannot be declared, or imposed, or even suggested. Rather resilience is a process, both individual and collective, a co-construction that needs to be grounded and which varies depending on the pre-existing situations. In this talk, I wanted to talk about trauma, the wound that never heals, this gaping hole that nothing seems able to fill. Like a Paris terrace where people were killed celebrating a birthday party, or a concert hall where people died in the dark.

Social media have certainly changed the mode of engagement around disasters and catastrophe, but can they help build more complex processes? What collective will emerge from the Paris attacks? Like those in Beirut, Lebanon on November 13 or in Nigeria on the 19th, the Paris attacks were a traumatic event for many of us, beyond borders and categories. By November 17th, my Facebook page displayed some of that (like the extraordinary work of my friend Philippe Rekacewicz on mapping the International Jihadist), as well as some reflective thinking from users of social media are starting to question their own practices and the motives of those who provide for the tools they use. Why did Facebook only activate the safety check during the Paris attack, asked Lebanese blogger Joey Ayoub? Is changing your profile with a French flag helping Facebook test adoption practices? What is the role of the different platforms in helping terrorists get organized? Can we really be cynical about it? [12] How far can solidarity—on social media and in the streets of large metropolitan areas—be extended to others victim of terrorist attacks? Who is we when the other become suspect, in Europe and in the US? Who is “we” when we sing La Marseillaise and paint our Facebook profile in blue, white, and red?

Walking in Paris’ street few days later a journalist noted that, in the aftermath of the attacks, “keyboard activists rapidly got activated: messages of solidarity and ‘resistance,’ French flag overlaying Facebook profile pictures, flights of poetry to commemorate the victims…. But in the streets, no one. For three days, many Parisian areas were abandoned to a deadly atmosphere” (Lanneau 2015) [13]. Only few day after the events, and despite praise for resilience and unity in media, and despite the bravado, the definition of “we” that congealed around low-hanging symbolic fruit (our terraces, our cigarettes, our drinks, our concerts, our free spirit) seems to be crumbling already, letting more complex political and emotional questions come flooding back, as well as—for a large part of the population—fear for the future. “After Charlie Hebdo, a woman called me ‘dirty Arab.’ It’s November 16th and I have been already insulted twice, and some looks are more hurtful than words,” [14] recalled a young woman (Lanneau 2015). As I was finishing this text, the terrorist suspected to have organized the attack was killed by the special police force in the suburb of Saint Denis.

As questions continue to emerge, and as the Climate Conference happening this week in Paris reminds us: it is about time to think about “what we care about” (Hache 2011).

Resilience is a co-construction—as much as politics is.

[Update: I learned while writing this, on November 19, that Alice, circus artist, dancer, and great soul, as well her brother Aristide, a rugby player, were hit at the Bataclan. Alice received one (several?) bullet(s) in the arm; Aristide was hit in the lungs and leg. They are both still being hospitalized.]

Endnotes

[1] The French national hymn, written by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle following the declaration of war with Austria in 1792.

[2] For the reggae version, see Serge Gainsbourg. Gainsbourg wanted people to dance to the Marseillaise.

[3] I should not have worried that much, family life being what it is; we never made it to the gathering….

[4] For more about the Islamic State Syrian headquarters, see Vice’s documentary by Medyan Dairieh.

[5] This answer of course very questionable. Many have been warning against the dangers of a rhetoric of war, among them for instance Latour and Zizek. The Verso blog has also gathered a collection essays from their authors.

[6] Thank you Kyoko, Reiko and Paul. Scott K., if you are reading this, I know I forgot to pay my drink when I left that night. Apologies. I owe you one….

[7] The contested term comes from David Brooks 2000 book Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There. Brooks defines the Bobos as “highly educated folk who have one foot in the bohemian world of creativity and another foot in the bourgeois realm of ambition and worldly success” (Voight 2010). As a French sociologist pointed out: “In sociological terms you are talking about the new middle class—journalistically labelled ‘bourgeois bohemian’ not because there is anything remotely bohemian about them but to mark them from off the traditional haute bourgeoisie. There are more and more of them; they are growing all the time; they are less and less uniform; and as they get richer it is far from certain that they will stay left-wing” (Merle in Burke 2008).

As French Humorist and guest of the satirical radio show “Si tu ecoutes j’annule tout,” Frederic Formet was singing recently “Allo maman, je suis bobo:”

Ouais on est a Paris, a la pointe de tout (Yep we are in Paris, cutting edge of everything)

On est petit genis, la gueule en biais c’est nous (We are little genius, and with attitude)

Je connais un bistrot, super sympa t’inquiete (I know a bar, very cool no worries)

Le café 5 euros, six avec une sucrette (Coffee for 5 euros, 6 with sugar)

It’s important to note that the 10th and 11th arrondissements present more social diversity and density than other arrondissements and have kept something of the cheap ’n’ chic spirit rather than Gauche caviar (Caviar left). The 11th arrondissement remains the most densely populated in Paris with 41,536 residents per km2 (source Wikipedia). According to 2006 data from National Institute of Statistical and Economical Studies, aggregated by the website Drmiki.fr, the average annual income in the arrondissement is above 30,000 Euros, more than 50% of the population is single (source: Drmiki.fr), and more than 25% of the population was born outside metropolitan France (source: Wikipedia).

[8] Since the Haitian earthquake, connections were made possible across the globe helping in the relief effort, from collecting data and gathering first aid supplies to locating individuals, because of the physical mobilization of individuals and the use of social media tools. Developing tools for disaster has been ongoing for a long time. The Facebook Safety Check was first installed during the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

[9] “Vous n’aurez pas ma haine” By Antoine Lieris. For English version see here.

[10] Or at least they seem so at the time…. Like this one: “Never doubt the courage of the French. They were the ones who discovered that snails are edible,” Doug Larson, undated; appeared on my Facebook Wall on 11/17/2015.

[11] “Meme pas peur!” is what French kids say when confronted to a daunting situation. The bravest would have a look of defiance and turn around, others look at you with big eyes, somehow reassured that nothing bad happened to them.

[12] I don’t want to mention here the Bad and the Ugly…. For more of that, see here.

[13] “Le militantisme de clavier s’est rapidement activé : messages de solidarité et de « résistance», incrustation du drapeau tricolore sur Facebook, envolées lyriques en hommage aux victimes… Mais dans les rues, personne. Durant trois jours, de nombreux quartiers parisiens ont été abandonnés à une ambiance moralement mortifère” (Lanneau 2015).

[14] “Après Charlie Hebdo, une dame m’a traité “sale Arabe”. On est le 16 novembre et je me suis déjà faite insulter deux fois et certains regards sont bien plus blessants que les paroles.” (Lanneau 2015)

References

Burke, J. (2008). French elite declare the Bobo extinct. Retrieved February 12, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/jun/01/france

Gomart, E., & Hennion, A. (1999). A Sociology of Attachment: Music Amateurs, Drug Users. In J. Law & J. Hassard (Eds.), Actor Network Theory and After (pp. 1–28). Wiley-Blackwell.

Hache, E. (2011). Ce à quoi nous tenons. Propositions pour une écologie pragmatique (Les Empêcheurs de penser en rond). La Decouverte.

Lanneau, T. (2015). Un café entre copains dans un 25m2, plutôt qu’en terrasse. Retrieved from http://bondyblog.liberation.fr/201511182328/un-cafe-entre-copains-dans-un-25m2-plutot-quen-terrasse/

Latour, B., & Girard Stark, M. (1999). Factures/Fractures: From the Concept of Network to the Concept of Attachment. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 36 (Autumn), 20–31.

Harfoush, R. (2015). Paris Under Attack: Digital Culture in Times of Crisis.

Sontag, S. (2004). Regarding the pain of others. Picador.

Voight, R. (2010). In France, a New Class Reinvents the Good Life : “Bobo” Style Has It Both Ways. Retrieved February 12, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/14/news/14iht-rbobo.t.html

Woolf, V. (1963). Three Guineas. Harvest Books.

1 Trackback